This article contains a correction.

The uptick in the number of children fleeing to the United States has focused attention on the conditions in the Central American countries of Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. In total, these nations have seen 62,998 kids flee to the United States and other neighboring countries. According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, asylum applications in neighboring nations—namely, Mexico, Panama, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Belize*—have risen 712 percent since 2009.

These children are fleeing violence, murder, extortion, rape, and abuse in some of the world’s most violent countries. Just imagine how bad conditions have to be for parents to send their children alone on a dangerous journey in search of safety. And as the violence has gotten worse, the number of child refugees has only increased. Let’s examine the conditions in these countries.

The most dangerous countries in the world

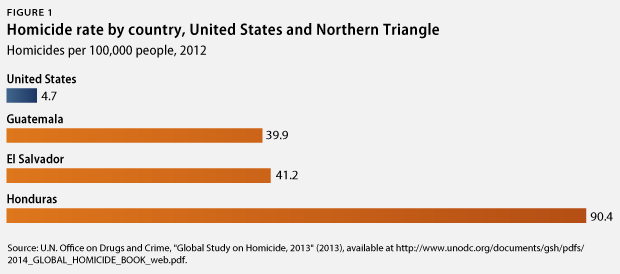

Honduras has the highest murder rate in the world. El Salvador and Guatemala are not far behind, sitting at numbers four and five, respectively. (see Figure 1) To put this in perspective, Guatemala and El Salvador have a murder rate more than 800 percent higher than that of the United States. Meanwhile, Honduras’ murder rate is close to 1,900 percent higher than that of the United States.

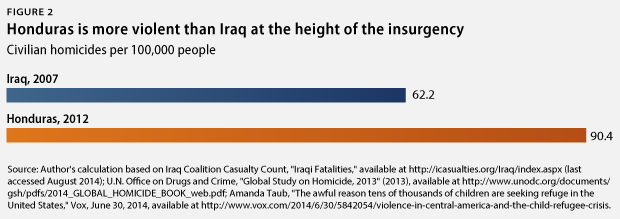

As Vox has pointed out, Honduras’ 2012 murder rate was 30 percent higher than the civilian casualty rate in Iraq in 2007, the year in which the insurgency was at its strongest. (see Figure 2)

Residents of these three countries cannot count on the protection of local police or an independent judiciary to bring claims against those responsible for the violence. Private security forces outnumber police officers by more than four to one in Guatemala. According to the U.S. Department of State, only 5 percent of crimes in El Salvador end in convictions. The State Department warns that “members of the Honduran National Police have been known to engage in criminal activity, including murder and car theft.” In each of these countries, the number of gang members outnumbers the size of the police forces. For example, the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that there are 36,000 gang members in Honduras and only 15,000 police.

Murder capitals of Central America

The three Central American cities with the highest homicide rates are far more dangerous than the worst cities in the United States. (see Figure 3) In 2013, San Pedro Sula, Honduras, had slightly more than 187 murders per 100,000 people. By contrast, in 2012, Detroit, Michigan, saw only 55 murders per 100,000 people—a 342 percent difference.

Not surprisingly, when the U.S. Department of Homeland Security released a map of the cities that have sent the greatest number of child refugees to the United States, the same cities in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador were among those that have sent thousands of children to the United States.

Children and girls are being targeted

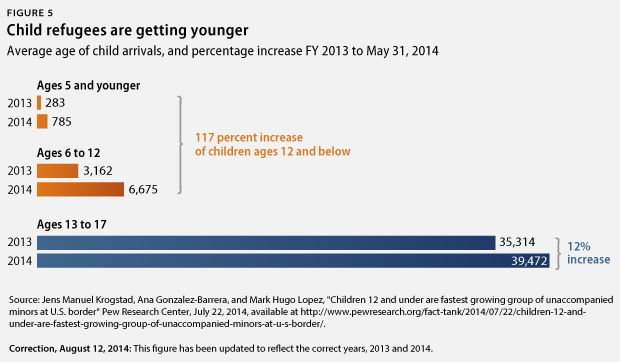

Numerous reports show that gangs and other organized criminal groups are increasingly targeting children. As the Pew Research Center has pointed out, children ages 12 and younger are the fastest-growing group of child refugees. This group has seen a 117 percent increase in arrivals since last year.

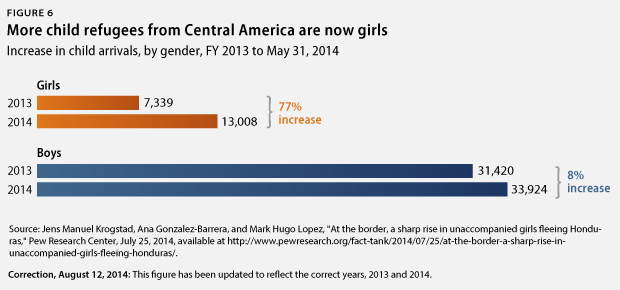

As the U.N. Special Rapporteur on violence against women found in July that violence against women in Honduras “is widespread and systematic.” Between 2005 and 2013, the number of women killed rose by more than 260 percent. In El Salvador, the rate of femicide tripled between 2000 and 2011.

More female children are fleeing than ever before: In just the past year, the number of girls fleeing unaccompanied to the United States has increased 77 percent.

Conclusion

Considering the high levels of violence in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, meeting the challenge of caring for child refugees at our southern border will require both short- and long-term solutions. In the short term, we must allow these children to make their cases for protection and work to cut the amount of time they currently have to wait for their cases to be adjudicated in the immigration courts without sacrificing fairness and due process. In the long term, we must address the root causes of the violence in Central America. Doing so will require more foreign aid, international cooperation, and a commitment from the public and private sectors in these countries to work together to create a robust civil society and to combat organized crime and violence.

The Center for American Progress Immigration team thanks intern Zach Fields and former intern Diego Quezada for their help preparing this article.

*Correction, August 12, 2014: This article has been updated to correct an error in the asylum rate for neighboring countries. The correct countries are Mexico, Panama, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Belize.