In the wake of the Trump administration’s decision to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and throw the lives of nearly 800,000 recipients into uncertainty, all eyes are on Congress to pass the Dream Act, to provide permanent protection and a pathway to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants who came to the country at a young age.

As a previous Center for American Progress study found, passing the bipartisan Dream Act—S.1615 in the Senate, and H.R.3440 in the House—and putting potentially eligible workers on a pathway to citizenship would add at least $281 billion to the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) over a decade, and as much as $1 trillion over a decade. But the benefits from the Dream Act accrue not just to the nation as a whole, but to individual states as well, and individual industries in those states. This follow-up analysis, and the downloadable data appendix (below) calculates those gains at the state and industry levels.

Definitions

- Conditional permanent residency and lawful permanent residency: Under the Dream Act, the first step on the pathway to citizenship is conditional permanent residency (CPR). After eight years in CPR status, Dreamers can become a lawful permanent resident (LPR)—also known as a green card holder—by completing either higher education, military service, or employment requirements.

- The long run: Immediately after Dreamers receive CPR status under the Dream Act, they are able to work and operate like authorized workers at the same levels of education and work experience. These workers in turn become more productive, increasing their contributions to GDP. Then, in the long run—in this case, over the course of a decade—employers respond to the increases in labor productivity by making capital investments, including buying new tools or machinery and the like, further increasing the gains to GDP.

- Education bump: In this analysis, the education bump refers to a scenario in which we assume that half of those eligible for the Dream Act obtain LPR status through the educational pathway by gaining either an associate’s degree or two years toward a bachelor’s degree. With a greater number of workers now having higher levels of education, their total productivity—and their economic contributions—increase.*

As we discuss in our previous study, although the Dream Act requires everyone to meet certain educational requirements before they can access CPR status, we concentrate here on all of the workers who meet the age and length of residency requirements regardless of educational attainment. This is because we believe that the bill’s passage will be a strong catalyst for people who have not completed the required education to go back to school and do so, and to illustrate that the broader the pathway to status under the bill, the greater the economic benefits.

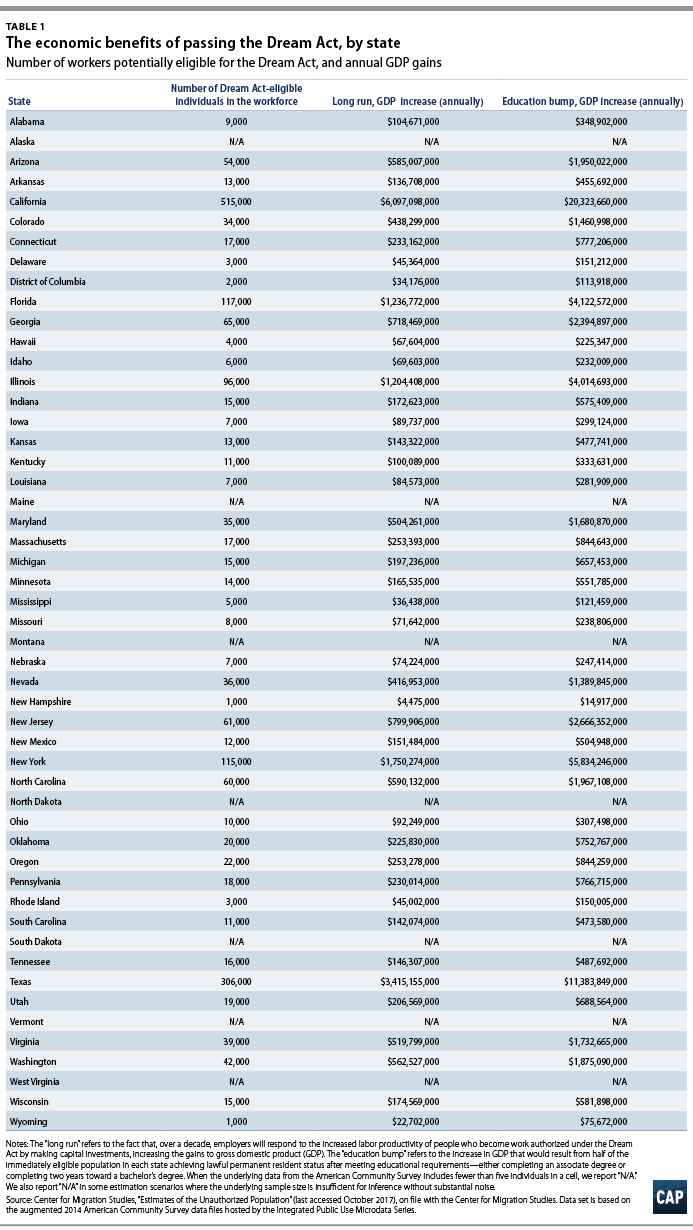

Table 1 lists the number of Dreamers who are potentially eligible for the Dream Act and who are in the workforce, and the economic gains for each state in the long run and with the education bump.

California, with 515,000 immediately eligible workers, would eventually see the biggest gains, of between $6.1 billion in state GDP annually, and, with the education bump, $20.3 billion in state GDP annually. Texas—whose Attorney General threatened to sue to end DACA, had President Trump not ordered the ending of the program on September 5—has 306,000 immediately eligible workers and would see annual state GDP gains between $3.4 billion and $11.4 billion.

But even states with fewer numbers of immediately eligible workers would see big gains from passage of the Dream Act. Georgia, for example, has 65,000 Dreamers in the workforce and would see annual state GDP gains of between $718 million and $2.4 billion. Arizona has with 54,000 Dreamers in the workforce and would see annual state GDP gains between $585 million and $2 billion.

In addition to these statewide economic gains, individual industries within states would also see an economic boost.

In Texas and Florida, for example, two states facing high rebuilding costs from Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, the construction industry would benefit from the Dream Act. In Texas, for example, the sector stands to gain between $562 million and $2 billion each year, and in Florida, between $118 million and $416 million.

Additionally, the leisure and hospitality industry would benefit greatly from the Dream Act. In Nevada, for example, the sector would gain between $79 million and $195 million each year. Additional benefits would accrue to sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and educational and health services.

Given the large benefits to states across the nation and to major industries like construction and leisure and hospitality, Congress should consider passing the Dream Act as soon as possible.

*Author’s note: In this column, we focus on the 1.9 million workers who meet the age of entry and length of residency requirements for the Dream Act. The full data for this scenario, as well as a second scenario that calculates the economic gains for the 1.1 million workers who meet those two requirements, as well as one of the educational requirements—such as being in school, having a high school diploma, or a GED certificate—can be found in the downloadable data appendix.

Ryan D. Edwards is the curriculum coordinator in the data science education program and a research associate in the Berkeley Population Center at the University of California, Berkeley. Francesc Ortega is the Dina Axelrad Perry associate professor in economics at Queens College CUNY. Philip E. Wolgin is managing director for immigration policy at the Center for American Progress.

The authors thank the Center for Migration Studies for providing the census data utilized in this study.