As the United States’ COVID-19 crisis stretches into the summer months, millions of workers continue to risk their lives to do the jobs necessary for the country to function. Workers categorized as essential vary widely by location and perform a diverse set of jobs; they are doctors, nurses, firefighters, grocery workers, postal carriers, funeral attendants, delivery drivers, farmworkers, and more. Despite a national rhetoric that glorifies essential workers as heroes and saviors, many who must continue to work do so because they can’t afford to lose their paychecks. Now, a new Center for American Progress analysis shows that workers in essential roles are also more likely to have needed federal assistance such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to get by; more than 5.5 million essential workers relied on the program at some point in 2018, according to 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) data.

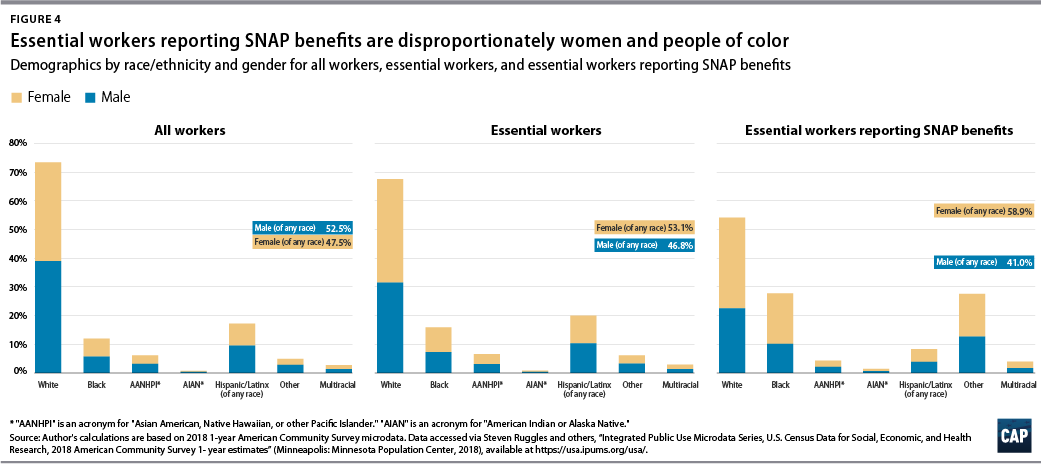

What is finally being recognized as essential work includes roles that have long been underpaid and undervalued. One analysis estimates that at least 13 million essential workers did not earn a wage of at least $15 an hour in 2018. More than half of the essential workforce are women; they are disproportionately people of color as well. These workers are also more likely to live at or slightly above the federal poverty line—a measure that already underestimates economic deprivation across the country.

At just an average of $1.40 per meal per person, SNAP benefits don’t even always last the month—but they still provide critical help for families struggling to make ends meet. As workers organize, strike, and demand the protections they have always deserved, Congress must ensure that essential workers have access to increased wages, hazard pay, personal protective equipment, paid leave, safe working conditions, and more. Labor protections and a comprehensive safety net go hand in hand to ensure that essential workers and their families are able to meet their most basic needs—both in the current public health emergency and beyond.

Strengthening a program such as SNAP in this moment would help not only low-income families and people who have lost jobs and hours, but also the millions of essential workers who use SNAP to keep themselves and their families fed.

Who are America’s essential workers?

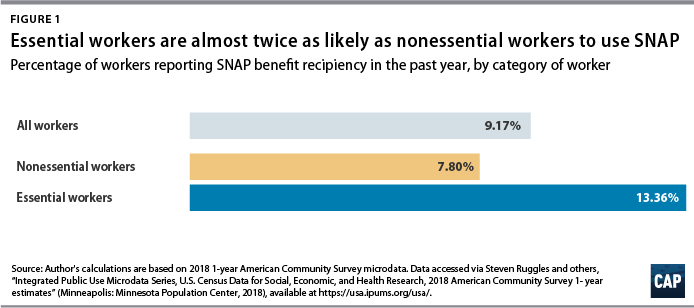

A CAP analysis of 2018 ACS data finds that there are slightly less than 42 million essential workers in the United States. (Estimates define “essential” using ACS industry and occupational codes and federal guidance. For more information, please refer to the Methodology and the downloadable tables containing lists of industries and occupations categorized as “essential.”) More than 5.5 million, or 13.36 percent, of them needed SNAP benefits at some point during 2018. That’s almost twice the rate of SNAP recipiency for nonessential workers, 7.8 percent of whom utilized the program. For all U.S. workers, defined as those who reported working in the past year, that percentage was 9.17 percent.

This analysis looks at those who reported both working in the past year and receiving SNAP benefits in that same time period, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that they happened simultaneously. Some essential workers may have used the program to fill the gap between poverty wages and a livable income. Others may turn to SNAP for a number of other reasons, such as because they’ve lost income due to cut hours, experienced income volatility month to month, are in between jobs or otherwise unable to work.

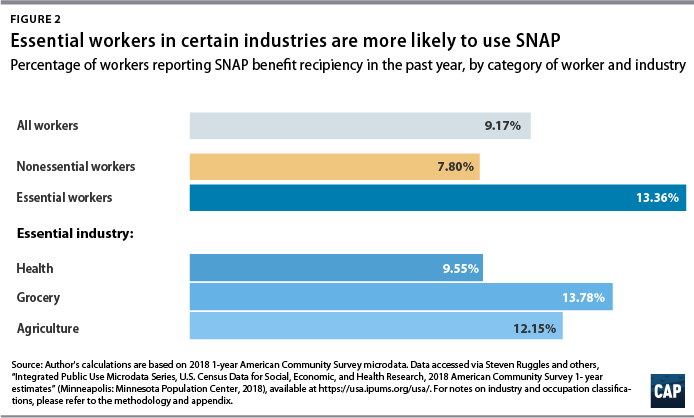

That millions of workers must turn to federal assistance to put food on the table is already an indictment of America’s weak labor laws and reliance on poverty wages. This analysis finds that the workers whom Americans rely on to keep them safe, healthy, and fed must often rely on SNAP to meet those same needs. Workers in the health, agriculture, and grocery industries all report disproportionately high SNAP recipiency rates when compared with workers overall. Almost one-third of essential workers who used SNAP at some point in the year worked in the food and restaurant sector, an industry that is also facing record closures and layoffs—even when classified as essential. And about 1 in 6 farmworkers, many of whom must endure dangerous conditions, had to turn to SNAP to put food on their own tables.

SNAP recipiency rates for essential workers vary by race, ethnicity, and gender

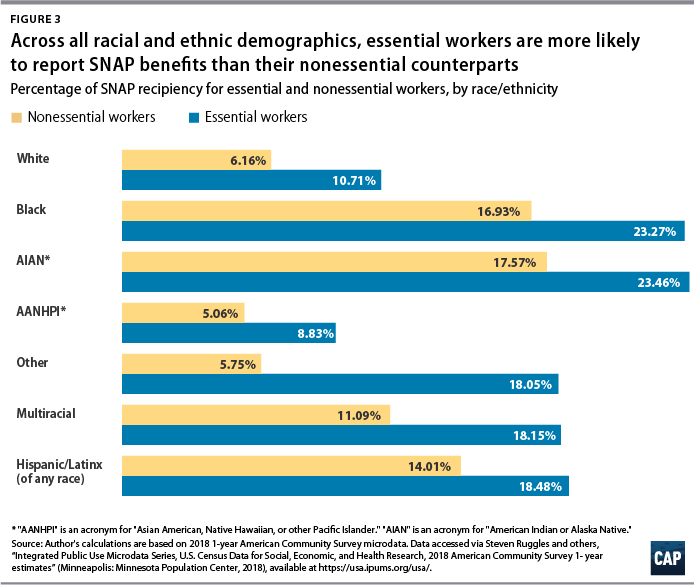

SNAP recipiency rates for essential workers vary across racial and ethnic demographics and are higher than rates for their nonessential counterparts. (see Figure 3) So while almost 17 percent of Black nonessential workers reported SNAP benefits, 23.27 percent of Black essential workers reported using the program. By contrast, 6 percent of white nonessential workers and 10.7 percent of white essential workers reported SNAP benefits.

Although Black workers make up about 12 percent of the general workforce, they are nearly 16 percent of the essential workforce. More than one-quarter of essential workers who use SNAP are Black, and about 27 percent of essential workers who used SNAP benefits were Hispanic or Latinx (of any race).

These numbers become even more pronounced when looking at essential workers who are women of color—a demographic already facing disproportionate economic impacts from the pandemic. Black women, for example, make up almost 9 percent of essential workers, but they represent 17.6 percent of essential workers who have relied on SNAP.

These numbers become even more pronounced when looking at essential workers who are women of color—a demographic already facing disproportionate economic impacts from the pandemic. Black women, for example, make up almost 9 percent of essential workers, but they represent 17.6 percent of essential workers who have relied on SNAP.

These disparities reflect a long-known truth: People of color and women—and women of color most of all—are disproportionately represented in jobs that have low pay and insufficient workplace protections and benefits. The stratification didn’t happen by chance; it’s a direct result of systemic inequities that have pushed those with the least economic and political power to the margins, in jobs that, by virtue of who is performing them, are underpaid and undervalued in almost every way possible. Congress must make longer-term, structural changes to dismantle those inequalities, but these workers also need immediate help during the crisis facing the country now; strengthening SNAP is just one way to provide that aid.

Conclusion

America is experiencing record unemployment and skyrocketing food insecurity, but receiving a paycheck isn’t always enough to prevent hunger. Front-line workers need bold, long-term policy actions to ensure they can work in safe conditions with more than adequate pay and benefits—and Congress needs to fight for that in the next legislative package. But legislative action to strengthen social safety net programs such as SNAP is also critical. In the short term, SNAP has proven effective at quickly getting aid to those who need it most, when they need it most—including the workers whom America is relying on to keep it functioning in the midst of a crisis.

Areeba Haider is a research assistant for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Connor Maxwell, Nicole Prchal Svajlenka, Diana Boesch, Zoe Willingham, s.e. smith, and David Ballard for their contributions to this analysis, as well as Justin Schweitzer and Jaboa Lake for fact-checking.

Methodology

The findings in this column are based on CAP analysis of 2018 one-year American Community Survey data, accessed via IPUMS.

For this analysis, the author defines an essential worker as one who worked in both an essential industry and an essential occupation in the last year, per ACS data. Classification as an “essential” industry or occupation was determined using the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s “Guidance on the Essential Critical Infrastructure Workforce”; the Brookings Institution’s “Front Line Workers—Industry Appendix”; the Center for Economic and Policy Research’s demographic profile of workers in front-line industries; and industry and occupation analysis provided by Nicole Prchal Svajlenka, associate director for research on the Immigration Policy team at CAP. A full list of selected industries and occupations can be found in the downloadable spreadsheet linked below.

Because state definitions of essential workers vary—and in the absence of a clear federal directive—this analysis of essential workers is necessarily limited. It does not include those who continue to work in an essential industry if their particular occupation is not also categorized as “essential”—for example, a human resources manager in the air transportation industry. It also excludes those who have an essential job in an industry that is not broadly categorized as such and workers outside those essential categories, even if they might be going back to work as their states reopen.

Click here to download the lists of occupations and industries categorized as essential for this analysis, along with corresponding ACS codes.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.