Communities that have long experienced structural inequality in the United States are now also being hit harder by the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. People of color, women, LGBTQ people, and groups living at the intersections of those identities encounter systemic factors that lead them to work in industries with low job security and employment without paid leave, making recovery during a pandemic significantly more challenging.

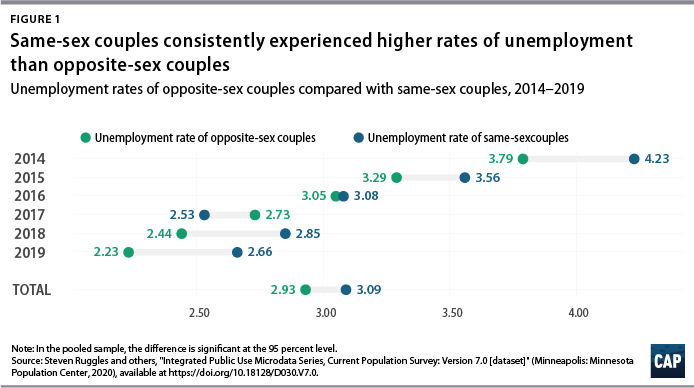

Early research from the Williams Institute at University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and the Human Rights Campaign demonstrates that LGBTQ people are facing higher rates of unemployment than non-LGBTQ populations due to the current crisis. This, unfortunately, shows similar trends to a new CAP analysis of several years of employment data, reflecting the recovery from the last recession. The CAP analysis indicates that households headed by same-sex couples are disproportionately affected by unemployment during a crisis compared with those headed by different-sex couples and that higher unemployment rates persist for this group after an economic crisis.

Starting in late 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau began officially counting same-sex couples as part of the Current Population Survey (CPS), the largest monthly survey of American households. This long-overdue process began in May 2015, when the Census Bureau revised its questions on relationship to heads of households to specify whether the household member is the same-sex spouse or same-sex unmarried partner of the head of household. With those data, the bureau was able to estimate that there are 543,000 same-sex married couple households and 469,000 same-sex unmarried couple households in the United States, and 191,000 children live with same-sex parents.

Other changes to the underlying public use data made available to researchers have made it possible to identify same-sex couples, including the marital status of cohabitating partners in older data—information that, until recently, was edited out of the reports by the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics.

CAP’s analysis of these employment data show that same-sex couples experienced unemployment at higher rates than Americans as a whole nearly every year between 2014 and 2019.

The survey data also demonstrate that households headed by same-sex couples are significantly more likely than opposite-sex-headed households to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. This corroborates earlier CAP research that showed LGBTQ people and their families are more likely to participate in federal benefit programs than non-LGBTQ families as well as research from organizations such as the Williams Institute at UCLA on the disproportionate levels of poverty among LGBTQ people. Research demonstrates that LGBTQ people experience widespread discrimination in the workplace, which could be a contributing factor to the persistent high unemployment rates for same-sex couples.

Although a growing number of federal courts across the country have affirmed that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act’s prohibition on sex discrimination in the workplace prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, the U.S. Supreme Court is currently considering this issue. If the court removes federal workplace protections for LGBTQ workers, it will set civil rights protections for LGBTQ people backward by years and eliminate a key tool for addressing employment disparities. This would leave half of LGBTQ workers without recourse if they face employment discrimination such as being fired from a job or not hired in the first place simply because they are LGBTQ.

Discrimination likely contributes to higher unemployment rates and low job mobility for same-sex couples

Longtime legal inequality and widespread employment discrimination are factors that likely contribute to the higher unemployment rates of same-sex couples. Federal workplace protections do not explicitly prohibit discrimination against LGBTQ people; however, the Equal Employment and Opportunity Commission—the federal agency tasked with enforcing Title VII of the Civil Rights Act—ruled in 2012 that the law prohibited gender identity discrimination and in 2015 that it prohibited sexual orientation discrimination. Subsequently, the commission has resolved 10,097 LGBT-based workplace sex discrimination complaints since fiscal year 2013. In 2014, then-President Barack Obama enacted Executive Order (EO) 13672, which amended EO 11246 to extend prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity to federal contractors, expanding protections to cover approximately one-fifth of all U.S. civilian employees. Unfortunately, the U.S. Department of Labor is proposing to undermine these protections.

While these advances are critical both in providing recourse for people who face mistreatment and in sending the message that LGBTQ people are full and equal citizens, LGBTQ workers continue to face high levels of discrimination in the workplace. A nationally representative survey from CAP found 1 in 4 LGBTQ adults experienced discrimination in the year prior. And 52.8 percent of LGBTQ adults reported that discrimination negatively affected their work environment. Furthermore, 1 in 5 LGBTQ people reported being discriminated against when applying for jobs because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, according to a survey from NPR and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

CAP’s analysis also found that same-sex couples were more likely to be working for the same employer as in the previous year. This may sound like good news for job stability, but economists typically view job switching as positive. People who switch jobs experience faster earnings growth, and a relative lack of job switching—as seen among same-sex couples—is consistent with workers staying with a single employer because outside options are likely to expose them to discrimination.

This is in line with avoidance behaviors reported in CAP’s survey such as hiding their sexual orientation or gender identity from prospective employers by removing items from their resume (9.5 percent) or making specific decisions about where to work to avoid discrimination (13.2 percent). These avoidance behaviors were more common in LGBTQ people who had experienced discrimination in the past year, with 22.6 percent reporting removing items from their resume and 27.7 percent deciding where to work to avoid discrimination.

More data are needed to fully understand the economic security of LGBTQ adults

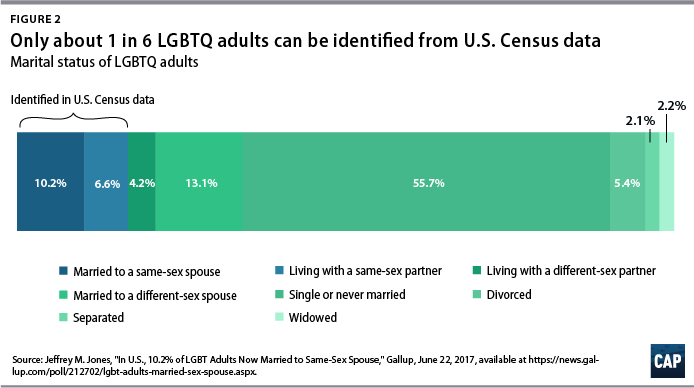

While these data provide us with information on households headed by same-sex couples, the CPS does not collect sexual orientation and gender identity information, so there is only insight into the experiences of a small percent of the country’s LGBTQ population. According to Gallup data, because only 10.2 percent of LGBTQ people are married to a same-sex spouse and 6.6 percent live with a same-sex partner, the current CPS data can only account for 16.8 percent of the adult LGBTQ population. Nearly half of all LGBTQ adults identify as bisexual or queer, and LGBTQ adults are more likely to be married to a different-sex spouse. This is especially important in CPS data because they are such a rich source of information for researching trends in employment and earnings over time, including in response to policy changes. They are also the underlying data that allow for key comparisons across groups; access to these data is why we know women overall earn 82 cents for every dollar a man earns, why the disparity is even greater for women of color, and why the Black unemployment rate is double the white unemployment rate with strikingly consistency.

Very few federal surveys collect sexual orientation and gender identity data, which contributes to our limited understanding of economic and employment experiences of LGBTQ adults. We need more data on the experiences of LGBTQ people to better understand their experiences and to ensure policies are enacted and implemented in ways that meet their needs.

Conclusion

CAP’s analysis of CPS data demonstrates that even in an economic recovery, same-sex couples are left behind. While we do not yet have data on the impact the current economic crisis caused by COVID-19 is having on same-sex couples, if history is any indication, they will be disproportionately harmed by this crisis and will experience a longer recovery. If the Supreme Court holds that it is legal to fire someone simply because they are LGBTQ, workers living in the 28 states that lack explicit and comprehensive workplace protections would be left without recourse and put at even more risk of losing a job or not being hired in the first place just because of who they are or who they love, leading to even greater economic insecurity.

The Equality Act, a bipartisan bill to update the Civil Rights Act to ensure LGBTQ people have explicit protections in key areas of life, passed in the U.S. House of Representatives last year, and Virginia recently became the first state in the South to enact comprehensive nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ people. A large majority of Americans across party lines and across the country support these protections. Rather than making it more difficult for LGBTQ workers to obtain and retain employment, the federal government should ensure they are protected from discrimination and treated as equally as all other workers.

Sharita Gruberg is the director of policy for the LGBTQ Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center.