Author’s note: CAP uses “Black” and “African American” interchangeably throughout many of our products. We chose to capitalize “Black” in order to reflect that we are discussing a group of people and to be consistent with the capitalization of “African American.”

Two years ago, Americans watched in horror as torch-bearing white nationalists marched through the campus of the University of Virginia chanting messages of hate and attacking local residents and university students. The chaotic rampage left three people dead and dozens more maimed and wounded. But this episode was not an isolated incident—racially motivated hate crimes are on the rise on college campuses across the nation.

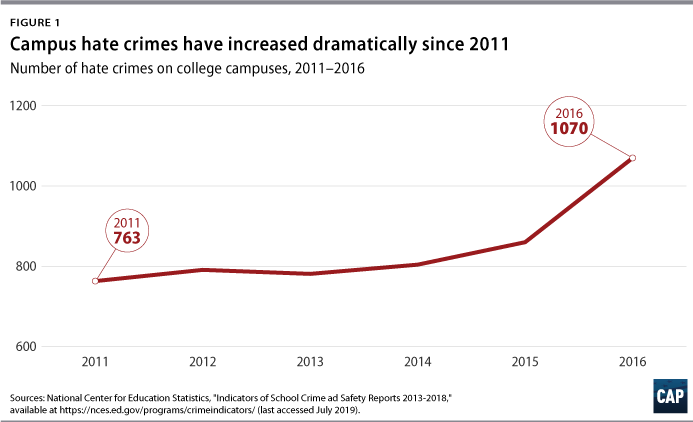

Beyond the physical danger that the resurgence of white nationalism imposes, incidents like these are also traumatic and undermine affected students’ mental health. Too often, however, university counseling centers lack the resources necessary to respond effectively to students’ needs. With more than 1,000 campus hate crimes reported in 2016 alone, universities must do more to slash fees, reduce wait times, and promote staff diversity at campus counseling centers nationwide. This column specifically focuses on the impact of racist hate violence.

Hate crimes and bias incidents are on the rise on college campuses

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) defines a hate crime as a “criminal offense which is motivated, in whole or in part, by an offender’s bias(es) against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.” Between 2011 and 2016, the NCES documented a 40 percent increase in campus hate crimes. (see Figure 1) In 2016, more than 1,000 hate crimes were committed on college campuses across the country. For years, racial bias has been the most common motivation for committing such crimes.

Hate does not always manifest as strictly criminal behavior. Therefore, hate crimes statistics cannot fully capture the pervasiveness of this dangerous ideology on college campuses. Campus bias incidents—which can include any “conduct that discriminates, stereotypes, excludes, harasses or harms anyone in [the university] community based on their identity”—are also on the rise. Between 2016 and 2018, the Anti-Defamation League documented at least 346 incidents of white supremacist propaganda on college campuses. Since 2018, the Southern Poverty Law Center has documented 434 incidents of white supremacist flyering on college campuses. Perhaps as a result, students of color are far less likely than white students to describe their campus as inclusive, and Black students in particular are more than twice as likely as white students to say the racial climate on their campus is poor.

Despite the abundance of evidence demonstrating that hate crimes and bias incidents are on the rise, limited reporting options suggest that many of these actions could go unrecorded. Most universities use online reporting systems to collect information on potential hate crimes and bias incidents and coordinate responses with other university departments and disciplinary committees. While anonymous online reporting mechanisms can be problematic in some spaces—the discriminatory profiling of students of color and students with disabilities is a persistent problem on college campuses—they are important in the context of hate and bias incidents.

The Steve Fund and Jed Foundation developed an Equity in Mental Health Framework to address structural barriers to care. They recommend adopting online reporting systems, as victims are more likely to report if they have the option to do so anonymously. In fact, all of the 2015-2016 incident reports at the University of Texas at Austin were filed using the interactive form available on their website, and roughly one-quarter of reports were filed anonymously. But 1 in 5 state flagship universities do not have an online bias reporting mechanism.* In other words, at least 216,000 students are currently denied the option to report these potentially traumatic experiences online with a guarantee of anonymity.

Campus hate crimes and bias incidents undermine student well-being

Experiences of racism can cause racial trauma, especially for Black students. The theory of racial battle fatigue maintains that “race-related stressors, such as exposure to racism and discrimination on campuses and the time and energy African American students expend to battle these stereotypes, can lead to detrimental psychological and physiological stress.” In a study of African American adults, race-related stress was a significantly more powerful risk factor than stressful life events for psychological distress. Racial trauma can manifest itself as physical and mental health disorders, and its effects can compound over time.

While research shows that mental health care can minimize psychological distress, Black and Hispanic adults are half as likely as their white counterparts to utilize mental health services.

Students affected by campus hate crimes face barriers to care

While university counseling centers are serving more students each year, many students do not utilize these resources for a variety of reasons, including long wait times, additional fees for service, and insufficient staff diversity.

Universities with larger student-to-mental-health-provider ratios can often have longer waiting periods for access to nonemergency mental health care. Longer waiting periods can be a significant barrier to care, especially for students of color, who are less likely to seek care in the first place. According to a new CAP analysis, the average student-to-counselor ratio among state flagship universities is approximately 1,300 to 1. The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors (AUCCCD) reported an average student-to-counselor ratio of 1 to 1,411 from July 2017 to June 2018. While center utilization rates and counselor bandwidth may vary from institution to institution, many would benefit from additional resources and support to ensure that wait times are not a barrier to care for any student.

Fees for mental health services are an additional barrier to care for students who have experienced racial trauma. In fact, a 2014 study found that 62 percent of students perceived cost as a barrier for individuals seeking help for mental health problems. Yet 1 in 4 state flagship universities require fees for counseling services in addition to the student health fee and tuition. While service fees vary, they can cost students upwards of $100 per visit. These fees disproportionately affect students of color due to persistent racial disparities in household wealth and income. According to a national study, 65 percent of students worry about having enough money to pay for school, not to mention additional fees for counseling services.

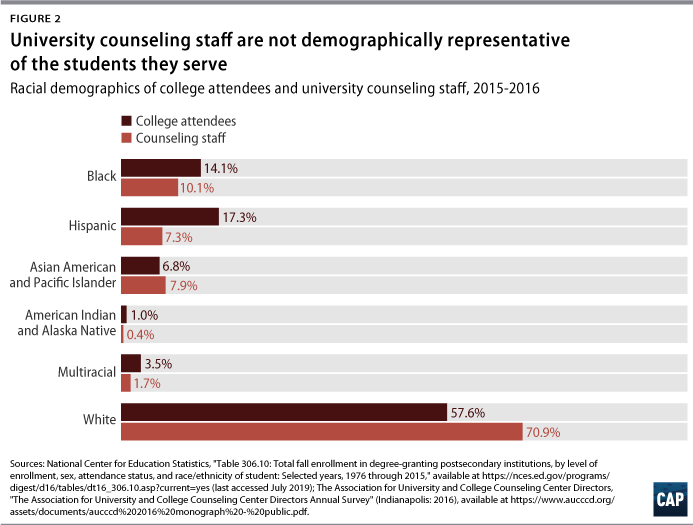

In addition to long wait times and fees, university counseling center staff are not representative of the student population they serve. In 2015, Hispanic individuals constituted 17.3 percent of all postsecondary students but just 7.3 percent of all university counseling center staff. In contrast, white individuals constituted 57.6 percent of enrolled students but 70.9 percent of university counseling center staff. Equal representation among mental health providers is critically important for managing racial trauma, as students of color may feel more comfortable seeking treatment from someone who shares their racial or ethnic identity and can better relate to their lived experience.

Conclusion

State flagship universities are supported with taxpayer dollars and therefore should be accountable to all residents, including residents of color. They can and must adjust their policies and practices to slash fees, reduce wait times, and promote staff diversity at campus counseling centers nationwide. In light of the rise of hate crimes on college campuses, universities should go beyond these standards to further address racial trauma on campus. The University of Iowa, for instance, has a comprehensive diversity page that is dedicated to addressing mental health in communities of color; the University of Maryland, College Park, has a drop-in hour for students of color interested in meeting with a counselor of color; and the University of Kentucky offers Bias Incident Support Services to all students who have experienced bias incidents.

Universities have a responsibility to protect and assist all students, regardless of their background, and administrators cannot allow racial trauma to go unaddressed. Many universities have expressed their commitment to diversity and inclusion, but this commitment must go beyond pamphlets and mission statements. This commitment should extend to providing adequate psychological resources. Universities should commit to ensuring that students of color have access to the mental health resources they need to succeed.

Victoria Nelson is a former intern for Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Special thanks to Connor Maxwell, policy analyst for Race and Ethnicity Policy at the Center, for his support on this project.

*Author’s note: The author’s calculations are based on data from college websites. See Methodology for details. Data are available upon request.

Methodology

For the purpose of this analysis, the author defines the student-to-counselor ratio as the total number of university undergraduate and graduate students divided by the total number of university counseling staff (excluding support staff, undergraduate interns, and peer mentors). Total student enrollment figures were drawn from university-published fall 2018 enrollment data.

Estimates for total counseling staff as of August 5, 2019 were determined based on online staff listings and outreach to university counseling centers. The author compiled estimates for the total number of mental health service providers, including but not limited to counselors, psychiatrists, social workers, postdoctoral trainees on July 30, 2019. The author then conducted outreach to universities on August 1-2, 2019, to verify the public-facing information and address any inconsistencies. The author was unable to verify the estimated number of counseling center staff at 20 universities.

This analysis contains several limitations. As the AUCCCD noted:

Although the ‘student-to-counselor’ ratio is frequently utilized in estimating the adequacy of existing counseling center staff, what is considered a ‘good’ ratio varies greatly from one institution to another, depending on factors such as the percent of the student population that utilizes the counseling center. For example, as the center utilization rate increases, the needed students-to-counselor ratio decreases.

Staff turnover rates may also vary by institution and time period (for instance, there are often fewer students on campus during the summer months). Online staff listings may also be outdated, which weaken the reliability of estimates for universities which the author was unable to contact. While annual data on the average number of counseling center staff by university would have been preferable for such an analysis, it is not available on a consistent basis. Therefore, readers should use caution when drawing broader conclusions based on this snapshot estimate.

Estimates for fees beyond initial individual counseling appointments are based on online listings from university counseling centers’ public-facing websites. Similarly, the author analyzed institution websites for the presence of an anonymous online option to report bias incidents on campus. Because the author was unable to independently verify fees for service and the presence of incident reporting systems, these estimates are aggregated across all state flagship universities. Counselor demographics data came from the AUCCCD’s annual report, which included analysis of 529 counseling centers across the country during the 2015-16 school year. The author compared these data with the National Center for Education Statistics’ report of fall enrollment by race in 2015.