As we move into the congressional debate on immigration reform, we should remember that the political shifts that have opened a space for reform—grounded in demographic changes—were not a phenomenon that debuted in 2012. These changes began in the mid-1990s, when anti-immigrant politics in California helped turn the state reliably blue.

And as our nation moves toward a point where by 2043 we will have no clear racial or ethnic majority,11 other states such as Arizona, Texas, North Carolina, and even Georgia are also reaching demographic tipping points. Whether or not these states turn blue in the future has a lot to do with how politicians in both parties act and what they talk about on the subject of immigration reform.

In this issue brief we review the past, present, and future of immigration politics, as well as the changing demographics in key states.

Demography is destiny

- The past: California

- The present: Florida, Colorado, Nevada, and Virginia

- The future, near term: Arizona, North Carolina

- The future, long term: Georgia, Texas

The past

California

In 1994 California’s Proposition 187 awakened the Latino vote and pushed the state into the reliably Democratic column. Then-Gov. Pete Wilson (R) strongly supported the ballot measure, which targeted unauthorized immigrants in the state, attempting to cut off all public services outside of emergency health care to people without legal status. Proposition 187 passed overwhelmingly by a margin of 59 percent to 41 percent, though the courts ultimately struck it down as unconstitutional. The backlash to the ballot measure and the governor’s support of it was swift, however, galvanizing Latinos to go to the polls. In fact, not a single Republican won statewide office from the passage of Proposition 187 in 1994 through the election of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (R) in 2003, and the state has voted Democratic in every presidential election since 1992.

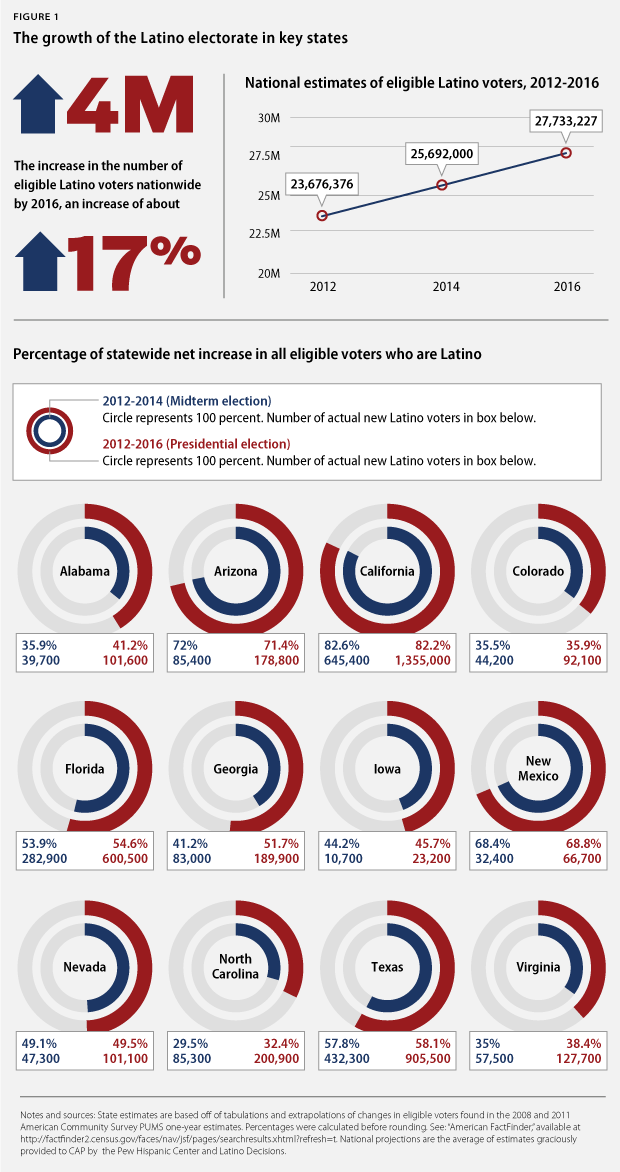

Proposition 187 energized the Latino vote, and demographic realities since then have only accelerated the state’s political changes. From 1990 through 2010 California’s Latino population grew from 25 percent to 38 percent, while the state’s Asian American population grew from 9 percent to 13 percent. California reached majority-minority status—meaning the state has no one racial or ethnic majority—in 2000, decades before the country as a whole is projected to do the same. The Latino voting-eligible population in the Golden State will continue to grow, as a large number of Latinos turn 18 and become eligible to vote. By 2016 California will have 1.35 million new Latino voters, accounting for 82 percent of the state’s growth in eligible voters.

California represents a powerful example of the role that immigration and demographics plays in partisan politics, and it was an antecedent to the 2012 presidential election, where states such as Florida, Colorado, and Nevada moved into the reliably Democratic column.

The present

Florida

Republicans lost their political monopoly in Florida in the 2008 presidential election, when the state went Democratic for the first time since 1996. Major growth in communities of color, which made up 30 percent of the state’s electorate in 2008 and was driven largely by growth in the Hispanic population, played a significant role in President Obama’s election. Four years later in 2012, President Obama carried the Latino vote in Florida with 60 percent to Gov. Romney’s 39 percent, up 3 percentage points from his voter margin in the 2008 election.

Unique to Florida’s Latino electorate is the fact that Cuban Americans, who tend to lean Republican, make up the largest portion of the state’s Latino electorate—32 percent—while Latinos of Puerto Rican origin make up 28 percent of the state’s Latino eligible voters. Immigration is not as critical an issue for either of these communities as it is for other groups, since Cuban Americans benefit from generous immigration policies that grant them legal status once they’ve arrived in the United States, and Puerto Ricans are already U.S. citizens.

Even so, polling illustrates that these groups rejected heated political rhetoric on immigration, especially that which painted a target on the backs on all Latinos. An ImpreMedia and Latino Decisions election eve poll in Florida asked Cuban American and Puerto Rican voters how Gov. Romney’s outreach to the Latino community had communicated his feeling toward them. Only 37 percent of voting-eligible Cuban Americans and 16 percent of Puerto Ricans said they believed Gov. Romney truly cared about Latinos. Polling among Mexican, Dominican, and other Latino communities in the state was similarly abysmal.

The perception of Republican Party hostility toward Latinos became crystal clear at the ballot box. President Obama won the Puerto Rican vote by wide margins—83 percent to Gov. Romney’s 17 percent—and while the president narrowly lost the Cuban American vote—48 percent to Gov. Romney’s 52 percent—he won a greater proportion of this vote than any previous Democratic candidate has in the state. What’s more, President Obama won 60 percent of Cuban American voters born in the United States, illustrating the potential for greater gains as the foreign-born Cuban American population ages. Similarly, as a large number of Latinos come of age and become eligible to vote, the political influence of Latinos in Florida will only increase. By 2016 there will be an additional 600,500 eligible Latino voters, making Latinos account for nearly 20 percent of the state’s voting-eligible electorate.

Colorado

The battleground state of Colorado stayed blue in 2012, as it was in 2008, primarily due to high turnout by Latino voters, who supported President Obama over Gov. Romney by a margin of 87 percent to 10 percent. These voters comprised 14 percent of all voters in the state, up 1 percent from 2008. With 86 percent of Latinos telling pollsters that Gov. Romney did not care about or was hostile to Latinos, it should be no surprise that the president performed as strongly as he did with Colorado’s burgeoning Latino voter population. The 2012 election results followed those of 2010, when Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) eked out a victory over Tea Party candidate Ken Buck with a margin of just more than 1 percent, but with 81 percent of the Latino vote supporting him.

Sweeping demographic changes are helping move Colorado from a swing state to a reliably Democratic state. But these political shifts did not come out of nowhere. As in California in the mid-1990s, restrictive state-level anti-immigrant policies, particularly those championed by former Colorado State Rep. and later U.S. Congressman Tom Tancredo (R), awakened the state’s Latino vote. In 2006 the Colorado General Assembly passed S.B. 90, which required local law enforcement officers and agencies to report anyone arrested for a criminal offense and suspected to be in the country without legal status to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In the majority of cases, those taken into custody after S.B. 90 was implemented have been charged with minor offenses, in spite of the bill’s language requiring police to report only those who have been arrested for violent acts.

In a state where 63 percent of Latinos say they know an undocumented immigrant, it is not hard to see why extremist rhetoric and legislation on immigration increased Latino voter turnout, which rose 23 percent between 2000 and 2008. And as the results of the 2012 election demonstrate, the Latino vote in the state is only gaining steam. By 2016 Latinos will make up nearly 16 percent of the Colorado electorate and have 92,100 more eligible voters than in 2012. This reality will likely put the state squarely in the blue column for years to come.

Nevada

In addition to Colorado, Nevada is another swing state that is quickly moving into the reliably blue column. The Latino population in Nevada has grown considerably in the past decade, rising to 26.5 percent today from 19.7 percent in 2000. Latinos comprised 46 percent of the state’s overall population growth in the past decade and will account for 50 percent of the growth in the state’s electorate between 2012 and 2016. Latinos in Nevada, who make up 18 percent of the state’s eligible voting population and will account for 20 percent by 2016, voted for President Obama in 2012 in even greater proportions—80 percent—than in the entire nation.

The power of the Latino vote to sway elections was clearly evident in Nevada’s 2010 senatorial election. Even though pundits predicted a resounding loss for Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV), he won re-election, largely riding the wave of an impressive 90 percent of the Latino vote. His opponent, Republican Sharron Angle, attempted to use immigration as a wedge issue and paid the price. She claimed Sen. Reid was too soft on unauthorized immigration, even going as far as releasing a series of racially charged ads that featured ominous portrayals of undocumented immigrants crossing the border, one with an assault rifle at hand.

In the 2012 election, even the Romney campaign’s efforts to send Gov. Romney’s Spanish-speaking son Craig and Sen. Rubio to campaign on his behalf in the state could not tip the scales for him in Nevada. In fact, as election season progressed, and as Nevada’s Latinos learned more about the Romney immigration plan, support for President Obama increased—from 69 percent in June 2012 to 78 percent in September 2012—while support for Gov. Romney decreased—from 20 percent to 17 percent over the same time period. That’s partly due to the fact that 67 percent of Nevada’s Latino voters say they know someone who is undocumented, and 54 percent say they know a young person who would qualify for the DREAM Act. For them, immigration is a personal issue, and Gov. Romney’s tough line on immigration, as well as his position on vetoing the DREAM Act, hurt his support. With 80 percent of the state’s Latinos voting Democratic, the message from 2010 and 2012 is clear: As long as Republican candidates continue to adopt self-defeating immigration policies, they cannot hold the state.

Virginia

Virginia is the final state currently shifting Democratic—a change that is being propelled in part by the state’s growing Latino community. The Latino population in the state has increased 92 percent since 2000, reaching 8.2 percent of the total Virginia population in 2012. And although the Latino share of all voters in Virginia held steady from 2008 to 2012 at 5 percent, the razor-thin margin of the presidential and Senate races this past election cycle made their vote that much more decisive. By 2016 we can expect the Virginia electorate to see more than 127,700 new eligible Latino voters.

As in states such as Colorado, the candidates’ positions on immigration mattered in Virginia in 2012. Gov. Romney’s bedrock belief that undocumented immigrants should self-deport was not new to Virginia and echoed debates that occurred in 2007. That year the Prince William County Board of Supervisors implemented a measure that required law enforcement to obtain proof of legal status for any person arrested whom the officer had probable cause to believe was in the country illegally. The measure caused deep distrust between the Latino community and the police in the county, and cost Prince William County dearly when many of its Latino residents moved their families and their business to neighboring counties.

In polling completed one month before the November 2012 elections, 66 percent of Latino voters in Virginia supported President Obama, while only 22 percent supported Gov. Romney. These figures were up sharply from June 2012, when 59 percent of Latinos supported the president and 28 percent supported the governor. According to the polling firm Latino Decisions, much of the difference came from the Obama administration’s announcement of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, and from the Romney campaign’s extreme self-deportation rhetoric. As in other states, half of Virginia’s Latino voters told pollsters that they knew someone who was undocumented, making the immigration issue deeply personal for them. Unsurprisingly, then, 66 percent of Virginia’s Latinos voted for President Obama while only 31 percent voted for Gov. Romney. Similar to Florida, Colorado, and Nevada, without a shift in immigration rhetoric from the Republican Party, Virginia will remain reliably blue going forward.

The future: Near term

Arizona

Among the states that President Obama lost in both 2008 and 2012, Arizona is the most primed to benefit from these demographic shifts and switch from reliably Republican to a swing state and ultimately even to reliably Democratic. In both the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, the Republican candidate won 54 percent of the vote in Arizona, while the Democratic candidate won 44 percent and 45 percent of the state’s vote in 2008 and 2012, respectively. Yet, as Latino Decisions wrote in October 2012, Latinos in the state were far more enthusiastic about voting in 2012—more than the general electorate but also far more than in 2008. In total, 79 percent of Latino voters in the state voted for President Obama, and only 20 percent voted for Gov. Romney.

Latinos in Arizona already comprise 30 percent of the state population, and the explosive growth of the state’s Latino population—rising 46 percent in a decade—contributed to the state gaining an extra congressional seat after the 2010 Census. As CAP Senior Fellow Ruy Teixeira pointed out in May 2012, the 2012 electorate in Arizona was on track to see 3 percent to 4 percent more minority voters than in 2008, and 3 percent to 4 percent fewer white working-class voters. By all counts, Latinos are making up increasingly larger shares of the Arizona voting bloc. By 2016 we estimate that Latinos will make up about 25 percent of the state’s eligible voters, up from 22 percent in 2012.

These demographic changes have been on a collision course with the state’s harsh anti-immigrant policies. Arizona is no stranger to state-level attempts to push attrition through enforcement policies, attempting to make life as difficult as possible for undocumented immigrants so that they “self-deport.” In 2007 the state mandated the use among all employers of the Internet-based employment verification system E-Verify—which makes it harder for unauthorized immigrants to work in the state, while giving them no way to become legal—with the Legal Arizona Workers Act. And in 2010 the state passed S.B. 1070, a comprehensive anti-immigrant bill that made it a state crime to be without status or to work without status in Arizona, and allowed the police to ask for proof of status from anyone they suspect to be unauthorized. Although the Supreme Court struck down most of S.B. 1070 in June 2012, Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer (R) continues to push anti-immigrant policies, most recently denying driver’s licenses to recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status.

These anti-immigrant policies, particularly S.B. 1070, have radically reshaped the political landscape in Arizona. While Latino voters in the state already favored Democratic presidential candidates in 2004 and 2008, they sharply broke with the Republican Party after 2010. In fact, the Democratic share of the Latino vote rose from only 56 percent in 2008 to a full 81 percent in 2012. And in the interim between the presidential elections, Arizona State Sen. Russell Pearce (R), the architect of S.B. 1070, became the first-ever Arizona state senator to be recalled in 2011, largely on the strength of Latino voters. Polling on the eve of the Supreme Court decision illustrated that S.B. 1070 was deeply unpopular with the state’s Latinos, 79 percent of whom believed that even legally present Latinos would be the victims of racial profiling under the law. That same off-year election saw underdog Democratic candidate Daniel Valenzuela harness the Latino vote to defeat the Republican favorite Brenda Sperduti by a 56 percent to 44 percent margin in a Phoenix City Council race.

Adding fuel to the fire, Gov. Romney stated in a February 2012 presidential debate that Arizona’s E-Verify law should be a “model” for the nation, and he actively promoted the self-deportation policies at the heart of S.B. 1070. All of these policies led to Latino voters’ overwhelming rejection of the Republican Party in 2012. In the end, although Arizona ultimately remained in Republican hands in 2012, as Ruy Teixeira and John Halpin pointed out, “The extraordinarily rapid rate of demographic change in the state”—and, we would argue, the shift in Latinos’ political identity brought about by Arizona’s anti-immigrant legislation—“will likely put it in play in the near future, perhaps by 2016.”

North Carolina

In 2008 North Carolina went Democratic for the first time since 1976. And while it flipped back to Republican in 2012, the margin of victory of only 3 percent—51 percent for Gov. Romney to 48 percent for the president—shows that it is more of a swing state now than ever before. The percentage of voters of color in the state rose by 2 percentage points in the four years since 2008 and a total of 4.9 percentage points over the past decade. By 2012, 28 percent of North Carolina’s registered voters were of color, according to the State Board of Elections. Compared to other states, North Carolina has one of the higher percentages of voters of color, which comprise just less than 35 percent of the state’s population. What’s more, North Carolina’s younger population is already heavily made up of people of color, meaning that demographic change will only accelerate in the future. Though North Carolina has rejected Arizona-style anti-immigrant bills in the past, it passed H.B. 36—a mandatory E-Verify law—in 2011.

By 2016 there will be an additional 200,900 eligible Latino voters in North Carolina, accounting for 32.4 percent of all new eligible voters in the state. That number of new voters is two times the size of Gov. Romney’s margin of victory in the state in 2012, which was 97,465 votes. With razor-thin electoral margins and a growing minority population, North Carolina could easily turn reliably Democratic if state policymakers continue down the anti-immigrant path.

The future: Long term

Georgia

Though Georgia has been more of a reliably red state than either Arizona or North Carolina, recent demographic shifts and anti-immigrant politics are changing the conversation in the state. Republicans won Georgia by only 5 percentage points in the 2008 presidential election, and by 8 percentage points in the 2012 presidential election. Georgia has experienced significant demographic changes, as people of color now total 44.1 percent of the state’s population—a 6.7 percent increase over the past decade. And the state’s rapid demographic change is reshaping its electorate. Latinos account for 8.8 percent of the state’s population today and will account for 52 percent of all new eligible voters by 2016. African Americans make up 31.5 percent of the state’s population today, and the African American share of the electorate is more than double the national average.

In April 2011 Georgia passed the Arizona-style anti-immigrant bill H.B. 87, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act. The bill makes it a crime to transport or harbor undocumented immigrants, expands the use of E-Verify for all employers throughout the state by July 1, 2013, and grants the police the power to stop anyone they reasonably suspect to be without status and demand proof of legality. The bill has brought together a coalition of minority groups opposed to measures that lead to racial profiling. Though African Americans are not in danger of being deported for immigration violations, they have been strong allies in opposing such draconian laws. Polling carried out in Georgia, Florida, Ohio, and Virginia found that four in five African Americans support immigration reform that includes a path to citizenship for our nation’s 11 million undocumented immigrants.

With its strong demographic growth among minorities and a tendency to oppose candidates who would perpetuate anti-immigrant laws, Georgia is creating the infrastructure for a challenge to Republican dominance in the not-so-distant future.

Texas

Texas, with its 38 electoral votes, is the state with the second-largest number of electoral votes and a state that has been the anchor of every Republican electoral strategy going back to 1976. Demographically, Texas’s population is diverse, with people of color already comprising the majority of the population, at just more than 55 percent. The Latino population in the state is also among the fastest growing in the nation, comprising 63 percent of the state’s total population growth from 2000 to 2009 and currently comprising 38 percent of all Texas residents. Among the youngest Texans—children under the age of 5—children of color outnumber white children more than 2-to-1, meaning that demographic shifts will only increase in the future. Demographer Ruy Teixeira estimates that 90 percent of all future population growth in Texas will come from people of color.

There will be 905,500 new eligible Latino voters in Texas by 2016, accounting for 58.1 percent of the growth in eligible voters in Texas between 2012 and 2016. Unlike Arizona, however, Texas’s Latino population includes a number of Republicans, that helped elect Sen. Ted Cruz. This fact alone is reason to believe that Texas may not turn blue as quickly as other states such as Arizona. In 2012, 70 percent of Latinos voted Democratic, compared to just 29 percent voting Republican, up from the 63 percent of Latinos who voted Democratic and 35 percent who voted Republican in 2008. But according to national election eve polling by Latino Decisions, 31 percent of all Latino voters in the 2012 presidential election would have been more likely to vote for Gov. Romney had he taken a more positive stance on immigration. It is equally conceivable that these voters will increasingly shift toward the Democrats if Republicans continue to demagogue immigrants. Sen. Cruz acknowledged this fact explicitly, telling The New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza that, “If Republicans do not do better in the Hispanic Community, in a few short years Republicans will no longer be the majority party in our state.”

Conclusion

Even leaving California out of the picture, the states analyzed in this issue brief comprise 137 electoral votes. In 2012 Democrats won 332 electoral votes to the Republicans’ 206, but if Arizona, Texas, North Carolina, and Georgia were to shift Democratic, that would bring the grand total of electoral votes to 412—an insurmountable margin.

Whether these states flip from red to blue is an open question. But two things are abundantly clear: In each of these states, voters of color, particularly Latino voters, are becoming an ever-larger share of the total voting population. These voters care deeply about how both parties talk about immigration, and use it as a litmus test for how candidates from either party feel about their communities as a whole. In fact, immigration reform has become the number one political issue for Latino voters. The voters have spoken, and the message is clear: Getting right on immigration and getting behind real and enduring immigration reform that contains a pathway to citizenship for the 11 million undocumented immigrants living in our country is the only way to maintain electoral strength in the future.

Philip E. Wolgin is a Senior Policy Analyst for the Immigration Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Ann Garcia is a Policy Analyst for the Immigration Policy team at the Center. They would like to thank Patrick Oakford, a Research Assistant at the Center, for his helpful statistics work.