On March 1 sequestration—automatic across-the-board spending cuts—will take effect unless Congress acts to prevent it. These cuts, stemming from the so-called fiscal cliff deal that was made at the beginning of the year, have the potential to create overwhelming harm to Americans living in poverty. The poor, similar to most Americans, have been on the losing end of an unfair balancing act over the past couple of years—three-quarters of Congress’s deficit-reduction efforts have been in the form of spending cuts, while only one-quarter have come from increasing revenues through such means as increasing taxes on the wealthiest Americans.

A broad range of government functions would be impacted, including the small percentage (slightly more than 2 percent) of the federal budget that is dedicated to low-income assistance programs in areas such as housing, nutrition, child care, and energy. These “nondefense discretionary” dollars encompass the majority of the nation’s antipoverty programs and, unlike the extraordinarily limited number of “mandatory” or entitlement programs, their annual funding is at the whim of Congress, and participant access is not guaranteed. In 2013 spending on these low-income programs is likely to reach a decade low, and the sequester would cut another $41 billion from these vital programs.

This brief puts the potential harm of this lowered spending into context. Current budget cuts compound the serious challenges that were already impacting the nation’s efforts to reduce poverty. Welfare reform, which was passed in 1996 and marks the creation of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, was arguably the last significant chapter written by Congress on poverty. The impact was great, as welfare caseloads dropped by more than half after five years of implementation, with the program serving 2.5 million fewer families by 2002. Many mothers achieved positive results and entered the workforce, and poverty rates fell. But as time passed, the economy fluctuated and poverty rates ticked up, it became clear that there was significant unfinished business and more work to be done. Even before the Great Recession and the current budget crisis, single-mother poverty and childhood deep-poverty were on the rise and approaching pre-reform levels. Within this context, it’s hard to imagine what families will do and how the nation can reasonably reduce poverty should the federal government continue to slash budgets for critical programs.

Welfare reform and reductions in poverty

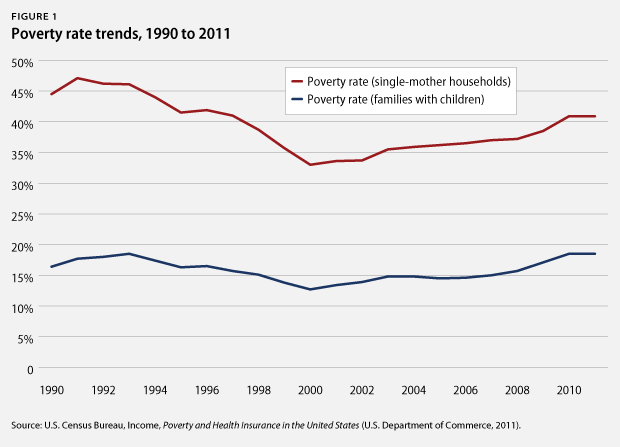

Initial implementation of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program coincided with reductions in poverty for families with children that mirrored poverty declines in female-headed families. Between 1996—the year welfare reform was passed—and 2000, the poverty rate for families with children dropped from 16.5 percent to 12.7 percent. (see Figure 1)

There were certainly elements of welfare reform that aided the poverty-rate decline—most notably, dramatic new investments in child care during the early years of the reform program. Between 1996 and 2001 funding for the federal Child Care Development Fund grew by nearly 500 percent, from $935 million to $4.6 billion. Additional child care dollars came from flexible federal funding sources such as the new Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, as well as from state government coffers. These investments made going to work possible for many welfare participants, many of whom were single mothers with young children—a group that has higher-than-average child care cost burdens.

Equally important was the intense focus put on connecting families to work opportunities under the new welfare reform program. The employment rate of those who had received welfare aid in the previous year increased from 27 percent in 1996 to 36 percent in 1999. Undoubtedly, placing intensive focus on how to get women into the workforce while also addressing some of their most significant employment barriers— including child care, transportation, and housing—helped many women and their children escape poverty.

But that’s not the entire story.

Other factors contributing to poverty reduction in the 1990s

During the 1990s there were at least two other significant factors influencing outcomes for families at the bottom of the economic ladder, suggesting that welfare reform was not solely responsible for important gains. Specifically:

- A vast economic expansion

- New progressive policies

Let’s look at each of these factors briefly in turn.

Vast economic expansion

The 1990s were defined by the longest economic expansion in U.S. history. Amid this strong economic growth, productivity increased and unemployment rates plummeted, remaining below 5.5 percent for more than two consecutive years. Because the economy was booming, people of color (who tend to have the highest unemployment rates) also shared in the prosperity.

New progressive policies

Former President Bill Clinton ushered in a wave of progressive policies in the early to mid-1990s that balanced the budget while also strengthening the incomes and job opportunities of the 99 percent. During the Clinton administration, the minimum wage was increased for the first time in five years. The earned income tax credit for low-income families was expanded in 1993, enabling 4.6 million people in low-income working families to rise out of poverty by 1998, shortly after the expansion was fully implemented. The federal government also invested in necessary infrastructure projects that created well-paying jobs for blue-collar workers.

In addition, the Clinton administration created the AmeriCorps national service program—a national network that engages Americans in various types of service for communities in need—and improved and expanded access to vital services such as the Head Start early childhood learning program, K–12 education, job training, and children’s nutrition and health care. These programs and initiatives, together with welfare reform, were key to moving families out of poverty.

Lingering poverty concerns post-welfare reform

Although welfare reform likely added to some other, more significant forces to help reduce poverty in the 1990s, the legislation suffered from a failure to focus on the goal of poverty reduction itself. It instead chose to focus on caseload reduction. The result is evident in certain trends that are worthy of concern, among them:

- Increased single-mother family poverty

- Working but poor mothers

- Rising deep poverty (below $9,062 for a family of three in 2011)

- “Disconnected mothers” with work barriers

- Lingering consequences of the Great Recession

Let’s unpack each of these problems in turn to see where reforms could ameliorate or reverse these specific problems with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

Increased single-mother family poverty

Households headed by single women—the primary group of Americans targeted by the old Aid to Families with Dependent Children program and the current Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program—continue to have persistently high rates of poverty. Currently, 41 percent of such families are poor, as compared to 19 percent of all American families. (see Figure 1) A further concern is a reversal in previous gains among these families—their poverty rate reached a low of 32.5 percent in 2000 but has steadily increased since then and now is approaching 42 percent, where it was the year before welfare reform was implemented.

The most recent decade also witnessed some decreases in women’s workforce-participation rates. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more single-mother households throughout the decade began reporting that they were not a part of the workforce during the year because they couldn’t find work, because they were going to school, or other reasons. As a consequence, their workforce-participation rates dropped during the 2007–2009 recession, suggesting that single mothers were struggling to find work and/or were using the downtime in the economy to gain more education to prepare for future work.

Mothers work but continue to be poor

The majority of poor single mothers do, however, participate in the labor force. There were 2.3 million women who were either working or actively searching for work in 2012, which represents 59 percent of the group. Since 1999, when the Census Bureau began publishing this data, this number hasn’t dropped below 1.8 million.

But if policymakers simply focus on whether women are in the workforce, with no concern about their job stability and level of earnings, the women (and their children) could continue to be poor. Progress requires improvements in areas that increase job stability and earnings such as access to paid leave and affordable child care.

Deep poverty rising

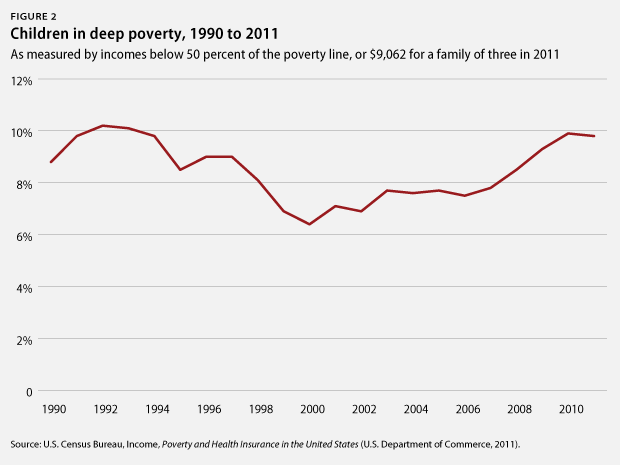

As with the general child-poverty rates, deep poverty—measured at 50 percent of the poverty line, or $9,062 for a family of three in 2011—among children dropped during the good economic times of the mid- to late 1990s, falling to 6.4 percent from 10.2 percent between 1992 and 2000. (see Figure 2) But in the 2000s these numbers began to trend upward even before the onset of the Great Recession. They now mirror numbers that existed before welfare reform.

By the end of 2008, the first full year of the Great Recession and the end of the George W. Bush administration, 8.5 percent of children lived in deep poverty. In 2011, as the nation continued down the path to recovery, that number was 9.8 percent. The data indicate that half of those in deep poverty are able to get out of it in a year’s time, suggesting that deep poverty is sometimes the result of temporary setbacks such as a parent’s loss of consistent work or a work-preventing illness. But there is much more still to be learned about this group at the very bottom of the economic ladder and the challenges they face.

“Disconnected mothers” with work barriers

Welfare reform’s emphasis on closing temporary assistance cases has been associated with increases in the number of “disconnected mothers,” or women living in poverty who are neither working nor receiving any temporary assistance. These women are poor because they face significant or sometimes multiple barriers to entering and remaining in the job market.

A Bureau of Labor Statistics study found that the two biggest reasons these women cite for being out of the workplace are the need to provide care for children and other family members and their own chronic illness or disability. Exact circumstances vary by family. Access to appropriate work supports such as safe and affordable child care will allow some of these women to return to work. Others may have a mental or physical condition that legitimately impairs their ability to obtain and maintain employment—such women may need help in accessing Social Security Income (for individuals with disabilities), which requires proof of a work-impairing disability in order to receive financial assistance.

The lingering consequences of the Great Recession

The two recessions that bookmark the past decade occurred after the welfare reform of 1996, and both recessions were accompanied by increases in poverty. During those periods, however, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program was much less responsive than other public benefits programs likely due to the program’s focus on caseload reduction. This emerging pattern was particularly striking during the Great Recession and its aftermath because women workers experienced unemployment rates from 2009 to 2012 that had not been seen since the mid-1980s26 (although they are improving), suggesting that many families and children may not be getting the additional help they need during even the worst of economic times.

Moving forward

Current efforts to reduce the deficit are not occurring in a political vacuum. Spending cuts, especially those targeting the poor, are a significant cause of concern, given the current state of poverty in America. In this post-welfare-reform era, many families continue to struggle—single-mother poverty and deep poverty have been on the rise over the past several years, and the ranks of the working poor have remained stubbornly large. These families are no longer getting much help from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, and they greatly depend on other services offered by the government. Cutting those services would produce dire circumstances for families and children. Further spending cuts must therefore be prevented as a part of sequestration and beyond. We must take still further steps—raising the nation’s revenues so that we can not only restore previous spending levels but also can ensure adequate funding for all services that are effectively helping to reduce poverty.

Finally, we have to examine what went wrong with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. Many of the problems we face in effectively addressing the issue of poverty are likely cropping up due to the failure of the welfare reform law to specifically focus on the goal of reducing poverty and to legislate a solid plan for how to reach that end. Such a plan would have taken better account of women facing significant or multiple barriers to employment, the likelihood of recession, and working women still being poor despite being employed.

Moving forward, legislators and administrative agencies should seek ways of changing course and rectifying these problems. They should also implement the comprehensive antipoverty reforms proposed by the Half in Ten campaign, which include expanding access to good jobs, living wages, paid leave, quality work supports, and strong safety net programs. (See our report, “The Right Choices to Cut Poverty and Restore Shared Prosperity: Half in Ten Report 2012,” published in November 2012.)

Joy Moses is a Senior Policy Analyst with the Poverty team at the Center for American Progress.