This column contains a correction.

On April 30, Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) and Rep. Bobby Scott (D-VA) are expected to announce a new proposal to raise the federal minimum wage to $12 per hour by 2020. The Raise the Wage Act would phase the new minimum wage in slowly, beginning with $8 per hour in 2016 and increasing in single-dollar increments over the following four years. Starting in 2020, the minimum wage would be indexed to the median hourly wage* to protect its value in future years. In addition, Murray and Scott’s proposal would slowly phase out the so-called tipped minimum wage, which has been stuck at $2.13 since 1991.

It has been six years since the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour was last raised; each year, its purchasing power falls as price levels rise. Despite the success of recent campaigns at the state and—increasingly—local levels, 21 states have remained bound by $7.25 since 2009.

If it were passed, the most important outcome of the Murray-Scott bill would be a long-overdue raise for struggling workers. A large body of economic research has explored the benefits of minimum-wage increases: Past increases in federal, state, and local minimum wages have increased earnings and reduced poverty among low-wage working families without leading to job loss.

These benefits have become increasingly important in the aftermath the Great Recession. The jobs that have returned during the recent recovery are disproportionately concentrated in low-paying sectors such as retail services. Furthermore, a large and increasing percentage of today’s low-wage workers are not teenagers or secondary earners; instead, they are adults with significant work experience and parents raising young children. The stagnant federal minimum wage disproportionately affects women and workers of color, frustrating efforts to address pay inequity and income inequality.

Working families, however, are not the only group that would benefit from higher minimum wages. Raising the minimum wage would lead to significant savings for all American taxpayers.

America’s current minimum wage is a poverty wage: Many full-time workers who receive minimum-wage salaries live at or near the federal poverty level. This means that many must turn to public assistance such as food assistance and Medicaid in order to make ends meet. By allowing businesses to pay poverty-level wages, lawmakers have relieved low-wage employers of their legal responsibility to adequately compensate their workers—leaving American taxpayers to foot the bill instead. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, recently estimated that low wages cost U.S. taxpayers a whopping $152.8 billion each year. Yet for workers who cannot make ends meet on paltry pay, public assistance programs are critical to survival.

In a recent study, the Center for American Progress analyzed the impact of past minimum-wage changes on spending in one particular program—the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, formerly known as food stamps. The study found that minimum-wage increases lead to statistically significant reductions in SNAP enrollment and spending. When workers’ incomes are increased, some end up relying less on SNAP benefits while others see their earnings boosted above the threshold for SNAP eligibility, which stands at 130 percent of the federal poverty level.

Because SNAP benefits decrease by only $0.30 for each additional dollar earned, workers are left far better off with a wage increase than they were with lower pay and higher SNAP benefits. Taxpayers, meanwhile, spend less money on SNAP. The result is a win-win situation for both low-wage workers and taxpayers.

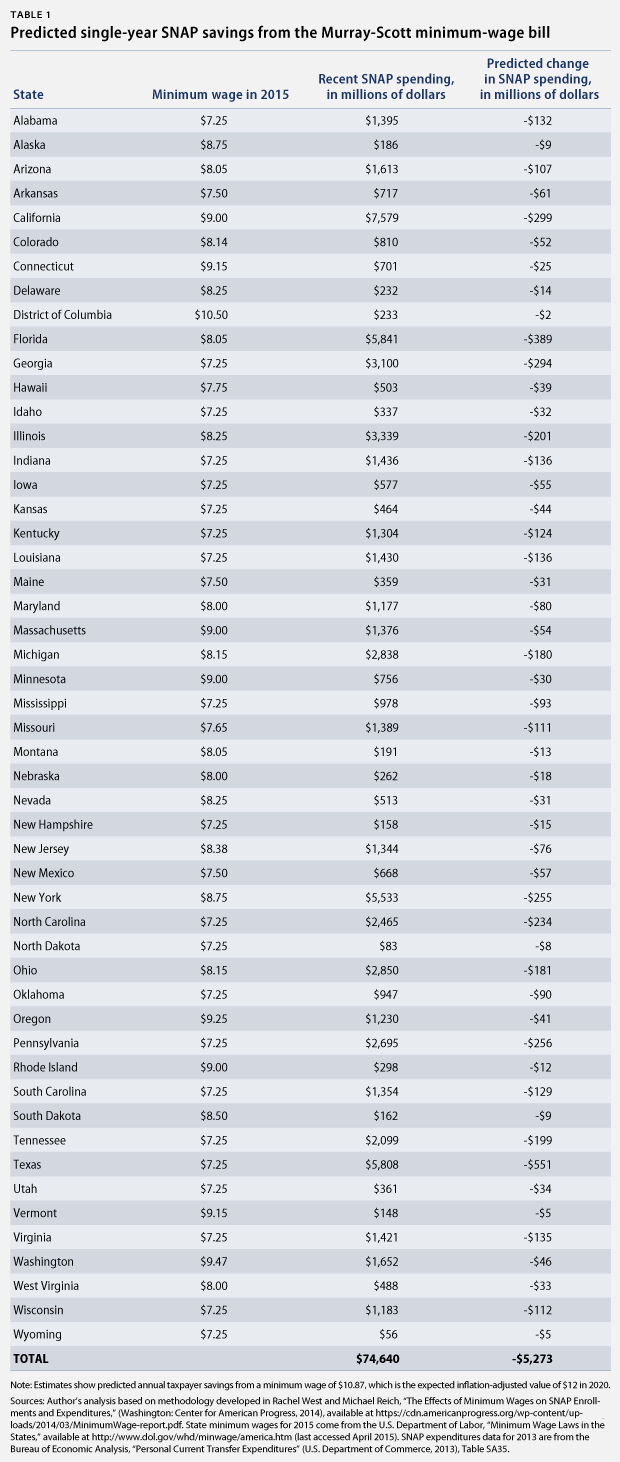

In the table below, this study’s results are applied to the Murray-Scott bill, accounting for states’ 2015 minimum wages and using the most recently available SNAP data. If average inflation meets the Federal Reserve’s target rate of 2 percent per year between now and 2020, the Murray-Scott bill’s $12 per hour minimum wage would be equivalent to about $10.87 in today’s dollars. When fully implemented, the increase in workers’ income from a minimum wage of this value would cause SNAP spending to fall by an estimated $5.3 billion each year in today’s dollars, saving taxpayers more than 7 percent in overall SNAP expenditures.

Because the bill would index the minimum wage to the median wage after 2020, the minimum wage could be expected to increase at a similar rate to SNAP benefit levels thereafter, since the SNAP eligibility threshold is indexed to inflation.* Consequently, taxpayer savings over the subsequent decade would be 10 times the one-year savings of $5.3 billion, standing at $52.7 billion in today’s dollars.

No one who works full time should live in poverty. In addition to ensuring basic dignity and protecting the economic security of working families, a higher minimum wage would deliver multiple other benefits, including saving American taxpayers billions of dollars. Instead of slashing SNAP benefits—as some have recently proposed—lawmakers could use a minimum-wage increase to reduce SNAP spending in a way that benefits taxpayers, boosts the economy, saves jobs, and leaves working families better off. The Raise the Wage Act represents a new generation of minimum-wage policy that could make these benefits a reality.

Rachel West is a Senior Policy Analyst in the Center for American Progress’s Poverty to Prosperity Program.

* Correction, April 30, 2015: This column incorrectly stated the Raise the Wage Act’s index metric for the minimum wage. The Raise the Wage Act would index the minimum wage to the median hourly wage starting in 2020. The column has also been updated to reflect that a minimum wage indexed to the median wage would have a different relationship with SNAP benefits.