The Center for American Progress and the Equal Rights Center, or ERC, recently conducted telephone tests on 100 homeless shelters across four states. The tests measured the degree to which transgender homeless women can access shelter in accordance with their gender identity, as well as the types of discrimination and mistreatment they face in the process. While accessing homeless shelters is difficult for anyone, transgender women face particular issues and barriers that have yet to be addressed.

Current law: the Equal Access Rule

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LGBT, people are not explicitly protected from discrimination under the federal Fair Housing Act. However, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, sought to remedy this through the Equal Access Rule, or EAR, which makes it illegal to discriminate against LGBT individuals and families in any housing that receives funding from HUD or is insured by the Federal Housing Administration, regardless of local laws. As currently written, EAR prohibits inquiries into an individual’s sexual orientation and gender identity and does not address the right of transgender shelter-seekers to access shelter in accordance with their gender identity.

Study results

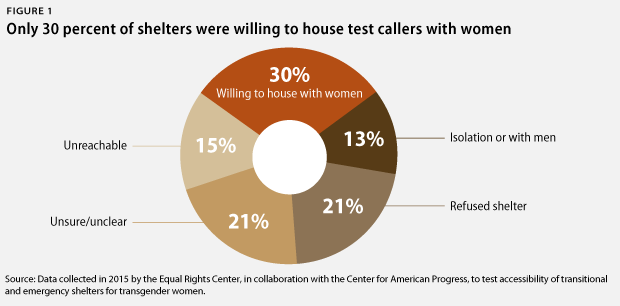

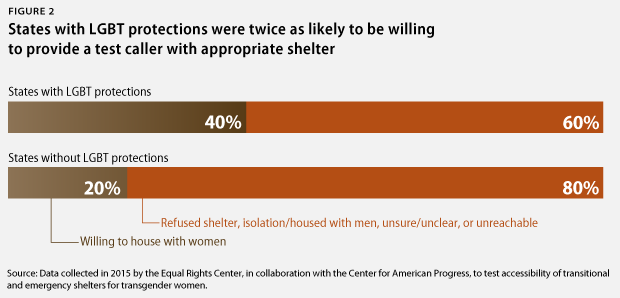

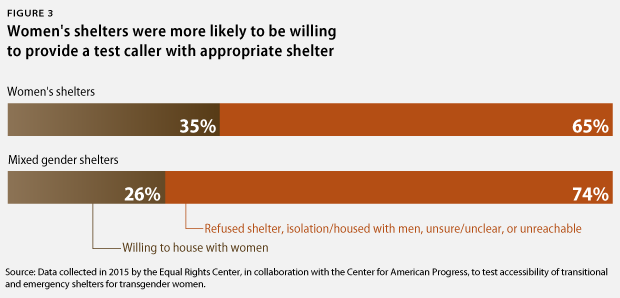

Overall, only a minority of shelters was willing to properly accommodate transgender women. This willingness varied depending on state laws and shelter type.

7 ways transgender women were mistreated by shelter employees:

- There was a discrepancy between the positive information given to the advance caller and the negative information given to the test caller. One shelter, for example, hung up on the tester immediately after she revealed she was transgender.

- A shelter employee deflected the decision or service to another employee or agency.

- The test caller was told that she would be isolated or given separate facilities at the shelter.

- A shelter employee misgendered the tester or made other statements to discredit her identity.

- A shelter employee made references to genitalia or to surgery as requirements for appropriate housing.

- A shelter employee made insinuations that other residents would be made uncomfortable or unsafe by the tester.

- A shelter employee explicitly refused to shelter the tester or placed the tester in a men’s facility or in isolation. This happened 34 percent of the time.

Examples of interactions between caller and shelter employee

The following are excerpts from notes taken by the test callers and provided to the research team. They have been lightly edited for style and clarity.

Examples from Virginia shelters:

The shelter employee explained that other women would not find it fair or comfortable that they have to share their bathroom with a “man” and said that ultimately the test caller’s placement would be determined by genitalia and legal status. The shelter employee said that test caller had to be “complete” otherwise it would not be fair to the other women. The shelter employee also told the test caller that there were other shelters in Alexandria, Virginia and Falls Church, Virginia that the test caller could try. The employee seemed to get frustrated at the end of the call and gave the test caller the phone number for the intake line and told the test caller to just explain their situation to them. The shelter employee referred to test caller as “sir” throughout the call.

The test caller was told that she would have to be housed with men if she had not had surgery. The shelter employee said the reason was fear of rape on the women’s floor. The test caller asked about her own safety on the men’s floor and was told that she would be put in a separate room with a door that locked.

Example from a Washington shelter:

The test caller was informed that she could only stay at the shelter if she had had surgery. The shelter employee’s supervisor reiterated that policy and said that because the test caller still had “man parts” she was still a man and would make the other women uncomfortable.

What should be done?

- Congress should pass the Equality Act to ensure that all LGBT people are protected from discrimination in areas such as housing, public accommodations, employment, and credit. States without these protections should pass comprehensive nondiscrimination legislation.

- The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development should issue guidance to modify the equal access rule in order to clarify that individuals have the right to be housed according to their gender identity and that the only exception to this would be if the transgender person requests alternative accommodations for their own safety.

- HUD should also modify the equal access rule to allow shelters to ask about an individual’s sexual orientation and gender identity in order to properly accommodate them, but still prohibit them from using this information to discriminate.

Methodology

The phone survey consisted of calls to 25 homeless shelters in each of four states, for a total of 100 shelters. These calls were made over the course of three months, from March 1, 2015 to June 1, 2015. Each test consisted of a control call in advance—conducted by a cisgender, female Equal Rights Center staff member or intern—followed by the test call from one of four self-identified transgender women recruited and trained by ERC. The advance caller provided control information like bed availability and extent of follow-up. The test caller introduced herself as a transgender woman who was homeless and in need of shelter. She then asked about the availability of a bed and the shelter’s willingness to house her with other women.

The shelters were spread across four states: Connecticut, Washington, Tennessee, and Virginia. Forty shelters exclusively served women, while 60 were mixed-gender shelters. Twenty-seven percent of the shelters had ever received funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in the past.

The four states were selected based on a range of characteristics. Two states—Connecticut and Washington—have gender identity nondiscrimination protections, while the other two—Tennessee and Virginia—lack them. There are variations in the size of the LGBT population across the states: 3.4 percent in Connecticut, 4 percent in Washington, 2.6 percent in Tennessee, and 2.9 percent in Virginia. The four states are also geographically diverse and have comparable seasonal weather, which controls for variation in service due to these conditions.

Connecticut and Washington use a centralized system—the 211 line—for accessing homeless shelters; Tennessee and Virginia do not. The methodology was adjusted accordingly. For shelters in Connecticut, the tester told the shelter employees that she had previously called 211 and had been told to contact the shelter directly to see if she could be accommodated there before going through the 211 intake process. For the shelters in Washington, the test caller was instructed to attempt the test with the standard assigned methodology. If the test caller was told to call the central referral line, she stated that 211 suggested that she contact the shelter directly to see if she could be accommodated before going through the intake process.

Caitlin Rooney is the Special Assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center. Laura E. Durso is Director of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center. Sharita Gruberg is a Senior Policy Analyst for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center.