Rebecca D. Vallas, Director of Policy, Poverty to Prosperity Program, testified before the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee on November 4, 2015.

Rebecca D. Vallas, Director of Policy, Poverty to Prosperity Program, testified before the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee on November 4, 2015.

Thank you, Chairman Coats, Ranking Member Maloney, and Members of the Committee for the invitation to appear before you today. My name is Rebecca Vallas, and I am the Director of Policy of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.

The subject of today’s discussion is of the utmost importance to all of us as Americans, because any of us could find ourselves in the position of needing to turn to Social Security Disability Insurance at any time.

Imagine that tomorrow, while cleaning out your gutters, you fall off a ladder. You suffer a traumatic brain injury and spinal cord damage, leaving you paralyzed, unable to speak, and with significantly impaired short- and long-term memory. Unable to work for the foreseeable future, you have no idea how you are going to support your family. Now imagine your relief when you realize an insurance policy you have been paying into all your working life will help keep you and your family afloat by replacing a portion of your lost wages. It is our Social Security system.

The American people time and again have made clear their strong support for Social Security and their strong opposition to benefit cuts. I look forward to discussing how we can work together to strengthen this vital program so that it can continue to protect American men, women, and children for decades to come.

I will make three main points today:

- Social Security Disability Insurance provides basic but essential protection that workers earn during their working years. Social Security protects nearly all American workers in case of life-changing disability or illness. The modest benefits from Social Security Disability Insurance are vital to the economic security of disabled workers and their families.

- Eligibility criteria are stringent, and only workers with the most serious disabilities and illnesses qualify for benefits. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, the Social Security disability standard is among the strictest in the industrialized world. The vast majority of applicants are denied, and those who qualify for benefits often have multiple serious impairments, and many are terminally ill. Few are able to work at all.

- The recently passed Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 includes several provisions that will strengthen the program. The budget deal includes a temporary, modest reallocation of payroll taxes to prevent sharp across-the-board benefit cuts for beneficiaries, as well as several common-sense bipartisan steps to ensure program integrity.

Social Security Disability Insurance provides basic but essential protection that workers earn during their working years

Social Security was established nearly 80 years ago to ensure “the security of the men, women and children of the nation against the hazards and vicissitudes of life.” In 1956, the program was expanded to include Disability Insurance in recognition that the private market for long-term disability insurance was failing to provide adequate or affordable protection to workers.

Today, nearly all Americans—90 percent of workers ages 21 to 64—are protected by Social Security Disability Insurance. In all, more than 160 million American workers and their families are protected. About 8.9 million disabled workers—including more than 1 million veterans—receive Disability Insurance benefits, as do about 149,000 spouses and 1.8 million dependent children of disabled workers.

Social Security Disability Insurance is coverage that workers earn

Both workers and employers pay for Social Security through payroll tax contributions. Workers currently pay 6.2 percent of the first $118,500 of their earnings each year, and employers pay the same amount up to the same cap. Of that 6.2 percent, 5.3 percent currently goes to the Old Age and Survivors Insurance, or OASI, trust fund, and 0.9 percent to the Disability Insurance trust fund. Due to the interrelatedness of the Social Security programs, the two funds are typically considered together, though they are technically separate. The portion of payroll tax contributions that goes into each trust fund has changed several times throughout the years to account for demographic shifts and the funds’ respective projected solvency.

Benefits are modest but vital to economic security

The amount a qualifying worker receives in benefits is based on his or her prior earnings. Benefits are modest, typically replacing half or less of a worker’s earnings. The average benefit in 2015 is about $1,165 per month—not far above the federal poverty level for an individual.

Average disabled worker benefit (May 2015):

$1,165 per month

$13,980 per year

Federal poverty level for an individual (2015):

$980 per month

$11,760 per year

For more than 80 percent of beneficiaries, Disability Insurance is their main source of income. For one-third, it is their only source of income. Benefits are so modest that many beneficiaries struggle to make ends meet; nearly one in five, or about 1.6 million, disabled-worker beneficiaries live in poverty.

But without Disability Insurance, this figure would more than double, and more than 4 million disabled-worker beneficiaries would be poor. Disabled workers use their Social Security benefits to meet basic needs, such as rent or mortgage, gas and electric, food, and co-pays on needed—often life-sustaining—medications.

Workers who receive Disability Insurance are also eligible for Medicare after a two-year waiting period.

Social Security Disability Insurance provides protection most of us could never afford on the private market

And there is good reason to offer disability insurance through a public program such as Social Security: Private disability insurance is out of reach for most families. Just one in three private-sector workers has employer-provided long-term disability insurance, and plans are often less adequate than Social Security. Coverage is especially scarce for low-wage workers—just 7 percent of workers making less than $12 per hour have employer-provided disability insurance.

Workers in industries such as retail, hospitality, and construction are among the least likely to have employer-provided long-term disability coverage, and coverage is highly concentrated among white-collar professions. Access is even more limited on the individual market.

While it is difficult to compare Social Security Disability Insurance with private long-term disability plans given that private plans often exclude certain types of impairments—as well as workers with pre-existing conditions or in high-risk occupations—purchasing a plan of comparable value and adequacy on the individual private market would be unrealistic for most Americans.

Eligibility criteria are stringent, and only workers with the most serious disabilities and illnesses qualify for benefits

Disabled workers face a steep uphill battle to prove that they are eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance. Under the Social Security Act, the eligibility standard requires that a disabled worker be “unable to engage in substantial gainful activity”—defined as earning $1,090 per month in 2015—“by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.” In order to meet this rigorous standard, a worker must not only be unable to do his or her past jobs but also—considering his or her age, education, and experience—any other job that exists in significant numbers in the national economy at a level where he or she could earn even $270 per week.

A worker must also have earned coverage in order to be protected by Disability Insurance. A worker must have worked at least one-fourth of his or her adult years, including at least 5 of the 10 years before the disability began in order to be “insured.” The typical disabled worker beneficiary worked 22 years before needing to turn to benefits.

The OECD describes the U.S. disability benefit system, along with those of Canada, Japan, and South Korea, as having “the most stringent eligibility criteria for a full disability benefit, including the most rigorous reference to all jobs in the labor market.”

In practice, proving medical eligibility for Disability Insurance requires extensive medical evidence from one or more medical providers designated as acceptable medical sources—licensed physicians, specialists, or other approved medical providers—documenting the applicant’s severe impairment, or impairments, and resulting symptoms. Evidence from other providers, such as nurse practitioners or clinical social workers, is not enough to document a worker’s medical condition. Statements from friends, loved ones, and the applicant are not considered medical evidence and are not sufficient to establish eligibility.

Fewer than 4 in 10 claims for Disability Insurance are approved under this stringent standard, even after all levels of appeal. Many wait a year—and in many cases much longer—before receiving needed benefits. Underscoring the strictness of the disability standard, thousands of applicants die each year during the eligibility determination process. Of those who live long enough to receive benefits, one in five male and nearly one in six female beneficiaries die within five years of being approved. All told, Disability Insurance beneficiaries have death rates three to six times higher than other people of their age.

Social Security’s listing of impairments is organized according to 14 body systems

- Cardiovascular system

- Congenital disorders that affect multiple body systems

- Digestive system

- Genitourinary disorders

- Hematological disorders

- Endocrine disorders

- Immune system disorders

- Malignant neoplastic diseases

- Mental disorders

- Musculoskeletal disorders

- Neurological disorders

- Respiratory system

- Skin disorders

- Special senses and speech

Beneficiaries have a wide range of significant disabilities and debilitating illnesses and many have multiple impairments

Disabled workers who receive Disability Insurance live with a diverse range of severe impairments. The Social Security Administration categorizes beneficiaries according to their “primary diagnosis,” or main health condition. As of 2013, the most recent year for which impairment data are available:

- 31.5 percent have a “primary diagnosis” of a mental impairment, including 4.2 percent with intellectual disabilities and 27.6 percent with other types of mental disorders such as schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, or severe depression.

- 30.5 percent have a musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorder.

- 8.3 percent have a cardiovascular condition such as chronic heart failure.

- 9.3 percent have a disorder of the nervous system, such as cerebral palsy or multiple sclerosis, or a sensory impairment such as deafness or blindness.

- 20.4 percent include workers living with cancers; infectious diseases; injuries; genitourinary impairments such as end stage renal disease; congenital disorders; metabolic and endocrine diseases such as diabetes; diseases of the respiratory system; and diseases of other body systems.

A fact not well captured by Social Security’s data—given that beneficiaries are categorized by “primary diagnosis”—is that many beneficiaries have multiple serious health conditions. For instance, nearly half of individuals with mental disorders have more than one mental illness, such as major depressive disorder and a severe anxiety disorder. Individuals with mental illness are also at greater risk of poor physical health: The two leading causes of death for individuals with mental illness are cardiovascular disease and cancers. Musculoskeletal disorders commonly afflict multiple joints, and individuals with musculoskeletal impairments—typically older workers whose bodies have broken down with age—commonly suffer additional health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease.

A fact not well captured by Social Security’s data—given that beneficiaries are categorized by “primary diagnosis”—is that many beneficiaries have multiple serious health conditions. For instance, nearly half of individuals with mental disorders have more than one mental illness, such as major depressive disorder and a severe anxiety disorder. Individuals with mental illness are also at greater risk of poor physical health: The two leading causes of death for individuals with mental illness are cardiovascular disease and cancers. Musculoskeletal disorders commonly afflict multiple joints, and individuals with musculoskeletal impairments—typically older workers whose bodies have broken down with age—commonly suffer additional health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease.

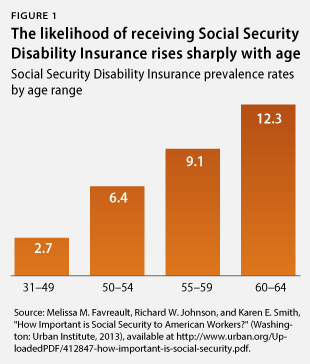

Most beneficiaries are older and had physically demanding jobs

Most beneficiaries of Disability Insurance—7 in 10—are in their 50s and 60s, and the average age is 53. The fact that most beneficiaries are older is unsurprising given that the likelihood of disability increases sharply with age: A worker is twice as likely to experience disability at age 50 as at 40, and twice as likely at 60 as at 50. Before turning to Social Security, most disabled-worker beneficiaries worked at “unskilled” or “semi-skilled” physically demanding jobs. About half—53 percent—of disabled workers who receive Disability Insurance have a high school diploma or less. About one-third completed some college, and the remaining 18 percent completed four years of college or have further higher education.

Few are able to work at all

Disability Insurance beneficiaries are permitted and encouraged to work. They may earn up to the substantial gainful activity level—$1,090 per month in 2015—with no effect on their monthly benefits. However, given how strict the Social Security disability standard is, most beneficiaries live with such debilitating impairments and health conditions that they are unable to work at all, and most do not have earnings. According to a recent study linking Social Security data and earnings records before the onset of the Great Recession in 2007, it was found that fewer than one in six, or 15 percent, of beneficiaries had earnings of even $1,000 during the year. The vast majority of those who worked earned very little, and just 3.9 percent earned more than $10,000 during the year— hardly enough to support oneself.

For those whose conditions improve and who wish to test their capacity to work, Social Security Administration policies include strong work incentives and supports. Beneficiaries whose conditions improve enough that they are able to earn more than the substantial gainful activity level are encouraged to work as much as they are able to and may earn an unlimited amount for up to 12 months without losing a dollar in benefits. Those who work above the substantial gainful activity level for more than 12 months enter a three-year “extended period of eligibility,” during which they receive a benefit only in the months in which they earn less the substantial gainful activity level. After the extended period of eligibility ends, if at any point in the next five years their condition worsens and they are not able to continue working above that level, they can return to benefits almost immediately through a process called “expedited reinstatement.” This process allows them to restart their needed benefits without having to repeat the entire, lengthy disability determination process. These policies are extremely helpful to beneficiaries with episodic symptoms or whose conditions improve over time.

If a significant share of beneficiaries were able to do substantial work, one would expect a sizable percentage to take advantage of the previously described work incentives in order to maximize their earnings without losing benefits. But beneficiaries’ work patterns indicate otherwise. Less than one-half of 1 percent of beneficiaries maintain a level of earnings just below the substantial gainful activity level. Further underscoring the strictness of the Social Security disability standard, even disabled workers who are denied benefits exhibit extremely low work capacity afterward. A recent study of workers denied Disability Insurance found that just one in four were able to earn more than the substantial gainful activity level postdenial.

How does the United States compare with other countries?

The Social Security disability standard is among the strictest in the industrialized world. As previously noted, the OECD describes the U.S. disability benefit system, along with those of a handful of other nations, as having “the most stringent eligibility criteria for a full disability benefit, including the most rigorous reference to all jobs in the labor market.”

Social Security Disability Insurance benefits are less generous than most other countries’ disability benefit programs. With Disability Insurance benefits replacing 42 percent of previous earnings for the median earner, the United States is ranked 30th out of 34 OECD member countries in terms of replacement rates.43 Many countries’ disability benefit programs replace 80 percent or more of previous earnings.

By international standards, the United States spends comparatively little on disability benefits. In 2009, U.S. spending on Social Security Disability Insurance equaled 0.8 percent of gross domestic product, or GDP, again putting the United States near the bottom—27th out of 34 OECD member countries—in spending on equivalent programs. On average, OECD member countries spend 1.2 percent of GDP on their equivalent programs, and many—such as Denmark at 2 percent, the United Kingdom at 2.4 percent, and Norway at 2.6 percent—spend significantly more.

The share of the U.S. working-age population receiving Disability Insurance benefits—about 6 percent—is roughly on par with the OECD average of 5.9 percent.

In drawing international comparisons, it is well worth noting that in addition to more generous disability benefit systems with less rigorous eligibility standards, European nations tend to have universal paid leave policies, more generous health care systems, higher levels of social spending generally, and more regulated labor markets than the United States.

Growth in the program was expected and is mostly the result of demographic and labor market shifts

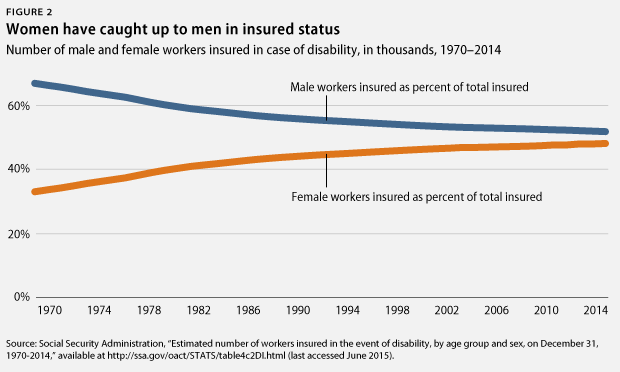

As long projected by Social Security’s actuaries, the number of workers receiving Disability Insurance has increased over time, due mostly to demographic and labor market shifts. According to recent analysis by Harvard economist Jeffrey Liebman, the growth in the program between 1977 and 2007 is due almost entirely—at 90 percent—to the Baby Boomers aging into the high-disability years of their 50s and 60s and the rise in women’s labor force participation. Importantly, as Baby Boomers retire, the program’s growth has already leveled off and is projected to decline further in the coming years.

Due to the importance of these demographic factors, Social Security’s actuaries analyze trends in benefit receipt using the “age-sex adjusted disability prevalence rate,” which controls for changes in the age and sex distribution of the insured population, as well as for population growth. The age-sex adjusted disability prevalence rate was 4.6 percent in 2014 compared with 3.1 percent in 1980.

Key drivers of the program’s growth include:

- Aging population. The risk of disability increases sharply with age. A worker is twice as likely to be disabled at age 50 as at 40, and again twice as likely at age 60 as at 50. Born between 1946 and 1964, Baby Boomers have now aged into their high-disability years, driving much of the growth in Disability Insurance.

- Increase in women’s labor force participation. Whereas previous generations of women had not worked enough to be insured in case of disability, women today have essentially caught up with men when it comes to being insured for benefits based on their work history.

- Population growth. The working-age population—ages 20 to 64—has grown significantly, by 43 percent between 1980 and 2014. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that population growth alone—even if the population were not aging—would have resulted in an additional 1.25 million beneficiaries during that time period.

- Women’s catch-up in rates of receipt. Just as women have caught up with men in terms of having worked enough to be insured for Disability Insurance, the gender gap in rates of receipt of benefits has closed as well. As recently as 1990, male workers outnumbered female workers by 2-to-1, whereas today, nearly 48 percent of workers receiving Disability Insurance are women.

- Increase in Social Security retirement age. The increase in the Social Security retirement age from 65 to 66, and ultimately to 67, has played a role as well, as disabled workers continue receiving Social Security Disability Insurance for longer before converting to retirement benefits when they reach full retirement age. About 5 percent of Social Security Disability Insurance beneficiaries are ages 65 and 66.

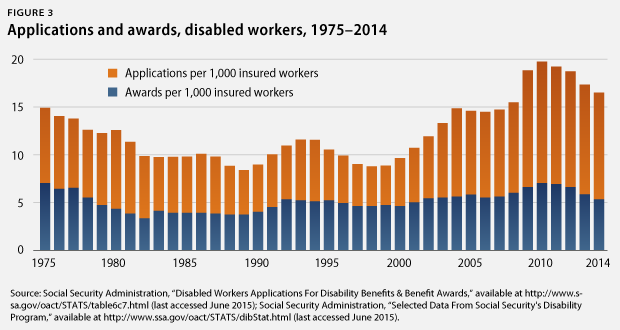

The Great Recession in context

Social Security’s actuaries note that the main effect of the recent economic downturn was lower revenue through payroll tax contributions—not an increase in beneficiaries. While recessions are typically associated with sharp increases in applications for Social Security Disability Insurance, they have a much smaller impact on awards. The most recent downturn was no exception, and Social Security’s actuaries estimate that just 5 percent of the program’s growth from 1980 to 2010 is due to the recession, likely due to workers with disabilities being disproportionately laid off from employer payrolls when times got tight.

It is important to note that while applications increased during the Great Recession, the award rate—the share of applications approved for benefits—declined, indicating that applicants who did not meet the rigid disability standard were screened out. A study by Social Security’s watchdog examined the 11 states with the highest unemployment rates and found that award rates had dropped in all of them.

Moreover, a recent National Bureau of Economic Research study found “no indication that expiration of unemployment insurance benefits causes Social Security Disability Insurance applications.” Furthermore, a recent White House Council of Economic Advisers report examining labor force participation trends since 2007 found that the increase in the number of disabled workers receiving Disability Insurance has had a minimal effect on labor force participation, noting, “In fact, if anything, the increase in disability rolls since 2009 have been somewhat lower than one would have predicted given the predicted cyclical and demographic effects.”

The program’s financial outlook

While the OASI fund and the Disability Insurance fund are technically separate, they are typically considered together due to the interrelatedness of Social Security’s programs. For example, Social Security’s programs share the same benefit formula, beneficiaries regularly move between programs, and changes to one program—such as raising the retirement age—affect both trust funds. Since Social Security Disability Insurance was established in 1956, Congress has repeatedly, on a bipartisan basis, reallocated the share of payroll taxes that goes into each trust fund to keep both funds on sound footing amid changing demographics. Payroll tax reallocation has occurred repeatedly over the years whenever needed, roughly equally in both directions.

1983 Social Security reforms worsened Social Security Disability Insurance’s financial health to an extent that the 1994 adjustments only partially addressed

Prior to the recently passed budget deal, the last round of major changes to Social Security occurred in 1983. Notable components of the 1983 legislation included an increase in the Social Security retirement age from 65 to 67 and a cut in the share of the payroll tax allocated to the Disability Insurance trust fund. At the time of the 1983 changes, the OASI fund was facing insolvency, while the Disability Insurance fund was healthy.

The impact of these changes on the Disability Insurance trust fund has been significant. As noted above, increasing the full retirement age worsens the state of the Disability Insurance trust fund since it causes workers to remain on Disability Insurance for longer before converting to Social Security retirement benefits. Additionally, the cut in the share of the payroll tax allocated to Disability Insurance—which had been on schedule to rise from 0.825 to 1.1 percent in 1990—has caused the Disability Insurance fund to receive significantly less revenue in the years since.

In 1994, spurred by the worsening state of the Disability Insurance fund, Congress increased Disability Insurance’s share of the payroll tax to 0.9 percent—an improvement over the 0.5 percent to 0.6 percent the fund had been receiving after the 1983 legislation but still significantly lower than the 1.1 percent it had been scheduled to receive prior to the 1983 changes. Disability Insurance’s share of the payroll tax remains at 0.9 percent. Had it risen to 1.1 percent as scheduled, we would not be where we are today, and action to shore up the fund would not be needed by late 2016.

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 strengthens Social Security Disability Insurance

The recently passed budget deal includes several provisions to strengthen the program. Most importantly, it provides for a modest, temporary reallocation of payroll taxes to ensure that all promised Disability Insurance benefits can be paid through 2022, avoiding sharp and unnecessary across-the-board benefit cuts. While it is disappointing that the reallocation in the Bipartisan Budget Act falls short of the president’s proposal to equalize the solvency of the trust funds and put both on sound footing until 2034, the reallocation provided for in the budget deal will prevent deep benefit cuts that would have been devastating to beneficiaries’ financial security and well-being.

The budget deal also includes a number of important bipartisan measures to enhance program integrity, such as:

- Expanding Cooperative Disability Investigation Units, or CDIs, to all 50 states

- Boosting cap adjustment spending for program integrity under the Budget Control Act to support the expansion of CDI units and continuing disability reviews

- Allowing for the use of electronic payroll data from commercial databases to enable the Social Security Administration to reduce improper payments

- Closing unintended loopholes such as “file and suspend” to prevent individuals from obtaining greater benefits than Congress intended

- Requiring medical review—by a qualified physician, psychiatrist, or psychologist—of initial disability determinations

Additionally, the budget deal restores the Social Security Administration’s demonstration authority for the Disability Insurance program. It also provides for a demonstration project to test replacing the “cash cliff” with a “benefit offset,” such that an individual’s monthly benefit would be reduced by $1 for every $2 of earnings in excess of a threshold.

Looking past 2022, there are a number of options for ensuring the long-term solvency of the overall Social Security system without cutting already modest benefits—something that polls consistently confirm most Americans oppose. One frequently discussed policy option is eliminating the cap on earnings that are subject to payroll taxes so that the 5 percent of workers who earn more than the cap would pay into the system all year as other workers do. A recent survey conducted by the nonpartisan National Academy of Social Insurance found overwhelming support for a reform package that included this and other revenue-enhancing features, while also boosting benefits. An array of legislation introduced within the past few years has included this and other approaches to strengthen Social Security, reflecting their growing popularity.

Adequate administrative funding is needed to address backlogs and ensure program integrity

The Social Security Administration’s administrative costs are less than 1.3 percent of the benefits it pays out each year. The agency requires sufficient administrative funding not only to process applications for and payment of benefits but also to perform important program integrity work, such as pre-effectuation reviews of disability determinations and continuing disability reviews to ensure benefits are paid only as long as the individual remains eligible.

In recent years, the agency’s administrative budget has been significantly underfunded. Congress appropriated more than $1 billion less for the Social Security Administration’s Limitation on Administrative Expenses, or LAE, than President Barack Obama’s request between fiscal years 2011 and 2013. Additionally, in FY 2012 and 2013, Congress appropriated nearly $500 million dollars less for the agency’s program integrity activities—such as continuing disability reviews—than the Budget Control Act of 2011 authorized. As a result, during a time of increasing workload due to the Baby Boomers entering retirement and their disability-prone years, the agency lost more than 11,000 employees—a 13 percent drop in its workforce—hampering its ability to serve the public and keep up with vital program integrity activities. In a positive step, the FY 2014 budget bill provided the agency with full funding at the FY 2014 Budget Control Act levels for program integrity activities. But in FY 2015, the Social Security Administration received $218 million less for LAE than the president’s request. This directly translates into diminished capacity for program integrity efforts. President Obama’s FY 2015 budget request would have allowed the Social Security Administration to complete 98,000 more continuing disability reviews during this fiscal year.

Adequate resources are needed to support claims processing and disability determinations at the initial levels so that the right decision can be made at the earliest point in the process and needless appeals can be avoided. Additionally, adequate resources are urgently needed to address the tremendous backlogs that have emerged at the administrative law judge, or ALJ, hearing level. The average wait time for an ALJ hearing is well over one year—closer to two years in many hearing offices—and more than 1 million applicants are currently waiting for a hearing.

Additionally, the agency requires sufficient administrative funding to conduct important program integrity activities, such as continuing disability reviews to ensure benefits are paid only as long as the individual remains eligible. Continuing disability reviews are estimated to save some $9 in benefits for every $1 spent on reviews, yet the agency reports a backlog of nearly 1.3 million reviews due to inadequate funding. In an important step forward, the cap adjustments for program integrity funding included in the recent budget deal will provide the Social Security Administration with $484 million in additional funding between FY 2017 and FY 2020 to conduct continuing disability reviews and other critical program integrity activities.

Policies to give workers with disabilities a fair shot at employment and economic security

Supporting work by people with disabilities has long been a bipartisan priority, and considerable progress has been made toward removing barriers to employment, education, and accessibility over the past several decades. The Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, enacted 25 years ago, prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability and mandates that people with disabilities must have “equal opportunity” to participate in American life. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, enacted the same year, requires that students with disabilities be provided a “free appropriate public education” just like all other students.

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, or WIOA, expanded access for people with disabilities to education and training programs, programs for transition-age youth and young adults transitioning to adulthood, vocational rehabilitation, and more. And most recently, the Achieving a Better Life Experience, or ABLE, Act, which was signed into law at the end of 2014, permits people with qualifying disabilities to open special savings accounts without jeopardizing eligibility for programs such as Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income, or SSI.

But much work remains. In order to break the link between disability and economic insecurity, we must enact public policies that give workers with disabilities a fair shot.

A great deal of attention is often paid to the Social Security Disability Insurance program, with some calling for a fundamental overhaul of this vitally important program in the name of increasing employment among people with disabilities. Yet as noted by the National Council on Disability, it is often forgotten that:

Receipt of Social Security disability benefits is merely the last stop on a long journey that many people with disabilities make from the point of disability onset to the moment at which disability is so severe that work is not possible. All along this journey, individuals encounter the policies and practices of the other systems involved in disability and employment issues.

As noted previously, most Disability Insurance beneficiaries live with such significant disabilities and severe illnesses that substantial work is unlikely. Moreover, a great many Americans with disabilities who do not receive Disability Insurance face barriers to employment and economic security. To achieve the goal of ensuring that workers with disabilities have a fair shot at gainful employment and economic security, policymakers must step back and take a much broader look at the policy landscape and how it affects workers with disabilities.

In order to give people with disabilities a fair shot at employment, policymakers should:

- Raise the minimum wage. Raising the minimum wage to $12 per hour would boost the incomes of many workers with disabilities, who are especially likely to work in low-wage jobs, and would help reduce the disability pay gap.

- Strengthen the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC. Boosting the EITC for workers without dependent children would benefit more than 1 million workers with disabilities, who are more likely to work in low-wage jobs and who are also less likely to have children.

- Expand Medicaid. Expanding Medicaid—as 19 states continue to refuse to do—would make it possible for more low-income Americans to access preventive care and reduce financial strain for low-income individuals with disabilities.

- Ensure paid leave and paid sick days. Ensuring paid leave—such as through the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act, or FAMILY Act—as well as paid sick days—as the Healthy Families Act would do—would benefit both workers with disabilities and the one in six workers who care for family members with disabilities.

- Improve access to long-term supports and services. Ensuring access to long-term services and supports for workers with disabilities through a national Medicaid buy-in program with generous income and asset limits would remove a major barrier for employed individuals with disabilities who are working their way out of poverty. An enhanced federal match could ensure that there are no additional costs to states. No person with high support needs should be required to remain poor in order to gain access to the services and supports they need in order to work.

- Institute a disabled worker tax credit. This idea, which has received bipartisan support over the years, would enable workers with disabilities to offset the additional costs associated with their disabilities, thus reducing hardship and making it possible for them to work. The credit should be made refundable to ensure that low-income workers can access its benefits. Other important questions that need to be explored include which eligibility criteria to use and whether to structure it as a credit with a flat amount for all workers who qualify or to tie its value to verifiable costs.

- Adequately fund vocational rehabilitation. Adequate funding for the vocational rehabilitation system is needed to ensure that all eligible individuals are able to access vocational rehabilitation services when they need them.

- Create subsidized employment opportunities. A national subsidized jobs program—modeled after states’ successful strategies using Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Emergency Fund dollars in 2009 and 2010—is a policy solution with bipartisan appeal. As outlined in the CAP report “A Subsidized Jobs Program for the 21st Century,” subsidized jobs, in which government reimburses employers for all or a portion of a worker’s wages, offer a targeted strategy to help unemployed workers—including people with disabilities—enter or re-enter the labor force and bolster their credentials while alleviating hardship in the short term by providing immediate work-based income.

- Leverage early intervention. President Obama’s FY 2015 and FY 2016 budgets outlined several potential approaches to early invention and called for a demonstration project to evaluate their effectiveness. These or other approaches should be piloted to provide an evidence base for what works in this area.

- Reform asset limits. The ABLE Act, which allows people with disabilities to open special saving accounts without risking their eligibility in a number of government income support programs, represents an important step in the right direction, but it only helps a narrow subset of people with disabilities. To remove barriers to savings and ownership more broadly for workers with disabilities, Congress must take action to update Supplemental Security Income’s outdated asset limits, as the SSI Restoration Act would do. Additionally, myRA accounts—a new type of retirement savings accounts established in 2014—should be excluded from counting against asset limits in income support programs such as SSI and Medicaid.

- Ensure adequate affordable and accessible housing. Funding for public housing and the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program should be substantially increased to meet the needs of low-income people with disabilities. Additionally, policymakers should leverage federal and state funding sources to create and expand incentives for the inclusion of housing units for low-income people with disabilities, as well as compliance with accessibility standards, in new housing development and construction, such as through the Section 811 Supportive Housing for Persons with Disabilities program. Ensuring the availability of affordable, accessible housing would enable more people with disabilities to obtain safe and stable housing, secure steady employment, and live independently.

- Ensure adequate accessible transportation. Funding for Federal Transit Administration programs such as paratransit, the Section 5310 Transportation for Elderly Persons and Persons with Disabilities program, the United We Ride interagency initiative, and other vital transportation programs should be increased to enable more people with disabilities to enjoy basic mobility and take jobs that they currently cannot travel to and from without spending hours in transit.

This list is far from comprehensive, but it would go a long way toward removing barriers to employment and economic security for workers with disabilities.

Conclusion

Social Security Disability Insurance has been a core pillar of our nation’s Social Security system for close to six decades, offering critical protection to nearly all American workers and their families in the event of a life-changing disability or illness. The program’s eligibility criteria are restrictive and benefits are modest, but for those who receive benefits, it is nothing short of a lifeline, providing critical economic security when it is needed most. The recent budget deal includes several important provisions to strengthen Social Security Disability Insurance, including a modest, temporary reallocation that will prevent sharp across-the-board benefit cuts, as well as an array of measures to enhance program integrity. In addition to maintaining and strengthening Social Security Disability Insurance, Congress should enact policies to ensure that workers with disabilities have a fair shot at employment and economic security, such as paid leave.

Rebecca Vallas is the Director of Policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.