When designing programs and policies for the LGBTQ community, lawmakers should consider the needs of bisexual people of color. About half of the LGBTQ community is bi+, meaning they identify as bisexual, queer, pansexual, or some other identifier indicating attraction to more than one gender.1 Like the general population, the majority of LGBTQ people in the United States are white, but people of color are more likely than their white peers to identify as LGBTQ.2 Disaggregating data by sexual orientation and race can provide more insight into the variety of experiences among the LGBTQ community.

This analysis builds on a previous Center for American Progress study on bisexual and queer people.3 Using nationally representative survey data, it compares bi+ respondents with their monosexual—gay, lesbian, or straight—peers. Unlike the 2018 study, however, this analysis also presents differences along racial lines, with separate data for white respondents and respondents of color on self-reported physical and mental health outcomes and caregiving roles. Previous research has found disparities in health outcomes and parenting rates for bisexual people but did not disaggregate findings by race.4 Including both sexual orientation and race in these areas of study can contribute to current policy debates on health care access, paid family leave, and workplace protections.

While this analysis disaggregates survey findings by race, comparing white respondents with respondents of color, further disaggregation by race and ethnicity was not possible due to small sample sizes. Some differences were not statistically significant, though this may be due to the small sample sizes or differences among specific races or ethnicities being obscured. (see Methodology) This analysis suggests that some findings of differences between bisexual and monosexual people in previous studies may not hold true for people of color and that further research is needed to identify and understand these patterns.

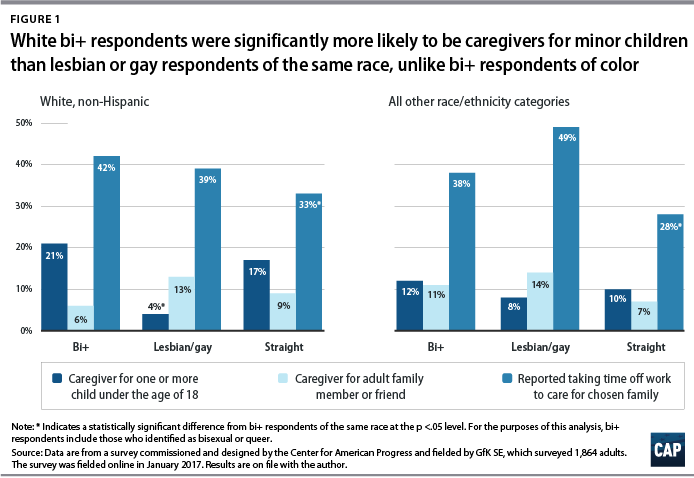

As shown in Figure 1, there were no statistically significant differences in caregiving for adult family or friends by sexual orientation for either white respondents or respondents of color.

White bi+ respondents were more likely to be caregivers for minor children, in line with previous findings that bisexual people are more likely to be parents.5 However, disaggregating the data by race revealed that among people of color, there were no statistically significant differences by sexual orientation. Further research can help clarify whether people of color of all sexual orientations behave similarly in terms of providing care for children, as well as which factors contribute to this similarity. What’s more, white bi+ respondents and bi+ respondents of color were both more likely than their straight counterparts to have taken time off from work to care for chosen family. Prior research has shown that while caring for chosen family is a remarkably common occurrence in the United States, LGBTQ people are more likely than non-LGBTQ people to take on this role.6

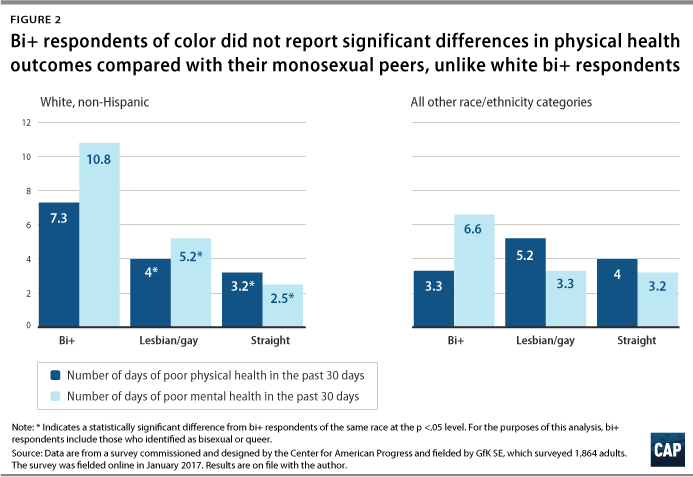

White bi+ respondents reported poorer physical and mental health outcomes than their white monosexual counterparts, in accordance with previous studies on this topic.7 But any differences in health outcomes among people of color were not statistically significant, though this may be due to small sample sizes. Survey results suggest that differences in mental health outcomes by sexual orientation may be greater for white people than for people of color, and there were no notable differences by sexual orientation for physical health outcomes among people of color. Future studies on the health outcomes of people of color should collect data on sexual orientation to clarify whether there are any meaningful differences requiring further study and intervention.

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrates the importance of disaggregating data by race and ethnicity when studying the experiences of bi+ people. Prior research has shown meaningful differences between bisexual and queer people and their monosexual peers, but this study suggests that these differences across sexual orientation may not be as significant for people of color. Targeted research with larger sample sizes can help health care providers, researchers, and policymakers better understand this population and how the interactions between sexual orientation and race affect people’s health and family lives.

Shabab Ahmed Mirza is a research assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Rasheed Malik and Laura Durso for their assistance with this fact sheet.

Methodology

To conduct this study, the Center for American Progress commissioned and designed a survey, fielded by GfK SE, which surveyed 1,864 adults, including 857 adults who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender, queer, or asexual and 1,007 who identified as heterosexual and cisgender/nontransgender. The data are nationally representative and weighted according to U.S. population characteristics. After weighting, the sample size of all LGBTQ respondents was 135. Respondents came from all income ranges and were diverse across factors such as race, ethnicity, education, geography, disability status, and age. The survey was fielded online in English in January 2017. All comparisons presented with an asterisk in the figures and tables are statistically significant at the p < .05 level. Comparisons that were not found to be statistically significant do not have an asterisk.

Due to small sample sizes, respondents of color were grouped into the category of “all other race/ethnicity categories,” which includes those who identified as Black non-Hispanic, other non-Hispanic, multiracial non-Hispanic, and Hispanic.

Additional information about study methods and materials are available from the author.