One of the intriguing questions that lingered in the aftermath of President Barack Obama’s 2008 election was whether the voters who turned out to elect him were a historic but transitory phenomenon or whether they foreshadowed a dramatic and perhaps permanent change to the electoral map. At the center of this new electoral constituency were voters of color and, specifically, women of color. (see Text Box) In 2008, women-of-color voters turned out in historically high numbers and overwhelmingly voted Democratic, a phenomenon that was likely crucial to Democrats winning both the White House and Congress. In 2012, black women voted at a higher rate than any other group—across gender, race, and ethnicity—and, along with other women of color, played a key role in President Obama’s re-election. The following year, turnout by women of color in an off-year election helped provide Terry McAuliffe (D) the margin of victory in the 2013 Virginia gubernatorial election. Notably, both President Obama and Gov. McAuliffe lost the white women’s vote but overwhelmingly captured the votes of women of color.

As the 2008, 2012, and 2013 elections demonstrated, women of color are a key, emerging voting bloc with the potential to significantly affect electoral outcomes. In the past two years, more than 2 million women of color have joined the vote-eligible population. As more people of color participate in elections, demographic trends suggest that women of color will become increasingly prominent electoral players.

For purposes of the data analyses in this issue brief, “women of color” includes the women-of-color Census categories: Black or African American; American Indian and Alaska Native; Asian; Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander; and Hispanic or Latino—in other words, all groups of women except non-Hispanic white women. This brief also includes analyses of the three largest women-of-color groups—Latinas, black women, and Asian women—to provide additional context. A forthcoming report will delve more deeply into other constituencies within the women-of-color bloc. It is also important to note that the analyses presented here do not posit that women of color are a homogeneous group but rather that they represent an important demographic and dynamic in the nation that merit a closer look.

Notwithstanding this, political analysts, movement strategists, commentators, and candidates alike rarely acknowledge women of color as distinct political actors, with particular priorities, political preferences, and voting behaviors. To the extent that women of color are considered at all, it is most often as a part of broader efforts aimed at women, youth, or a specific racial or ethnic group.

This brief presents initial research aimed at re-evaluating prevailing assumptions about women of color as participants in our democracy. While not a monolithic group, women of color comprise an important demographic that can, when acting in concert on issues of common concern, have a profound impact not just on elections but on public policy as well. This impact is particularly salient in the state-level data presented in this brief. The data are from select states where women of color are concentrated in the largest numbers.

Women are the country’s largest voting bloc, and women of color are the fastest-growing segment of that group. When coupled with the fact that women of color make up just more than half of the emerging majority—in other words, people of color, who by 2043 will represent a majority of the country’s population—it becomes clear that this new reality points to a vastly altered political landscape, one in which women of color may wield great influence.

But why focus on women of color specifically? As the research in this brief implies, causes and candidates that speak to the unique interests that women of color share would surely benefit politically. However, far more important are those benefits that will flow to women of color once the democratic process is more responsive to their needs and concerns.

The troubling fact is that issues at the center of the lives of women of color rarely if ever take center stage in the political arena. Yet for them, having a consequential voice in our public policy discourse is not an abstraction; it is real, and the lack of it has direct and sometimes detrimental impacts on their world—their livelihoods, their bodies, their children, and their families.

The new research presented in this brief provides a snapshot of what this emerging constituency looks like. Fully unleashing the political power that women of color represent requires understanding who they are, knowing what issues are most important to them, and identifying how best to inspire them to participate regularly.

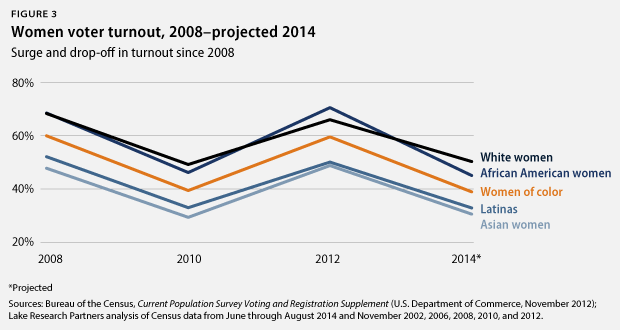

So far, however, this remains an aspiration: In the upcoming 2014 midterm elections, nearly one-third of the women of color who voted in 2012—an estimated 5.9 million voters—are expected to sit out the election, with the greatest drop-off—3.6 million—occurring among black women voters.

By beginning to paint the picture of women of color as a political constituency, this brief presents data grounded in trends that demonstrate increasing numbers of vote-eligible women of color with each new election cycle, women of color who vote in higher numbers than their male counterparts, and a voting bloc that is well on its way to becoming the majority of women voters overall. A forthcoming report will provide a more comprehensive analysis of women of color in the electorate.

Women of color are a growing force in the American electorate

Concentrated primarily along the Sun Belt and in the South, women of color are part of America’s new emerging majority and will increasingly be a powerful force in the electorate. This is particularly true in states with the highest proportion of vote-eligible women of color: Hawaii, New Mexico, California, and Texas. For example, California has experienced the largest increase in real numbers of any state—2.6 million more women of color since 2000—followed by Texas at 1.7 million.

Politicians, however, have often not focused on this potential voting bloc. But new research suggests that within this bloc lies a significant opportunity: As their numbers increase and their participation grows, women of color will increasingly have the chance to sway electoral results, influence which candidates run and win, and play a greater role in shaping the policy agenda. Again, this new reality becomes apparent when one considers that women of color are the fastest-growing segment of the country’s largest voting bloc: women.

Women voters have long been recognized as a powerhouse in the electorate. The gender gap—the difference between the percentages of women and men who support a particular party or candidate—has become a defining feature of American politics and a dynamic that campaigns regularly try to maximize or mitigate, depending on the political party. Women tend to vote more Democratic than men. Women also vote at higher rates and in higher numbers than men, and in the last election, women voters played decisive roles in several gubernatorial races and in seven high-profile Senate contests.

Fastest-growing segment of the women’s vote

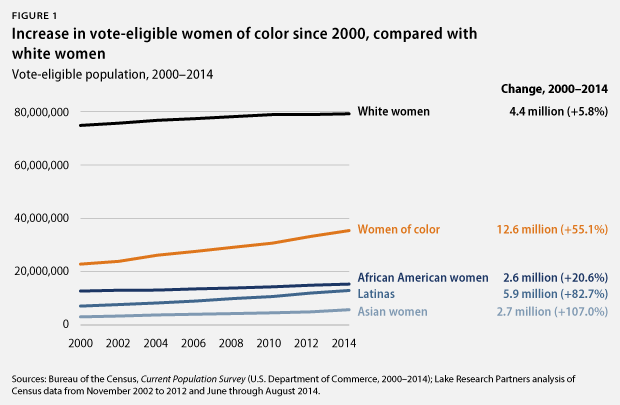

Women of color represent 74 percent of the growth in eligible women voters since 2000. While the voting-eligible population, or VEP, of white women has increased by less than 6 percent—about 4.4 million eligible voters—over the past eight election cycles, the VEP of women of color has increased by nearly 10 times that at 55 percent. This translates into more than 12 million new eligible women-of-color voters.

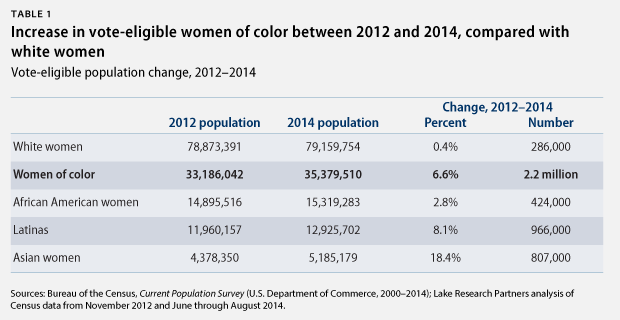

And while the VEP growth for white women has essentially plateaued since 2010, the upward trend in women of color’s VEP has become more dramatic with each successive election cycle, representing almost 90 percent of the overall VEP growth for women since 2012.

Among women of color’s VEP, Asian women and Latinas have grown at the fastest rates. Asian women saw the largest growth as a share of their size—an increase of 107 percent, or 2.7 million voters—since 2000. Latinas—who represent nearly half the growth of women of color’s VEP and almost 35 percent of the growth of the total VEP for women of all races—realized an increase of more than 82 percent, or 5.9 million additional vote-eligible Latinas since 2000.

Black women’s VEP has grown by 20.6 percent since 2000, adding 2.6 million voters. With more than 15 million eligible black women voters today, black women represent the largest share—43 percent—of vote-eligible women of color and 13.4 percent of all vote-eligible women.

The majority of vote-eligible people of color

These increases reveal a trend where people of color are, more generally, exercising more political influence as their overall numbers grow. Women of color constitute more than half of vote-eligible people of color at 53 percent—35 million eligible voters. Of the 4.1 million people of color added to the VEP since the 2012 election, 53.3 percent are women of color. Within their respective racial and ethnic groups, black women are 55 percent of black VEP, Latinas are 51 percent of Latino VEP, and Asian women are 54 percent of Asian VEP.

The significance of these trends becomes even more salient when examining the state-level data. For example, Latinas in Arizona experienced a VEP increase of 69.1 percent, or 244,000 more vote-eligible Latinas since 2000. And in every cycle since 2002, Latinas have comprised a larger share of the electorate in midterm elections than in presidential elections—a clear indication of their potential voting strength in future state and local elections.

Similar implications can be seen in the increasing voting strength of black women in the South. In Georgia since 2000, the VEP of black women increased by 10.3 percent, adding approximately 113,000 more black women to the population who are vote eligible. Black women in North Carolina have seen a VEP increase of 18 percent, or 130,000 more eligible voters since 2000. And in North Carolina, black women voters—like black women voters in Georgia—are more likely to register and turn out to vote than white women.

When energized, women of color participate at high rates that can affect electoral outcomes

Women of color are the most active segment of the growing people-of-color VEP and have demonstrated the potential to affect electoral outcomes, though they face obstacles to voting that must be overcome to realize their full participation.

Participation at high rates

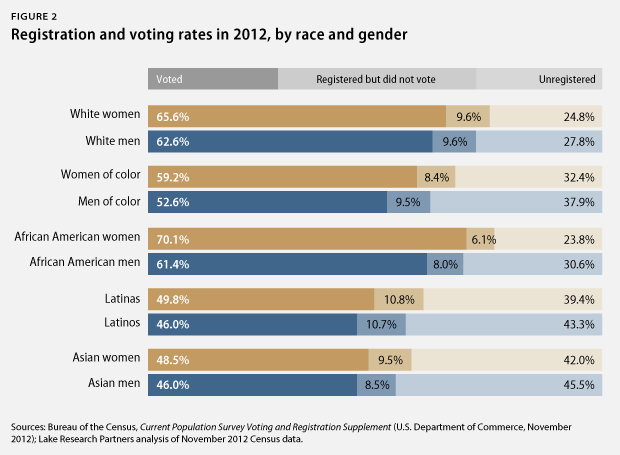

Already the majority of voters of color, the electoral power of women of color is amplified because they participate more than their male counterparts. In 2012, this was true across the board among Latina, black women, and Asian women voters.

Black women have the strongest turnout among women of color. In both 2008 and 2012, black women turned out in such large numbers that they were actually overrepresented in the electorate, meaning that they were a higher proportion of the electorate than of their share of the voting-eligible population. They participated at a slightly higher rate than white women in 2008, and were four points higher than white women in 2012.

In fact, in the last election cycle, black women registered and voted at the highest rate of any group of voters across race, gender, and ethnicity. Black women had a turnout rate of 70 percent. They were followed by white women at 66 percent, white men at 63 percent, and black men at 61 percent.

Influencing outcomes

The historic surge in the black women’s vote, together with a solid turnout of Latinas and Asian women, helped account for President Obama’s win of the women’s vote in 2012. Although he lost the white women vote—42 percent for voted for President Obama, and 56 percent voted for former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney (R)—President Obama captured the votes of 96 percent of black women, 76 percent of Latinas, and more than two-thirds of Asian women. This enabled him to win the overall women’s vote with 55 percent and, consequentially, re-election.

This exhibition of political might is not just reserved for presidential election years when Barack Obama is on the ballot. In 2013, an off-year election, women of color turned out in Virginia with virtually presidential levels of participation. This helped account for Terry McAuliffe’s capture of the overall women’s vote—51 percent—and his gubernatorial win. Notably, Gov. McAuliffe received only 38 percent of white women’s votes but an overwhelming 91 percent of black women’s votes.

Encountering obstacles to voting

Beyond effectively engaging women of color, to unleash their full power and potential, the United States must also address the many obstacles that exist to their full participation. Whereas white women and men were more likely than other groups to say they did not vote in 2012 because they did not like or had a lack of interest in the candidates or campaign issues, women of color reported a variety of impediments to voting.

Black women and Latinas, along with their male counterparts, reported the greatest structural barriers to voting. Black women and men were significantly more likely to report transportation challenges, and they were the most likely, along with Latinas, to be hindered by inconvenient polling places or too-long voting lines. This is particularly problematic given the fact that black women and Latinas are more likely than other women to cast their votes in person.

Asian women and Latinas were the most likely to report being too busy or having a conflicting work schedule as the reason for not voting. Black women were the most likely to cite illness or disability—either their own or a family member’s—as the reason they did not vote.

Moreover, in states across the country, policies are being implemented that will further constrain the ability of people of color and women to vote. These voter suppression measures have the potential to significantly curtail the political influence of women of color before it is fully realized.

In North Carolina, for example, where black women made up more than 23 percent of registered women voters in 2012, a controversial law that restricts early voting and eliminates same-day registration will disproportionately affect black women. Black women in North Carolina also cited disability or illness at 32.5 percent, registration issues at 22 percent, and transportation at 17.3 percent as specific challenges to voting in 2012.

Women of color are a key demographic and dynamic in the 2014 midterm elections

Nearly one-third of women-of-color voters who participated in the 2012 presidential election—30.3 percent—are expected to sit out the 2014 midterm elections. That translates into a staggering 5.9 million eligible voters who may stay home.

Women-of-color voter drop-off: 30.3 percent

- Estimated 5.9 million votes

African American women voter drop-off: 34.2 percent

- Estimated 3.6 million votes

Latina voter drop-off: 29.1 percent

- Estimated 1.7 million votes

Asian women voter drop-off: 25.8 percent

- Estimated 0.5 million votes

White women voter drop-off: 23.5 percent

- Estimated 12.2 million votes

The estimated drop-off rate for black women is particularly acute. Black women are projected to have the greatest drop-off among women—at a rate of 34.2 percent, or 3.6 million voters. Only 23.5 percent of white women and 20.4 percent of white men are projected to drop off.

Latina turnout levels are more consistent across midterm elections when compared with other women of color. They are projected to drop off at a rate of 29.1 percent; Asian women are projected to drop off at 25.8 percent.

The women-of-color drop-off rate carries important implications in states with high concentrations of women-of-color voters. A look at select state-level data is illustrative.

In Arizona, for example, nearly one-third of Latinas who voted in 2012—54,000 voters—are expected to stay home in the 2014 election. To put this in perspective, a one-point margin in an Arizona election represents about 19,900 votes. The projected drop-off rate among black women in Georgia is 29 percent, or 228,000 voters. In 2010, the last time Georgians voted to elect a new governor, the margin of victory was less than 260,000 votes. Half of all black women voters in North Carolina are expected to sit out the 2014 election—348,000 votes. The average margin of victory for the past three gubernatorial contests in North Carolina was less than 25,000 votes. And in Texas, which has experienced significant growth in the women-of-color voting-eligible population since 2000—165.6 percent for Asian women and 62 percent each for black women and Latinas—the projected women-of-color drop-off in 2014 represents more than 730,000 votes. The strength of these numbers has short-term implications not only for the 2014 elections but also for the long-term shape of the electorate.

While significant voter drop-off between presidential elections has come to be a common and even an expected occurrence, recent electoral history demonstrates that it need not be inevitable.

Conclusion

Women of color represent a growing force in American electoral politics, the impact of which is increasingly being felt in local, state, and federal races across the country. As women, these voters are the fastest-growing segment of the nation’s largest single voting bloc; as women of color, they are the largest and most active segment of people-of-color voters, who are emerging as the country’s majority.

Yet there are challenges to unlocking the force that women-of-color voters represent. Overcoming these challenges will require speaking to the specific and often shared concerns of women of color and addressing the obstacles to their full participation.

Women of color stand to benefit from a democratic process that is more responsive to their needs and receptive to their concerns. Fully unleashing the political power they represent is not merely about picking winners and losers in any given political contest; rather, it is to ensure that their interests are priorities on the policy agenda that shapes the contours of their lives. In this way, women of color will become full participants in the nation’s democracy, ensuring a better public discourse for them, their families, and, ultimately, the country as a whole.

Sources and methodology

Unless noted, all of the data in this report are from the Current Population Survey, or CPS, and the November CPS supplements on voting and registration:

The CPS is a monthly survey of about 50,000 households conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The CPS is the primary source of information on the labor-force characteristics of the U.S. population.

The CPS collects information on reported voting and registration by various demographic and socioeconomic characteristics in November of congressional and presidential election years.

The CPS uses a multistage probability sample based on the results of the decennial Census, with coverage in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The sample is continually updated to account for new residential construction.

2000–2012 data: The November 2000–2012 election and population data come from the Bureau of the Census’ 2000–2012 CPS Voting and Registration Supplements.

2014 population estimates: The 2014 population data were taken from an average of the Bureau of the Census’ CPS population numbers for June through August. These numbers were then used as the population size for turnout and registration projections.

Drop-off: This term refers to the loss of voters from 2012 to 2014. The average of registration and turnout in 2002, 2006, and 2010 was applied to 2014 population estimates to calculate predicted 2014 turnout and registration. Percentage drop-off is the difference between 2012 and predicted 2014 turnout as a percentage of 2012 turnout. Number drop-off is the number difference between 2012 turnout and predicted 2014 turnout.

Maya L. Harris is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School.

The author would like to thank Lake Research Partners, especially Celinda Lake and Cornelia Treptow, for its enthusiastic and diligent research and data analysis that contributed to this brief.