This issue brief contains a correction.

“We many thousands of past and present proud immigrants to this great country did not have the choice of choosing our place of birth or choice of parents. We did have the choice to be called immigrants by birth and Americans by choice. We were always Americans in our hearts.”

— Alfred Rascon, a native of Mexico, winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor, and former director of the Selective Service

In the wake of the Senate’s passage of the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act, S. 744, in June by a bipartisan supermajority of 68 to 32, the drumbeat for immigration reform has only increased. Over the past few weeks, House Democrats introduced a version of the Senate bill in H.R. 15, and a growing chorus of bipartisan voices has pushed for reform that would put most of the 11.7 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States on a path to citizenship. Nevertheless, the House has so far failed to bring any immigration bill to the floor. While much of the immigration debate in Congress has revolved around issues of border security and even the economic contributions of immigrants, far less has been discussed about the contributions that immigrants make in other areas, particularly through their military service.

Immigrants and their children comprised half of the total U.S. population growth between 1990 and 2010, and one-quarter of all children under age 18 living in the United States have at least one immigrant parent. Immigrants and their children are increasingly vital resources to military recruitment, serving as soldiers, marines, sailors, and airmen. The active-duty military currently contains more than 65,000 immigrants—5 percent of the force—and noncitizen immigrants account for 4 percent of all first-term military recruits. Roughly 3 percent of all living U.S. veterans were born abroad, and 12 percent of all living veterans are either immigrants or the children of immigrants.

Immigrants serving in the military bring special skills, including language and cultural competencies; are less likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to leave the military before completing a tour of duty; and have historically served with distinction—20 percent of all Medal of Honor recipients were born abroad.

In light of Veterans Day, this issue brief looks at how immigrants have historically played—and continue to play—a key role in U.S. military readiness.

A brief history of immigrant service members

Immigrants have served in and fought for the U.S. military since the birth of the nation—from the Revolutionary War to the present. For example, immigrants—mostly Irish and German—comprised 18 percent of the Union Army during the Civil War. During World War I, more than 192,000 immigrants acquired citizenship through military service, accounting for more than half of all naturalizations in the United States during that period.

Military service has historically been regarded as a tool for socializing immigrants to the American culture and way of life. Early 20th-century political leaders upheld the U.S. military as a “school for the nation,” particularly for the multitude of new immigrant arrivals. Henry Breckinridge, who served as the U.S. assistant secretary of war from 1913 to 1916, noted the power of individuals from various creeds and countries “all rubbing elbows in a common service to a common Fatherland.”

Historians, too, argue that the U.S. military institution has played an important role in reshaping American society and integrating diverse racial and ethnic groups into the American polity. During World War I, military policies encouraged immigrant soldiers to forge new identities as Americans while maintaining their ethnic pride and values. African Americans and whites worked and lived together after World War II in a pre-civil rights era desegregated military. From 1907 to 2010, well over half a million immigrants—more than 710,000 individuals—naturalized through military service, accounting for 2.5 percent of all naturalizations during this period.

By the numbers: Military service of immigrants today

The most recent data available from the Department of Defense, or DOD, show that the active-duty military is comprised of more than 65,000 immigrants, or 5 percent of the active-duty force; this group includes both naturalized U.S. citizens and noncitizens. Immigrant service members come from nations across the globe, but the top five countries of origin are concentrated in Asia and Latin America. Among current immigrant service members:

- 22.8 percent are from the Philippines

- 9.5 percent are from Mexico

- 4.7 percent are from Jamaica

- 3.1 percent are from Korea

- 2.5 percent are from the Dominican Republic

More recently, the DOD reported that 24,000 noncitizen immigrants served in the U.S. military in 2012, with 5,000 legal permanent residents—green card holders—enlisting each year.

Immigrant veterans

In 2012, 608,000 veterans, or 3 percent of the living U.S. military veteran population in the United States, were foreign-born. As with current service members, Filipino (11.8 percent), Mexican (7 percent), and Jamaican (3.1 percent) immigrants are featured prominently among the veteran population.

Contributions of U.S.-born children of immigrants

Immigrants and their children comprised half of the total U.S. population growth between 1990 and 2010, and one-quarter of all children under age 18 living in the United States have at least one immigrant parent. Children of immigrants are increasingly vital resources to military recruitment, and scores of U.S.-born children of immigrants have served as soldiers, marines, sailors, and airmen.

No information is available on the number of current service members who are U.S.-born children of immigrants, because the Department of Defense does not maintain information on the countries of origin of the parents of service members. However, 9 percent of all living military veterans are U.S.-born children with at least one immigrant parent. Famous veterans who are U.S.-born children of immigrants include: Colin Powell, retired four-star general in the U.S. Army and former secretary of state; and Leon Panetta, current secretary of defense, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and former Army intelligence officer. Combined, veterans who are immigrants or children of immigrants account for 12 percent of the total veteran population.

The DREAM Act

By Philip E. Wolgin

The Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, or DREAM Act, is an important piece of legislation that would provide a road map to citizenship for young undocumented Americans, allowing those who want to serve their country in the armed forces to do so. Each year since Sens. Richard Durbin (D-IL) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT) first proposed it in 2001, the DREAM Act has been introduced in Congress. Although the exact requirements have changed over time, in general, the DREAM Act allows people who entered the United States prior to age 16, have lived in the United States for a significant period of time, and have completed high school and some college or military service to be put on a path to citizenship. In 2010, the DREAM Act failed in Congress, after passing the House of Representatives but falling five votes short of overcoming a filibuster in the Senate.

In the meantime, undocumented Americans who want to serve in the armed forces have so far been blocked from doing so under the military’s current policy. And while the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program—announced by President Barack Obama in June 2012—allows many DREAMers to apply for a two-year reprieve from deportation and a work permit, it does not confer a specific legal status. As a result, up to this point, recipients of DACA have been deemed ineligible to serve.*

Passing the DREAM Act would provide a significant boost to our economy, adding $329 billion to the U.S. economy over the next two decades. In 2010, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates wrote to Congress in support of passing the DREAM Act, stating that the legislation “will result in improved recruitment results and attendant gains in unit manning and military performance.” Other military leaders, such as David S.C. Chu, the undersecretary of defense for personnel and readiness under President George W. Bush, have made similar statements, with Chu writing that “many of these young people may wish to join the military, and have the attributes needed—education, aptitude, fitness, and moral qualifications.” Passage of the DREAM Act, or its inclusion in a comprehensive immigration reform package—such as the one included in the Senate-passed immigration reform bill, S. 744, in June of this year—would go a long way to improving military readiness.

Cesár Vargas is one of the DREAMers who wants to serve his country. Even though Vargas graduated from college and law school and aspires to serve in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, his lack of papers keeps him from serving his country. Nevertheless, Vargas has been at the forefront of advocacy around the DREAM Act, immigration reform, and allowing DREAMers to serve in the military. He is the executive political director of the DRM Action Coalition, a group dedicated to lobbying on behalf of the DREAMer movement. He also helped found the website letusserve.org to collect stories of other DREAMers like himself, who aspire to serve.

Immigrants are a critical part of U.S. military preparedness

The Department of Defense has taken special notice of immigrants and their potential to meet U.S. military personnel needs while also helping to maintain high-quality force standards. In 2010, the DOD unveiled its support for the DREAM Act (see text box), integrating it into their 2010-2012 strategic plan to aid in military recruitment. That same year, the DOD also highlighted the noncitizen immigrant population in their annual “Population Representation in the Military Services” report. Their report outlined noncitizen population size and eligibility-to-serve criteria, such as being a legal permanent resident, having a high school degree, and English proficiency. Aside from the sheer number of people that would qualify—1.2 million noncitizens in the prime recruiting ages of 18 to 29 that meet this criteria—DOD recognizes that noncitizens also possess skills that are pivotal to future military strategy and military success.

Unique skills

The U.S. military environment shifted greatly after 9/11, with the prolonged involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq, and greater cooperation with allies in the region. The dearth of military and civilian leadership possessing language and cultural competencies appropriate to these regions created a vacuum that hampered military success and critical on-the-ground coalition-building capacity.

Recognizing the unique and essential linguistic and cultural diversity of immigrants born and socialized in cultures of strategic military interest, policymakers and military leaders actively sought to engage immigrants from these and other regions projected to be of national interest now and in the future. Secretary Panetta, in an August 10, 2011, memo on “Language Skills, Regional Expertise, and Cultural Capabilities in the Department of Defense (DoD),” underscored the importance of these skills:

Language, regional and cultural skills … are critical to mission readiness in today’s dynamic global environment. Our forces must have the ability to effectively communicate with and understand the cultures of coalition forces, international partners, and local populations.

Lower attrition

Not only do immigrant service members contribute to linguistic and cultural capabilities, but noncitizens are less likely than U.S. citizens to drop out of military service. Leaving the military before completing a tour of duty, also known as attrition, is a historical and costly problem for the armed forces. Recruiting, training, transporting, clothing, feeding, and paying enlistees is expensive, so each time an individual drops out of service, he or she must be replaced at additional expense. Noncitizens are less likely to drop out than U.S. citizens at each standardly measured point in time—after 3 months, 36 months, or 48 months of service.

Noncitizens consistently maintain approximately half the dropout level as U.S. citizens. After three months of service, for example, only 4 percent of noncitizen recruits versus 8.2 percent of U.S. citizens have dropped out of service; at 48 months, 18.2 percent of noncitizens versus 31.9 percent of U.S. citizens have dropped out. Lower attrition rates translate into cost savings for the military. And because noncitizens account for 4 percent of all first-term recruits across military branches, these cost savings are significant.

Outstanding service

Immigrant service members also perform well on the battlefield. The Congressional Medal of Honor award is the highest military decoration bestowed upon a living or deceased service member, and 20 percent of all award recipients have been immigrant service members. The courageous—and often fatal—actions to assist fellow service members in the face of grave danger demonstrate the great lengths that immigrant service members will go to uphold their military duties and serve the United States.

Take the story of Navy Cross awardee Marine Sergeant Rafael Peralta. Born in Mexico, Peralta enlisted in the U.S. armed forces after becoming a legal permanent resident. On November 15, 2004, Peralta, a 25-year-old platoon scout serving in Fallujah, Iraq, was shot during a firefight during a house search and fell to the ground, wounded. When his fellow marines entered the room where he lay, the suspected terrorists threw a grenade close to Peralta. Peralta grabbed the grenade and pressed it to his body, absorbing its deadly blast, and saving the lives of six fellow marines. In a letter to his 14-year-old brother before his death, Peralta clearly expressed his motivations for serving and his love for his adopted country: “I’m proud to be a Marine, a U.S. Marine, and to defend and protect the freedom and Constitution of America. You should be proud of being an American citizen.”

Expedited naturalization and special programs

Expedited citizenship

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 endows the president with the authority to expedite citizenship for immigrant U.S. military service members. Although green card holders must wait five years before they can apply for naturalization, those who enlist in the armed forces are eligible to apply for expedited citizenship. During peaceful periods unmarked by hostilities, noncitizen service members must wait only three years to be eligible to apply for citizenship. During periods of armed conflict, they are eligible to apply for citizenship after much shorter periods of time. In 2002, for example, President Bush signed an executive order declaring that noncitizens who served in the military since September 11, 2001, were eligible to apply for citizenship after only one day of active-duty service.

During the post-9/11 period, the U.S. military instituted programs targeted at recruiting immigrants, but these service members frequently experienced roadblocks and delays when they applied for citizenship. Immigrant service members who engaged in overseas missions to protect U.S. interests were prohibited from becoming U.S. citizens—even if all requirements were met—because they could not fulfill the naturalization requisite to be physically present in the United States to complete the process.

In 2004, the government lifted the residence and physical presence restrictions, allowing thousands of immigrant service members to apply and receive citizenship while serving in Iraq, Afghanistan, Germany, Korea, and other foreign countries. Application fees were eliminated and every military installation was required to appoint a designated point of contact to help noncitizen service members complete and file naturalization paperwork, further removing obstacles in obtaining U.S. citizenship.

Between 2009 and 2013, all military service branches, with the exception of the Coast Guard, have further facilitated the citizenship process by working with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS, to establish the “Naturalization at Basic Training Initiative.” This initiative allows noncitizen enlistees to be naturalized when they graduate from boot camp if they meet requisite criteria, which include possession of good moral character, English language knowledge, knowledge of U.S. government and history, and an Oath of Allegiance to the U.S. Constitution. All aspects of the naturalization process, including capturing biometrics, the naturalization interview, and administration of the Oath of Allegiance, are conducted by the USCIS on the military base.

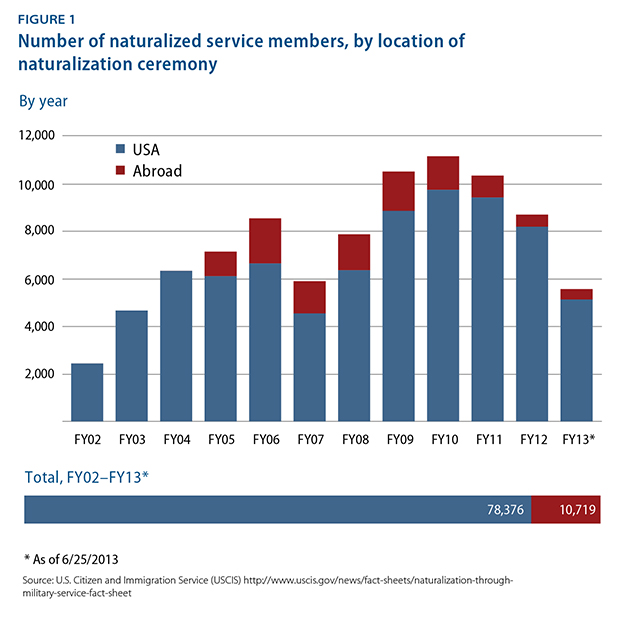

Overall, these initiatives have proven successful and popular among service members. Between September 2002 and June 2013, 89,095 noncitizen members of the U.S. armed forces became U.S. citizens, with 10,719 of these naturalizations occurring at USCIS naturalization ceremonies in 28 countries, including Afghanistan, Djibouti, El Salvador, Haiti, Iraq, Kenya, Mexico, the Philippines, and South Korea.

In addition, noncitizen service members who served honorably during periods of hostility, and who died because of injury or disease resulting from their military service, are eligible to receive posthumous citizenship if their next-of-kin apply within a designated timeframe. USCIS data show that posthumous citizenship was awarded to 138 noncitizens between 2001 and 2012.

Special programs targeting immigrants and native language speakers

09L

Because of the severe shortage of U.S. military linguists in dialects common to Iraq and Afghanistan, and the pressing need for them after 9/11, the Army launched the 09L program in February 2003 to recruit and train linguists and interpreters. Program planners observed that training linguists to be soldiers was more cost effective, faster, and efficient than turning soldiers into linguists. Seasoned linguists possess skills that take years to cultivate, while basic training to become a soldier only requires a matter of weeks. The original 09L program targeted Arabic, Dari, and Pashto speakers, and immigrants have been crucial to the program’s success: Two-thirds of original program recruits were legal permanent residents while one-third were U.S.-born.

Military Accessions Vital to National Interest

Because of the military’s difficulty in recruiting individuals with necessary skills for military readiness, the Department of Defense piloted the Military Accessions Vital to National Interest, or MAVNI, program in 2009 to allow immigrants who are legally present—such as those on temporary visas, or those with Temporary Protected Status—but not permanent residents to enlist. (Undocumented immigrants are ineligible under MAVNI.)

Initially, the program was limited to recruiting 1,000 individuals with special skills—such as physicians, nurses, and individuals with special language or cultural skills—890 for the Army, 100 for the Navy, and 10 for the Air Force. The MAVNI program quickly met its quotas and was deemed such a success that it is currently being re-piloted between 2012 and 2014, with a raised recruitment cap of 1,500 individuals a year.

Conclusion

With ongoing missions and continued and growing strategic interests in the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Africa, recruiting and training military personnel with non-Western linguistic and cultural capabilities is pivotal to future U.S. military missions. As these capabilities are often rare or unavailable among U.S.-born citizens, immigrant service members and children of immigrants with language and cultural competencies have proven to be critical to filling this gap.

The military must recruit the best and brightest individuals that it can attract. By tapping into the pool of immigrants and children of immigrants—something that would only be amplified by passing immigration reform and allowing all those who wish to serve the ability to do so—the U.S. military ensures that it will continue to do just that.

Catherine N. Barry, Ph.D., is a research consultant and program evaluator for government, nonprofit, and for-profit organizations. Her dissertation, “Moving On Up? U.S. Military Service, Education and Labor Market Mobility among Children of Immigrants,” examines the motivations behind military enlistment and post-military educational attainment and employment among foreign- and U.S.-born children of immigrants.

*Correction, November 13, 2013: This issue brief originally stated that individuals who are not legally present in the United States are ineligible to serve in the armed forces. The brief has been modified to reflect that this legal conclusion is disputed and that it is only the DOD’s current policy.