Outdated laws and policies often fail to meet the needs of American families, especially when it comes to helping families successfully manage work and caregiving.1 Even when families are doing the right thing by supporting the people they love, a lack of basic labor standards makes it difficult, leading to stress, debt, and financial hardship. Despite Americans’ huge unmet need for policies that help them manage work and family responsibilities, such as paid leave, proposals put forward by President Donald Trump, lawmakers in Congress, and other conservative thinkers fail to address the needs of all families.2

Among the considerations in designing paid leave policies is ensuring access to them for a workforce with diverse family structures and caregiving responsibilities.3 Without inclusive definitions of who is considered “family,” paid leave policies may fail to support workers who provide care to so-called chosen family—individuals who form close bonds akin to those traditionally thought to occur in relationships with blood or legal ties.4 Despite the fact that the U.S. government first recognized the importance of chosen family during the Vietnam War—permitting federal employees to take funeral leave for the combat-related deaths of chosen family5—until recently, few paid leave policies have followed suit.6

Likely, part of what has driven this lack of recognition is that, while some research has explored the existence of chosen family,7 virtually no research has been conducted to examine its relationship to workplace leave policies. To address this gap, the Center for American Progress conducted a nationally representative survey to assess how often people in the United States take time off from work to care for a chosen family member with a health issue.

The reality of American families

Today’s American families do not fit the nostalgic image of a nuclear family headed by a different-sex couple—and the reality is, they never have. Currently, fewer than 20 percent of households adhere to the so-called nuclear family model of a married couple and their minor children.8 An increasing number of Americans live in multigenerational households: 85 million in 2014, up from 58 million at the beginning of the century.9 And a majority of unmarried mothers would contemplate raising their children with an adult who is not a romantic partner.10 Policymakers’ failure to recognize these realities has led to policies that have, at best, neglected the needs of millions of American families and, at worst, actively marginalized and separated families.

One area where policy has fallen especially short is recognizing and supporting family structures not based on legal or genetic ties. These chosen families form when two or more otherwise unrelated individuals develop a deep and significant personal bond akin to the bond that often exists between family members related by blood or legal ties, such as marriage or adoption.11 These are people of great importance who fill familial roles that might otherwise be filled by people related by law or biology.

Examples of chosen family abound. A previous CAP report collected examples of chosen family in just one of many roles they fill: caregivers. The report details the stories of Terrie, who cares for her partner’s children to whom she has no legal ties; Joanna, who was cared for by a roommate and a loved one when she was recovering from surgery; and Frederick, who simply wanted to be with his partner of more than five years, Brian, while Brian was in the hospital.12 Other examples of chosen family might include a parental older neighbor who comes over for dinner most evenings or best friends whose connection is so sibling-like that they become family. If one does not have chosen family, one likely knows someone who does.

While some research and anecdotal evidence detail the nature of chosen family relationships and the types of communities where these bonds may be more prevalent,13 comprehensive data on chosen family have not previously existed. This lack of data has meant that the extent to which Americans rely on chosen family members for caregiving support remains unexplored, as do the factors that predict whether an individual may need to access leave to care for chosen family. CAP’s analysis addresses these questions and reveals that public policy is falling dramatically short of families’ needs.

The need for paid leave policies that serve a range of family structures is broadly shared

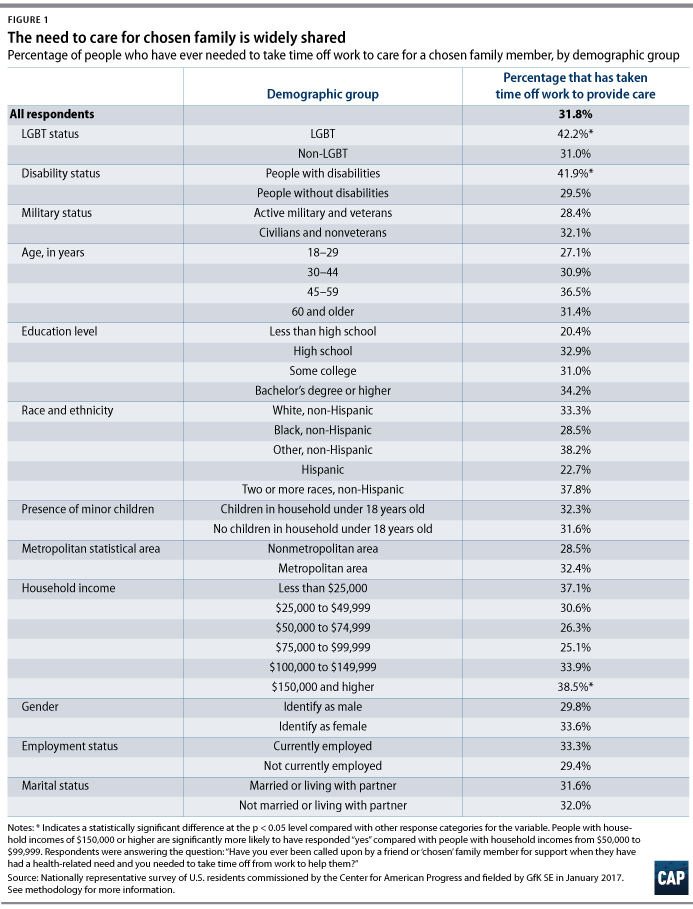

Supporting chosen family members is a remarkably common occurrence. New CAP data show that 32 percent of people in the United States report having taken time off work to care for a friend or chosen family member with a health-related need.

The data also show that virtually all kinds of people are similarly likely to report taking time off from work to care for the health-related needs of a chosen family member. This includes 28 percent of people who are active military or veterans and 32 percent of people living in households without children. The data show that across many racial and ethnic groups, age groups, education levels, income levels, and metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas, people are similarly likely to take off work to care for chosen family members. (see Methodology)

Yet while taking this time off to care for chosen family is a common occurrence, survey data show that some groups of people are more likely to report taking it than others, including LGBT individuals and people with disabilities. Forty-two percent of LGBT individuals report doing so, a significantly higher rate than non-LGBT individuals at 31 percent. Among people with disabilities, 42 percent reported taking time off to care for chosen family, compared with 30 percent of people without disabilities.14 These findings indicate that these individuals’ need for policies that recognize caregiving for chosen family as akin to caregiving for blood or legal relatives is particularly acute. See the Appendix for a full list of available demographics that CAP analyzed.

When considered together in a multivariate statistical model, certain demographic characteristics were shown to be particularly important in determining the likelihood that a respondent reported taking time off from work to care for chosen family. When holding other characteristics constant, an individual was significantly more likely to have taken time off work to care for a chosen family member if the individual identified as LGBT, reported having a disability, was older, identified as a woman, or was currently working. Being LGBT and having a disability were the strongest predictors of taking time off to care for chosen family. Educational attainment, military status, racial and ethnic identification, income, having minor children in the household, being married or living with a partner, and metropolitan status did not show statistically significant effects. (see Methodology)

While these data underscore the widely shared need for paid leave with an inclusive family definition, they also highlight the need for additional research. For example, more research should be done to understand why LGBT individuals and people with disabilities are more likely to need time to care for chosen families, even when controlling for other factors, such as age and income, which may predict this need. In the case of LGBT families, the need may stem from rejections by families of origin. For people with disabilities, chosen family caregiving may be particularly prevalent for people with certain kinds of disabilities. These questions are beyond the scope of this brief but merit serious research.

It is also important to recognize that these data do not paint a full picture of caregiving needs. Because these data reflect people who reported taking time off work to care for chosen family, they do not capture respondents who needed to provide care but were unable to take leave because their job did not offer paid leave or because they would have been penalized or possibly fired for doing so.15 Low-wage jobs are much less likely to offer paid leave16 and are more likely to penalize workers for taking time off.17 People of color, women, young people, and people with disabilities are a few groups who are disproportionately likely to work in low-wage jobs.18

Too few people have access to paid leave

One existing mechanism for providing support to caregivers is paid leave, including paid family leave or paid sick leave. Yet while virtually all families need to manage work and caregiving responsibilities, only 36 percent of employed CAP survey respondents reported having access to paid family leave. (see Methodology) And even these self-reported data likely overstate access for various reasons, such as confusion regarding respondents’ leave policies or taking other types of leave to provide caregiving. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 15 percent of civilian workers have specific access to paid family leave,19 and a recent report by the Pew Research Center revealed that many people use other kinds of paid leave—such as paid sick leave or personal leave—when family caregiving needs arise.20 Even if workers have access to paid leave policies, rarely do those policies include chosen family members.21

When people lack access to paid leave, the effects can be devastating. Research shows that it can increase financial hardship and lead to debt22 and that it contributes to increased inequality23 and harms health.24 The large number of workers without access to paid leave indicates a significant cumulative effect for society as a whole.

Proposals from President Trump and congressional Republicans will make balancing work and family harder

Despite President Trump’s claims that he will support working families, the agenda that he and his allies in Congress are pursuing not only fails to meet the needs of hardworking American families, but it also increases their struggles to manage work and family.25 Recent efforts to dismantle health care would undercut critical supports for caregivers,26 including essential home and community-based care services that help keep families together and are particularly important for people with disabilities and LGBT people.27 Efforts to gut basic labor protections,28 including the ability to collectively bargain, only add to families’ stress, further hampering their ability to cope.29

The paid leave policy that President Trump advanced during his campaign, which offered paid leave only to mothers of blood-related newborns, demonstrates a narrow, outdated understanding of families’ caregiving needs.30 This and other parental-leave-only proposals would fail to serve many kinds of families,31 including military and veteran families;32 families caring for seniors or adults with disabilities; and LGBT families who, for instance, adopt or foster children. As discussed above, the CAP survey results suggest that extending paid leave to those who need time off to care for the health needs of chosen family members would have a significant positive impact on two communities with experiences of marginalization—LGBT people and people with disabilities.

Conclusion

Recent steps forward in leave policies have recognized the diverse caregiving needs of many families. The federal government’s paid sick leave policy, which includes chosen family, has been in place for more than 20 years, and research has shown that this policy improves employee morale and increases workplace efficiency without substantially increasing sick time usage.33 State and city paid sick leave victories gained in the last half of 2016 will provide nearly 7 million people with access to paid sick time that includes chosen family.34 And some cities have enacted paid sick leave laws that include paid safe leave for domestic violence survivors and their loved ones, including chosen family.35 These critical steps forward provide important models for how best to structure policies that serve all kinds of families.

Methodology

To conduct this study, CAP commissioned and designed a survey—fielded by GfK SE—that surveyed 1,864 individuals about various life experiences including health care, discrimination, family support, and more. Among the respondents, 857 identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender, while 1,007 identified as heterosexual and cisgender/nontransgender. Respondents were diverse across factors such as income level, race, ethnicity, education, geography, disability status, age, and employment status. The survey was fielded online in English in January 2017. The results presented are nationally representative.

By “similarly likely,” the authors mean that these groups were not significantly different from their counterparts—for example, people with disabilities compared to people without disabilities—when compared in statistical tests performed by CAP. A finding is considered statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. See Figure 1 in the Appendix for a full set of comparisons.

To hold variables constant and to assess the relative importance of various factors, the authors estimated a probit model regarding the likelihood of being called upon and having to take time off from work to support a chosen family member with a health-related need. The independent variables in this model included all variables listed in Figure 1. (see Appendix)

Additional information about study methods and materials is on file with the authors.

Appendix

Katherine Gallagher Robbins is the director of family policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress. Laura E. Durso is the vice president of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center. Frank J. Bewkes is a policy analyst for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center. Eliza Schultz is a research assistant for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Ashe McGovern for their insight and expertise in crafting the survey instrument. The authors are also grateful to the following outside reviewers for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts: Jared Make from A Better Balance, Erin Malone of Forward Together, TJ Sutcliffe from The Arc, and Preston Van Vliet of A Better Balance and Family Values @ Work.