Melissa Boteach, Vice President of the Poverty to Prosperity Program, testified before the House Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Human Resources, November 17, 2015.

Thank you, Chairman Boustany, Ranking Member Doggett, and members of the subcommittee for the invitation to appear before you today. My name is Melissa Boteach, and I am the Vice President of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.

I am excited to join you today to talk about lessons the United States can take from other countries in terms of cutting poverty and promoting shared prosperity. There are a number of innovations across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, countries from which the United States can learn. In today’s testimony, I will underscore two main points:

- First, one of the most important lessons the United States can take from other advanced economies is that policies that improve basic labor standards, increase women’s labor force participation through stronger work-family policies, and strengthen social insurance have been critical for cutting poverty, mitigating inequality, and ensuring people can find and keep good jobs. I will provide specific examples of how other countries are using these policies to promote greater economic security and opportunity.

- Second, efforts to examine individual reforms in other countries cannot be divorced from this broader policy framework. It is important not to cherry-pick lessons from other countries absent the context of their stronger labor market protections, work-family policies, and more adequate income security programs for families who struggle to make ends meet. This lesson has important implications as Congress seeks to reform work and income supports in the United States.

Background

As I’m sure we can all agree, the surest pathway out of poverty is a well-paying job. Unfortunately, even as the employment numbers have improved in the past year, the poverty rate has declined only slowly because many Americans remain stuck with flat or declining wages, reduced hours, and inadequate labor protections. This is not a new trend. Except for a brief period in the late 1990s, over the past four decades, the gains from rising profits and productivity have gone mainly to those at the top of income ladder, while average Americans have seen their wages remain flat or even decline in real terms. In fact, the real hourly wage of a worker at the 10th percentile of the wage distribution in 2013 was 5.3 percent less than in 1979. By contrast, the real hourly wage of a worker at the 95th percentile grew by 40.6 percent over the same period.

Women’s labor force participation is an important tool to mitigate these trends and make all families better off. Nearly all of the rise in U.S. family income between 1970 and 2013 was due to women’s increased earnings, and according to the Council of Economic Advisers, if women’s labor force participation had not increased since 1970, “median family income would be about $13,000 less than what it is today.” Yet the United States is woefully behind its international counterparts in offering workplace policies that support women’s labor force participation, and a persistent gender wage gap means that women still earn, on average, only about 79 percent of what the average man makes, with significantly larger disparities for women of color. Closing this gender wage gap would cut the poverty rate for working women and their families in half, with fewer families needing to turn to the safety net in the first place.

Finally, even in good economic times, events such as a lost job or cutbacks in hours; divorce; disability; birth of a child; new caregiving responsibilities; and other life events are common triggers of a spell of poverty or hardship, underscoring that social insurance and assistance programs offer important protections from hardship that we all need. In fact, half of all Americans will experience at least one year of poverty or near-poverty at some point during their working years. Adding in those who experience unemployment or need to turn to the safety net for a year or more, that figure rises to four in five Americans.

These experiences are not unique to the United States. Across OECD nations, rising inequality presents a challenge, though it is more acute in the United States than in most other nations. Across OECD nations, people have to balance breadwinning and caregiving responsibilities and face income shocks such as job loss or onset of a disability.

Yet the United States consistently ranks near the bottom when compared with other advanced nations on comparable measures of poverty and child poverty. Moreover, despite rhetorical nods to the American Dream, a U.S. child born in the bottom income quintile of the income distribution has a lower probability of making it to the top income quintile than his or her counterparts in Denmark and Canada. The remainder of my testimony will explore policy differences that help explain these gaps and what the United States can learn from other nations in this regard.

What do other countries do to cut poverty and strengthen the middle class?

A key difference between the United States and other advanced nations is that other countries’ policies commit to supporting people in work through stronger labor standards; facilitating women’s labor force participation through policies such as paid family leave; and providing greater economic security through a more adequate social insurance system when work is unavailable, impossible, or pays too little to make ends meet.

Basic labor standards

First, other advanced nations tend to have stronger basic labor protections for workers. In the United States today, more than one in three people struggle to make ends meet, living below twice the federal poverty line. This is due in part to the fact that the United States tolerates lower levels of basic labor standards and worker rights than most other rich nations. Our minimum wage is a poverty wage, leaving a parent of two children who works full time in poverty. Low-wage workers are often subjected to scheduling practices that leave them no flexibility or certainty about their hours. And only about 7 percent of private-sector workers belong to a union. These trends have implications for usage of our safety net and families’ long-term economic mobility.

For example, “Nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of enrollments in America’s major public benefits programs are from working families.” In the fast food industry alone, more than half of front line workers are unable to support their families without nutrition or other assistance, and the cost of public assistance for these working families is nearly $7 billion per year. In contrast, raising the minimum wage to $12 per hour by 2020, as proposed in Rep. Bobby Scott (D-VA) and Sen. Patty Murray’s (D-WA) Raise the Wage Act, would save nearly $53 billion in expenditures on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, over the next 10 years.

In terms of scheduling practices, approximately half of low-wage workers report having minimal control over the timing of their work hours. In fact, in a study of low-skill, nonproduction jobs of 17 corporations in the hospitality, retail, transportation, and financial services industries, only three of the companies provided worker schedules more than one week in advance. When workers don’t know when or for how long they are working on a regular basis, it can wreak havoc on their ability to budget, take on a second job to help pay the bills, make child care and transportation arrangements, or move up the economic ladder by enrolling in education or training.

Finally, the barriers to joining a union in the United States limit workers’ ability to bargain collectively for better wages and health benefits, which puts additional pressure on Medicaid and other safety net programs that help low-wage workers make ends meet. Moreover, union membership has long-term positive consequences for children and families. Recently published research finds that “controlling for many factors, union membership is positively and significantly associated with marriage”—a relationship that is “largely explained by the increased income, regularity and stability of employment and fringe benefits that come with union membership.” And areas with higher union membership demonstrate more mobility for low-income children. Controlling for many factors, the relationship between union density and the mobility of low-income children is at least as strong as the relationship between mobility and high school dropout rates—a variable that is widely recognized as an important factor in a child’s long-term prospects.

Looking across the pond, in countries such as Denmark, collective agreements between trade unions and employer organizations are the norm, not the exception. In the United Kingdom, the national minimum wage, updated annually, is just more than $10 per hour, and the current conservative government is moving to increase it, with the goal of reaching 60 percent of median earnings by 2020. In addition to a much higher minimum wage, U.K. workers also have a guarantee of 28 days of paid time off each year and have stronger job security protections.

In terms of addressing scheduling standards, workers in the United Kingdom enjoy a “right to request” flexible and predictable schedules, and in turn, employers have an obligation to respond in a “reasonable manner,” including evaluating the pros and cons of the application, discussing the request with the employee, and providing an appeal process. The law is showing results. Surveys have found that the number of requests refused by employers dropped after passage of the legislation, and three years after the law was enacted, a survey in 2006 showed that there was increased availability of flexible working arrangements and a 7 percentage point increase in workplaces offering at least one of six flexible working arrangements to their employees. Already, this idea is gaining momentum stateside, with Vermont and San Francisco adopting right to request laws, and the Schedules That Work Act was introduced in the House and Senate to address these issues.

Work-family policies

A second area where the United States could learn from its neighbors is in the area of work-family balance and encouraging women’s labor force participation. Between 1990 and 2010, U.S. female labor force participation fell from 6th to 17th among 22 OECD countries. Research by Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn has found that 28 percent to 29 percent of this decrease could be explained by other countries’ expansion of family-friendly policies including parental leave and part-time work entitlements, whereas the United States guarantees no paid sick days and stands alone in failing to offer any form of paid family leave.

In contrast, the United Kingdom gives almost all workers a legal entitlement to paid sick days, provides paid family leave, and has a comparatively expansive system of pre-K and child care assistance. Denmark offers 12 months of paid family leave. And in Canada, parental leave constitutes up to 15 weeks of maternity benefits, plus an additional 35 weeks for parental care by either parent after the birth or adoption of a child.

In the United States, our lack of paid family leave has implications for usage of the safety net. In New Jersey, for example, where there is a state paid family leave program in place, a recent study conducted by Rutgers University found that women who use paid leave are significantly more likely to be working 9 to 12 months after a child’s birth than those who do not take any leave. Moreover, women in New Jersey taking paid leave reported wage increases from prebirth to postbirth and were 39 percent less likely to receive public assistance and 40 percent less likely to receive assistance from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps, in the year after the child’s birth, compared with women who did not take leave.

More adequate social insurance

Finally, other OECD countries tend to have significantly more adequate social insurance regimes that the United States for the messy ups and down of life such as a health crisis, unemployment, birth of a child, or onset of a disability. I will briefly review several examples below.

Health insurance

Nearly all advanced nations offer universal health care coverage. In contrast, in the United States, 19 states have refused to implement the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, leaving millions of low-income adults without access to care and unable to purchase insurance on the health care exchanges.

Child benefits

Another common thread across many rich nations is a child benefit that significantly reduces child poverty. For example, the new government is Canada is slated to significantly expand its child benefit for low- and moderate-income families, and the United Kingdom provides a family allowance to all low- and middle-income families with children through its Child Benefit and Child Tax Credit.

The United States has a Child Tax Credit, or CTC, which offers up to $1,000 per child. The refundable portion phases in at a rate of 15 cents per dollar starting at $3,000 of earnings, so that a family with two children earning a full-time minimum wage salary would receive approximately $1,800 instead of the full $2,000. However, if Congress fails to act to make permanent the 2009 provisions of the CTC—slated to expire in 2017—that same working family would only receive $72 from the CTC moving forward. The CTC is an important anti-poverty tool in the United States, but it could be strengthened by: ensuring that the full credit reaches all low- and moderate-income families; indexing the credit to inflation so that it keeps pace with the rising cost of childrearing; and adding a Young Child Tax Credit of $1,500 for children under age 3, available in monthly installments, in recognition of the particular squeeze that parents of young children face and the elevated importance of income in the early years for children’s long-term outcomes.

Unemployment insurance

While the United States’ unemployment insurance, or UI, system has played an important role in mitigating poverty and providing macroeconomic stabilization, compared with other nations:

[T]he United States has one of the least generous UI systems in the developed world. Jobless benefit programs in European nations and most other OECD member countries (sic) programs generally serve significantly larger shares of their unemployed populations, provide benefits that replace a significantly higher share of worker’s previous earnings, and offer benefits for far longer durations than the United States’ UI program. Additionally, most other countries require employers to offer severance pay, which comes in addition to jobless benefits.

For example, the vast majority of workers in Denmark are guaranteed two years of unemployment insurance at a 90 percent wage replacement, and in addition to its contributory insurance, the United Kingdom guarantees means-tested unemployment assistance to low-income people who are unemployed.

In the United States, our UI system “protects workers and their families against hardship in the event of job loss by temporarily replacing a portion of their lost wages while they seek reemployment. … UI is a federal-state program with minimal federal requirements and tremendous state flexibility. … Historically states have had maximum benefit durations of 26 weeks or longer. However, in a recent trend, eight states have reduced the number of weeks of benefits available to fewer than 26 weeks, with Florida cutting off benefits at just 14 weeks.

“The recent economic downturn offers a stark reminder of the critical importance of the UI system. While benefits are modest, averaging just over $300 per week and replacing 46 percent of wages for the typical worker, UI protected more than 5 million Americans from poverty in 2009, when unemployment was at historic heights. In addition to mitigating poverty and hardship, UI also functions as a powerful macroeconomic stabilizer during recessions, by putting dollars in the pockets of hard-hit unemployed workers who will then go out and spend them in their local communities.”

Yet as “[e]ffective as UI is, it fails to reach many unemployed workers in their time of need. As of December 2014, the UI recipiency rate—or the share of jobless workers receiving UI benefits—fell to an historic low of 23.1 percent.”

Disability benefits

The United States offers “modest but vital” disability benefits in a regime in which it is incredibly difficult to qualify for aid. In fact, the United States has the strictest disability standard in the developed world, and our Social Security Disability Insurance, or SSDI, and Supplemental Security Income, or SSI, programs include strong work incentives. SSDI benefits are “modest, typically replacing half or less of a worker’s earnings.” The average SSDI benefit for disabled workers “in 2015 is about $1,165 per month—not far above the federal poverty level for an individual.” SSDI benefits are “so modest that many beneficiaries struggle to make ends meet; nearly one in five, or about 1.6 million, disabled-worker beneficiaries live in poverty.” But without SSDI, “this figure would more than double, and more than 4 million beneficiaries would be poor.” SSI benefits are even more meager, at a maximum of $733 per month in 2015, “just three-quarters of the federal poverty line for an individual.”

“As long projected by Social Security’s actuaries, the number of workers receiving Disability Insurance has increased over time, due mostly to demographic and labor-market shifts. According to recent analysis by Social Security Administration researchers, the growth in the Disability Insurance program between 1972 and 2008 is due almost entirely (90 percent) to the Baby Boomers aging into the high-disability years of their 50s and 60s, the rise in women’s labor-force participation, and population growth. The increase in the Social Security retirement age has been another significant factor. Importantly, as the Baby Boomers have begun to age into retirement, the program’s growth has already leveled off” to its lowest level in 30 years “and is projected to decline further in the coming years as Boomers continue to retire.”

Efforts to point to disability reform in countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the Netherlands as models for the United States ignore the fact that even after these reforms, these countries still have higher recipiency rates, more adequate benefits, and spend more as a share of gross domestic product, or GDP, on their programs than we do. Rather, by emulating other countries’ policies—such as paid leave, better access to long-term services and supports, and universal health coverage—we could build upon our current system and give workers with disabilities a fairer shot at economic opportunity.

A note on the ‘submerged welfare state’

While other OECD countries tend to spend more as a share of GDP in terms of public social expenditures, looking at net social expenditures, which include expenditures subsidized through the tax code—such as employer-subsidized health care for higher-income families—the United States actually spends more as a share of GDP than many other OECD countries. This “submerged welfare state” underscores that social expenditures do not just benefit struggling families but also extend up to include many wealthy families in the United States. Thus, as we seek to discuss welfare reforms, it is important to note that while the United States is relatively ungenerous when it comes to helping lower-income families, looking at our net social expenditures, we are considerably more generous to upper-income families than other nations.

More broadly, as we discuss welfare reform, it is important to consider reform of corporate welfare and tax expenditures that primarily benefit the wealthy. Although the top 0.1 percent holds as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent in the United States, a typical person in the top 0.1 percent received $33,391 last year from the largest of these federal tax programs, while an American in the bottom 20 percent received about $77. It is important to keep this context in mind as Congress considers tax and budget decisions regarding low-income families.

The dangers of cherry-picking lessons

While there are many important lessons to take from other nation’s policies, there is a danger in cherry-picking reforms from other countries that feed into their preconceived notion that block granting and cutting core income security programs are the best paths forward. These policy lessons are often divorced from the broader framework these countries have in place with regards to labor rights, work-family balance, and social insurance.

For example, some have pointed to the Universal Credit in the United Kingdom, a policy that combines several means-tested benefits into one payment to families, as the inspiration for efforts to consolidate and block-grant multiple anti-poverty programs in the United States. Yet the Universal Credit bears little resemblance to these proposals and is situated in a much different policy regime, as noted above, with higher wages, stronger work-family policies, and more adequate income security programs.

For one thing, the United Kingdom’s Universal Credit is structured as a legal entitlement—meaning that all eligible low-income people have a right to receive it—and one that is administered centrally by a single government agency. In contrast, block grant proposals here in the United States limit the extent to which eligible families can access needed help. They also decentralize administration of funds to states, which have a long history of diverting those funds away from the core purposes of the block grant.

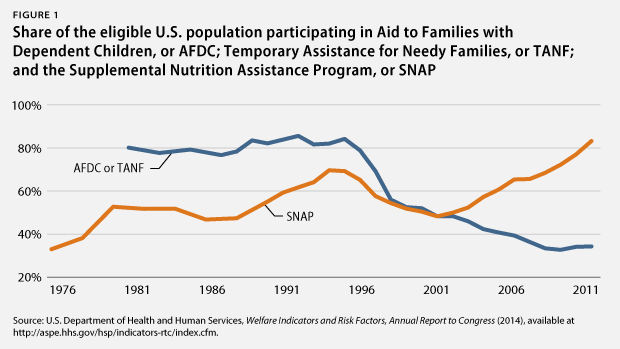

For example, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, which some lift up as a model for other programs, has failed to respond to the recession or the increase in child poverty in recent years, “rising by just 16 percent between the onset of the recession and December 2010, while the number of unemployed workers rose by 88 percent during the same period.” The block grant has lost approximately one-third of its value since 1996, and even more in states that used to receive supplemental grants. Whereas it used to serve approximately two-thirds of poor families with children, today the program only serves about one in four poor families with children—and in many states, it serves far fewer. “In comparison, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program is highly effective at reaching struggling individuals and families, with 8 in 10 eligible households receiving needed nutrition assistance.”

Moreover, states have little to no accountability for spending the funds toward TANF’s core purposes, with recent data showing that states only spent an average of 8 percent of the block grant on work-related activities and less than half of the block grant on “core purposes.”

“In contrast, in programs such as SNAP, approximately 95 percent of program dollars go to helping struggling families purchase food. The error rate for SNAP is among the lowest of all government programs, with fewer than 1 percent of SNAP benefits going to households that do not meet the program’s criteria. Research also shows that SNAP boosts health, educational, and employment outcomes in the long term. Rather than model other programs after TANF, policymakers should be seeking ways to boost the program’s effectiveness and transparency to ensure that dollars are going toward providing income and employment support to struggling families.” Indeed, as Ron Haskins, a long-time former Republican staffer and one of the chief architects of TANF, said recently about the program, “States did not uphold their end of the bargain. So why do something like this again?”

Another reason the Universal Credit offers a poor example for the United States is that one of the main problems the United Kingdom is trying to address—financial penalties for work—is far less of an issue in the United States, in part due to the design of our Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC—which kicks in at the first dollar of earnings. In fact, this is one area where other countries seeking to address work disincentives caused by loss of benefits can learn from the United States.

Together, the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits reward work and lifted approximately 10 million people out of poverty last year. Not only do these credits improve the short-term well-being of children through mitigating poverty, but they also improve long-term education outcomes for children.

As Congress debates tax extenders, it should protect and build upon the EITC’s bipartisan success. In fact, Congress should not make any provision permanent for businesses without making permanent provisions of the EITC and CTC set to expire in 2017. Allowing these key parts of the credits to expire would push approximately 16 million people, including 8 million children, into or more deeply into poverty. Moreover, there is growing bipartisan support, from House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) to President Obama, for expanding the EITC for childless adults, the only group our country currently taxes more deeply into poverty.

Regarding concerns about the U.S. safety net penalizing work, the biggest issue in this regard is states that have not yet expanded Medicaid. In these 19 states, a family who earns too much to qualify for traditional Medicaid but not enough to qualify for subsidies to purchase on the exchanges falls into a health coverage gap. The answer to this, rather than consolidation and block-granting of programs, is for all states to expand Medicaid.

Policy implications and conclusion

How do the lessons from other countries translate into policy implications for the United States?

First, it is important not to go backward. In general, the OECD nations with the best outcomes have increased the share of their GDP they commit to public social insurance and investments over the past two decades. While many OECD nations have increased their investments in active labor market policies, these same nations continue to provide a more adequate floor than we have in the United States. And what the United States does have in place, while in need of improvement, plays a significant role in mitigating poverty and hardship. In fact, without the safety net we currently have in this country, poverty rates would be nearly twice as high. Rather than turn to TANF as a model for other safety net programs, we should protect and strengthen programs such as SNAP, tax credits for working families, and Medicaid.

Second, while the United States doesn’t need to emulate the exact policies of our OECD counterparts, we can customize uniquely American solutions that move toward the same values of rewarding and valuing work through strong labor standards, encouraging women’s labor force participation through improved work-family policies, and bolstering our social insurance system to better account for the messy ups and downs of life. This includes policies such as raising the minimum wage; making permanent the 2009 provisions of the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits slated to expire in 2017 and expanding the EITC for childless adults; enacting universal paid family and medical leave and paid sick days; enacting the right to request a flexible and predictable work schedule; investing in child care and early education; expanding Medicaid; strengthening our unemployment insurance system; enabling all low- and moderate-income families to claim the full CTC; and adding on a Young Child Tax Credit for families with children under age 3 to account for the importance that these early years play in children’s long-term outcomes.

Such policies would not only cut poverty and economic mobility through better employment, educational, and health outcomes; in many cases, they also would reduce the need of families to turn to the safety net in the first place because policies that bolster wages, improve working conditions, and offer work supports such as child care and health insurance increase the likelihood that families can support themselves in the labor market.

These ideas noted above are not just international standards. Policies such as raising the minimum wage and enacting paid family leave command the support of the vast majority of Americans across the ideological spectrum. Efforts to stymie the enactment of such policies ignore evidence from both abroad and from U.S. states that these initiatives are effective in cutting poverty and boosting middle-class security.

Melissa Boteach is the Vice President of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.