Just a few weeks into the 116th Congress, Democrats’ takeover of the House of Representatives has already exposed the huge gulf between what American voters want and what the previous House leadership and the Trump administration have thrust upon them in recent years. Congressional Democrats’ bold agenda—such as higher taxes on the rich, universal health care, and expanding Social Security—has strong support not just among progressives but also across party lines. This popularity is a direct rebuke to Trump’s and his congressional colleagues’ massive 2017 tax giveaway to the wealthy and corporations; Trump’s ongoing efforts to sabotage the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid; and Trump’s and congressional Republicans’ continued efforts to cut Social Security.

Perhaps nowhere is the gulf between voters’ wishes and the policies Trump and his colleagues in Congress are pursuing greater than when it comes to Social Security—a program that voters overwhelmingly want to see expanded rather than cut. A 2017 Pew Research Center poll found that 95 percent of Democrats and 86 percent of Republicans preferred to maintain or expand Social Security. Yet, despite promising not to cut Social Security on the campaign trail, President Donald Trump’s fiscal year 2019 budget would have slashed $72 billion from the program—cruelly targeting people with disabilities—over the coming decade. And Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and then-House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) didn’t even wait until the ink was dry on their $2 trillion tax giveaway to begin insisting that everyday Americans face cuts to Social Security to pay for their deficit-busting tax bill.

Fortunately, American voters finally have champions in the growing chorus of Democratic lawmakers calling for expanding Social Security. Their approach fits seamlessly into the growing calls for higher taxes on the wealthy from congressional leaders and 2020 presidential contenders: It pairs benefit increases with commonsense revenue raisers such as lifting the payroll tax cap so that higher earners pay into Social Security all year, just like other workers do. This is a move that more than two-thirds of Americans support and reflects the common desire of both voters and progressive policymakers to tackle the nation’s sky-high inequality by putting everyday workers and families—not the uber-rich—first.

Rising inequality has not only threatened working families’ economic security—making Social Security’s modest benefits all the more critical—it has also actively damaged Social Security’s financial outlook. This analysis updates earlier CAP analyses to illustrate how much rising inequality has harmed Social Security’s finances since 1983—the last time major changes were made to the program. (see earlier versions for methodology) We first show how policymakers’ failure to address rising inequality benefits rich Americans, including millionaire and billionaire earners as well as President Trump. Second, we show how Social Security’s combined retirement and disability trust funds would have contained $1.4 trillion more by the end of 2017 if policymakers had kept the payroll tax fixed at 90 percent of earnings rather than letting an increasing share of rich Americans’ income go untaxed every year. Finally, we show that the trust funds’ assets would have been $570 billion greater by the end of 2017 if the average worker’s pay had grown in step with their productivity since 1983 instead of the paltry pay gains they actually experienced.

A second Valentine’s Day for millionaire and billionaire earners, including President Trump

The vast majority of working Americans will contribute to Social Security with every paycheck they earn. This includes even the lowest-paid workers—those who earn the federal minimum wage of just $7.25 per hour—who haven’t seen a raise in 10 years. But, ironically, it’s America’s highest earners—those who can most readily afford to contribute—whom policymakers have chosen to give a break. In 2019, every dollar they earn above the payroll tax cap of $132,900 will escape Social Security payroll taxes entirely.

As a result, while roughly 94 percent of workers contributed the full 12.4 percent of their annual earnings toward Social Security taxes in recent years—with half paid by the worker and half by their employer—America’s highest earners pay only a small share of their income. That includes President Trump who—if his claims about his 2016 income are true—contributed a mere 0.002 percent of his income to Social Security in 2016. In other words, Trump pocketed an additional $86 million simply because policymakers have not required higher earners such as him to contribute payroll taxes at the same rate as everyone else, including the nation’s lowest-paid workers. It would take nearly 22,000 additional workers earning the median salary to make up for the contributions he avoids.

February 18 is Valentine’s Day for millionaires, the day when last of the millionaires in the United States will stop contributing to Social Security for the entirety of 2019.

Policymakers’ sweetheart deal for high earners means the richest Americans celebrate their own special holiday early in the year. February 18 is Valentine’s Day for millionaires, the day when last of the millionaires in the United States will stop contributing to Social Security for the entirety of 2019. The richer they are, the earlier their gift arrives: Based on his 2016 income, President Trump ceased contributing to Social Security just 40 minutes into the new year. Similarly, for many in Trump’s rich donor circles and in his “$2 billion Cabinet,” time spent paying into Social Security is measured in just minutes or days.

This gift comes on the cusp of tax season—when the richest Americans will reap their first year of massive benefits from the last Congress’ $2 trillion tax law. The tax law’s handouts underscore how skyrocketing salaries capture only part of the inequality picture. In addition to earnings inequality, inequality has grown on the basis of wealth as well as the capital income that, while almost negligible for the vast majority of Americans, makes up more than one-quarter of the top 1 percent’s income.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the inequality equation, a huge swath of everyday Americans—more than 4 in 10—are struggling to afford the even basics such as food, housing, health care, and transportation in today’s economy. For the many working families living paycheck to paycheck, Social Security’s modest benefits are more important than ever as a bedrock of economic security in the event of retirement or disability.

3 ways income inequality harms Social Security’s finances

For American workers and their families, Social Security has provided the foundation of economic security for more than 80 years and counting. In 2018, roughly 63 million Americans received retirement, disability, or survivor benefits through the Social Security system. The program’s modest benefits are nothing short of vital—particularly for women and workers of color—making up at least 50 percent of family income for more than half of seniors and roughly 8 in 10 workers with disabilities in recent years.

With everyday Americans facing a looming retirement crisis; flat pay and a diminishing minimum wage; and rapidly rising costs for a basic middle-class lifestyle, Social Security’s benefits will become even more important in future years. However, a small slice of high-income workers are pulling far away from these hardships and challenges, as their earnings disproportionately increase compared to those of average workers. In 2016, the top 1 percent of workers captured nearly 13 percent of all earnings in the United States, bringing home average salaries worth more than $600,000—nearly 20 times what a worker in the bottom 90 percent earned.

Every year, America’s rising inequality leaves everyday working families further behind. But compounding this hardship is the fact that inequality is also hurting the financial outlook of the key program these families will depend on when they reach retirement or experience a disability. Here are three main ways that inequality is damaging Social Security’s finances.

1. Weak wage growth for everyday workers has dampened payroll tax revenues

Starting in the early 1970s, workers’ average pay ceased to keep pace with their productivity, as it had in the previous decades. Instead, workers’ pay grew slowly—if at all—while the gains from their output were directed toward the pockets of CEOs and corporate profits.

Slow wage growth for everyday workers causes revenues flowing into Social Security’s trust funds from payroll taxes to grow more slowly than if wages had risen faster. At the same time, it also jeopardizes families’ economic security and makes it harder for them to save, which makes Social Security’s modest benefits all the more important when workers reach retirement or experience a disability.

2. An increasing share of rich Americans’ earnings escapes taxation

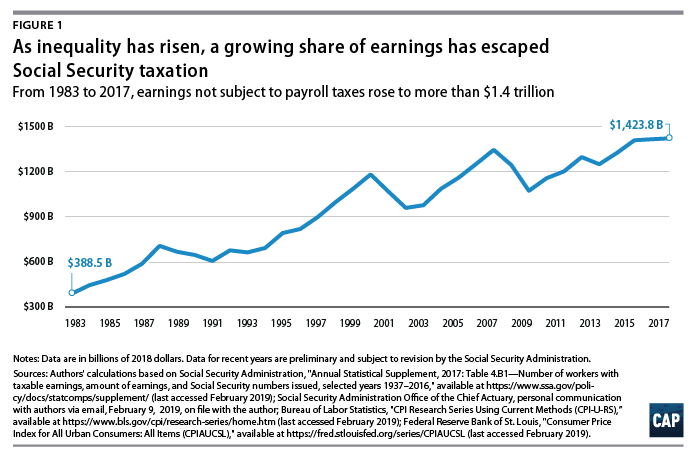

As the pay of the richest Americans has increasingly pulled away from that of the average worker, a greater share of total earnings has become concentrated above the payroll tax cap. Any earnings that exceed this cap—$132,000 in 2019—are exempted from Social Security taxation. That means Social Security’s revenues suffer when pay becomes more concentrated in the hands of the rich compared to revenues if the distribution of pay were more equal. Although the payroll tax cap tends to rise gradually every year because it is linked to the Social Security Administration’s national average wage index, earnings for workers at the top have risen much faster than the index. As a result, only 83.4 percent of total earnings were subject to Social Security’s payroll taxes in 2017, down from 90 percent in 1983—the last time Social Security saw a major reform. (see Figure 1) As a result, in recent years, roughly $1.4 trillion escaped Social Security taxation.

Due to this growing gap between the payroll tax cap and earnings at the top, high earners— including the nearly 150,000 American millionaire and billionaire earners—stop contributing to Social Security early in the year, while the average American worker contributes all year long. In 2019, the last millionaire—with earnings of exactly $1,000,000—will finish contributing on February 18, just 49 days into the year.

3. The gap between the bottom and the middle has widened

While economic insecurity is widespread in today’s economy—with more than 4 in 10 Americans struggling to afford basics such as housing, food, and health care—rising inequality has been particularly harmful for the lowest-income workers and families. This include workers making the federal minimum wage of $7.25, which Congress has refused to raise for a decade. As a result, since 2009, a full-time, year-round worker earning $7.25 per hour has effectively lost $13,330—nearly a full year’s salary—to inflation. From 1979 to 2017, the lowest-earning 10 percent of workers saw slower wage growth than any other decile of earners and less than half the growth of the middle decile. Recent research shows that failure to raise the federal minimum wage has increased poverty and hardship and exacerbated the retirement crisis facing lower-wage workers, making Social Security’s benefits all the more critical.

In addition to jeopardizing workers’ ability to make ends meet, the rise of the low-wage economy also strains Social Security’s finances, making it costlier for the program to provide retirement benefits to workers. This is a result of two things. First, as indicated above, Social Security’s payroll taxes are levied on the basis of wages, so lower wages and slower wage growth mean less money flowing into the trust funds than if wages were higher and rising with productivity growth. Second, because Social Security’s benefits are progressive—meaning they replace a greater share of lifetime earnings for lower-wage workers than higher-wage workers when workers reach retirement or experience a disability—benefits disproportionately rise when wages stagnate for low-wage workers. In other words, Social Security’s benefit obligations grow more quickly compared to payroll tax revenue when inequality beneath the payroll tax cap widens than if the gap between the bottom and the middle were to remain fixed.

To what extent has rising inequality already hurt Social Security?

The following analysis assesses how much larger Social Security’s combined trust funds would be today if not for the rise in earnings inequality since 1983—the last time the Social Security program underwent substantial reforms. To do so, we revised two simulations originally described in a 2015 CAP analysis—updating them to 2017, the most recent year for which complete data are available. The first simulation estimates how much greater the trust funds’ assets would be if policymakers had ensured that 90 percent of earnings remained subject to Social Security’s payroll taxes in every year from 1983 to 2017 rather than shrinking to 83.4 percent. The second simulation estimates how much greater assets would be if workers’ wages had grown at the same pace as productivity since 1983 instead of the anemic growth wages actually experienced. These two simulations represent a conservative assessment of how rising inequality has affected Social Security’s financial outlook. (see full methodology in CAP’s 2015 analysis)

We estimate that if Social Security’s taxable wage base had remained at 90 percent of earnings since 1983, the assets in the combined trust funds would have been $1.4 trillion greater at the end of 2017. This alone would close nearly 11 percent of Social Security’s anticipated 75-year funding shortfall. Furthermore, we estimate that if the average worker’s wages had kept pace with their productivity since 1983, the assets in the combined trust funds would have been $570 billion greater at the end of 2017.

Conclusion

Policymakers are finally catching up in growing numbers to Americans’ strong, long-standing, cross-party support of the Social Security program. In the new Congress, progressive lawmakers are heeding the people’s call for both expanding the program’s benefits and curbing the pernicious inequality that has damaged its finances. At the same time, the policy solutions that would help achieve these goals—such as raising or eliminating the payroll tax cap—are the same ones that address the growing public demands for higher taxes on the wealthiest Americans so that they pay their fair share.

As a candidate, President Trump played on Americans’ overwhelming support for Social Security when he promised not to cut the program. If Trump were serious about this promise—as with the many other vows he made to America’s “forgotten men and women” whose future economic security hinges so heavily on this vital program—Trump and lawmakers aligned with him would listen to the American people and join these efforts to strengthen and expand Social Security.

Rachel West is the director of research for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.