In February 2018, the Center for American Progress (CAP) released a proposal for universal health coverage known as “Medicare Extra.”1 Medicare Extra is an enhanced Medicare plan that would be open to all Americans while allowing employers to continue offering coverage. Although Medicare Extra differs in important respects from “Medicare for America”—legislation sponsored by Reps. DeLauro (D-CT) and Schakowsky (D-IL)—these proposals share the same approach.2

CAP contracted with Avalere Health, an independent consulting firm, to model changes in coverage and costs under the Medicare Extra proposal. Avalere specializes in modeling of health policy proposals, using methods and assumptions similar to those of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

Avalere estimates that Medicare Extra would achieve universal coverage by covering 35 million uninsured individuals. Employer coverage would remain a viable option: 121 million employees would choose to remain in their employer coverage.

Even after the coverage expansion, the proposal would reduce national health expenditures by more than $300 billion each year by 2031 relative to current law. The proposal would reduce premium and out-of-pocket costs substantially across income groups for current Medicare beneficiaries; employees who switch to the Medicare plan; individuals currently enrolled in markets under the Affordable Care Act (ACA); and employees who choose to remain in employer coverage.

Avalere modeled three options of the proposal, as specified by CAP, varying only the Medicare Extra cost-sharing levels. Under one version, federal costs would increase by $2.8 trillion over 10 years. As we detail below, this cost is at a level that could be financed exclusively through higher taxes on wealthy individuals and corporations.

Proposal specifications

The following is a summary of the Medicare Extra proposal and specifications that Avalere used in its modeling.3

Medicare Extra would be an enhanced Medicare plan that includes dental, vision, hearing, and reproductive health care benefits. Uninsured individuals, newborns, and individuals turning age 65 would be automatically enrolled.

Premiums and cost sharing (such as deductibles, coinsurance, or copayments) would vary by income on a sliding scale. Premiums would range from zero for families with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level to a maximum of 9 percent of income for families with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty level.

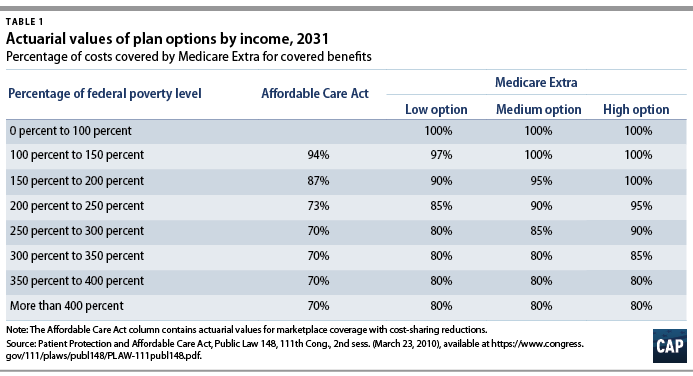

Table 1 presents the cost-sharing schedule. Avalere modeled three options, as specified by CAP, with varying levels of “actuarial value”—the share of costs covered by Medicare Extra, on average. Even the “low-cost” option would boost actuarial values substantially relative to the ACA and relative to the current Medicare program, which has an actuarial value of about 78 percent.4 Avalere estimates that the average actuarial value of Medicare Extra enrollees would be 91 percent. In addition, this comparison of actuarial value understates the generosity of Medicare Extra because it would apply to a more expansive set of benefits.

Employers would have the option to sponsor their own qualified coverage or contribute to the cost of Medicare Extra. Qualified coverage would have an actuarial value of at least 80 percent. Employers would contribute at least 70 percent of the premium of qualified coverage. Alternatively, employers would have the option to contribute 10 percent of their total payroll to Medicare Extra. Small employers with fewer than 100 full-time employees would be exempt from any contribution requirements.

Employees of firms that offer qualified coverage would have the option to switch to Medicare Extra. In such cases, their employer premium contribution would follow them to Medicare Extra.

The current Medicare program, TRICARE (for active military); Veterans Affairs medical care; the Indian Health Service; and the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP) would remain. Individuals who are currently covered by these programs would have the option to enroll in Medicare Extra. The current Medicare program would be improved by adding dental, vision, and hearing benefits and a limit on out-of-pocket costs starting at $5,000 in 2022.

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) would be integrated into Medicare Extra. States would be required to make maintenance-of-effort payments to Medicare Extra based on the amounts that they currently spend on Medicaid and CHIP.

Payment rates to medical providers would generally be based on Medicare rates, except that rates for hospitals would be set at 110 percent of Medicare rates. Medicare Extra payment rates would extend to providers paid by employer plans. Medicare Extra would negotiate prices for prescription drugs on behalf of all payers.

Modeling methodology

Avalere used methods and assumptions similar to those of the CBO where possible.5 To project spending and enrollment under current law from 2022 to 2031, Avalere used the CBO’s 2018 baseline for Medicare, Medicaid, and the ACA, along with the long-term budget outlook. Avalere used behavioral assumptions similar to those of the CBO to model how individuals would respond to changes in costs.

To model employer and employee decisions, Avalere estimated the cost differential between employer-sponsored insurance and Medicare Extra. Avalere then applied the CBO’s assumption for “price elasticity”—the amount by which changes in premiums affect the demand for an insurance plan.

Avalere estimated that setting hospital payment rates at 110 percent of Medicare rates would result in average hospital margins of 2 percent. Avalere used CAP’s assumption that Medicare Extra’s negotiation for prescription drugs would reduce drug prices by 30 percent. Avalere did not estimate the cost of changes to coverage for long-term services and supports.

Results

Avalere estimated changes in coverage, national health spending, consumer costs, and costs to the federal government. Unless otherwise noted, the results presented below are for the “low-cost” option.

Changes in coverage

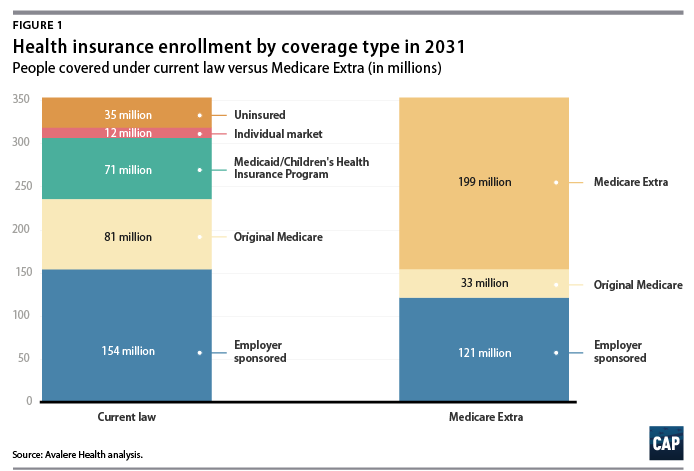

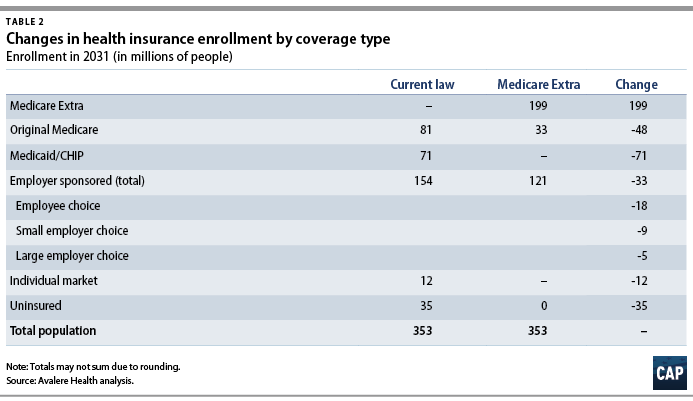

Figure 1 and Table 2 present Avalere’s results for changes in enrollment by type of coverage in 2031. Avalere estimates that the proposal would achieve universal coverage, covering 35 million uninsured individuals, within three years of enactment. By 2031, 232 million Americans, or 66 percent of the population, would be enrolled in Medicare—either original Medicare or Medicare Extra.

Although the current Medicare program would remain an option, many Medicare beneficiaries would switch to Medicare Extra to take advantage of its lower premiums and cost sharing. Because individuals turning age 65 would be enrolled in Medicare Extra automatically, enrollment in original Medicare would shrink and enrollment in Medicare Extra would grow over time.

Employer coverage would remain a stable and viable option under the proposal. Avalere estimates that 121 million employees would continue to be enrolled in employer coverage, while 18 million employees would choose to switch to Medicare Extra. Because Medicare Extra would offer better coverage than most small employers, an additional 9 million enrollees would come from small employers that opt not to offer their own coverage. According to economic analysis, these employees could expect increases in wages because their employers would no longer be paying for health benefits.6 Avalere estimates that only about 3 percent of employees who currently have employer coverage would shift to Medicare Extra because their large employers opt not to offer their own coverage.

Changes in national health spending

Even after covering 35 million uninsured individuals, Avalere estimates that the proposal would reduce national health spending relative to current law. In the third year after enactment, national health spending would grow by 8 percent due to the coverage expansion. But in subsequent years, national health spending would fall relative to current law. By 2031, national health spending would be more than $300 billion lower than under current law.

Changes in consumer costs

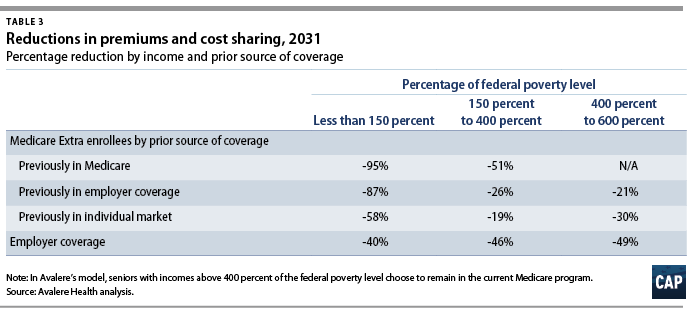

Avalere estimates that the proposal would reduce costs to consumers substantially across income groups. Table 3 presents the percent reduction in premiums and cost sharing by income and prior source of coverage. In general, the savings would be greatest for lower-income families. Because Medicare Extra’s provider payment rates and drug prices would extend to employer plans, employees who choose to remain in employer coverage would also receive substantial savings.

Changes in federal costs

Avalere modeled three options with varying levels of cost sharing, as specified by CAP and detailed in Table 1. Over 10 years, the “low-cost” option would increase federal costs by $2.8 trillion; the “medium-cost” option would increase federal costs by $3.5 trillion; and the “high-cost” option would increase federal costs by $4.5 trillion. Several factors could either increase or decrease federal costs, all else being equal:

- Estimating the cost of coverage for long-term services and supports would increase the federal cost of all options.

- Reducing hospital payment rates to 100 percent of Medicare rates would reduce the federal cost of all options but result in negative hospital margins on average.

- Increasing the actuarial value of Medicare Extra would make it even more attractive relative to employer coverage, causing a greater shift to Medicare Extra. Costs to individuals would decrease and the cost to the federal government would increase.

- Not extending Medicare Extra provider payment rates to employer coverage would increase the cost of employer coverage relative to Medicare Extra, causing a greater shift to Medicare Extra. The federal cost would increase and employees who remain in employer coverage would face higher costs.

- Restricting current Medicare beneficiaries from eligibility for Medicare Extra would reduce the federal cost substantially. Of the $2.8 trillion cost, about $1 trillion derives from improving coverage for current Medicare beneficiaries. Although the proposal could instead make targeted improvements to original Medicare for a lower cost, it would not benefit seniors as much as other populations.

- Restricting employees with employer coverage from eligibility for Medicare Extra would reduce the federal cost substantially. Of the $2.8 trillion cost, about $1 trillion derives from improving coverage for employees who shift to Medicare Extra. However, the program would not be available to all Americans or address the increasing unaffordability of employer coverage. One option would be to limit eligibility to employees whose employer premiums exceed 5 percent of income, but this policy would increase administrative complexity.

At a federal cost of $2.8 trillion, the proposal could be financed exclusively through higher taxes on wealthy individuals and corporations. Premiums (or equivalent tax financing) for middle-income families would not need to exceed a single-digit percentage of income. For example, the cost could be financed with any combination of the following tax revenue options:

- A wealth tax, estimated to raise $2.75 trillion over 10 years7

- Reforms to taxation of capital gains, estimated to raise $2 trillion or more over 10 years8

- A surtax on the very highest incomes, estimated to raise $500 billion or more over 10 years9

- A financial transactions tax, estimated to raise up to $1 trillion over 10 years10

- Repealing the Trump tax cut for corporations and setting the corporate rate at 30 percent (including on overseas profits), estimated to raise $1.7 trillion over 10 years11

- Repealing the Trump tax cuts for business owners and for taxpayers who pay the alternative minimum tax, estimated to raise about $800 billion over 10 years12

- Closing loopholes that enable high-income individuals to avoid Medicare contributions, estimated to raise close to $300 billion over 10 years13

Conclusion

Our analysis finds that Medicare Extra would:

- Achieve universal coverage

- Enroll the majority of the population in a Medicare plan

- Allow employees a choice of plan

- Reduce national health spending

- Reduce consumer costs substantially across income groups

- Increase federal costs by less than $3 trillion

- Hold premium or tax financing to single-digit percentages of income for middle-income families

- Reduce the cost of hospitals without resulting in negative margins

- Reduce the cost of prescription drugs

Designing a universal health care proposal involves many tradeoffs. This proposal is an approach with policy dials that can be adjusted to achieve the desired outcomes or a pathway to an end state. In the coming years, Congress must find the balance that can be enacted into law as soon as possible.

This analysis illustrates that meeting the urgent need of universal coverage is clearly within our reach. The wealthiest nation on earth must finally join other developed nations to guarantee health care as a right, not a privilege.