Introduction and summary

February 2019 will mark the 50th anniversary1 of Bill Jones finalizing the adoption of his son, Aaron. In 1969, Jones became the first single man in California—and likely the United States—to adopt a child. He is also gay. The social worker who helped him adopt told him that outing himself as gay would destroy his chances of adopting, because the agency would have been “obliged” to deny him.2 The intense scrutiny and lengthy process he faced just as a single man trying to adopt only confirmed this warning.

Sadly, half a century later, LGBTQ prospective parents interacting with the child welfare system still face discrimination because of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. In a 2011 national survey of 158 gay and lesbian adoptive parents, nearly half of respondents reported experiencing bias or discrimination from a child welfare worker or birth family member during the adoption process.3

Despite this bias, the vast majority of U.S. states still lack laws or policies that explicitly protect LGBTQ prospective adoptive and foster parents from discrimination.4 It was not until 2003, 34 years after Jones adopted his son, that California passed its first law against discrimination toward qualified prospective foster and adoptive parents.5 The last statutory ban on allowing same-sex couples to adopt was not struck down until 2016,6 and the last statewide policy banning same-sex couples from being foster parents was not struck down until 2017.7 The absence of affirmative protections in the child welfare system for LGBTQ people and same-sex couples threatens the ability to place children in this system in safe homes.

Worse still, certain conservative religious groups are weaponizing their anti-LGBTQ viewpoint to advocate for religious exemptions that allow child placing agencies to discriminate. These laws allow state-funded child placing agencies to refuse to serve qualified prospective parents based on the religious beliefs of the agencies’ leaders. This would enable agencies to turn away loving prospective parents based on the parents’ sexual orientation or gender identity. As of October 2018, 10 states have passed laws allowing child placing agencies to turn away prospective parents for religious reasons.8 These laws deprive foster youth of potential families at a time when the child welfare system cannot afford to be turning away qualified parents.9

As of 2017, there were approximately 443,000 children in foster care nationwide.10 Each year, more than 50,000 children are adopted through the U.S. child welfare system, but about 20,000 age out of the system without ever finding a permanent family.11 Turning qualified prospective parents away only stresses an already stressed system, and LGBTQ people represent an important subgroup of potential parents. In Massachusetts, for example, between 15 percent and 28 percent of adoptions from foster care have involved same-sex parents every year for the last decade.12 Same-sex couples raising children are seven times more likely to be raising a foster child and seven times more likely to be raising an adopted child than their different-sex counterparts.13 They are also more likely to adopt older children and children with special needs, who are statistically less likely to be adopted—perhaps because many LGBTQ parents can empathize with the stigmatization such children may experience.14 Numerous studies have also shown that children of gay or lesbian parents fare as well as children of different-sex parents; they are also just as healthy, both emotionally and physically.15 The longest-running study on the children of lesbian parents specifically recently came to the same conclusions.16

Finding permanent families for children in the foster care system has positive benefits for those young people: Studies comparing children who remain in foster care with children who are adopted have shown that adopted children are 50 percent less likely to be arrested, 20 percent less likely to become teen parents, and 24 percent less likely to experience unemployment as adults.17 Given these data, it does not make sense for child welfare agencies to turn away LGBTQ prospective adoptive parents.

Fortunately, public opinion is on the side of equality and justice. Since 2008, a majority of Americans have consistently supported the legal right of same-sex couples to adopt.18 Today, more than two-thirds of Americans oppose allowing child placing agencies that receive federal funding to refuse to place children with a same-sex couple, and more than half of Americans oppose such refusals regardless of whether the agency receives government funding.19

This report reviews the child placing agency landscape in the United States, as well as some of the negative effects that religious exemptions are likely to have. First, it explores the current legal landscape of protections for LGBTQ foster and adoptive parents, including state and federal attempts to secure harmful religious exemptions through legislation and litigation. Next, the report considers the impacts of religious exemptions on overburdened child welfare systems, using data on federal funding for foster care and adoption to examine the economic costs of being unable to find permanent homes for children. The authors also use case studies of two states—Michigan and Texas—to assess the potential negative impact of these laws on LGBTQ people’s ability to become foster or adoptive parents. The report concludes with recommendations on how to best eliminate discrimination against LGBTQ prospective foster and adoptive parents.

Case study analyses revealed that secular agencies in Texas and Michigan were more likely to have posted sexual orientation- and/or gender identity-inclusive nondiscrimination policies on their websites, something that faith-based agencies were less likely to do. The analyses also highlighted how few agencies have posted nondiscrimination policies on their websites generally, much less ones inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity. In addition, the locations and geographic concentrations of welcoming versus unwelcoming agencies indicates that accessing explicitly LGBTQ-inclusive child welfare services is likely to be challenging for families in these two states. For example, in three of the 10 most populous Texas cities, there is no agency that is explicitly affirming of LGBTQ people within the greater metropolitan region. Finally, available data analyzed for this report suggest that federal taxpayers could save hundreds of millions of dollars during the eight years it would otherwise take for a 10-year-old in care to age out of the system if child welfare agencies were able to increase their adoption rates by expanding their pool of prospective parents.

This report illuminates a confusing and difficult landscape for LGBTQ people who wish to foster or adopt. In states with religious exemption laws, taxpayers are shouldering costs that could be lessened were child welfare agencies to ensure that their pool of prospective parents included all qualified families, regardless of parents’ sexual orientation or gender identity. State governments must enact nondiscrimination laws for prospective foster and adoptive parents that are inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity, and states with religious exemptions for child placing agencies must repeal them.

The legal landscape of the U.S. child welfare system for LGBTQ people

In a legal sense, many LGBTQ people interacting with child placing agencies are treated like second-class citizens. In too many states, LGBTQ prospective parents and LGBTQ youth in foster care lack nondiscrimination protections. Several states without nondiscrimination protections have even pre-emptively enacted religious exemptions in anticipation of having to comply with nonexistent nondiscrimination protections. These exemptions are even more damaging, as they give official governmental approval to discrimination. Meanwhile, the courts are debating if LGBTQ people can be refused service.20 And the fact that the legal landscape of child welfare is unwelcoming to the LGBTQ community likely leads to decreased engagement in fostering and adoption than would otherwise occur.

Nondiscrimination protections are lacking in the child welfare system

Too few states have statutory or even regulatory nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ prospective parents and/or youth interacting with the child welfare system.

Nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ foster youth

Studies have found that between 19 percent and 23 percent of youth in the U.S. foster care system identify as LGBTQ, meaning that LGBTQ youth are overrepresented in the foster care system by at least a factor of two.21 Abuse, rejection by their families, and discrimination all contribute to this overrepresentation.22

LGBTQ youth in foster care generally have more nondiscrimination protections than LGBTQ prospective parents. However, 13 states still lack explicit nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ foster youth.23 There are 37 states that provide protections for youth in the child welfare system through laws, regulations, or agency policies: 24 states and Washington, D.C., provide protections on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity, and 13 states provide protections on the basis of sexual orientation only.24 Three states with nondiscrimination protections have issued explicit guidance to agencies to house transgender youth according to their gender identity.25 Nine states with nondiscrimination protections require child welfare agency staff and/or foster parents to undergo LGBTQ-inclusive cultural competency training.26

While these protections are crucial to ensuring that LGBTQ youth are treated fairly in the U.S. child welfare system, not all states offer them. LGBTQ foster youth continue to report mistreatment and discrimination at twice the rate of their non-LGBTQ peers.27

Thomas’ story

When Thomas H. of Oklahoma was 12, he came out as gay to his foster family.28 From that moment on, everything changed. His once loving foster family shamed him and told him that he was condemned to hell. They made him feel like he was unlovable because of his sexual orientation. His foster family would even encourage the other children, who were twice Thomas’ size, to attack him in an attempt to teach Thomas how to be more stereotypically masculine and fight back. Thomas’ foster mother at the time was a therapist at the foster agency, making it difficult for him to speak out. Despite many cries for help, The agency ignored Thomas and made him out to be a liar and a troublemaker.

The emotional and physical toll was so severe that Thomas attempted suicide. After leaving that foster home, he was placed in group homes, behavioral health centers, and detention centers. For the next five years of his life, Thomas was attacked, both physically and verbally, and discriminated against because of his sexuality. Being raised in hostile situations made Thomas’ transition to adulthood difficult. He faced many challenges with creating and maintaining healthy relationships and support systems, as well as managing his mental health. Thomas is a survivor, though, and connected with his final foster family before aging out of the system. With that positive support, Thomas was able to graduate from college. He now works as an advocate for LGBTQ youth in foster care.

Nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ prospective parents

Although same-sex parents are no longer banned from fostering or adopting, they are still largely unprotected from discrimination as they seek to become foster or adoptive parents. The vast majority of states—42—lack laws or policies that explicitly protect LGBTQ people from discrimination in the foster system.29 Among the eight states that have affirmative nondiscrimination protections for foster parents, five states protect prospective parents from discrimination based on sexual orientation, while three states and Washington, D.C., protect against discrimination on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity.30 Forty-three states, meanwhile, lack explicit laws protecting LGBTQ prospective parents from discrimination in adoption. Seven states protect parents from such discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, while only three states and Washington, D.C., protect parents on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity.

Admittedly, there is some complexity31 in how states are or are not counted as having protections. Some states not counted in the categories above, such as Connecticut, still protect prospective parents through a broad LGBTQ nondiscrimination law, even if it lacks a specific law that protects against discrimination in child welfare.32 The several states that have protections on the basis of sex could also offer some protection to LGBTQ prospective parents, and youth in care, as courts increasingly interpret sex to include gender identity and sexual orientation.33 Yet, while these laws are undoubtedly a marker of progress, explicit nondiscrimination protections enumerating sexual orientation and gender identity as protected classes are still necessary in order to protect everyone and to instruct those enforcing the law on exactly how and when to do so.34

John’s story

John Freml of Illinois was drawn by his Catholic faith to foster a child, as he recognized that so many children are in need of stable, loving families.35 In December 2015, he and his husband Ricky became licensed foster parents in Springfield through a private fostering and adoption agency. The next month, they welcomed a newborn girl into their home. Based on conversations with their caseworker, they were under the impression that they were on the path to adopting their foster daughter. Later, however, the child’s extended biological family found out she was being fostered by a same-sex couple and subsequently fought for her to be placed with them instead.* Despite two independent reviews that found allowing the child to remain with John and Ricky was in her best interest, the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services ultimately removed her from John and Ricky’s home. The couple believes that their sexual orientation was the key factor in the girl’s removal.

* Please note that the authors strongly support family reunification and kinship placement when it is in the child’s best interest.

Religious exemptions for child placing agencies provide license to discriminate

In the courts, in state legislatures, and at the federal level, anti-equality activists are pushing for laws and policies that would allow child welfare providers to opt out of working with LGBTQ prospective parents—and even out of providing affirming care to LGBTQ youth—under the guise of religious liberty. As noted above, more than 40 states currently lack explicit nondiscrimination protections that cover sexual orientation and gender identity for prospective foster or adoptive parents; 10 of these states provide religiously affiliated child welfare agencies with a license to discriminate against LGBTQ prospective parents and, sometimes, children in their care. These states are: Alabama, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, and Virginia.36 While the first of these laws was passed in North Dakota in 2003, they have been gaining momentum in recent years: Two were passed from 2015 through 2016, three in 2017, and three in 2018.37

These laws vary in whether they cover discrimination on the basis of both moral beliefs and religious beliefs, as well as in how they define the burden for proving a sincerely held religious belief. They also vary in whether they explicitly allow agencies to refuse to refer LGBTQ prospective parents to another agency and in whether they allow discrimination against LGBTQ prospective parents or against both parents and LGBTQ youth in care. Laws that allow child welfare agencies to discriminate against children based on the agency’s religious views may enable a foster parent to force an LGBTQ youth to undergo conversion therapy, a widely discredited and harmful practice that seeks to change an individual’s sexual orientation or gender identity.38

In South Carolina, the license to discriminate is also enshrined in an executive order. In March 2018, four months before the state passed a religious exemption law for child placing agencies, the governor signed an executive order that prohibits the state’s Department of Social Services from denying licenses to religiously affiliated child placing agencies that engage in discrimination on the basis of their religious beliefs. The state is also requesting that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provide it an exemption from the federal HHS regulation governing the granting of federal funds, which forbids discrimination on the basis of, among other things, religion, sexual orientation, and gender identity.39 With this request, South Carolina is not only seeking to allow discrimination against LGBTQ parents, but also to allow agencies, such as Miracle Hill, to discriminate against people who have different religious beliefs.40 If the HHS grants this exemption, it would set a dangerous precedent—and would underscore that the true purpose of so-called religious exemptions is to protect certain religious beliefs, not the rights of people of all religions.

Miracle Hill, the largest provider of foster families in South Carolina, made headlines this year for turning away a Jewish couple. Beth Lesser and her husband have a decade of experience as foster parents, and yet Miracle Hill refused to work with them because they are not Christian. It instead referred them to a different agency. In an interview on her experience, Beth said, “To say we can go somewhere else is like saying you can’t use this state-funded hospital, but you can go to the one down the street.”41 Other states’ religious exemption laws could also be read as allowing religious discrimination,42 even though doing so runs afoul of federal law and likely the U.S. Constitution.43

At the federal level, some members of Congress have introduced similarly broad licenses to discriminate against parents and children. The Child Welfare Provider Inclusion Act, introduced by U.S. Sen. Mike Enzi (R-WY) and U.S. Rep. Mike Kelly (R-PA) in April 2017 and still pending in the House Committee on Ways and Means Subcommittee on Human Resources, would prevent the federal government, as well as state and local governments that receive federal funding, from taking any adverse action against child welfare agencies that discriminate on the basis of their religious beliefs or moral convictions.44 In July 2018, U.S. Rep. Robert Aderholt (R-AL) introduced the Aderholt amendment to the fiscal year 2019 appropriations bill for the departments of Labor, HHS, Education, and Defense.45 The amendment, which was ultimately dropped from the final version of the law, would have cut federal child welfare funding by 15 percent for states that require their child placing agencies to not discriminate against prospective foster and adoptive parents or youth in foster care. Under this amendment, child placing agencies would have been explicitly allowed to decline to provide services based on their moral or religious beliefs.46 This undoubtedly would have led to agencies turning away LGBTQ prospective parents—meaning fewer families for youth in care.47

Given the significant number of children waiting for permanent homes, more, not fewer, prospective parents are needed. Religious exemptions for child placing agencies likely only exacerbate this gap by preventing qualified LGBTQ people from becoming parents, while providing government approval and taxpayer funding for discrimination.

The courts are reviewing religious exemptions for child placing agencies

Federal courts are currently considering whether government-contracted child placing agencies can discriminate against LGBTQ prospective parents. There are two main types of these cases: those that deal with nondiscrimination laws and those that deal with religious exemptions. The former type includes cases such as Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, in which an anti-LGBTQ child placing agency is suing to receive a city contract even though the agency refuses to approve same-sex couples as foster parents—a violation of Philadelphia’s nondiscrimination policy.48 The latter type includes cases such as Dumont v. Lyon in Michigan, in which LGBTQ prospective parents argue that the state’s religious refusal law is unconstitutional.49 This type also includes cases such as Marouf v. Azar, in which LGBTQ prospective parents argue that it is unconstitutional for the federal government to continue funding agencies it knows are engaging in discrimination.50

LGBTQ nondiscrimination laws

Some child welfare agencies seeking a religious exemption for child placing allege that nondiscrimination laws protecting LGBTQ prospective parents are unconstitutional. These agencies claim that these protections target specific religious beliefs—those that oppose same-sex parents raising children—despite the fact that nondiscrimination requirements apply to all contractors and concern the contractors’ conduct, not their personal beliefs. Providers do not have a right to receive a government contract, and if they voluntarily enter into one, they must abide by its terms. Indeed, also contradicting the claim that nondiscrimination protections target certain religious beliefs is the willingness of the government to contract with religious providers who follow the law, as well as to re-enter a contract with a provider once that provider stops discriminating.

These agencies also argue that nondiscrimination protections constitute compelled speech and retaliation against free speech. However, providers do not have to make a public statement about their beliefs on same-sex marriage. Finally, these agencies claim that nondiscrimination protections do not further a compelling government interest, even though courts have found a compelling interest several times for enforcing nondiscrimination laws.51

Religious exemptions for child placing agencies

Challenged by prospective LGBTQ parents in the courts, conservatives, including some governments and discriminatory agencies, argue that religious exemptions pass constitutional muster. These groups allege that these laws do not violate the establishment clause, because they do not promote a particular religion—even though such religious exemptions appear to assert certain Evangelical Christian and Catholic beliefs.52 These groups also argue that religious exemption laws do not violate the Establishment Clause or the Equal Protection Clause, because the government itself is not engaging in any discrimination; it is contracting with the agencies to provide government services on its behalf.

Meanwhile, LGBTQ prospective parents counter that child welfare agencies’ refusal to serve same-sex couples violates their rights under the Equal Protection Clause, a claim at least one court has found plausible.53 And even in cases where there is no official religious exemption for child placing agencies, such as Marouf v. Azar, plaintiff prospective parents argue that the government is responsible for knowingly contracting a public function to and funding a private agency while aware that the private agency is conducting its function in a discriminatory way.

Another claim discriminatory agencies make is that religious exemption laws allow the state to contract with a wider group of agencies, including faith-based agencies, which furthers the compelling government interest in serving more children. This is a questionable claim, however, since the agencies’ ability to turn away qualified families undermines the state’s interest in providing as many permanent, loving homes as possible for children in the system.

The status of litigation

As of October 2018, preliminary rulings in two of the three main cases pending on the issues of nondiscrimination and religious exemptions for child placing agencies have taken steps to protect LGBTQ people. In Dumont v. Lyon, the federal district court has held that Michigan may be in violation of the U.S. Constitution by “expressly acknowledging and accepting” that certain child placing contractors “may elect to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation in carrying out those state-contracted services.”54 In Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, the federal district court has rejected the plaintiffs’ request for a preliminary injunction, which would have required the state government to continue contracting with discriminatory child welfare agencies. The court has so far held that enforcing the nondiscrimination terms of Philadelphia’s contract with the agency did not violate the agency’s rights and that the agency was unlikely to win on its First Amendment retaliation claim.55 Marouf v. Azar is still awaiting a response from the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.56 As these fights play out in the courts, the child welfare crisis continues.

Overburdened systems and the costs of discrimination

The rise in religious exemption laws comes at a time when state child welfare systems are facing ever-increasing numbers of children entering foster care. Prior to 2012, the number of children in foster care had been on the decline for 14 years.57 Since then, however, the number increased, rising more than 11 percent between 2012 and 2017, the most recent year for which national data are available.58 Many experts believe this number will only grow.59

There are several hypotheses for why the child welfare system has reached its current state. One clear contributor is the opioid epidemic, as children are removed from the homes of parents who are struggling with addiction. In 2016, more than one-third of removals involved drug abuse by a parent,60 an increase of nearly 50 percent since 2005.61 Some of the most pronounced increases in the number of children in foster care have occurred in states that have been hit hardest by the opioid epidemic.62 Cuts to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, which provides “assistance to families so that children ‘can be cared for in their own homes’ instead of in foster care,” have been cited as another contributor to the rising number of youth in care.63

There is a dearth of available families for children in foster care. A recent study of 34 states and Washington, D.C., revealed that between 2012 and 2017, the number of foster care beds available decreased in 14 states and increased in 20 states.64 Of the states where the number of available beds increased, however, more than half did not increase enough to keep up with demand.65 Overall, the foster care capacity in half of the states studied decreased since 2012, whether due to fewer beds, an influx of youth entering foster care, or both.66 Even in states such as Georgia, where the number of beds increased overall, there are still serious deficits in certain areas, and children may still struggle to be placed in their own communities.67 The turnover rate of foster parents ranges from 30 percent to 50 percent across the nation, and states are struggling with retention.68 Due to a lack of foster families, social workers are staying with children in hotels or having children sleep in their offices.69

In the HHS’ most recent Child and Family Services Review, it told 32 of 50 states that they need to improve in the areas of “Diligent Recruitment of Foster and Adoptive Parents.”70 As described above, same-sex couples are more likely than their peers to both foster and adopt children, and laws allowing for religious exemptions let child placing agencies turn away qualified LGBTQ prospective parents who would otherwise have provided a loving home for one or more children. As a result, foster youth remain in care longer, stressing an already stressed system.

Excluding LGBTQ prospective parents has economic costs

In 2016, roughly 20,532 children aged out of, or were emancipated from, foster care nationwide, while 57,208 children were adopted from foster care.71 These numbers have remained relatively constant over the past 10 years.72 Shrinking the pool of prospective parents by using a religious exemption or taking advantage of a state’s lack of LGBTQ-inclusive nondiscrimination laws covering prospective parents is not only an unjust result; it will also cost taxpayers money. For example, youth end up in group homes when there are insufficient foster family homes in which to place them.73 It costs states seven to 10 times more to place a foster youth in a group home rather than a foster family placement.74

Therefore, expanding the pool of adoptive parents by preventing discrimination will save government money. In addition to helping children achieve permanence with new families, adoptions from foster care save taxpayer dollars when compared with funding for children to remain in foster care. The largest portion of federal funding for child welfare comes from Title IV-E of the Social Security Act.75 It is difficult to calculate the average cost for all children in foster care due to, among other things, multiple funding streams from state and federal sources, as well as differences in how children in the system are classified. However, the HHS collects financial data from the states on total costs of maintenance payments and administrative costs for Title IV-E-eligible children, which can be used to make some rough calculations. Authors estimated an average cost of Title IV-E adoption assistance per child and an average cost of Title IV-E foster care per child. The goal was to calculate a rough estimate of taxpayer funds saved for each child adopted out of foster care, even if the child is eligible for an adoption subsidy.

Due to the complexity of child welfare funding and waivers, authors looked at the 2276 nonwaiver states for the most straightforward approximation of average spending for Title IV-E foster care. These states had 36,645 children eligible for Title IV-E foster care in 2016, based on average monthly estimates.77 The total federal and state/local costs for foster care maintenance payments and administrative costs for these children was $1.411 billion.78 The average cost per child was $38,513.79

By comparison, average monthly estimates indicate that there were 456,713 children eligible for Title IV-E adoption assistance in 2016.80 The total federal and state/local costs for adoption assistance payments and administrative costs for these Title IV-E-eligible children were $4.478 billion. The average cost per child was $9,804.81

Comparing the estimated annual per-child cost of a child receiving adoption assistance with the cost of maintaining a child in foster care, the child adopted from foster care costs the government only 25 percent as much as the child who remains in foster care.82 The difference in cost per child per year amounts to $28,709—$38,512 minus $9,804—or about $29,000. This per-child, per-year number is about $13,000 higher than a 2011 calculation that used somewhat similar methods.83

The money saved by moving a child who would otherwise remain in foster care to adoption is significant, even when including ongoing adoption assistance. Religious exemptions for child placing agencies, however, mean that there are fewer families available to adopt children from foster care. That, in turn, likely means more children are aging out of the foster care system without finding a permanent family, which will cost taxpayers a significant amount of money over the duration of the children’s time in care. If the child welfare system finds adoptive families for just 1,000 10-year-old children who would otherwise have aged out of foster care at 18, a rough estimate suggests it would save $230 million of taxpayer money over eight years.84

Case studies: Child placing agencies in Michigan and Texas

Michigan and Texas are two of the 10 states with laws that explicitly allow child welfare providers to turn away qualified prospective parents if working with them would conflict with agency leaders’ religious beliefs. These states also exemplify the capacity problem of child welfare agencies across the nation, highlighting the concern of limiting the pool of qualified parents through use of religious exemptions.

In Texas, the number of foster and adoptive homes working with licensed child placing agencies has decreased 39 percent—from 2,205 in fiscal year 2012 to 1,586 in fiscal year 2017.85 In April 2018, as many as 50 youth in foster care slept in the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services’ Child Protective Services offices, in hotels, and in shelters for at least two consecutive nights while waiting for placement.86 Michigan is facing similar problems: Its total number of beds available to children in foster care has decreased about 21 percent, from 16,181 in fiscal year 2012 to 12,861 in fiscal year 2017.87 The number of licensed Michigan foster homes has decreased 14 percent, from 7,062 on September 30 of fiscal year 2012 to 6,079 on September 30 of fiscal year 2016.88 At the end of fiscal year 2016, Michigan retained only 68 percent of the licensed foster homes it had at the beginning of the fiscal year.89

In both states, the percentages of children who spend two or more years in foster care are above the national average. Nationwide, 28 percent of youth had been in foster care for two or more years in fiscal year 2016.90 In that same period, 38 percent of Texas youth and 52 percent of Michigan youth had been in care for two or more years.91

Michigan has had a religious exemption law for child placing agencies since 2015.92 It is sweeping in scope, allowing agencies to turn away not only prospective parents to whom they religiously object but also children against whom they hold these objections.93 Texas has had a religious exemption law for child placing agencies since 2017.94 Its law goes even further than Michigan’s, broadly defining the child welfare services to which it allows its exemption to apply, including, family reunification services, residential care and groups homes, and counseling for children and families.95 In addition, both Michigan and Texas are lacking statutory nondiscrimination protections for prospective parents who identify as LGBTQ.

To more fully understand the risks associated with these laws, the authors conducted case studies of Texas and Michigan using a multimethod approach. Data were collected from publicly available child placing agency websites, as well as from phone calls and email surveys sent to individual agencies. (for more information, see the Methodology) Specifically, this research was undertaken to understand:

- Agencies’ nondiscrimination policies and procedures

- The relationship between an agency identifying as a faith-based organization and the risk of that agency discriminating against LGBTQ people and single adults

- The risks of lacking access to welcoming agencies due to geography

Analysis of agency websites

While the state laws in Michigan and Texas allow for discrimination against prospective parents who identify as LGBTQ, individual agencies have taken steps to indicate their willingness to work with LGBTQ people, including having a sexual orientation- and/or gender identity-inclusive nondiscrimination policy posted on their website. And although some agencies may publicly identify themselves as being faith-based or adhering to certain religious principles, they may also have inclusive policies. As many prospective foster and adoptive parents likely use websites to identify agencies with which they’d like to work, the authors undertook an analysis of available websites for agencies in both Texas and Michigan in order to ascertain what information is publicly available about the agencies’ nondiscrimination policies, as well as available signs of LGBTQ inclusion and statements of faith.

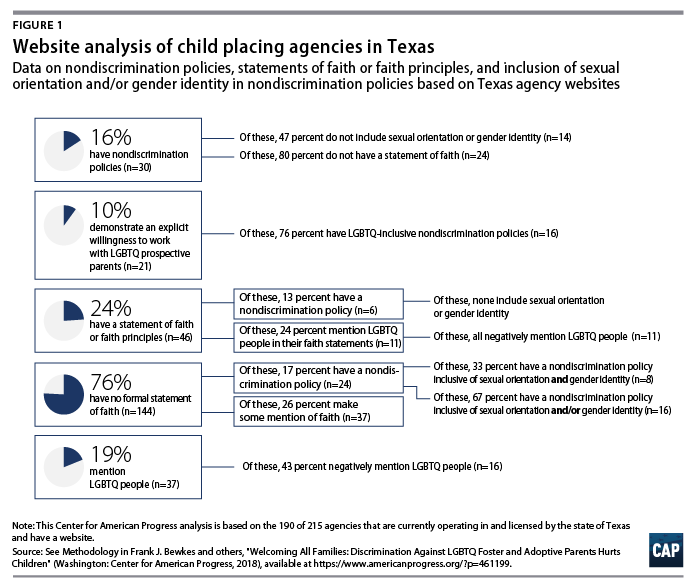

Texas

Texas has 215 unique, state-licensed child placing agencies currently in operation providing foster or adoption services;96 190 of these had websites available for analysis. For the purpose of this analysis, agencies that fell under the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services and that had the same website were merged. Among the agencies with unique websites—190—only 16 percent have posted nondiscrimination policies online. A review of those policies demonstrated that 47 percent did not include protections based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity. A greater number of agencies, 24 percent, had a statement of faith or a set of faith principles available on their website. Of those statements, 24 percent included a reference to sexual orientation and/or gender identity, and every one of those references was negative. Of agencies without a formal statement of faith, 26 percent made some mention of faith on their websites. This means that on the whole, 44 percent of licensed child welfare facilities in Texas either mentioned faith principles on their website or posted a formal statement of faith.97

In comparison, only 19 percent of websites, including those that made mention in statements of faith, mentioned LGBTQ people, sexual orientation, or gender identity; 43 percent of those mentions were negative. Overall, only 10 percent of Texas agency websites analyzed in this report showed their explicit willingness to work with LGBTQ prospective parents—either through a nondiscrimination policy inclusive of sexual orientation and/or gender identity, or through positive mentions of sexual orientation and/or gender identity.98

Nondiscrimination statements were more common for agencies that did not have a statement of faith on their site; 17 percent of agencies with no statement of faith had a nondiscrimination policy available, compared with 13 percent of agencies that had a posted statement of faith. Viewed another way, of agencies with a nondiscrimination policy, 80 percent did not have a statement of faith. None of the agencies with a statement of faith had a nondiscrimination policy inclusive of either sexual orientation or gender identity.99

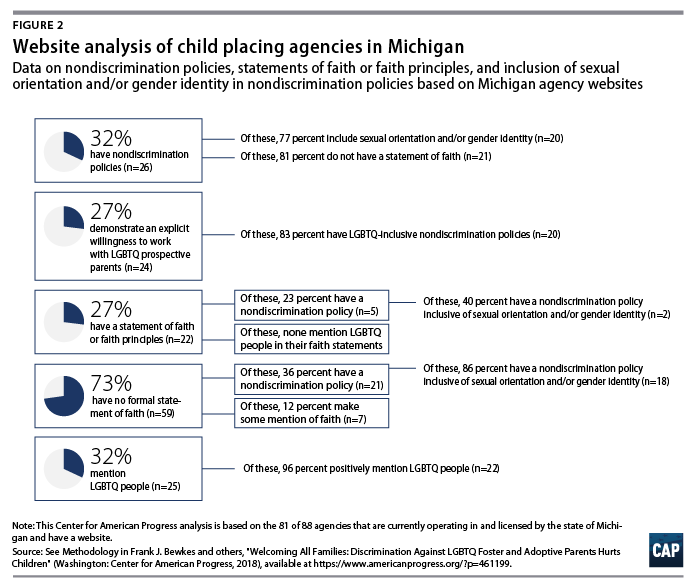

Michigan

Michigan has 88 unique entities currently operating and licensed by the state to provide foster or adoption services, 81 of which had websites available for analysis. As with Texas, agencies that were under the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and utilized the same website were counted as one agency. Among agencies with websites, 32 percent had nondiscrimination policies available online, and 77 percent of these policies included sexual orientation and/or gender identity.100 A formal statement of faith or set of faith principles was posted on 27 percent of agency websites. None of those statements included a mention of sexual orientation and/or gender identity. An additional 12 percent of agencies made some mention of faith on their websites that did not amount to a formal statement. In comparison, 32 percent of websites overall mentioned LGBTQ people or sexual orientation or gender identity, and nearly all of those mentions—96 percent—were positive.

Only 27 percent of Michigan agency websites stated the agencies’ explicit willingness to work with LGBTQ prospective parents through either a nondiscrimination policy inclusive of sexual orientation and/or gender identity or positive mentions of sexual orientation and/or gender identity. More than one-third, or 36 percent, of agencies in Michigan without a statement of faith had a nondiscrimination policy available on their website, and 86 percent of those agencies had a policy inclusive of sexual orientation and/or gender identity. All told, among agencies that posted a nondiscrimination policy, 81 percent did not have a statement of faith. In comparison, 23 percent of agencies with a statement of faith had a nondiscrimination policy of any kind available on their website, and 40 percent of those agencies had a nondiscrimination policy that was inclusive of sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

Overall conclusions from the website analyses

Reviewing the combined website data from both states, the number of agencies with nondiscrimination policies on their websites is relatively low, and only a portion of these policies are inclusive of sexual orientation and/or gender identity. There is a clear association between an agency website having a nondiscrimination policy and being secular. In Texas, there is also an association between having a statement of faith and both lacking a nondiscrimination policy and being overtly unwelcoming to LGBTQ prospective parents. In Texas and Michigan, the overall number of agency websites with features indicating that the agencies are welcoming to LGBTQ prospective parents was low: Less than a third of all agency websites had these features. Given this landscape, and the religious exemptions and lack of legal protections in both states, prospective parent may understandably become discouraged about finding a welcoming agency and choose to abandon their efforts.

Analysis of survey sent to Texas agencies

The authors also surveyed child placing agencies in Texas—including those considered in the website analysis as well as agencies without websites—either by telephone call or online survey, about their agency’s policies and practices. (for more information, see Methodology) Unique Michigan agencies for whom email information was available, 72, were also sent the survey, but only two agencies provided information following two email prompts. The state was thus dropped from the survey portion of the analysis. Among Texas agencies that were contacted by phone—128—26 completed the survey, 13 were unreachable due to an out-of-service phone number, 13 refused to participate in the research, and four did not answer enough of the survey to be considered for analysis. Another 11 agencies provided data via the online survey, with seven agencies providing enough data to be considered for analysis. Including phone and online surveys, 33 agencies provided enough information for analysis. Because this is a small number, the findings below should not be read as a representative sample of child welfare agencies in Texas. Data are presented here simply to provide additional information about the potential experiences of LGBTQ people in Texas who wish to become foster or adoptive parents.

Agency characteristics

The 33 survey respondents represent approximately 14 percent of the total number of licensed child placing entities in Texas. As with the website analysis, of particular interest to this case study was whether an agency described itself as being religious in nature. Of responding agencies, 70 percent, or 23, said that they were a secular institution while 28 percent—nine agencies—said that they were religiously affiliated. One respondent stated that they were not sure whether the agency was secular or religiously affiliated.

When asked whether their agency had a statement of faith or religious principles, 44 percent of religious agencies, or four, reported that they had such a statement, while one respondent was not sure whether the agency did or did not have this kind of statement. Website analyses indicate that overall, 24 percent of all child welfare agencies with websites in Texas had a formal statement of faith or religious principles, so the faith statement percentage obtained via self-reporting in the survey is likely an overestimate.

Agency policies and procedures

When asked if their agency had a nondiscrimination policy, 88 percent of respondents, or 29, indicated that their agency did. One respondent was unsure whether the agency had such a policy. Of agencies reporting that they did have a policy, 89 percent, or 25, said that this policy was inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity. The agency nondiscrimination policies covered only prospective parents 7 percent of the time, or two agencies, while another 7 percent covered only youth in care. Seventy-two percent, or 21 agencies, covered both youth and prospective parents. One respondent said that the policy did not cover youth or prospective parents; one respondent refused to answer the question; and two respondents were not sure what their nondiscrimination policy covered.

Among the religiously affiliated agencies, when asked whether the agency had ever referred prospective parents to another agency because of a conflict with faith or religious principles, 25 percent of, or two, respondents indicated that their agency had done so in the past. When asked specifically whether the agency had referred LGBTQ prospective parents because of such a conflict, neither agency said that they had done so.

Agencies were also asked whether they had ever worked with LGBTQ prospective families and single parents or would work with them in the future. Among responding agencies, 73 percent, or 24 agencies, said that they had worked with an LGBTQ family, and 88 percent—29—said that they had worked with a single prospective parent. Among agencies that had not yet worked with LGBTQ or single parents, 63 percent of, or five, respondents said that their agency would work with LGBTQ families in the future, while none of them said that they would work with single prospective parents in the future. Nearly 79 percent of respondents, or 26, said that their agency conducts outreach to prospective parents; of those, 58 percent—15 agencies—said that they actively recruit same-sex couples to be foster or adoptive parents. The survey data for Texas describe a more welcoming environment for LGBTQ prospective parents than the website analysis suggests. Importantly, however, survey respondents are a small proportion of the total number of agencies in the state, and these data do not provide a representative picture. It is a likely possibility that the respondents who agreed to take part in this survey and completed questions that were explicitly about LGBTQ prospective parents are more supportive of LGBTQ people than those who refused to take part in the survey or did not answer these specific items.

Government discrimination prevents affirming agencies from serving everyone

Government-sanctioned discrimination can prevent even LGBTQ-affirming agencies from being able to serve everyone equally. One agency that responded to the phone survey was LGBTQ-affirming in almost every way: They have a sexual orientation- and gender identity-inclusive nondiscrimination policy covering prospective parents; they actively recruit same-sex couples; and they have worked with same-sex couples and transgender parents in the past. They even reported that about 10 percent to 20 percent of the couples they serve are same-sex couples. However, that same agency reported that they actively avoid placing children with same-sex couples in certain regions of the state, because they know judges in those regions consistently deny permanent placements with same-sex couples.

While this agency supports LGBTQ families, its first priority is to secure permanent placements for the youth in their care, so they ultimately engage in pre-emptive discrimination against same-sex couples in some parts of the state. This clearly causes tension for the agency, whose respondent said during the survey, “We don’t want it to be about their sexual orientation, it should be about the care they provide for the child.”101 Contradicting the conservative argument that the private market can provide options for same-sex couples in the event that the state government endorses discrimination, such as by passing religious exemptions for child placing agencies, LGBTQ-affirming agencies cannot always freely serve everyone. Government discrimination can impede the ability of well-intentioned, accepting agencies to serve everyone while also limiting their ability to find as many loving, stable homes for children as they can.

Potential confusion for prospective parents

Discrepancies between the website review and the survey data suggest that the landscape is likely to be confusing for LGBTQ prospective parents living in states such as Texas, which has had high-profile debates about religious exemptions. Some agencies, for example, reported having an LGBTQ-inclusive nondiscrimination policy through the online or phone surveys even though they do not have one posted on their website. Others reported lacking an explicit LGBTQ nondiscrimination policy but also reported a history of working with LGBTQ prospective parents or a willingness to work with LGBTQ prospective parents in the future.

Interactions with staff during the phone survey process also help illustrate the complexity of LGBTQ-inclusive child welfare services in the state of Texas. Some agencies affirmatively expressed a desire to include LGBTQ people in their efforts to find permanent homes for children, such as one agency staff member who had just been hired at the time of the call, because the agency wanted to focus more on recruiting same-sex couples as prospective parents. Another agency staff member commented that it made her “angry” to see agencies turn away same-sex couples, saying it should not matter if someone is LGBTQ if they could offer a loving home.

However, evidence of a potentially discriminatory environment was also present. One staff member stated that the agency had not referred same-sex couples to another agency while they had been employed there, because these couples do not inquire about services; the staff person noted that the name of the organization, which was religious in nature, was a “dead giveaway” and that same-sex couples would likely know not to come. Another call offered other evidence that LGBTQ people or same-sex couples wishing to foster or adopt might steer clear of certain agencies. Although the authors were not able to speak directly with agency staff, the agency’s voicemail greeting included telling callers to “have a blessed day.” Absent any other information about this agency—its website did not have a nondiscrimination policy available—an LGBTQ prospective parent might assume “blessed” is a religious term and choose to avoid the agency for fear of discrimination.

Access to LGBTQ-inclusive services and protections by geographic region

Both website and survey data indicate wide variation across Texas and Michigan in the ability of an LGBTQ person or same-sex couple to access child welfare services that are more likely to be welcoming and offer inclusive nondiscrimination protections. To explore the issue of access further, analyses were conducted to look at the concentration of LGBTQ-inclusive or potentially noninclusive agencies by geographic region. To conduct these analyses, authors used website data only, as these data present a more complete picture of the agencies across each state than the survey data. In the present analysis, agencies that reported inclusive policies or practices during surveys but that did not have an explicit policy listed on their website were not deemed a “welcoming agency.” In designating an agency as welcoming or unwelcoming, the authors assumed that the information an agency posts on its website is more likely to be the official policy, regardless of information reported by a staff member in the survey. Websites represent a main entry point for how prospective parents can evaluate whether an agency is one that would work with them.

The website analysis for Texas agencies spanned 54 counties, representing 21 percent of the total number of counties in the state. The analysis found that in 13 of those counties, 100 percent of agencies at least mentioned faith on their websites or had a more formal statement of faith or religious principles. At least 50 percent of agencies did so in 24 of the counties. Eight counties had at least one agency that listed a nondiscrimination policy on their website with reference to sexual orientation and gender identity, while 10 counties had agencies with a nondiscrimination policy with reference to either sexual orientation or gender identity. In six counties, 100 percent of the agencies that mention LGBTQ people at all reference them in a negative way. In 11 counties, at least 50 percent or more of the agencies mention LGBTQ people in a negative way.

The analysis of Michigan’s agencies spanned 68 counties, or 82 percent of counties in the state. In two of these counties, the analysis found that 100 percent of agencies have at least a mention of faith on their website or make available a statement of faith or religious principles. In 17 counties, at least 50 percent of agencies have these formal or informal indicators of being faith-based. Sixty-five counties include agencies with nondiscrimination policies that include sexual orientation and gender identity on their websites, and seven of these counties also have agencies with only sexual orientation nondiscrimination protections. Among the counties with agencies that mention LGBTQ people or sexual orientation and gender identity at all, 99 percent of them refer to LGBTQ people positively.

Agencies that welcome all families are not necessarily accessible for all families

Texas is a large state with few agencies that are inclusive of LGBTQ families. For these reasons, the authors conducted an analysis of the geographic accessibility of welcoming Texas child placing agencies. As the Texas map illustrates, prospective parents in many parts of Texas live far away from the nearest LGBTQ-inclusive agency. The present analysis sought to determine in real terms the burden on LGBTQ people seeking to foster or adopt. Distances to the nearest child placing agency with a nondiscrimination policy explicitly inclusive of LGBTQ people were calculated using Google Maps. In three of the 10 most populous cities of Texas, there is no agency that is explicitly affirming of LGBTQ people within the greater metropolitan region. A same-sex couple in El Paso might avoid the nearest agency one mile away for fear of being turned away, and instead drive 348 miles to an agency with an LGBTQ-inclusive nondiscrimination policy on their website. Similarly, there are child-placing agencies within 30 miles of Corpus Christi and within four miles of Laredo, but the nearest agencies that explicitly welcome LGBTQ people by having an LGBTQ-inclusive nondiscrimination policy posted on their websites are 67 and 153 miles away, respectively.

The distance to a welcoming agency can be especially pertinent in areas with a high concentration of LGBTQ families. For half of the 10 Texas counties with the highest concentration of same-sex couples—Hays, Aransas, Henderson, Williamson, and Caldwell—the nearest agency is not LGBTQ-inclusive.102 Rather than risk being turned away at a closer agency, a same-sex couple in Henderson County, for example, may travel twice as far as a different-sex couple to the nearest explicitly welcoming child placing agency—85 miles rather than 41 miles. (see Methodology for more details)

Recommendations

Below are some steps that the federal government, state governments, and state licensed child placing agencies can take to ensure that pools of qualified prospective parents include those who are LGBTQ.

Enact nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ prospective parents and repeal religious exemptions for child placing agencies

In the absence of federal protection and given the lack of protections in the vast majority of states, the landscape looks bleak for prospective LGBTQ parents. State legislatures should pass into law explicit nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ prospective parents—both adoptive and foster. Enactment and rollout of these protections should include trainings for child placing agencies on how to be welcoming to all prospective parents, including those who are LGBTQ. Nondiscrimination protections will likely increase LGBTQ engagement with adoption and fostering, leading to more families for youth in care.

Religious exemptions for child placing agencies, on the other hand, are counterproductive to the rights of LGBTQ prospective parents as well as the interests of the nearly half-million youth currently in foster care. They must be repealed in the 10 states with such explicit exemption laws.

At the federal level, Congress should enact a law, such as the Every Child Deserves a Family Act,103 that explicitly prohibits state-licensed child placing agencies that receive federal funding, or that contract with those that do, from discriminating against or turning away qualified LGBTQ prospective foster or adoptive parents.

Agencies that welcome all families need to make their policies explicit

To eliminate any ambiguity or confusion, agencies that are welcoming to LGBTQ prospective foster and adoptive parents should explicitly advertise themselves as such. This will likely increase LGBTQ prospective parents’ engagement with fostering and adoption. From the case studies above, it appears that many more agencies either need to adopt nondiscrimination policies that are inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity or need to post their existing policy on their website. The need to post existing policies online is especially true for agencies that are welcoming to LGBTQ prospective parents. Given the increasing number of states with religious exemptions for child placing agencies, the default assumption of some LGBTQ parents may be that an agency is not welcoming, especially if that agency is faith-based. Indeed, the case studies showed that faith-based child welfare agencies are less likely than secular agencies to have an inclusive nondiscrimination policy on their websites. This does not necessarily mean that they are unwelcoming, but it likely sparks doubt for some prospective parents who might then avoid such agencies—an unfortunate possible result. While the number of faith-based agencies that are welcoming should certainly increase, those that already are welcoming should be celebrated. Samaritas, for example, is a Lutheran child placing agency “dedicated to helping those in need regardless of … sexual orientation” and meeting “spiritual needs” through its programs.104

Furthermore, the number of agencies with posted sexual orientation- and gender identity-inclusive nondiscrimination policies is low overall, as is the number of explicitly welcoming agency websites. This lack of welcoming policies and messages likely discourages some LGBTQ prospective parents and might lead them to believe they will experience discrimination.

Encourage more recruitment of and outreach to all prospective parents

State departments of children and families and the child placing agencies they license should increase their foster and adoptive family recruitment efforts, including within the LGBTQ community. The HHS’ periodic review of state child welfare systems found that the “Diligent Recruitment of Foster and Adoptive Homes” in 32 states “Needs Improvement.”105 Given the current stresses on states’ child welfare systems, this is unacceptable. Increasing outreach and recruitment in the LGBTQ community, especially given its disproportionate engagement in adoption and fostering, would be a step in the right direction.

Conclusion

The United States is facing a child welfare crisis, and willing and qualified foster or adoptive parents are sorely needed. Turning away LGBTQ prospective parents by asserting a religious exemption or taking advantage of a lack of state nondiscrimination law is a violation of this group’s rights. It also negatively affects the already strained child welfare system, ultimately harming the children in its care.

The goal of every state’s child welfare system should be welcoming all families in order to place children with families who can best meet their needs. This is not only the right thing to do for children and parents, but it also saves governments money. Indeed, states have an economic interest in enabling more children to be adopted out of foster care when they cannot return home or be placed with relatives. The authors’ estimates suggest that each child adopted from foster care, even with adoption assistance support, reduces state and federal spending by almost $29,000 annually when compared with those children who remain in foster care.106

LGBTQ parents cannot solve the child welfare crisis on their own, but they can certainly help. The nation owes it to the young people in care to give them every chance possible at finding a permanent family.

About the authors

Frank J. Bewkes is a policy analyst for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. He leads state-level engagement for the team and focuses on LGBTQ family law and policy. Prior to joining the Center, he had previously worked for such organizations as the American Civil Liberties Union, the Family Equality Council, the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute, and the Brennan Center for Justice. Bewkes holds a Master of Laws from New York University School of Law and a J.D. from George Washington University Law School, where he was awarded the Thurgood Marshall Civil Liberties Award. He earned his Bachelor of Arts in political science at Yale University. He is also currently an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.

Shabab Ahmed Mirza is a research assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress, where she works on homelessness and housing policy; data collection on sexual orientation and gender identity; and the impact of anti-LGBTQ discrimination. Her work has been cited in Time, Forbes, NPR, and other publications. Previously, she worked at the National Center for Transgender Equality and was a Young Leaders Institute Fellow at South Asian Americans Leading Together. Mirza received a bachelor’s degree from Reed College and an associate degree from Portland Community College. She is from Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Caitlin Rooney is a research assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. She wrote her senior honors thesis on international advocacy for LGBT rights and presented it at the Western States Communication Association Undergraduate Scholars Research Conference. She has interned at the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania and for Pennsylvania state Rep. Brian Sims (D), the first openly gay member of the Pennsylvania Legislature. Prior to joining the Center, Rooney volunteered for the Pennsylvania Prison Society as a lobbyist assistant. Rooney holds a bachelor’s degree in legal and political rhetoric with a minor in politics from Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington.

Laura E. Durso is vice president of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. Using public health and intersectional frameworks, she focuses on the health and well-being of LGBT communities; data collection on sexual orientation and gender identity; and improving the social and economic status of LGBT people through public policy. Prior to joining the Center, Durso was a public policy fellow at the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, where she conducted research on LGBT homelessness and at-risk youth, poor and low-income LGBT people, and the business impact of LGBT-supportive policies. She holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Harvard University and master’s degree and a doctorate in clinical psychology from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.

Joe Kroll is the former executive director of the North American Council on Adoptable Children (NACAC), a position he held from 1985 to 2015. In retirement, he has served twice as the interim director of Voice for Adoption, which NACAC helped found in 1995.

Elly Wong is a former intern with the LGBT Research and Communications team at the Center for American Progress. They have previously done work with the Burton Blatt Institute on workplace discrimination and the Center on Human Policy on community participation for people with disabilities. They are a student at Syracuse University majoring in policy studies and citizenship and civic engagement, with a minor in disability studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank their report partners, Voice for Adoption and the North American Council on Adoptable Children, for collaborating on and co-branding this report. They also thank Family Equality Council, who partnered with them on collecting stories for this report and other products on this increasingly important issue.

Most especially, the authors wish to thank the following individuals who significantly contributed to the research, drafting, and/or review of this report: Mary Boo, Schylar Baber, Cortney Jones, Gabriel Lewis, Adam Cetorelli, Charlie Whittington, Rachel Koehler, Claire Markham, Emily London, Sharita Gruberg, Bronte Forsgren, Erin Elms, Michael Tuskey, and Emilie Stoltzfus.

Finally, they extend their deep appreciation to their storytellers, John Freml and Thomas H., who shared their stories and trusted the authors with them.

Methodology

The authors gathered and analyzed data on Texas and Michigan child placing agencies through a review of agency websites and a survey fielded to the agencies.

Website analysis

To identify child welfare facilities licensed by the states of Texas and Michigan, data were gathered from the websites of the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services in June 2018.107 Agencies that do not place children in either foster care or adoptive settings were excluded. In Michigan, only facilities designated by the state as child placing agencies were included for further investigation. In Texas, a list of child welfare agencies that do adoption placements and a list of child welfare agencies that do foster care placements were combined, and duplicates were removed so that agencies that do both only appeared once.

Researchers entered facility names into search engines to find agency websites. If a website matching the agency name and location did not appear within the first two pages of results, or if the website did not load due to technical errors, the agency was considered as not having a website.

Website subpages with descriptions of the agencies and information on fostering or adopting were read thoroughly in order to determine if the site had a nondiscrimination policy; a statement of faith or faith connection; or mentions of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). A website was counted as having a nondiscrimination policy if it had a statement of not discriminating against specific groups or based on specific characteristics such as race or income. A nondiscrimination policy was counted as including sexual orientation if it contained the words “sexual orientation” or similar terms; it was counted as including gender identity if it contained the words “gender identity” or similar; and it was counted as including both sexual orientation and gender identity if it contained the term “LGBT” or similar terms. A website was counted as having a statement of faith if the agency professed a specific religious belief or included quotations from religious texts. If the website did not profess a specific religious belief but indicated spirituality or connection to a faith, the agency was designated as having a faith connection. An agency was designated as mentioning sexual orientation or gender identity negatively if its statement of faith specifically mentioned being against SOGI; if the website mentioned that the agency does not serve LGBTQ people; or if the website stated that the agency only serves couples consisting of a husband and a wife, which discriminates against same-sex couples. An agency was designated as mentioning SOGI positively if its nondiscrimination policy included SOGI, if it explicitly stated that it served LGBTQ people, or if same-sex couples were featured on the website. Related keywords such as “nondiscrimination,” “sexual orientation,” and “faith” were searched via Google’s website search function if nondiscrimination, faith, and SOGI information could not be found on description or foster/adopt subpages, and websites were marked as not having this information if no relevant results were found.

A Michigan entity was determined to be a branch if it shared a licensee name with another entity. A Texas agency was determined to be a branch if it was designated as a branch by the state and had the same or similar name as another agency with which it also shared a website.

Geographic analyses

The geographic analysis considered all agency locations, including branches. The 10 largest cities in Texas were determined from 2010 U.S. census population data. The 10 counties with the largest concentrations of same-sex couples were determined based on analysis of 2010 U.S. census data by the Williams Institute, the most recent year for which data were available.108 Distances used in the analysis are the shortest driving distance to the nearest agency, which the authors determined using Google Maps. Distances were calculated from downtown El Paso and from Rockport, as these neighborhoods were named in the entries for El Paso109 and Corpus Christi,110 respectively, on GayRealEstate.com as having large concentrations of LGBTQ residents. The default location on Google Maps for Laredo, Texas, was used, since Laredo did not have a particular neighborhood listed on the website. Default locations on Google Maps were also used for each of the counties.

Phone and web survey

To gather additional data directly from agency staff, authors crafted a phone interview survey script that included questions around the policies and practices of the various agencies.111 To field the phone survey, researchers used the previously compiled lists of unique child placing entities in Texas. The state has a large child welfare system and recently passed a religious exemption law,112 making the issue potentially more salient for agency staff and more identifiable through a phone survey. Agency contacts were determined by searching through staff pages to find a caseworker supervisor, or other senior person if no caseworker supervisor was listed. If the identified person had a phone number and email listed, that contact information was noted for the agency. If not, general agency contact information was noted.

The survey questions were fielded using the phone number provided by the state government or the phone number from the contact information found in the authors’ website analysis if the first number was either missing or incorrect. Agencies were called twice. For agencies that did not respond, voicemails were left for staff requesting a callback. CAP employees shared who they were, that CAP was conducting the research, and their intention to use the survey data to inform policy. So as not to influence responses, respondents were not explicitly informed of CAP’s specific position on the issue of LGBTQ prospective parents fostering or adopting but were told that information is publicly available. After calling 128 agencies, authors had made direct contact with a staff member at 52 agencies, representing 24 percent of the total number of unique agencies in Texas. Given the high rate of incomplete calls and the time=intensive nature of this method of data collection, an online survey was constructed to mirror the phone survey and attempt to reach the remaining agencies. For this same reason, the phone survey was not fielded to Michigan agencies. The authors also hypothesized that an online survey format might incentivize responses from agency staff who wished to have more privacy in responding and who needed time to gather information to accurately respond to questions. The authors fielded the web survey via Survey Monkey to Texas agencies that had not been successfully contacted by phone. The possibility of winning one of 100 $20 gift cards was offered as an incentive for participation. Web survey results and phone survey results were analyzed together. In total, seven agencies completed the online survey, bringing the total number of agencies that provided enough data for analysis to 33.

The unique Michigan agencies for whom email information was available, 72, were also sent the web survey, but only two agencies provided information following two email prompts. The state was thus dropped from this analysis.