This brief contains a correction.

In the six years since the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program went into effect, its recipients, many of whom came to the United States as children, have lived through a roller coaster of policy shifts.1 Beginning with its implementation in 2012, DACA has provided eligible young people a temporary reprieve from deportation and has removed barriers to pursue opportunities and earn a living. Although it does not provide a permanent solution, DACA has given more than 800,0002 young people access to basic freedoms, including work permits, driver’s licenses, affordable higher education, and, in certain states, professional licenses.

Above all, DACA has relieved many individuals of the constant fear of being deported from the country they call home.3 Thousands of stories have emerged that depict how DACA has significantly changed recipients’ lives for the better. One such story from FWD.us details how DACA has allowed Chris to support his family in New York: He is “working, paying the bills, keeping the lights on … making sure everyone gets fed, that [his] family has a place to live.”4

Yet DACA recipients are currently living in limbo. After the Trump administration announced an end to DACA in September 2017 and started a clock on its phaseout, judges in three U.S. district courts—California, New York, and the District of Columbia—ordered the federal government to continue receiving and adjudicating DACA renewal applications, even as it would no longer consider new applications.5 In a separate lawsuit, Texas, along with seven other states, and two Republican governors from Mississippi and Maine challenged DACA, seeking to end the program.6 While Judge Andrew S. Hanen of the U.S. District Court in Texas decided not to issue a preliminary injunction in the states’ favor, he strongly hinted that he would likely find the program unlawful at a later date.7 As a result, although renewals continue to be processed, the fate of DACA is still up in the air.

What will happen if DACA ends

Losing DACA would have a profound impact on the program’s nearly 704,000 current recipients.8 DACA recipients are not eligible for most types of federal benefits, including Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act health insurance marketplace, and federal student aid, among others.9 But they have access to driver’s licenses in all states, in-state tuition and state-funded aid in some states, and occupational licenses in a few states. Depending on where they live, these recipients would be at grave risk of losing complete or partial access to these few provisions that have vastly improved their quality of life if DACA were terminated.

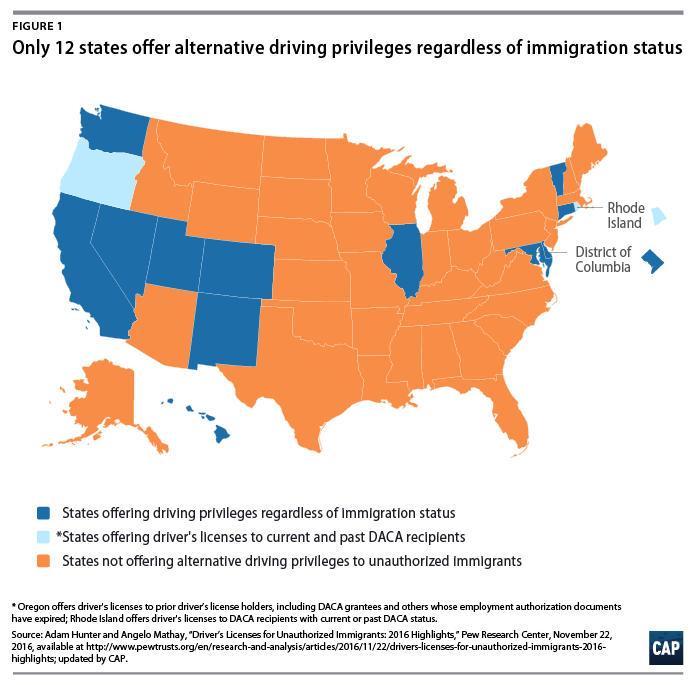

However, there are ways that states could help protect DACA recipients and provide some sense of normalcy in their daily lives should the program come to an end. A dozen states have already implemented common-sense solutions to ensure that their unauthorized immigrant residents can receive driver’s licenses. Students in many states have access to affordable higher education regardless of their immigration status. And a few states allow unauthorized immigrant professionals to obtain professional and occupational licenses. State policymakers can do more to provide DACA recipients access to these basic rights until Congress passes a permanent solution that includes a pathway to citizenship.

Recipients will lose access to driver’s licenses in a majority of states

Currently, DACA recipients have access to driver’s licenses in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico because under DACA, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has authorized them as lawfully present in the United States.10 A 2018 nationwide survey of DACA recipients showed that after receiving DACA, nearly 78 percent of recipients got their first driver’s license, and about 62 percent got their first state ID card.11

Access to a driver’s license can be life-changing for DACA recipients. Luis Gomez, who is pursuing his engineering apprenticeship, recalled in an interview with Time that getting his driver’s license was one of his most significant moments because it gave him the freedom to drive without fear of being pulled over.12 For others such as Giovanni, a DACA recipient interviewed in The New York Times, having a driver’s license meant being able to take a domestic flight.13 All of this may change, however, if DACA is terminated and current recipients are deemed as no longer lawfully present in the United States.

Only 12 states—California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Vermont, Washington—along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico extend driving privileges to all their residents, regardless of whether they have DACA.14 After the Trump administration’s September 2017 announcement rescinding DACA, Rhode Island and Oregon proactively enacted laws allowing DACA recipients to keep their driver’s licenses, provided they meet certain conditions.15 This means that DACA recipients in 14 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico will still have access to an alternative card that allows them to drive legally. Importantly, however, the alternative driver’s licenses these states issue are limited in use and must appear different from a federally recognized driver’s license pursuant to the terms of the REAL ID Act.16 And because the cards are not federally recognized, beginning in October 2020, they cannot be used by individuals who wish to board a commercial airplane.17

The majority of, or nearly 377,000, DACA recipients live in 36 states where they will lose their driver’s licenses when or shortly after their DACA expires.18 Unless they live in an area that offers a municipal ID card, such as New York City, they will also lose an official ID card with which to identify themselves. Without a proper ID, it will be difficult for them to open a bank account, pick up a prescription, cash a check, or rent an apartment. According to Public Radio International, the immediate fear for Jasiel López, a DACA recipient in Florida, is having to drive to school without a valid license.19

Higher education will be less accessible

According to CAP’s 2018 DACA survey, nearly 40 percent of respondents in a national survey are enrolled in secondary or postsecondary education, with more than 74 percent of them pursuing a bachelor’s degree or higher.20 DACA has provided opportunities for recipients such as Yanet in Arizona, who according to the National Immigration Law Center has been able to enroll in college and study to become a nursing assistant.21 While it is expensive for her to continue taking classes, Yanet is working multiple jobs to make ends meet and aspires to become a registered nurse in a state that will soon have the greatest nursing shortage in the country.22 Her dream may be cut short if DACA ends.

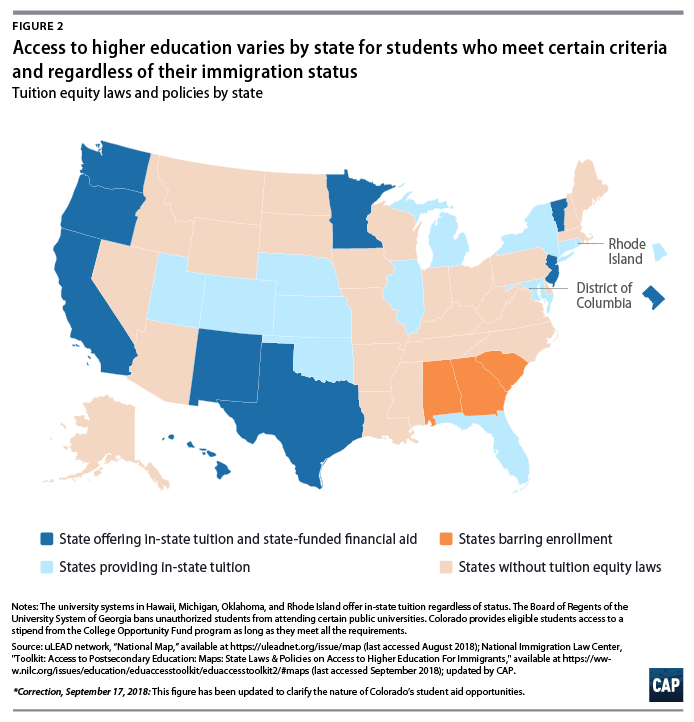

Tuition equity policies are highly variable across states, and the impact of ending DACA will likely differ even among colleges and universities within the same state. For example, DACA students’ ability to pay in-state tuition will be disrupted at public colleges and universities in at least three states: Virginia, Massachusetts, and Ohio.23 Students among the nearly 20,600 people with DACA in these states are at risk of losing their access to public colleges and universities because of the prohibitive difference between in-state and out-of-state tuition.24 At Virginia Commonwealth University, for example, out-of-state tuition costs $35,798 per year—$20,000 more than in-state tuition and fees.25 In February 2017, Angel Cabrera, president of Virginia’s George Mason University, said that, if DACA expires, anywhere between 150 and 300 students may have to drop out of the university due to unaffordable tuition.26

States without tuition equity laws or policies may deny unauthorized immigrants in-state tuition. At least seven states—Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, and South Carolina—have laws that expressly deny in-state tuition to unauthorized immigrant students.27 But some of these states, including Arizona, Missouri, and Georgia, also deny DACA recipients access to in-state tuition, so ending DACA will not affect the status quo.28

Furthermore, in select states, DACA recipients stand to lose not just their access to in-state tuition, but also their ability to access higher education altogether. States such as Alabama and South Carolina bar unauthorized immigrants from enrolling in their public institutions. Select universities in Georgia also deny enrollment.29 If DACA is terminated, students among the 32,000 active DACA recipients in these three states will not be able to enroll or continue their education in the affected public institutions.30

The District of Columbia and at least 20 states or their university systems offer in-state tuition to students regardless of their immigration status, provided they meet certain criteria.31 Around 76 percent of active DACA recipients reside in these states and will generally not be affected should they choose to pursue higher education.32 A handful of states among these, such as California, Texas, and New Jersey, also provide access to state-funded aid to students regardless of their immigration status, provided they meet certain criteria.

Access to professional and occupational licenses will be further limited

Many professionals in the United States, including landscapers, manicurists, barbers, and more are required to hold a license to practice in their industry. State licensing boards generally regulate these licenses, but under federal law, certain immigrants, including unauthorized immigrants, are ineligible to receive professional licenses unless states enact a law that affirmatively provides them eligibility.33

After DACA, several states extended some or all professional licenses to people who have work authorization, including DACA recipients. Most states granting such licenses follow a simple logic: They want professionals trained in their field to be able to contribute fully to the state economy. In 2015, Nevada allowed the superintendent of public instruction to issue teaching licenses to individuals who have work authorization.34 Signed into law by Gov. Brian Sandoval (R-NV), this bill helped DACA recipients such as Uriel Garcia, who was studying to become an elementary school teacher but was previously unable to complete his practicum at Nevada State College because it required a teaching license.35

In 2016, Nebraska lawmakers overrode the governor’s veto to provide work-authorized immigrants access to professional and occupational licenses for more than 170 occupations, including a law license.36 In reference to DACA recipients, Judiciary Committee Chairperson Sen. Les Seiler (R-NE) of Hastings, Nebraska, who supported the bill, stated, “We raise them, we educate them and then we tell them to go across the river and practice in Iowa. That should never happen.”37 According to KETV Omaha, for Nebraskans such as Brenda Esqueda—who aspired to be a teacher in Omaha—the bill meant that she could finally realize her dream.38

Also in 2016, the New York Board of Regents authorized DACA recipients to access more than 57 professional licenses and certain teacher certifications.39 Most recently, in February 2018, Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb (R) and the Republican-led state legislature prioritized DACA recipients’ access to professional licenses after the Indiana Professional Licensing Agency concluded that recipients could not be issued licenses under a previously enacted law.40 Within weeks of that determination, Gov. Holcomb signed the bill into law, allowing DACA recipients to earn professional licenses in more than 70 occupations.41

Furthermore, states such as Florida and Illinois have laws that expressly allow DACA recipients access to law licenses provided they meet certain conditions.42 In New York, the appellate court issued an opinion that Cesar Vargas, a DACA recipient, could be admitted to the state bar, indicating that federal law restricting issuance of professional licenses by states “unconstitutionally infringes on the sovereign authority of the state to divide power among its three coequal branches of government.”43 For Cesar and many others like him, getting a law license means that they can pursue their dreams to fight for justice.44

Among all respondents to the 2018 survey of DACA recipients, more than 90 percent are working and contributing to their state’s economy.45 According to the American Civil Liberties Union, Marina Di Stefano, who is a doctor in Philadelphia, will not be able to practice medicine and provide service to underserved people even though she spent years training to do so.46 There are nearly 100 DACA recipients currently enrolled in medical schools across the nation.47 DACA recipients in a profession that requires a license and who live in a state that would not extend that license to unauthorized workers will be negatively impacted. At this point, California48 and, most recently, Illinois49 are the only states that issue professional licenses to individuals regardless of their immigration status—making them trailblazers on this issue.

States should act now to protect DACA recipients

In the face of congressional inaction to secure a permanent solution for DACA recipients and the United States’ larger population of Dreamers, states have the power to ameliorate some of the damage that will be done if the Trump administration is successful in ending DACA. For example, the states that have not yet done so can pass common-sense measures such as issuing driver’s licenses to individuals regardless of immigration status. Indeed, this would be beneficial for both individuals and states, as it would lead to improved road safety by allowing people to get licensed and increased revenue through vehicle taxes and other fees.50 Making higher education affordable through in-state tuition and state-funded financial aid for individuals, regardless of immigration status, who want to pursue their education will ensure that the talent stays in their state. Furthermore, all states should ensure that individuals are able to get licensed in their chosen professional or occupational field.

Although the burden is on Congress to pass legislation that provides Dreamers a pathway to citizenship, states can take action in the meantime to protect them and help ensure that once Congress does its job, these young people will have everything they need to realize their full potential. These issues do not represent the full universe of actions that states can take—but they do provide a place for states to begin protecting the basic rights of a group of people who call America home.

Silva Mathema is a senior policy analyst for Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress.

The author is grateful to Tanya Broder from the National Immigration Law Center and Greg Siskind from Siskind Susser PC for their valuable insights and to Tom Jawetz and Philip E. Wolgin from the Center for American Progress for reviewing this issue brief.