With the fall fast approaching, schooling has moved front and center in the public debate. Despite President Donald Trump’s repeated urging that public schools resume in-person classes, many school districts have already canceled in-person classes due to surging coronavirus cases across the United States. While a necessary public health measure, moving classes online raises significant racial equity issues that state, local, and federal policymakers must keep in mind as they craft legislative solutions for the fall. Black families and predominantly Black communities often have fewer economic resources—including less wealth and a smaller tax base—to support remote learning and ensure students have access to the internet and necessary devices such as computers and other equipment. Due to this massive Black-white wealth gap—and combined with coronavirus-induced job losses and housing insecurity—many Black children could quickly fall behind their white peers this fall.

Divergent access to the resources necessary for successful remote learning—such as books, computers, and other equipment—could further worsen racial disparities in educational outcomes. Due to systemic racism in the housing industry, predominantly Black neighborhoods tend to have lower property values. This, in turn, means the schools in these same neighborhoods have fewer financial resources—and these financial pressures have only increased and exacerbated racial inequities during the pandemic.

The flipside of underresourced schools is that parents will have to provide more of the resources themselves as schools transition to remote learning. The pressure on parents to provide these additional resources is greatest in communities where families have less wealth and thus less ability to support their children’s online education. Unless Congress provides the money so that local leaders and school districts can make necessary changes, many Black children are more likely to fall behind their white peers in education, stymying their educational progress.

How the racial wealth gap affects educational attainment

In the United States, wealth and education already feed into each other in an intergenerational cycle. Families with more wealth are able to provide more educational opportunities for their children, who are in turn able to capitalize on those opportunities in ways that create more wealth. This reinforcement of wealth through education and of education through wealth—when combined with the racially disparate economic and health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic—will only further widen existing racial wealth and education gaps. The intergenerational transmission of racial wealth inequality is playing out at rapid speed during the pandemic.

Wealth—the difference between what people own and what they owe—is key to families’ immediate financial security and their long-term economic mobility. During an economic crisis, families with more wealth are better able to protect themselves in the event of adverse personal outcomes such as temporary layoffs or more permanent job losses. In communities that experience widespread job losses, those who have better economic standing to begin with are better able to insulate their children against long-term setbacks. In the current pandemic, for example, wealth can provide emergency savings to help pay bills—especially rent or mortgage payments, which are key to maintaining housing stability.

Yet Black families have a median wealth of about 10 cents to every dollar of wealth of the median white family. In 2016, the last year for which data are available, the median Black family had about $17,150 in wealth while the median white family had about $171,000 in wealth. Because wealth is often passed on from one generation to the next, this massive wealth gap between Black and white families has persisted for centuries. As the authors of the comprehensive report “What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap” point out, “wealth begets more wealth.” Inheritances and gifts, access to beneficial social networks, and education are all mechanisms by which families pass on wealth to their children. Put simply, white families have more opportunities than Black families to give their children a leg up because they have access to more wealth.

Recent job losses have exacerbated the racial wealth gap

This past spring, school closures and the transition to online learning, while a necessary public health measure, required that families had access to financial resources to help pay for part of their children’s education. At the same time, many of these same parents lost part or all of their earnings from coronavirus-induced job losses and cuts in hours. Black workers, who tend to work in less stable jobs where they are at higher risk of getting laid off, are typically among the first to feel the brunt of an economic downturn. These jobs also make it more difficult for people to buy a house and save money. African American families then live in more financially precarious situations because they are less likely to own their own home and can be more easily evicted if they fail to pay their rent and because they have fewer savings outside their house than is the case for white families. Less wealth—reflected, among other things, in lower homeownership rates—makes it more difficult for Black families to afford reliable internet service and electronic devices, both of which are necessary for remote learning.

African Americans have experienced particularly large job losses in a labor market characterized by persistent racism and inequality, as the Economic Policy Institute’s Elise Gould and Valerie Wilson discuss in a recent report. Estimates based on census data show that 54.8 percent of Black workers said that they had lost incomes due to a job loss or cut in hours from late April to early June, compared with 45.8 percent of white workers.

The labor market pain has created housing instability for Black families to a much larger degree than was the case for white families. Estimates based on census data show that more than one-third of African Americans who experienced job-related income losses said that they either didn’t pay their mortgage or deferred their mortgage, compared with only 16.9 percent for white families with earnings losses. Among renters, 38.3 percent of Black families with income losses didn’t pay or deferred their rent, compared with 23.1 percent of white families in a similar situation.

Housing insecurity among Black families worsens the digital divide

The sharp labor market decline this past spring threatened the housing stability of Black families more quickly than it did for white families. This discrepancy reflects differences in emergency savings. Federal Reserve data, for example, show that 36.4 percent of African American homeowners and 56.4 percent of African American renters could not access $400 in an emergency in April 2020. In comparison, 24.4 percent of white homeowners and 50.9 percent of white renters had difficulties coming up with that amount in an emergency. Without emergency savings, many more Black homeowners and renters quickly faced trouble making their monthly payments than white homeowners and renters when they lost their jobs.

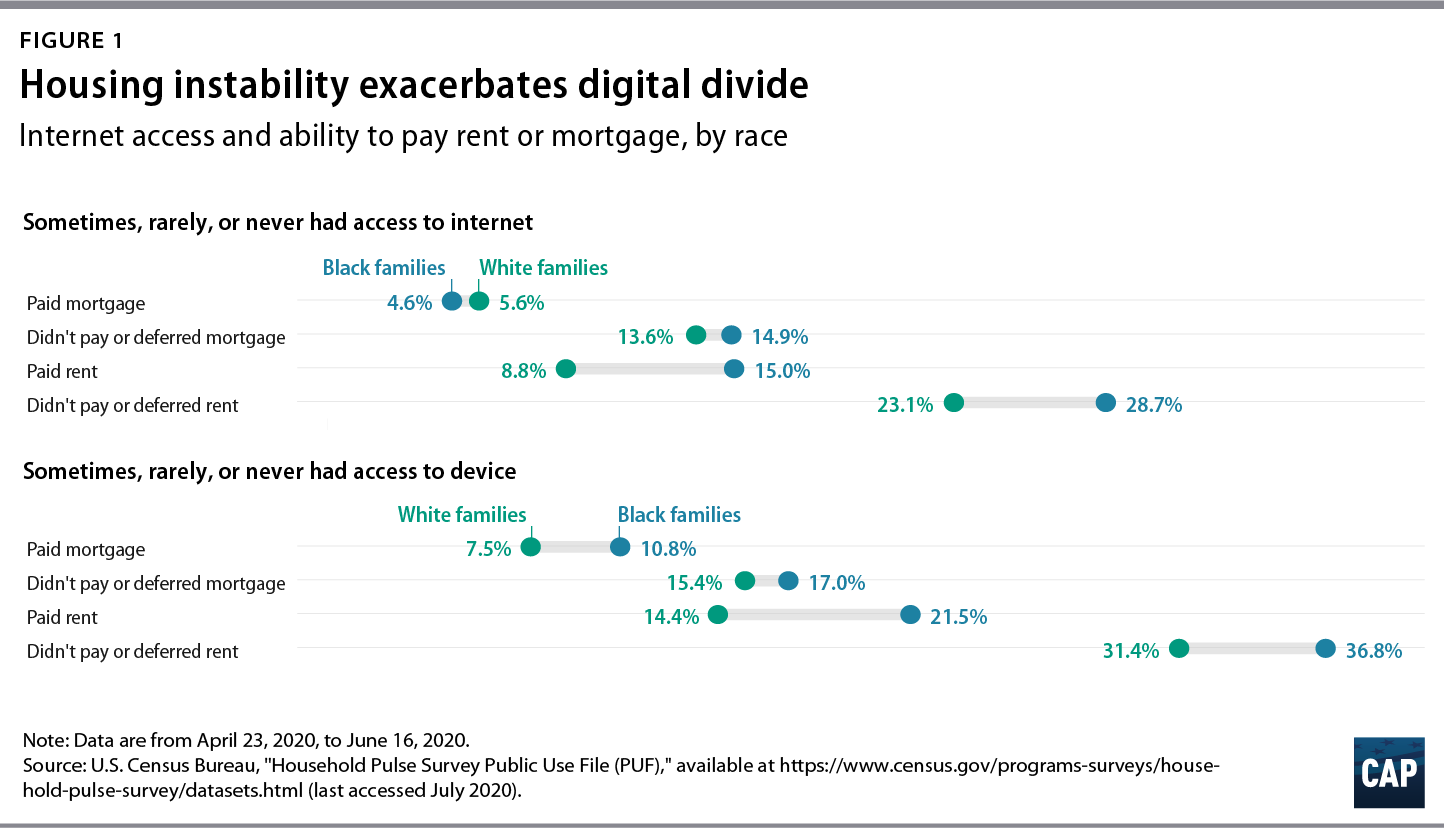

As a result, many Black families also had fewer savings to pay for tools such as internet access and electronic devices, which are crucial to maintaining children’s education. About 1 in 7 Black renters who have no trouble paying their current rent only have access to the internet for educational purposes sometimes, rarely, or never. This is almost three times as large a share as Black homeowners who had no trouble paying their mortgage. Importantly, most Black families rent rather than own their home. And the gap between Black homeowners and Black renters in having reliable internet access is much greater than among white homeowners and white renters. The same is true when it comes to access to electronic devices: Black renters are much less likely than either Black homeowners or white renters to have reliable access to these devices. (see Figure 1)

Homeownership is often a more financially stable housing option than renting because it allows families to have more predictable housing costs. Yet most Black families rent their homes, and many of those renters have had trouble paying their bills amid the current recession. These job losses have only exacerbated the lack of access to the internet and electronic devices. For example, 28.7 percent of Black parents with children in public or private schools who had trouble paying their rent in the previous month also said that they only sometimes, rarely, or never had access to the internet. And 36.8 percent of Black renters having trouble paying their rent said that they only sometimes, rarely, or never had access to devices for educational purposes for their children. (see Figure 1) These are much larger shares than for any other group of Black or white renters or homeowners. A lack of savings creates more housing instability for Black families, which leads to less access to the internet and electronic devices for remote learning.

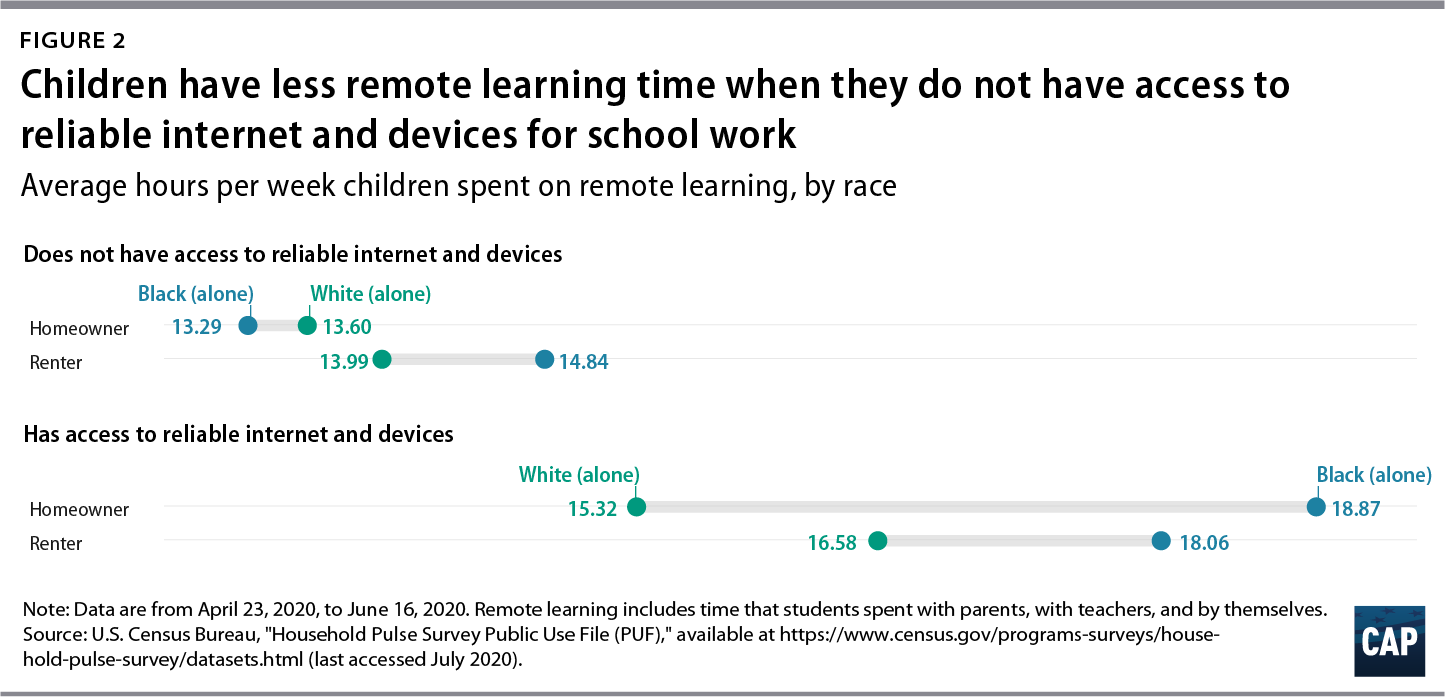

The lack of reliable internet or an electronic device for remote learning also correlates with fewer hours per week of teaching time. (see Figure 2) This correlation is much larger among Black families than white families, where the lack of reliable access to the internet and to devices is less pronounced. Unreliable internet access and a lack of consistent access to electronic devices reduces families’ time teaching children by two to three hours among Black families but only by one to two hours among white families. (see Figure 2) White families without reliable internet or devices are probably also less likely to simultaneously experience job loss and a lack of savings; as a result, they can afford to spend additional time with their children to offset the lack of internet and devices. While the short- and long-term impacts of coronavirus-related school closures and job losses on children’s educational outcomes cannot be measured yet, it is already clear that there are differential effects by race on access to educational resources as a result of the pandemic. In particular, the persistent and large Black-white wealth gap directly and immediately feeds into persistent educational gaps.

What schools and policymakers can do to offset this

As the debate over school reopenings heats up, policymakers must consider how wealth disparities between Black and white families will affect educational outcomes. Parents, as well as teachers and staff, need to feel safe sending their children back to school. When in-person schooling is not possible, parents must have the resources to help their children learn remotely. Schools and local government can provide reliable internet service and electronic devices to children—but they need more financial support. State and local governments will also need to ensure that families have stable housing by extending moratoriums on evictions and foreclosures.

Furthermore, Congress can do more to offset increasingly permanent job losses; for example, Congress can extend added unemployment benefits and protect public sector employment by helping state and local governments address large coronavirus-related budget deficits. Congress and employers can also make sure that parents can take paid time off from work to help their children with their education when schools are closed or remote learning is necessary. All of this assistance will be especially valuable to Black families, who often have much fewer savings than white families to tide them over in an emergency. Without targeted assistance to ensure that parents can maintain a quality education for their children, school closures and continued remote learning will widen the racial educational achievement gaps between Black and white children for the foreseeable future.

Dania Francis is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Christian E. Weller is a professor in the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston and a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.