After six years and nearly 25,000 public comments, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a rule in May 2016 to implement Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), clarifying that discrimination based on sex stereotyping and gender identity is impermissible sex discrimination under the law.1 This position was in line with growing case law to support prohibitions against sex discrimination covering LGBTQ people.2

In December 2016, however, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas issued a nationwide injunction prohibiting HHS from enforcing the regulation’s prohibition on discrimination on the basis of gender identity, and, to date, the current administration has failed to defend the regulation.

Franciscan Health, formerly Franciscan Alliance Inc., is a religiously affiliated health care alliance. Along with eight states and two other private health care providers, it sued HHS over the regulation.3 They alleged that doctors would be forced against their will to perform medical procedures that are contrary to their religious beliefs and that they believe are harmful to the patient. Most specifically, they objected to providing medical treatments related to gender transition, especially for children. The rule implementing Section 1557 requires providers to offer medically necessary health care services to transgender people if those services are within their scope of practice. Franciscan Alliance claimed that following their beliefs and performing procedures for some people, such as mastectomies for cancer patients, but not others, such as “top surgery” for transgender patients, would open them to liability. Due to this concern, they even went so far as to claim that doctors would be forced to cease providing certain medical care treatments for all patients in order to exempt themselves from providing transition-related care to which they have a religious objection.

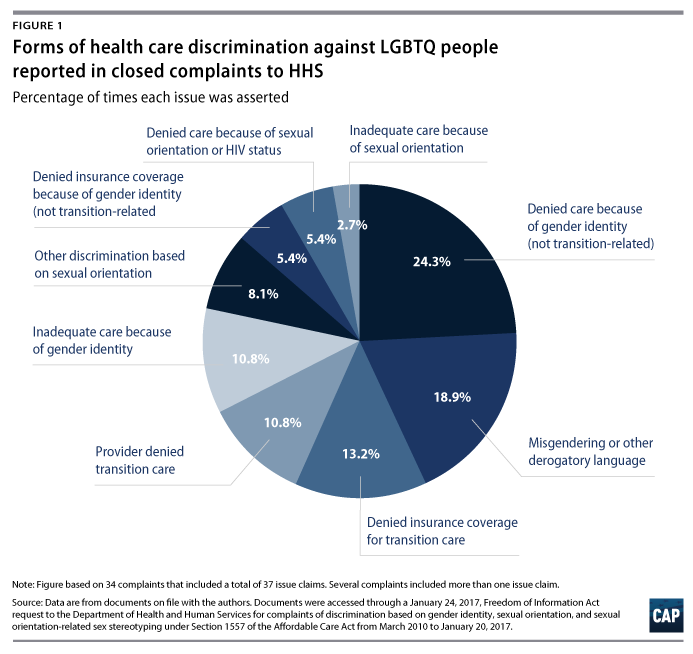

To learn more about the nature of anti-LGBTQ discrimination in health care and HHS’s enforcement of Section 1557’s protections for LGBTQ people, the Center for American Progress conducted an analysis of closed complaints of discrimination based on sexual orientation, sex stereotyping related to sexual orientation, and gender identity. HHS received these complaints prior to the injunction. The analysis revealed that the majority of patients who filed such complaints of discrimination with HHS had not been denied care related to gender transition. Rather, transgender patients who filed complaints were often denied in general, unrelated to transition-related treatments, solely because of their gender identity.

This finding is significant, because Franciscan Alliance’s stated concern in Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell is that the implementation of Section 1557 would force its doctors to help patients with gender transition care. But the data show that health care providers most often discriminate against transgender people simply for being who they are—not based on the care they need. With the majority of discrimination complaints grounded in gender identity rather than gender transition, the desire of opponents—including Franciscan Alliance—to undo Section 1557’s protections for transgender people would have sweeping consequences and possibly indicates an underlying animus toward transgender people generally. CAP’s analysis of these claims indicates that, if successful for Franciscan Alliance, Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell’s attack on gender identity discrimination protections would allow many forms of discrimination against patients—such as refusing to use proper pronouns and to provide reproductive health care simply because a person’s gender presentation does not match their ID or records—and undermine the quality of care for many people while increasing litigation costs for providers.

Thankfully, a different federal court ruled in September 2017 that discrimination on the basis of gender identity is sex discrimination prohibited under Section 1557 itself.4 This ruling affirmed that transgender individuals can go directly to court, rather than file gender identity discrimination complaints through the administrative procedures of the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) at HHS.5 Since gender identity discrimination is prohibited sex discrimination under the ACA itself, the administration should not amend the rule interpreting Section 1557 in response to Franciscan Alliance; to the contrary, it should continue to defend the rule and fight to overturn the injunction.

Section 1557’s nondiscrimination protections

Section 1557 prohibits discrimination by any health program or activity receiving federal assistance; health programs and activities administered by HHS; and marketplaces under the ACA, on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability.6 The definition of what constitutes sex discrimination in Section 1557 is informed by the prohibitions against sex discrimination in Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, as well as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.7 The courts have clarified that discrimination on the basis of gender identity is sex discrimination, despite the stance of the Trump administration.8 In other words, as a federal court recently found, “Because Title VII, and by extension Title IX, recognize that discrimination on the basis of transgender identity is discrimination on the basis of sex, the Court interprets the ACA to afford the same protections.”9 (see text box) The ACA offers protections regardless of the status of its implementing regulations.

Prescott v. Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego

In September 2017, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California ruled on Prescott v. Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, a case brought by a mother on behalf of her deceased transgender son.10 Kyler, her son, had battled with gender dysphoria, depression, and suicidal ideation. His mother sought help at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego (RCHSD), where hospital staff proceeded to repeatedly misgender Kyler. Unfortunately, RCHSD did not correct the behavior after it was brought to light by Kyler’s mother; instead, it discharged Kyler from psychiatric hold early. Kyler died by suicide a month later. The court’s ruling in this case was in response to an order on a motion to dismiss, so the merits of Kyler’s mother’s claim that her son was discriminated against were not addressed. The court did, however, hold that the discrimination claim based on Kyler’s transgender identity arose from the language of the ACA itself, rather than the implementing regulation, and that the claim was plausible.

To provide further clarity on the nature of the protections afforded by the ACA, HHS issued a rule that interpreted the sex discrimination prohibition in Section 1557 to prohibit discrimination based on sex stereotyping and gender identity.11 There is growing case law to support prohibitions against sex stereotyping, including sexual orientation discrimination.12 The rule specifies that insurers are prohibited from denying or limiting health insurance or coverage because of someone’s gender identity; that there cannot be a categorical exclusion from insurance coverage for transition-related care; and that if health services are ordinarily available to individuals of a certain sex, they cannot be denied to a transgender person for whom they are medically relevant. For example, a gynecologist cannot refuse to perform a Pap test or mammogram on a transgender man. The rule is in line with what the vast majority of insurers have already done. A 2017 study of 71 insurers in 18 states found that 90 percent of insurers did not include transgender-specific exclusions and nearly one-third affirmatively stated that medically necessary treatment for gender dysphoria is covered.13 The rule also clarifies that persistently and intentionally refusing to use a transgender person’s correct name and gender pronoun constitutes impermissible harassment on the basis of sex and that transgender people must have access to facilities and programs consistent with their gender identity.

The OCR is charged with accepting and investigating complaints under Section 1557. The statute also provides a private right of action, allowing individuals who experience discrimination to file a lawsuit under Section 1557.

Even without a formal finding of discrimination, the OCR can work with health care providers to take proactive steps to ensure LGBTQ patients are protected from discrimination like it did with The Brooklyn Hospital Center. In July 2015, the OCR reached a voluntary settlement agreement with The Brooklyn Hospital Center after a transgender woman filed a complaint with the office that the hospital violated Section 1557 when it assigned her to a double occupancy patient room with a man despite her gender identity.14 The hospital agreed to adopt new nondiscrimination policies and train employees on compliance with those policies.15

Analysis of sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination complaints under Section 1557

On January 24, 2017, CAP submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to HHS for complaints of discrimination based on gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexual orientation-related sex stereotyping under Section 1557 of the ACA from March 23, 2010, to January 20, 2017. In response, CAP received information about a subset of complaints that were received by the agency and were closed—a total of 34 complaints from 2012 through 2016. Review of the documents, however, indicated that the Brooklyn Hospital Center case was not among the complaints provided. These FOIA data do not reflect complaints that remain open or that have been held without action based on the Franciscan Alliance litigation. In the final rule interpreting Section 1557, HHS estimated that, each year, it receives a total of 15 to 20 Section 1557 complaints that cannot be filed under other statutes. HHS, however, predicted this number would increase following publication of the proposed rule.16 Among the complaints, which sometimes had more than one issue claim, there were 31 claims involving gender identity discrimination and six involving sexual orientation discrimination.17 In two instances, HHS completed its investigation and found the complaints were substantiated; in other words, HHS issued actual findings of discrimination. Most of the closed complaints resulted in the subject of the complaint taking voluntary corrective action. In 22 cases, the covered entity worked with HHS to institute trainings or change policies or HHS provided technical assistance to address the complaint.

Most complaints involved denials of care or insurance coverage because of a person’s gender identity

The most common complaints involved individuals being denied care because of their gender identity or transgender status. There were 13 such closed complaints among the 31 complaints involving gender identity discrimination that CAP reviewed. Complaints included a transgender woman being denied a mammogram because of her gender identity; transgender people being denied sexual assault medical forensic examinations; and a transgender man being refused a screening for a urinary tract infection because the clinic claimed it only provided those screenings to women.

One of the next most common complaints involved people being denied insurance coverage because of their gender identity. Five of these complaints were denials of coverage for transition-related care; however, there was one incident of an individual who was refused insurance coverage for reproductive health care because of his gender identity and another because the insurer would only cover genetic testing for breast cancer for women and not for a transgender man—despite the fact that the testing was recommended by the complainant’s doctor.

Additional examples of discrimination in the complaints include:18

- A transgender woman went to the hospital with cold symptoms, but her care was delayed because of repeated questions about her gender identity and inappropriate questions about her anatomy at intake.

- A transgender woman with a disability was repeatedly harassed by the driver of a medical transport service that took her to and from her doctor’s appointments.

- A woman was separated from her wife during an emergency room visit and her wife was not permitted to enter her room for more than two hours.

- While recovering from an appendectomy, the doctor treating a transgender woman refused to call her by the correct pronouns and said the doctor does not deal with “these kinds” of patients.19

Many complaints were resolved through voluntary corrective action rather than costly litigation

The plaintiffs in Franciscan Alliance claimed that they feared facing costly litigation as a result of the rule. However, what the available complaints show is that HHS overwhelmingly worked with the subject of the complaint to amend policies and implement trainings to teach staff how to treat transgender patients without discrimination, rather than taking them to court. This was true for all cases involving the misgendering of patients—seven of the 37 closed issue claims CAP reviewed—and for nearly all cases involving coverage or provision of transition-related care—11. HHS investigations had uncovered evidence to substantiate two of the complaints CAP obtained. In one of two complaints, a receptionist told a transgender person the clinic would not perform surgery because the “Lord does not approve.”20 After the complaint was filed and HHS investigated, the clinic offered to proceed with the surgery, updated its nondiscrimination policy, formulated new policies on transgender health care, and trained its staff on the policy. While the Franciscan Alliance litigation relied heavily on hypothetical scenarios—and misstatements of accepted medical standards of care—regarding transgender children, none of the complaints CAP reviewed involved transition-related care for a minor.21

Finally, beyond the outright denial of care, there were five complaints involving patients who alleged receiving substandard care because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. These involved situations where someone’s care was delayed or they were released from a hospital prematurely. In these instances, the subjects of the complaints took voluntary corrective action and trained their staff on nondiscrimination obligations under the law and LGBTQ cultural competency. There were also two complaints of people being treated differently because their spouse was the same sex. In these cases, the subjects of the complaints also voluntarily trained staff or changed their record-keeping policies to ensure all married couples were treated the same.

In the two instances CAP reviewed where the complaints were substantiated by HHS, the subjects of the complaints also took corrective actions. In addition to the case mentioned above, an individual was denied a flu shot because they were HIV-positive. In this case it was determined they were discriminated against on the basis of having a disability.

Finally, contrary to assertions made by the plaintiffs in Franciscan Alliance, in no case did HHS threaten to sue or withhold federal funding, nor did it order a health care professional to perform a service against their medical judgment.

Conclusion

Reviewing this subset of Section 1557 complaints resolved by HHS shows that the enforcement of the statute was working well to resolve very real issues of discrimination, and that the fears raised by the Franciscan Alliance lawsuit are not well-founded. Research shows that discrimination affects whether transgender people are able to receive timely, quality care, as well as the willingness of transgender people to seek care in the future. A survey by CAP found 23.5 percent of transgender respondents avoided doctor’s offices in the past year out of fear of facing discrimination.22 Robust enforcement of the ACA’s nondiscrimination protections reassures these Americans that they will not be refused for discriminatory reasons.

Contrary to the findings of the Texas court in Franciscan Alliance,23 Section 1557’s implementing rule simply creates a regulatory structure and administrative process for enforcing what the ACA already requires. A claim for anti-transgender discrimination already existed under the ACA. The implementing rule is important, because its administrative procedures enable victims to seek redress without the costs and time associated with litigation. The present analysis suggests that this process has often worked well for those who have availed themselves of it.

As Franciscan Alliance v. Burwell proceeds, the ACA’s protections remain in effect and continue to be critical for addressing the well-documented health disparities facing LGBTQ people.24 However, due to costs of litigation and the apparent success of the closed administrative claims, it is vital that the administrative process remain an avenue for addressing discrimination grievances. Unfortunately, HHS indicated in recent court filings that rather than preserving this critical mechanism for protecting LGBTQ people from discrimination, it is rewriting the rule and likely removing explicit protections for LGBTQ people.25 HHS also recently announced that it will open a separate civil rights office that is solely focused on defending religious refusals to provide health care. HHS’ recent actions do not signal a commitment to protecting all Americans’ access to care. Rather, they further underline the Trump administration’s commitment to undermining the basic rights, health, and well-being of LGBTQ people.26

Sharita Gruberg is the associate director of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. Frank J. Bewkes is a policy analyst for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Jocelyn Samuels, Sunu Chandy, Kelli Garcia, Harper Jean Tobin, Kellan Baker, and Katie Keith for reviewing and providing feedback on this issue brief.