During his first week in office, President Donald Trump issued an executive order1 setting the stage for more punitive and aggressive detention and deportation practices. Among other things, the executive order—“Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States”—called for a rapid expansion of harmful 287(g) agreements,2 through which state and local law enforcement personnel are deputized to enforce federal immigration laws. Since then, the number of local jurisdictions that have signed 287(g) memoranda of agreement (MOAs) with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has more than doubled.3 Today, there are 78 law enforcement agencies4 across 20 states participating in the 287(g) program and serving as a force multiplier in President Trump’s deportation force.

For years, jurisdictions participating in the 287(g) program have faced legal challenges resulting from allegations of racial profiling and civil rights abuses.5 In addition, they have come under serious criticism regarding financial mismanagement and for their role in facilitating the deportation of thousands6 of immigrant residents over traffic violations and other minor offenses in their communities. In 2010, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued a report7 that was deeply critical of ICE’s management and oversight of 287(g) programs and that raised concerns relating to poor compliance with the terms of the agreements, inadequate officer training,8 and a general lack of transparency and accountability.

Local oversight is key: 287(g) steering committees

When a local law enforcement agency (LEA) makes the voluntary decision to enter into a 287(g) agreement, it devotes staff and local resources to work in greater cooperation with ICE on immigration enforcement.9 In light of that partnership arrangement, it is in the best interest of the public to ensure that community leaders and other key constituencies have a meaningful opportunity to provide feedback to local officials about how such agreements are operating. Engaging regularly with local stakeholders can help ensure effective oversight, improve compliance with the terms of the MOA, and provide critically needed ongoing input in determining whether maintaining such an agreement with ICE is having a positive or negative impact on the community as a whole.

A key recommendation in the 2010 OIG report was that ICE “[r]equire 287(g) program sites to maintain steering committees with external stakeholders, with a focus on ensuring compliance with the MOA.”10 The OIG observed that prior to July 2009, MOAs required that ICE and the participating jurisdiction establish a steering committee to evaluate immigration enforcement actions but that few jurisdictions maintained such steering committees, and none required the participation of community stakeholders. In July 2009, ICE revised its template MOA, removing the steering committee requirement entirely. In its report, the OIG explained, “Steering committees should not be narrowly viewed as a means to enhance ICE and LEA communications, but as a way to (1) improve program oversight and direction, (2) identify issues and concerns regarding immigration enforcement activities, (3) increase transparency, and (4) offer stakeholders opportunities to communicate community-level perspectives.”

While ICE concurred with the OIG recommendation, the OIG chose to leave the recommendation unresolved and open because ICE’s response contained few specifics.11 Six months later, ICE committed to the OIG that it was “in the process of finalizing guidance to the LEAs to establish and implement steering committees with external stakeholders.”12

In 2017—seven years after the issuance of the OIG reports—Congress for the first time echoed the steering committee recommendation, directing ICE “to continue to require the establishment and regular use of steering committees for each [287(g)] jurisdiction, including the participation of external stakeholders.” The language was included in a House Appropriations Committee report for the fiscal year 2018 Department of Homeland Security appropriations bill,13 which was subsequently incorporated into the explanatory statement14 accompanying the bill enacted into law.*

The disappointing reality of steering committees in local communities

In 2010, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agreed to require local law enforcement agencies to establish and implement steering committees with external stakeholders. Despite that agreement and the recent congressional action directing ICE to establish steering committees, ICE and local jurisdictions alike have failed to comply with this key oversight requirement. Today, the standard memorandum of agreement between ICE and 287(g) LEAs does not specifically require participation from community stakeholders to provide advice and guidance on how the program is running. In fact, in recent years, the language included in 287(g) agreements requires local jurisdictions to participate in steering committee meetings “as necessary,”15 and it does nothing more than allow local officials to engage with members of the public at their own discretion.16

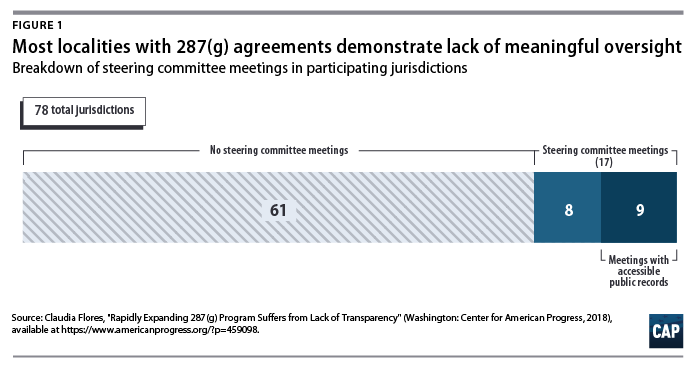

From July through September 2018, the Center for American Progress reached out to 78 localities with existing 287(g) agreements to examine when, if ever, steering committee meetings have taken place.17 The results were striking. Upon initial contact, not a single participating jurisdiction could provide information on whether it had established a steering committee or give details about when a stakeholder engagement meeting relating to a 287(g) program may have taken place. After conducting detailed internet searches that included reviewing LEAs’ social media accounts and local government websites, calling public information officers, and speaking with community groups in nearly a dozen states, CAP could only confirm that 17 jurisdictions have held steering committee meetings in recent years, and only 9 had public records of those meetings occurring. It was difficult to access public records of meetings or agendas based on information available on county and sheriff websites, making it even harder to review any decisions that may have been made during these meetings and to confirm if any members of the public were in attendance.

These findings coincide with concerns recently shared with the author by local community members and advocacy groups that have questioned the existence and use of steering committees and criticized ICE and local LEAs for restricting public access to such meetings. Community groups have shared stories of ICE and its local law enforcement partners changing, without advance notice, dates or locations of meetings and other practices. In Tennessee, for example, the advocacy group Allies of Knoxville’s Immigrant Neighbors noted that this “last minute meeting change” was made “to confuse the public and decrease the number of people who show up [to these meetings] to speak out against this [287(g)] program.”18 There have been complaints of ICE preventing community members from taping or video recording the meetings in jurisdictions that have open-meeting laws that support audio or video recordings of public meetings.19

Restricting public access seems to be a pervasive problem in a number of localities. On September 27, 2018, Salem County, New Jersey, hosted its annual 287(g) steering committee meeting20 at the ICE office in Newark, New Jersey. This location meant that in order for Salem County residents to attend to learn more about their 287(g) program or raise concerns with their local elected officials, they would have had to drive nearly two hours from home. Similarly, residents of other jurisdictions with steering committees have found that meetings are sometimes held at courthouses21 or ICE offices22 many miles away. Even more concerning, having meetings in courthouses or ICE offices may restrict access for community members who are immigrants, given the rise in ICE’s practice of targeting and arresting immigrants23 inside local courthouses.

Recommendations and conclusion

As the growth of 287(g) agreements is likely to continue nationwide, a lack of transparency and poor oversight will only aggravate their negative impacts24 on local communities. For localities, any attempts to discourage participation from community members, particularly those most affected by the 287(g) program, puts community trust at great risk and fails to provide the crucial oversight needed to prevent these programs from having adverse effects in communities.

The following recommendations provide a path forward to ensure that ICE and participating LEAs meet effective 287(g) program oversight:

- Every participating jurisdiction must establish a 287(g) steering committee that includes community stakeholders. Moreover, steering committees should hold regular meetings that are fully accessible to members of the public and that are announced accurately and in a timely manner.

- ICE should modify its template MOA to clearly require every participating jurisdiction to establish and utilize steering committees that meet regularly with external stakeholders. ICE should ensure that such steering committees are established and that meetings are taking place as required. In the same way that ICE now posts existing 287(g) contracts on its website, ICE can collect and provide advance public notice of all steering committee meetings to ensure that information is centralized and easily accessible to the public.

- Pursuant to congressional requirement included in appropriations report language, ICE must submit to Congress a report “not later than 60 days after the end of each fiscal year, including details on steering committee membership and activities for participating jurisdictions.”25

- Congress should conduct necessary oversight to ensure that ICE is fulfilling its duty to ensure that each participating jurisdiction has established and is regularly employing steering committees to meaningfully solicit input from local stakeholders. Congress should also withhold additional funding for the 287(g) program until oversight mechanisms are improved and requirements are met.

- The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) should have officials present at every steering committee meeting, consistent with the direction of Congress that the CRCL “continue providing rigorous oversight of the 287(g) program.”26

- Local community members should continue to pay close attention to the impacts of 287(g) programs in their communities, and they should demand transparency from their local government representatives by requesting that steering committee meetings, at minimum, occur annually.

The burden of immigration enforcement is negatively affecting not just immigrants but also communities nationwide. Under the Trump administration, 287(g) agreements are growing at an unprecedented pace and are becoming a key tool in the implementation of a mass deportation agenda. CAP’s research indicates that ICE and participating jurisdictions are ignoring an important opportunity to engage local stakeholders and ensure better oversight and transparency. It is imperative that localities considering deputizing their officers for immigration enforcement take the concerns noted in this issue brief seriously. The only way to improve public safety is by building and maintaining trust between police officers and the communities they serve.

Claudia Flores is the immigration campaign manager with the Immigration team at the Center for American Progress.

The author thanks Chris Rickerd from the American Civil Liberties Union and Tom Jawetz, Philip E. Wolgin, and Nicole Prchal Svajlenka from the Center for American Progress for providing research support and reviewing this brief.

* The draft committee report accompanying the FY 2019 House appropriations bill for the Department of Homeland Security,27 considered by the House Appropriations Committee, generally repeats this requirement, though the language is changed, perhaps inadvertently, to suggest that it is ICE—rather than the participating jurisdictions—that must hold regular steering committee meetings for each jurisdiction.