Introduction and summary

Wealth—the measure of an individual’s or family’s financial net worth—provides all sorts of opportunities for American families. Wealth makes it easier for people to seamlessly transition between jobs, move to new neighborhoods, and respond in emergency situations. It allows parents to pay for or help pay for their children’s education and enables workers to build economic sustainability in retirement. Importantly, it is the most complete measure of a family’s future economic well-being. After all, families rely on their wealth to pay their bills if their regular income disappears during an unemployment spell or after retiring, for instance.

Unfortunately, wealth in this country is unequally distributed by race—and particularly between white and black1 households.2 African American families have a fraction of the wealth of white families, leaving them more economically insecure and with far fewer opportunities for economic mobility. As this report documents, even after considering positive factors such as increased education levels, African Americans have less wealth than whites. Less wealth translates into fewer opportunities for upward mobility and is compounded by lower income levels and fewer chances to build wealth or pass accumulated wealth down to future generations.

Several key factors exacerbate this vicious cycle of wealth inequality. Black households, for example, have far less access to tax-advantaged forms of savings, due in part to a long history of employment discrimination and other discriminatory practices. A well-documented history of mortgage market discrimination means that blacks are significantly less likely to be homeowners than whites,3 which means they have less access to the savings and tax benefits that come with owning a home. Persistent labor market discrimination and segregation also force blacks into fewer and less advantageous employment opportunities than their white counterparts.4 Thus, African Americans have less access to stable jobs, good wages, and retirement benefits at work5— all key drivers by which American families gain access to savings. Moreover, under the current tax code, families with higher incomes receive increased tax incentives associated with both housing and retirement savings.6 Because African Americans tend to have lower incomes, they inevitably receive fewer tax benefits—even if they are homeowners or have retirement savings accounts. The bottom line is that persistent housing and labor market discrimination and segregation worsen the damaging cycle of wealth inequality.

See also

While this report focuses on wealth disparities between black and white households, it is important to note that Latino and certain Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) household wealth falls far below their white counterparts’ as well. Indeed, Hispanic families have only slightly more wealth than black families. In 2016, the median wealth for black and Hispanic families was $17,600 and $20,700, respectively, compared with7 white families’ median wealth of $171,000. The disparity between white and AAPI wealth is often overlooked because, collectively, their average and median wealth is comparable to whites. There is, however, significant wealth inequality among AAPI households.8 This report offers solutions to address the distinct issues that exacerbate the black-white wealth gap.

$17,600

Median wealth of black families in 2016

$20,700

Median wealth of Hispanic families in 2016

$171,000

Median wealth of white families in 2016

Exactly how bad is the wealth gap between blacks and whites? According to 2016 Federal Reserve data highlighted throughout this report, there are several key drivers perpetuating the considerable wealth gap between white and black Americans:

- African Americans own approximately one-tenth of the wealth of white Americans. In 2016, the median wealth for nonretired black households 25 years old and older was less than one-tenth that of similarly situated white households.9

- The black-white wealth gap has not recovered from the Great Recession. In 2007, immediately before the Great Recession, the median wealth of blacks was nearly 14 percent that of whites. Although black wealth increased at a faster rate than white wealth in 2016, blacks still owned less than 10 percent of whites’ wealth at the median.10

- Black households have fewer and are in greater need of personal savings than their white counterparts. For a variety of reasons, blacks are more likely to experience negative income shocks but are less likely to have access to emergency savings. As a consequence, blacks are more likely to fall behind on their bills and go into debt during times of emergency.

- African Americans face systematic challenges in narrowing the wealth gap with whites. The wealth gap persists regardless of households’ education, marital status, age, or income. For instance, the median wealth for black households with a college degree equaled about 70 percent of the median wealth for white households without a college degree. The gap worsens as households grow older. In 2016, blacks between 50 and 65 years old and near retirement had only about 10 percent of the wealth of whites in the same age group. This is down from the approximately 24-percent gap in 1998, when the same groups of people were between 32 and 47 years old.

- African Americans have fewer assets than whites and are less likely to be homeowners, to own their own business, and to have a retirement account. The most recent data available, from 2016, show that when blacks owned such assets, they were worth significantly less than assets owned by whites.

- Black households have more costly debt. In 2016, blacks with debt typically owed $35,560—less than 40 percent of the $93,000 in debt owed by whites. However, because blacks owed larger amounts of high-interest debt—such as installment credit and student and car loans—the debt they typically owed was more expensive. For example, blacks carry larger credit card balances than whites.

The persistent racial wealth gap leaves African Americans in an economically precarious situation and creates a vicious cycle of economic struggle. The lack of sufficient wealth means blacks are less economically mobile and therefore unable to grow their wealth over time. Policy levers such as improved access to higher education alone, while important, will not be enough to create equal opportunity in terms of wealth-building for all. Only broad and persistent policy attention to wealth creation can address this glaring inequity.

African American wealth and its accumulation

Wealth—an individual’s or family’s financial net worth—can function as a generational stepping stone that older generations pass on and future generations benefit from and build over time. Throughout most of American history, however, this essential stepping stone was not, for all intents and purposes, available to African Americans. For blacks, the American experience began with slavery, which allowed whites to profit off of the bodies and blood of enslaved people, who by rule of law were unable to live freely, let alone build wealth to pass along to future generations. More than one and a half centuries since slavery’s abolition, America has yet to fully reckon with how to atone for this original sin. The disparities that exist between blacks and whites today can be traced back to public policies both implicit and explicit: From slavery to Jim Crow, from redlining to school segregation, and from mass incarceration to environmental racism, policies have consistently impeded or inhibited African Americans from having access to opportunities to realize the American dream. Direct action must be taken to change an American system built on suppression, oppression, and the concentration of power and wealth.

From slavery to Jim Crow, from redlining to school segregation, and from mass incarceration to environmental racism, policies have consistently impeded or inhibited African Americans from having access to opportunities to realize the American dream.

Decade after decade, black Americans have struggled to keep pace with their white counterparts and—despite momentous effort—continuously find themselves several steps behind. The data are clear: Even when African Americans pursue higher education, purchase a home, or secure a good job, they still lag behind their white counterparts in terms of wealth. Moreover, the disparities between white and black Americans can nearly always be traced back to policies that either implicitly or explicitly discriminate against black Americans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, black mothers and children die at disproportionately higher rates than their white counterparts, regardless of their income levels.11 Researchers have suggested that racism—which has produced segregated neighborhoods with fewer hospitals, higher rates of chronic illnesses, and unequal access to health care—is the main culprit.12

For most African Americans, the American promise that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about in his famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, whereby “all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,”13 has not been fully realized. Indeed, more than half a century later, it is clear that America has defaulted on its promises to citizens of color. What most people forget about that speech is that Dr. King also spoke about the “fierce urgency of now” and how now is not the time “to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.” Fifty years after his assassination, we are in a similar moment. Bold action is required.

The theory of targeted universalism developed by John A. Powell at the Haas Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, focuses on executing targeted strategies to meet universal goals.14 This nation can no longer treat differently situated persons similarly in its policy responses. The theory states that universal approaches alone will not bring change and will, in many cases, exacerbate the current divide. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, for example, used federal dollars to build highways across the country and created the suburbs.15 This act, while deemed universally beneficial, further entrenched racially isolated urban residents from newly formed, predominately white suburbs.16 Similarly, following World War II, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) helped millions of American veterans purchase homes and obtain an education.17 These policies were designed to be race- and gender-neutral but in practice disproportionately helped white men.18 Moreover, these policies were executed by states, many of which dispersed loans more often to white men, resulting in fewer loans for women and black veterans.19 In addition, black veterans’ educational benefits were only available for a limited number of black colleges—in many cases, the only institutions of higher education open to blacks—which led to overcrowding at those schools.20

When considering policy recommendations to close the racial wealth gap, one thing must be acknowledged: Poor blacks and poor whites are not similarly situated because whites have been and continue to be treated more favorably than blacks by government institutions. Targeted universalism provides a framework for closing the racial wealth gap because, as Powell notes, it is “inclusive of the needs of both the dominant and the marginal groups but pays particular attention to the situation of the marginal group.”21 Furthermore, it is essential that we accept full responsibility for our nation’s history and the systems in place if the goal is to move forward and close the wealth gap between white and black Americans. Going forward, policymakers should use a targeted universalism framework to design and advance policies that ensure equity.

Comparing wealth inequality with income inequality

Much has been made recently about rising income inequality and the concentration of income among America’s richest households. While income inequality certainly remains a pressing policy issue, wealth inequality is worse and deserving of closer attention.

Income and wealth are different and require unique considerations. Income, on the one hand, includes earnings from work, Social Security benefits, and pension benefits, as well as interest and dividends that households use to meet their current spending needs. Wealth, on the other hand, consists of any form of savings, including the value of one’s houses and cars, minus one’s debt. In other words, wealth is the amount of money that people can spend in the future. The combination of income and wealth tells a lot about a household’s current and future economic security. This report focuses solely on wealth, which is substantially more concentrated among America’s richest households than income, and thus leaves many households—especially black households—economically insecure.

Wealth is more concentrated than income

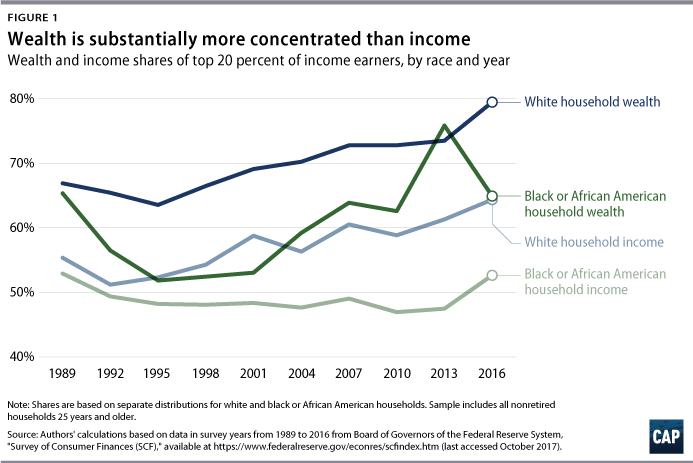

Wealth is a critical tool for families to finance and achieve economic mobility. It allows individuals to change jobs, pursue an education, and start their own business. It also helps people pay their bills during an economic emergency such as a layoff or unforeseen health emergency. Yet wealth is heavily and increasingly concentrated among the richest households. Figure 1 shows the wealth and income shares of the top 20 percent of income earners among blacks and whites.

Several important points are worth noting.22 As mentioned previously, wealth is more concentrated than income. This means that many households have little or no cash saved to use during an emergency. For example, in 2016, the richest 20 percent of blacks owned 64.9 percent of all black wealth but only received 52.6 percent of all black income. Moreover, since 1995, wealth has become increasingly concentrated for both blacks and whites. In the 1990s, the richest 20 percent of blacks owned 51.5 percent of all black wealth compared with 64.9 percent in 2016. The difference between wealth and income concentration is about the same for blacks and whites. The ratio of the share of wealth received by the richest 20 percent of blacks to the share of income they received is 123.3 percent. This compares to a proportion of 123.5 percent for the richest 20 percent of whites.

Wealth is more concentrated than income, and its concentration has grown for both blacks and whites. Even with this concentration, vulnerable subgroups of whites with little wealth still tend to fare much better than economically more secure subgroups of African Americans. That is, the concentration of wealth matters both within groups and across groups, as most blacks increasingly lose out in both directions. As a result, most blacks have few protections in the case of a financial emergency and have limited means for upward mobility.

The persistent and widening racial wealth gap

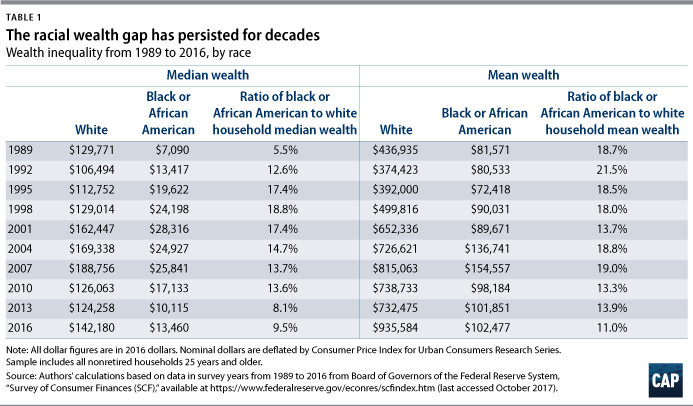

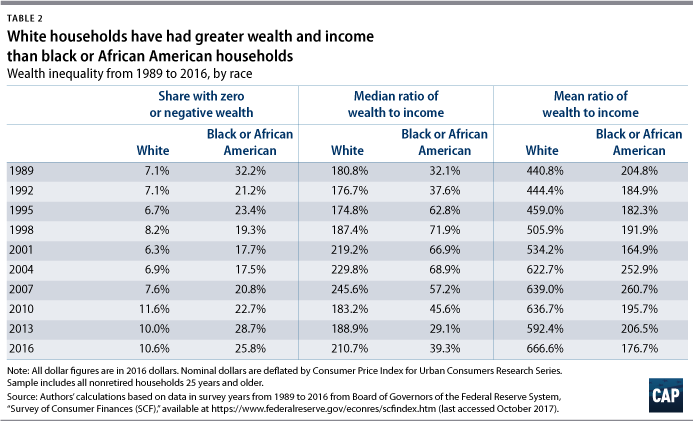

African Americans systematically have less wealth than whites. Tables 1 and 2 summarize several wealth measures by race including median wealth, average wealth, and the share of households with no or negative wealth.23 The median black wealth in 2016 amounted to $13,460—less than 10 percent of the $142,180 median white wealth. (see Table 1) The average black wealth was 11 percent that of whites, and slightly more than one-quarter of blacks had no or negative wealth, compared with only a little more than 10 percent of whites. (see Table 2)

In the wake of the Great Recession, which lasted from 2007 through 2009, America has seen its black-white wealth gap increase sharply.

The black-white wealth gap has persisted for decades. As shown in Table 1, the median wealth for black nonretirees over the age of 25 has never amounted to more than 19 percent of the median wealth of similarly situated whites since 1989. Additionally, the ratio of average black wealth to average white wealth never exceeded 21.6 percent in 1992. Roughly speaking, the best-case scenario for the past 30 years occurred when blacks had about one-sixth the median wealth of whites in 1998.

The black-white wealth gap has persisted for decades. As shown in Table 1, the median wealth for black nonretirees over the age of 25 has never amounted to more than 19 percent of the median wealth of similarly situated whites since 1989. Additionally, the ratio of average black wealth to average white wealth never exceeded 21.6 percent in 1992. Roughly speaking, the best-case scenario for the past 30 years occurred when blacks had about one-sixth the median wealth of whites in 1998.

But in the wake of the Great Recession, which lasted from 2007 through 2009, America has seen its black-white wealth gap increase sharply and move even farther away from that best-case scenario. In 2016, median black wealth stood at $13,460—about half of the median black wealth recorded just before the Great Recession. (see Table 1) At the same time, median white wealth was only one-quarter less than it was prior to the Great Recession, declining from $188,756 to $142,180. (see Table 1) The average black wealth in 2016 was still about one-third less than it was before the start of the Great Recession—$102,477 compared with $154,557. Over the same period, average white wealth grew by about 15 percent—from $815,063 in 2007 to $935,584 in 2016. (see Table 1) The Great Recession did greater damage to black wealth than it did to white wealth, widening the racial wealth gap even further over the past decade.

A simple calculation puts the persistent and policy-driven black-white wealth gap into perspective. Consider that the racial wealth gap—measured as the ratio of median black wealth to median white wealth—slightly narrowed from 2013 to 2016. (see Table 1) If this pattern continued over time and with no major policy changes, it would take more than 20 years just to return to the racial wealth gap that existed in 1998. Moreover, it would take more than 200 years for median black wealth to equal median white wealth. Leaving wealth inequality to market forces would likely create a massive gulf in economic opportunity and security by race. That said, shrinking the black-white wealth gap in a meaningful way will undoubtedly require large, targeted policy interventions.

Black households are in greater need of wealth

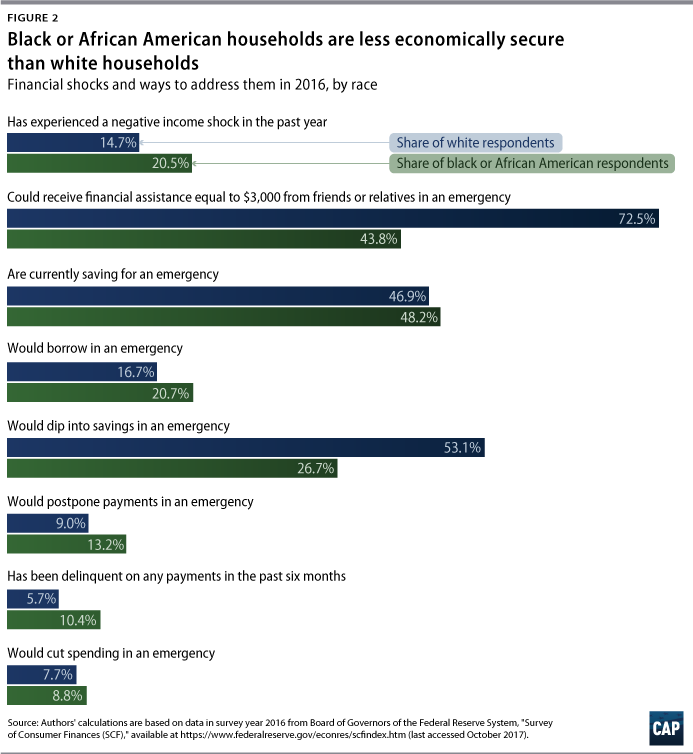

For a variety of reasons, African Americans are more vulnerable to economic insecurity and therefore are in greater need of wealth. This economic insecurity stems from the fact that blacks are more likely to be underpaid, less likely to have adequate savings, and less likely to have sufficient financial resources to respond to an emergency. For example, the primary worry for most families is often how to continue paying household bills when an emergency occurs. Saving for an unforeseen event was the single most important issue among both blacks and whites in 2016. Nearly half of all blacks said that they were saving for such events compared to 46.9 percent of whites. (see Figure 2) In comparison, saving for retirement was a distant second for both blacks and whites.24

Data on household financial distress highlights why families, especially black households, rank saving for short-term liquidity so high. More than five years after the Great Recession ended, in 2016, one-fifth of blacks reported an income shock—meaning their income was less than usual—compared with 14.7 percent of whites. (see Figure 2) Less than half of blacks could receive financial assistance from family or friends in an emergency, compared with almost three-quarters of whites. As a result, blacks were more likely to need to borrow, to postpone payments, and to cut back on spending in an emergency than whites. (see Figure 2) Not surprisingly, blacks are already about twice as likely as whites—10.4 percent to 5.7 percent, respectively—to be behind on bill payments, which reflects their more precarious financial situation. That is, blacks are more in need of short-term savings because of their day-to-day financial struggles. And as the data in the following sections show, blacks have significantly less wealth than whites. The combination of greater income volatility, fewer emergency savings, and less wealth for blacks than whites creates a highly insecure economic situation for many families.

African Americans face systematic obstacles in shrinking the wealth gap

The black-white wealth gap is a result of the institutionalized obstacles blacks face in building wealth. Take assets, for instance: The U.S. tax code prioritizes savings in certain assets over other savings. Retirement savings accounts such as 401(k) plans and individual retirement accounts (IRAs), as well as mortgage borrowing to finance a primary residence, receive preferential treatment under the tax code. Yet blacks are less likely to work in jobs that carry benefits such as retirement savings due to historical occupational segregation.25 Similarly, blacks are much less likely to become homeowners due to systematic housing and mortgage discrimination.26 These obstacles translate into fewer tax advantages and fewer chances to benefit from recent stock and housing market gains, resulting in significantly less wealth for black than for white Americans.

Racial differences also exist with respect to debt. Typically, blacks have more costly—or high-interest—debt, such as auto loans, student debt, and credit card debt, than whites.27 Blacks also pay more for installment loans, such as car loans, than whites.28 These patterns of having more costly debt in part reflect credit steering—when people of color are steered toward particularly costly forms of credit— and credit market discrimination—when people of color are more likely to be denied loan applications for less costly loans, as is often the case with mortgage loans.29

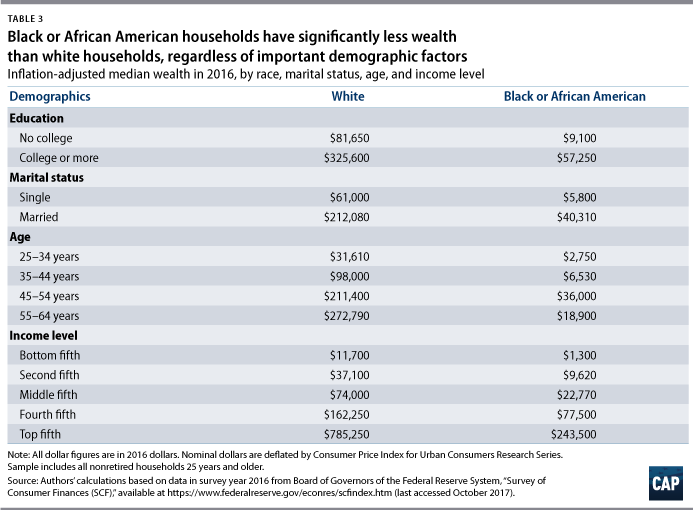

Blacks with at least a college degree still had about 30 percent less wealth than whites without a college degree—$57,250 compared with $81,650, respectively.

The black-white wealth gap reflects differences both in assets and in debt. And while higher education and increased income offer some benefits, they are insufficient to close the wealth gap.

Table 3 summarizes median wealth by race and several key demographics such as education, marital status, and income in 2016. The data reveal that blacks who have higher education levels, are married households, and obtain higher incomes still acquire significantly less wealth than whites who lack those qualifications. For instance, blacks with at least a college degree still had about 30 percent less wealth than whites without a college degree—$57,250 compared with $81,650, respectively.30 Similarly, the median wealth of married African Americans in 2016 amounted to only two-thirds of the median wealth of unmarried whites. The wealth gap also does not noticeably shrink with age. Blacks between the ages of 55 and 64, for instance, had a median wealth of $18,900—less than 7 percent of the median white wealth. This is similar to the ratio of median wealth for black and white households between the ages of 35 and 44 years—$6,530 to $98,000, respectively. Likewise, higher income does not close the wealth gap. Blacks in the top one-fifth of the income distribution still have less than one-third the wealth of whites in the same income distribution level.

Factors that are generally associated with rising wealth—education, marriage, education, and income—are unevenly distributed by race. Even when controlling for these factors, a massive wealth gap exists for all subgroups.

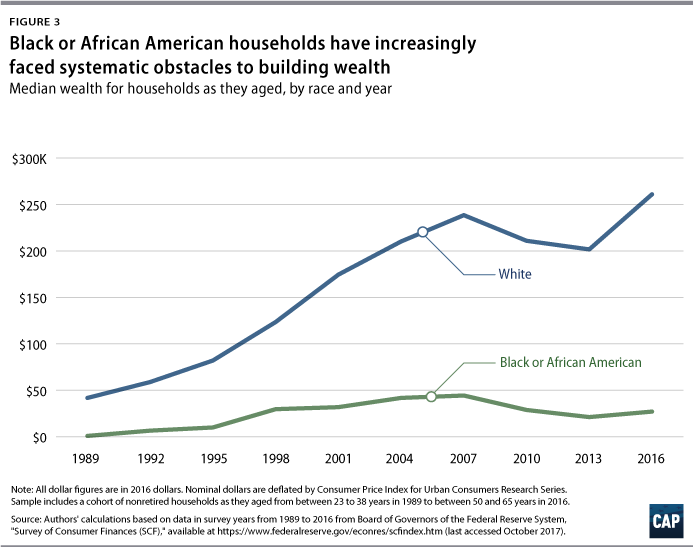

Figure 3 demonstrates that blacks face systematic obstacles in shrinking the racial wealth gap in a slightly different way. The data show the median inflation-adjusted wealth of households as they aged by looking at households in 1989—when they were between 23 and 38 years old—and comparing them with how they fared in in 2016—when they were between 50 and 65 years old. Both racial groups in this age cohort coincidentally should have benefited from greater homeownership, lower interest rates, and a rising stock market. At a minimum, the gap should not have widened as people aged. That is, however, exactly what happened. Blacks in this age group had 24 percent of white wealth in the same age group in 1992—the largest share over the past three decades. By 2016, this share dropped to only 10.4 percent. The widening gap can be attributed in part to the foreclosure crisis, which had a devastating effect on communities of color, who were disproportionately targeted for subprime loans. Indeed, black families lost 48 percent of their wealth during the financial crisis.31 In the intervening years, however, the wealth gap grew almost continuously, suggesting that it was not just an artifact of the Great Recession. That is, blacks have encountered mounting systematic obstacles—such as mortgage-market discrimination and labor market segmentation—that increased the wealth gap as they aged and neared retirement.

Black households have less access to critical savings vehicles

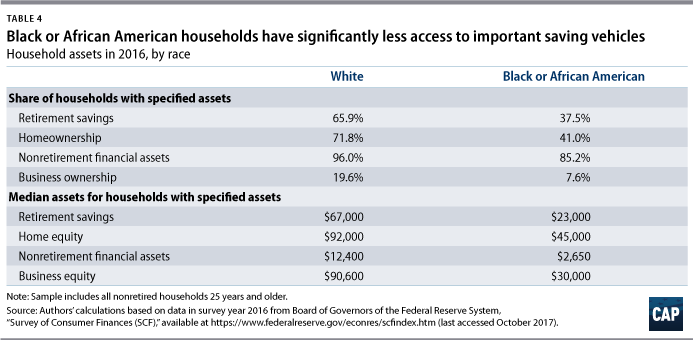

Much of the wealth gap can be traced to blacks having significantly less access to important savings vehicles—such as housing and retirement accounts—than their white counterparts. Table 4 summarizes the shares of blacks and whites with specific assets such as residential housing and retirement accounts, as well as the median amounts that both groups own in those categories. In 2016, only 41 percent of blacks owned their homes, compared with 71.8 percent of whites. Black homeowners also had less than half the home equity of white homeowners—$45,000 compared with $92,000, respectively.

The data in Table 4 show similar differences for retirement savings. Only 37.5 percent of nonretired blacks had retirement savings plans—401(k)s and IRAs—compared with 65.9 percent of whites. Blacks had a median balance in retirement savings that was approximately one-third that of whites—$23,000 compared with $67,000, respectively.

Further, blacks were less likely to obtain other nonretirement financial saving options—such as savings bonds and mutual funds—than was the case for whites. Most blacks and whites had some of these savings, but the median savings of blacks were just 21.4 percent of the median savings of whites—$2,650 compared with $12,400, respectively.

41%

Share of blacks who owned their homes in 2016

71.8%

Share of whites who owned their homes in 2016

Finally, the data show that in 2016, blacks were less than half as likely to own private business interests as whites. Their median business equity, when they did own a business, equaled one-third that of whites—$30,000 compared with $90,600.

Blacks thus have less access to savings and have built up fewer assets than whites, even when comparing for the same types of assets and regardless of the type of assets. The gaps in the likelihood of owning specific assets—such as retirement savings, a home, or a business—and in the median values of such assets are large. That is, the black-white wealth gap is in part a pervasive difference in asset ownership.

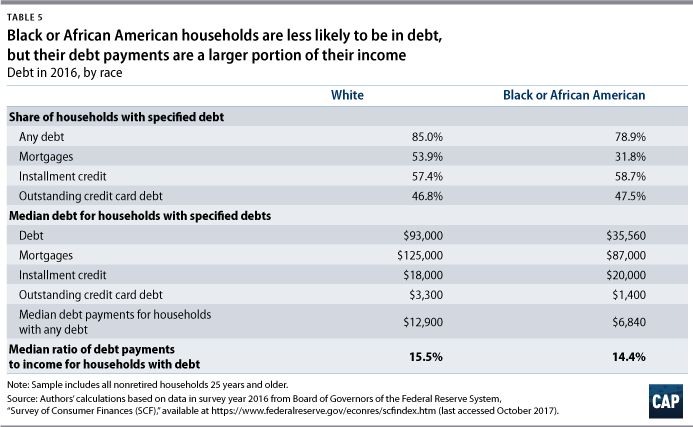

African Americans are burdened with more costly debt

On the other side of the ledger, debt tends to be more detrimental to blacks than for whites, largely because the types of debt they owe—such as car or student loans—are more costly. Despite blacks being slightly less likely to owe money than whites; only slightly more than three-quarters of blacks owed any debt, compared with 85 percent of whites. (see Table 5) Blacks’ debt payments, however, are relatively large compared with that debt. The total amount of debt that African Americans owed in 2016 was approximately one-third that of what whites owed. Yet, blacks typically had debt payments that were more than twice as costly as those as whites—$12,900 compared with $6,840, respectively. Relative to their incomes, blacks generally had debt payments that were almost as costly as those for whites—14.4 percent of their income compared with 15.5 percent of white households’ income.

More costly debt—such as car loans, student loans, and credit card debt—is the main driver for the discrepancy between outstanding debt and debt payments when comparing blacks to whites. Though federal student loans have generous repayment options, they are a more expensive type of debt than other instruments such as mortgages. Blacks are particularly less likely to owe money on a mortgage or home equity line of credit, which tend to be a comparatively less expensive way to borrow. Yet blacks are slightly more likely to owe installment loans such as car and student loans than whites. The amount blacks owe on such loans is also typically higher than what whites owe—$20,000 compared with $18,000. Moreover, blacks are more likely to carry a credit card balance than whites despite their balances being less than that of whites—$1,400 compared with $3,000. The higher costs of debt payments further impede blacks’ ability to build wealth and economic security for their families.

Income and employment are yet additional obstacles

Similar to the wealth gap, the income gap has worsened over time. According to a 2016 Economic Policy Institute report, the income gap between blacks and whites has grown since the 1970s.32 In 1979, for example, black men earned 22 percent less than white men; by 2015, black men earned 31 percent less.33 The report’s authors noted that in 1979, black women’s wages reached near-parity with white women’s wages, but that by 2015, the gap rose to 19 percent. The report also found that the gaps persist across women’s education levels and worsen for those with higher levels of educational attainment. In 1980, college-educated black women with more work experience actually earned slightly higher wages than college-educated white women with the same experience. By 2014, however, the gap had widened to 10 percent in white women’s favor. Similarly, while the gap between college-educated black and white men in 1980 was slightly less than 10 percent, it rose to nearly 20 percent by 2014.34 In 2017, researchers from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco similarly concluded that the black-white earnings gap is growing and that the growth can largely be attributed to so-called immeasurable factors.35

Furthermore, blacks are more likely to be unemployed than whites. In 2010, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, black unemployment swelled to 16 percent, while white unemployment topped out at slightly less than 9 percent.36 Even as black unemployment reached its lowest rate on record, it remains at roughly double the white unemployment rate.37 Recent analysis by the staff of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System shows substantial gaps in labor market outcomes between blacks and whites.38 Similar to the Federal Reserve Bank study, the Federal Reserve Board staff attribute this gap largely to unobservable factors. Put differently, the black-white gaps in unemployment, labor force participation, and employment-to-population ratio cannot be explained by measurable factors such as marital status, education, age, or geographic location.39

Both the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) and the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco reports suggest that the unobserved or unexplained factors that play a role in the black-white income and employment gap include employment discrimination, weak enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, or racial differences in unobserved skill levels—as opposed to measurable factors such as educational attainment or work experience.40 Moreover, a recent meta-analysis from researchers at Northwestern and Harvard universities and the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research found that rates of racial discrimination in hiring have changed little over time. The study’s authors found that on average, white applicants receive 36 percent more callbacks than black applicants with similar qualifications.41

There are several potential reasons why blacks experience higher rates of unemployment and earn lower wages than whites. As the EPI report notes, blacks contend with labor market discrimination, which is not easily measured. Black workers are also more sensitive to the business cycle and thus are more significantly impacted by negative economic shocks. Between 1996 and 2000, for example, as the economy neared full employment, the income and employment gaps between blacks and whites shrank.42 When the Great Recession hit in 2007-09, blacks were more negatively affected and struggled for a longer period of time to return to their prerecession wages and employment rates.43 In addition, black families have been disproportionately affected by the decline in union density. In 1983, 31.7 percent of black workers were union members; by 2015, that number declined to 14.2 percent.44 Moreover, broader wage stagnation has hit black workers harder.45

Finally, it is likely that disparities in employment may actually be underestimated because they do not account for the large number of blacks who have been negatively impacted by a criminal justice system that has aggressively and persistently targeted communities of color.46 A 2016 Washington Post analysis found that if incarcerated individuals were included in the official unemployment rate, the black male unemployment rate would spike from 11 percent—where it was at the time the article was published—to 19 percent.47 By comparison, factoring in the white male incarcerated population into the white unemployment numbers would raise the rate by less than 1.5 percentage points.48 Black men, for example, are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men—a result of policies that have either directly or indirectly promoted mass incarceration and overcriminalization in communities of color—meaning that they are more likely to experience barriers to employment as a result.49

Recommendations

Policymakers should use the equity framework of targeted universalism to deliver solutions in closing the black-white racial wealth gap. The following recommendations should be viewed through this lens and aim to address historical and systematic barriers to equality.

Build savings

The analysis in the earlier sections of this report reinforces how critical assets are to wealth building and to intergenerational wealth transmission. African Americans, however, face systemic barriers to acquiring, maintaining, and obtaining returns from assets such as housing, retirement and savings accounts, and business investments. It is therefore crucial to ensure that policies aimed at reducing the black-white wealth gap focus on African Americans gaining access to the type of wealth-building instruments that can help them build and transfer wealth over time.

Expand housing and homeownership among black families

Housing has always been and continues to be the main vehicle for families to build wealth. This is especially true for black families. Sixty-nine percent of blacks’ household wealth was derived from home equity, compared with 57 percent of whites in 2013.50 Unfortunately, America has a long history of housing discrimination that continues to impact black families today. Decades of public policies that have supported segregation and concentrations of high-poverty communities across the country have made it harder for black families to build wealth.

During the Great Depression, a two-tiered approach to housing policy emerged, which greatly impacted blacks’ residential mobility by pushing them into segregated communities. While the government promoted homeownership and suburbanization among whites, it further entrenched inequality in inner-cities through slum clearance and the construction of public housing—originally constructed as temporary middle-class housing and later a permanent housing solution for low-income people of color. In 1934, Congress passed the National Housing Act, which created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), to support mortgage lending. The FHA adopted the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s rating system—known as redlining—around certain areas deemed risky and therefore where lenders would not extend loans.51 Redlining forced black families into higher-rate loans—if they could get them in the first place—which required them to live in certain areas within the community and in many instances prevented them from acquiring a home at all. It wasn’t until 1968, with the passage of the Fair Housing Act, that redlining was made illegal.52 The FHA also recommended the use and application of racially restrictive covenants, which persisted even after they were eventually outlawed. Despite the illegalization of this process, the remnants of this practice in altered forms are still in place and active today.

Because wealth is often built over generations, the legacy of these policies has made it even more difficult for future generations of black households to participate in homeownership. Today, the disparity between white and black families who own homes is stark. Seventy-three percent of white families own a home compared with just 45 percent of black families.53 In addition, black families who do own homes are more likely to face barriers throughout the process. For example, black families are more likely to face predatory lending practices and to live in lower-income neighborhoods. According to a study conducted by Stanford University, when African Americans can purchase a home, they are more likely to be in low-income neighborhoods than their white middle- and low-income counterparts.54 As a result, the mean net housing wealth among white homeowners is $215,800 compared with $94,400 for black homeowners.55 Segregation still has a powerful impact on black families’ home values: Research shows that when a neighborhood becomes more than 10 percent black, home values decrease.56

Housing has always been and continues to be the main vehicle for families to build wealth. This is especially true for black families.

Not only is it harder for black families to purchase a home, but it is also less likely that they will receive a similar return on their investment. The median home equity amount for white homeowners in 2008 was $86,800, compared with only $50,000 for black homeowners.57 Home equity for black families represents more than half of their acquired wealth, whereas for white families it represents just 39 percent.58

While increasing homeownership rates can help narrow the wealth gap between blacks and whites, it alone will not close it completely. A 2015 Demos study estimated that closing the gap in homeownership rates between white and black families would cause the racial wealth gap to decrease by 31 percent. Their analysis further uncovered that making the returns of blacks’ homeownership equal to the returns white families see on their investment would further reduce the gap by 16 percent.59

Policies aimed at improving homeownership rates should focus on improving access to homeownership; lowering the cost of homeownership; and eliminating discriminatory practices and policies that prevent black families from seeing the same returns as white families.

Expand access to Community Development Financial Institutions

Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) are banks, credit unions, and other local financial institutions that support small businesses and affordable housing and provide other financial needs to distressed urban and rural communities that mainstream banks do not serve.60 The loans they deliver support efforts such as opening local businesses and financing for affordable housing, among other efforts—all of which support the broader community. CDFIs are critical to helping blacks purchase homes.

Support and protect intentional policy changes for fair housing

As the data in this report reflects, making policy changes to close the black-white wealth gap must be an intentional process. In 2015, the Obama administration finalized a new regulation aimed at clarifying and strengthening a key provision in the Fair Housing Act that requires the U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to “affirmatively further fair housing.”61 The rule requires any community receiving housing block grants from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to decrease residential segregation; eradicate racially or ethnically concentrated areas of poverty; reduce unequal access to community resources; and narrow gaps that result in disproportionate housing needs among vulnerable communities.62 The Obama administration required participating communities to demonstrate that they were pursuing these goals by submitting an Assessment of Fair Housing. Early this year, current HUD Secretary Ben Carson postponed the date by which jurisdictions are required to submit assessments to October 2020.63 Doing so places this rule, aimed at intentionally helping to improve housing desegregation efforts, at risk.

Ensure access to affordable rental housing

Saving for a down payment on a home is a challenge for most Americans, and doing so becomes increasingly challenging for families who do not have access to affordable rental housing options. Access to affordable rental housing not only helps families save for a down payment, but it also enables them to afford other daily essentials and to save for retirement without feeling strapped.64 Increasing the supply of affordable rental housing can help reduce costs for black renters and help them direct more of their income into savings and toward other essential expenses.65 To that end, the Center for American Progress has recommended expanding and better targeting the Low-Income Housing Tax Credits; creating a federal renters’ tax credit similar to the mortgage interest deduction for homeowners; eliminating exclusionary and restrictive zoning policies; increasing funding for housing vouchers; and preserving and revitalizing the affordable housing supply.66

Institute a comprehensive set of rules to govern land installment contracts

Land installment contracts are an alternative to traditional mortgage options. Despite allowing buyers to make direct payments to the seller over a set period of time, these transactions can be problematic. Once the full purchase price has been paid, sellers are supposed to turn over the title—but that does not always occur. This type of contract was used in the early 1900s by black Americans who were excluded from the traditional housing market.67 In the wake of the recent housing crisis, large private equity firms have been buying up foreclosed properties and targeting black borrowers again with land contract arrangements. To ensure that black borrowers are not once again defrauded by unscrupulous sellers, it is essential that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau provide a set of guidelines for states to protect borrowers.68 Such rules should include: the right to cure in situations of default; the recording of land contracts; the requirement for an independent appraisal; no liens on a property prior to entering into a purchase contract; and the establishment of an interest cap. 69

Improve access to retirement savings

Homeownership alone cannot be the only path to wealth-building for black families. The housing crisis triggered during the Great Recession had a significant impact on black wealth, in part because blacks were more likely to have their wealth tied up in home equity.70 African Americans therefore must also have access to different types of asset-building tools.

Slightly more than one-third of blacks have a retirement savings account, compared with nearly 70 percent of whites. The amount they have saved in those accounts is less than whites as well.71 This is in part because blacks are less likely to work in jobs that offer retirement plans. CAP has proposed establishing a National Savings Plan (NSP), which would operate similarly to the Thrift Savings Plan used by federal government employees and members of Congress.72 An NSP would offer access to an affordable retirement savings account for individuals who do not have access to a retirement plan through their workplace.73

Expand opportunities for entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship can be an avenue to wealth building, yet it often requires wealth that black families don’t have or access to capital that is difficult for black families to obtain.74 Policies aimed toward expanding access to capital—such as the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI), which was established in 2010 to provide loans to small businesses in the wake of the financial crisis when banks were hesitant to lend—can help.75 SSBCI allowed states to establish their own small-business programs with local economic conditions in mind. Importantly, the program required state SSBCI applicants to increase access to capital for underrepresented groups, including communities of color. The initiative was only authorized through 2017, and while the Obama administration proposed reauthorizing the program in its final budget,76 the Trump administration has not engaged in similar efforts. In 2017, President Donald Trump proposed eliminating the Economic Development Administration as well as the Minority Business Development Agency, which would certainly make it more difficult for African Americans to start small businesses.77 The loss of these programs would negatively impact African Americans’ ability to build and maintain wealth.

Reduce blacks’ debt load and the cost of their debt

Blacks are more likely to own costlier debt than whites. As data from the Survey of Consumer Finances show, blacks are also more likely to miss a payment, postpone a payment, or borrow in an emergency.78 Policies to reduce debt should focus on protecting consumers; improving access to low-cost financial institutions; and reducing the need to take on costly debt.

Protect the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was established in the wake of the 2007-08 financial crisis with a mission to protect consumers from fraud, discrimination, and abuse in the financial marketplace. Considering the disparate treatment blacks have received in the financial marketplace for decades, this agency is critical to protecting them from wealth-stripping products and policies. The agency has targeted discriminatory lending in the auto loan, home loan, and credit card industries. It has also targeted payday lending companies—which are disproportionately located in predominately black communities—and defended vulnerable communities against large corporations in arbitration.79 Since its inception in 2011, the CFPB has returned nearly $12 billion to 29 million victims of financial malfeasance, including more than $450 million to about 1 million fair lending abuse victims.80 The CFPB has also proposed collecting data to identify disparities in small business lending for entrepreneurs of color. This protective effort should move forward.81

The Trump administration and congressional Republicans have engaged in repeated efforts to weaken the CFPB.82 With the agency’s leadership changing in November 2017, its priorities—particularly regarding discrimination and predatory practices—may change as well. Policymakers and the public should be vigilant to ensure that it does not change direction to the detriment of borrowers. Such efforts would most certainly carry negative consequences for consumers—particularly people of color. Policymakers should continue to monitor developments at the CFPB and, if new leadership fails to promote or enforce borrower protections, states should consider filling the void.

Improve access to banking

Eighteen percent of African Americans do not have a bank account compared with just 3 percent of whites, making them more reliant on and vulnerable to predatory lending.83 Blacks are also more likely than whites to turn to alternative forms of credit, such as payday loans or car title loans.84 According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) survey in 2015, the most common reasons for being unbanked or underbanked cited among families was that they lacked sufficient money to keep in an account. Black and Hispanic households were also much more likely to report that they felt that banks were not interested in serving them.85 Greater access to affordable banking alternatives would help address the need that payday lenders, for example, currently serve. Better protections for prepaid cards and payday loans should ensure that companies compete on offering the best product—not on gouging consumers. Finally, consumers need access to safe, affordable products that build trust with customers who may be disconnected from the financial mainstream.

Improve college affordability

Blacks are much more likely to take on student debt in order to attend college and to default than their white counterparts. This is true regardless of whether or not the student completes their degree.86 According to a CAP analysis, nearly 50 percent of blacks who entered college in the 2003-04 school year defaulted on their student loans. Even among black individuals who completed a bachelor’s degree, the default rate was 23 percent.87 A recent Brookings Institution study projects that 70 percent of all black borrowers may ultimately experience default.88

The type of institution matters as well. Black students are more likely to attend for-profit colleges, and among students who entered college in 2003-04, three-quarters of black students who dropped out of private, for-profit colleges defaulted on their student loans.89 Access to quality, debt-free postsecondary education would reduce the cost and risk of college for all students and would have a disproportionately positive impact on African Americans who lack the generational wealth to help finance the cost of college. Leaving school with no education debt would also mean black students could start building wealth more quickly.

Improve income and employment

The data above show that merely increasing educational attainment and improving employment outcomes for blacks will not close the racial wealth gap. While a college education slightly narrows the wealth gap between blacks and whites, it remains quite large, suggesting that a college education is not the great equalizer it is often believed to be.90 Still, improving employment outcomes and access to quality, affordable education—along with improving the returns on that education—and employment can help narrow the gap.

It is important that policies addressing employment outcomes be focused on equitable access to the labor market and equitable returns to participation. The following recommendations focus on policies that will improve outcomes for black workers by strengthening bargaining power and lowering the cost of access to a variety of benefits, including health care, child care, paid family and medical leave, education, and training.

Support a job guarantee

While it is difficult to measure how much labor market discrimination accounts for the low wages and employment rates among black workers, it is clear that it does account for some share of the disparity. As a result, black workers generally have lower wages and less workplace bargaining power than whites. Academics such as William A. Darity Jr., Darrick Hamilton, and others have proposed implementing a federal job guarantee that would increase black workers’ access to stable employment and strengthen their bargaining power by offering up the government as an employer of last resort (ELR).91 If, acting as an ELR, the government hires all who are willing and able to work, then African Americans who meet those criteria would automatically access this employment.92 Darity has suggested that an ELR program could “eliminate the discriminatory unemployment penalty faced by blacks.”93 In its report titled “Toward a Marshall Plan for America,” CAP endorsed a job guarantee, and, in the coming months, CAP plans to release more detailed policy proposals outlining how a large-scale public employment program could be implemented in the United States.94

Improve opportunities for collective bargaining and modernize labor laws

Union density has been on the decline among all workers but has disproportionately affected African Americans, who are overrepresented among union workers.95 As more states implement so-called right-to-work laws that make it more difficult for workers to unionize, the odds that a worker will have the opportunity to bargain collectively has declined. In 1983, for example, nearly one-third of black workers were union members; by 2015, that number fell to 14 percent.96 Black workers, particularly black women workers, have been deeply engaged in efforts to expand collective bargaining. For example, the Fight for $15 campaign—the effort to increase the federal minimum wage to $15—and efforts to organize low-wage health care jobs have largely been led by black women.97

CAP has repeatedly called for policies that will increase worker power and make it easier for workers to engage in collective bargaining. In a recent report, CAP proposed four essential changes to the structure of collective bargaining that would help facilitate greater worker power.98 Those recommendations include: moving to industry-wide collective bargaining; establishing works councils; developing worker organizations; and modernizing labor law to ensure adequate protections and meaningful enforcement of worker rights.99

Raise the minimum wage

The federal minimum wage has been stuck at $7.25 per hour since 2009.100 The recent movement to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour would have a disproportionate positive impact on African Americans, who, though they make up roughly 12 percent of the U.S. population, represent 15 percent of those making less than $15 an hour.101 Policymakers should simultaneously seek to strengthen the Earned Income Tax Credit, which has a similar effect of boosting incomes for low-income families.102

Adopt fair chance hiring policies

A criminal record can have a substantial and negative impact on opportunities for employment. In recent years, states and the federal government have taken steps to unwind the damage done to communities of color by the carceral state by implementing fair chance policies such as ban-the-box and record clearing, as well as paying incarcerated individuals at least the minimum wage for any work they perform.103 These initiatives, along with efforts to ease the pathway to reentry for returning citizens, can help ensure more equitable access to employment.

Protect Social Security

The Social Security Act was signed into law by former President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935. The law, in part, created a program that would pay individuals 65 years old and older a continuing income after retirement. During the signing ceremony, President Roosevelt stated that the government could not protect citizens from every harm they may encounter in life, but that he wanted to “frame a law which will give some measure of protection to the average citizen and to his family against the loss of a job and against poverty-ridden old age.”104 Today, 37.8 million Americans collect Social Security benefits.105 Of those, nearly 3.3 million are black.106 Social Security is increasingly important for blacks, as they are more likely to encounter economic disadvantages during their lifetime. For example, in 2014, 30 percent of elderly black married couples and 50 percent of elderly black unmarried individuals relied on Social Security for 90 percent or more of their income.107 Proposals to raise the retirement age to older than 67 years would disproportionately harm blacks and all Americans with less wealth or poorer health outcomes by acting as a benefit cut. It is essential that conservative policymakers—who have shown an appetite for cutting essential safety net programs—do not harm Social Security.

Protect the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance

The Equal Opportunity Employment Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing laws that prohibit employment discrimination, including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.108 The Office of Federal Contract Compliance (OFCCP) works to ensure that government contractors or subcontractors are in full compliance with civil rights and labor laws.109 Contractors’ failure to be within compliance can lead to investigations, loss of the government contract, and other forms of relief to victims of any discrimination that occurred. In 2017, the Trump administration proposed consolidating the EEOC and the OFCCP into a single agency,110 which would severely hamper the federal government’s ability to enforce federal civil rights law.111 Rather than consolidating these agencies, policymakers should seek to ensure that both agencies have the resources needed to effectively carry out their missions.

Improve access to health care

As noted above, African Americans are more likely to experience negative income shocks and less likely to be able to draw on savings or access financial assistance from friends or family in an emergency, such as the onset of an illness. While the Affordable Care Act has lowered the uninsured rate among blacks by more than one-third, blacks are still more likely to be uninsured than whites.112 This is especially concerning given that blacks are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases.113 Reducing disparities in access to health care can have a significant impact on the financial well-being of blacks.

Expand access to paid leave and child care and ensure equal pay

Comprehensive work-family policies are essential for all workers but are even more crucial for black workers, particularly black women. Black women face discrimination in the workplace because of both their race and gender.114 Black women are less likely to have access to paid leave,115 and black families spend a much larger share of their income on child care than white families.116 Nationwide, the average cost of center-based child care for a 4 year old is $18,000 annually—about 42 percent of black families’ median income in 2015.117 Policies such as universal access to paid leave, child care, and pre-K education are essential and would have a disproportionate impact on black families’ ability to save money and access employment.118

Expand access to quality and affordable postsecondary education and workforce training

While a college education is not the sole solution to the racial wealth gap, improving disparities in educational attainment rates can help increase blacks’ wealth overall. It is essential, however, that policies focused on expanding access to postsecondary education are focused on expanding access to education that is both high-quality and affordable. As mentioned above, black students are more likely than white students to enroll in for-profit colleges and are 50 percent more likely to default on their student loans than white students at for-profit colleges.119 Black students who attend for-profit colleges are also more likely to default than black students attending public or private nonprofit institutions. For-profit colleges are often more costly than public alternatives and have worse student outcomes. Access to postsecondary education must emphasize both affordability and quality to ensure that black students receive a positive return on their investment.

Policymakers should take additional steps to ensure strong and sustained oversight of for-profit colleges. Race-based affirmative action policies can help ensure equitable access to postsecondary institutions.120

Finally, black workers need greater access to quality workforce training that can lead to good jobs, such as apprenticeship programs, and that can have a positive impact on wages.121 Apprenticeship programs pay $60,000 annually on average, yet black workers are typically concentrated in the lowest-wage fields and have lower completion rates than whites.122 Policies that prioritize outreach to African Americans and expand access to support services, as well as the strong enforcement of equal employment opportunity rules, can help expand access to apprenticeship programs and improve wages and completion rates among black apprentices.123

Conclusion

The gap in wealth between black families and white families remains persistently large. This is especially true in the wake of the Great Recession. Intentional policy interventions are required to make any significant progress in closing this gap. Maintaining the status quo translates into another 200 years before African Americans have the same level of wealth as their white counterparts.

The black-white wealth gap is a product of intentional systematic policy choices. The only way to correct this wrong is to make intentional systematic changes in response.

Appendix