The so-called Health Policy Consensus Group—led by former Sen. Rick Santorum (R-PA) and composed of several conservative think tank groups—just released a new plan to repeal the Affordable Care Act.1 The group has been working with Senate Republicans, a group of corporations, and the White House, which supports the plan. Some Senate Republicans aim to take legislative action on the plan by the end of August.2 Their first step would be to pass a budget bill that provides them with the authority to pass the repeal bill on a party-line vote. The House Budget Committee is scheduled to begin that process this week.3

Although this is a new plan, it merely recycles some of the worst elements of the failed Graham-Cassidy repeal bill4—which experts consider the “the most harmful” repeal bill.5 Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would lead to the same disastrous results:

- Millions of Americans would lose health care coverage.6

- Protections for pre-existing conditions would be decimated.

- Costs would increase for lower-income, older, and sick Americans.

- Massive disruption would occur, causing insurers to drop out of marketplaces.

Based on the plan’s specifications and the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) updated baseline of ACA funding under current law,7 the Center for American Progress estimates that Graham-Cassidy 2.0 could cut ACA funding for health coverage by 31 percent by 2028 and by 26 percent from 2022 to 2028.

In addition, because states could not use block grant funding to re-establish Medicaid expansion programs, Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would slash funding for Medicaid by $649 billion from 2022 to 2028.

The plan would decimate protections for pre-existing conditions

As with all previous repeal bills, Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would eliminate protections for millions of people with pre-existing conditions.8

Repeals ACA protections in all states

Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would repeal ACA protections that:

- Require insurance companies to cover essential benefits, such as maternity care, prescription drugs, mental health care, and treatment for opioid addiction

- Prohibit insurance companies from charging higher premiums based on pre-existing conditions

- Limit how much insurance companies can charge older individuals compared with younger individuals

- Prohibit insurance companies from imposing lifetime and annual limits on all essential benefits

As a result, insurance companies could:

- Eliminate coverage of maternity care, prescription drugs, mental health care, and treatment for opioid addiction

- Charge people with pre-existing conditions much higher premiums

- Charge older individuals much higher premiums

- Impose lifetime and annual limits on essential benefits that are no longer required

Younger, healthier individuals would likely gravitate to skimpier plans, losing protections for when they ultimately become sick. Because Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would repeal the requirement for a single risk pool, the risk pool would be fractured into two risk pools—one for unregulated plans and one for ACA plans. Older, sicker individuals would be left behind in the ACA risk pool, driving up premiums and, according to the nonpartisan American Academy of Actuaries, “destabilizing the market.”9

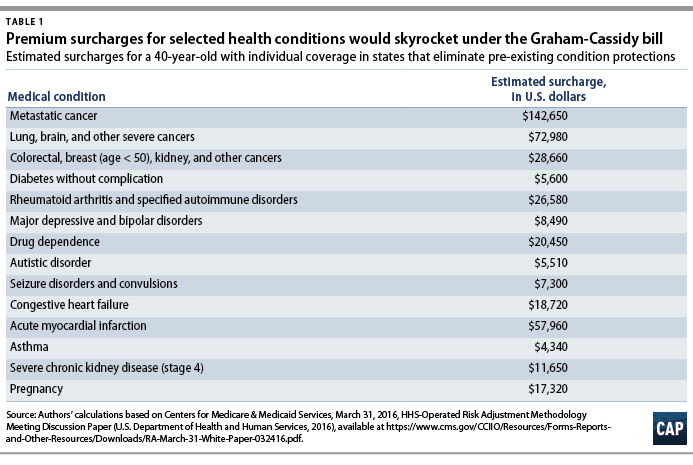

In states that allow insurance companies to charge higher premiums for health conditions, premium costs for people with pre-existing conditions would increase by thousands and tens of thousands of dollars. Using data on the cost of various conditions relative to a healthy person, CAP previously estimated that premiums for 40-year-old individuals would increase by $4,340 for asthma, $5,600 for diabetes, $17,320 for pregnancy, $20,450 for opioid addiction, and $28,660 for breast cancer. (see Table 1)10

Provides inadequate funding to offset costs

As with previous repeal bills, Graham-Cassidy 2.0 includes funding for high-risk pools in an attempt to protect people with pre-existing conditions. These pools would quarantine sicker enrollees into a separate market.11 Prior to the ACA, enrollees in high-risk pools often faced much higher premiums; lifetime and annual limits on coverage; and waiting periods for the first six to 12 months of enrollment before their pre-existing conditions could be covered.

The CBO previously assessed that, even with high-risk pools, coverage for pre-existing conditions would be “extremely expensive.”12 Based on historical experience, “the funding available to help provide coverage for excluded high-cost services would be insufficient in some cases even if a special program was designed for that purpose.”

Similarly, funding to compensate people with pre-existing conditions for skyrocketing premiums would have minimal effects. Last year, the CBO assessed the adequacy of the House repeal bill’s $8 billion fund to offset premiums for people with pre-existing conditions:13

Although CBO and JCT expect that federal funding would have the intended effect of lowering premiums and out-of-pocket payments to some extent, its effect on community-rated premiums would be small because the funding would not be sufficient to substantially reduce the large increases in premiums for high-cost enrollees. To evaluate the potential effect of the $8 billion fund, looking back at the high-risk pool program funded by the ACA prior to 2014 is useful. Within two years, the combined enrollment of about 100,000 enrollees in that program resulted in federal spending of close to $2.5 billion.

Massive funding cuts would cause millions to lose coverage

As with the original Graham-Cassidy bill, Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would repeal the Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies and replace them with severely underfunded block grants to states. The document states that “initially, the grants would be based on the amount of ACA spending as of a fixed date.”14 According to a leaked outline that was verified by reporters, the initial cut to ACA funding for health coverage could be 20 percent.15 We assume the block grants begin in 2022, a timeline that is equivalent to that of the original Graham-Cassidy bill. We also assume that after the initial cut in 2022, total block grant funding grows at the rate of consumer inflation (CPI-U).

Under its May 2018 baseline, the CBO estimates that funding for Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies will equal $150 billion in 2022 and $1.22 trillion from 2022 to 2028.16 Under Graham-Cassidy 2.0, an initial cut of 20 percent in 2022 would result in block grant funding of $120 billion in 2022. Because health care costs grow faster than inflation, indexing this amount by CPI-U would result in steeper cuts over time, resulting in a 31 percent cut by 2028. Block grant funding would equal $903 billion from 2022 to 2028, a cut of $320 billion, or 26 percent, over that period.

Under Graham-Cassidy 2.0, at least 50 percent of block grants must be spent on private insurance—significantly limiting states’ ability to cover people through Medicaid. In addition, states would not be able to use their block grant funding to re-establish Medicaid expansion programs. Under its May 2018 baseline, the CBO estimates that federal spending for Medicaid expansion will equal $649 billion from 2022 to 2028. Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would eliminate this funding—and any replacement program that states manage to set up would likely fall short. Finally, the plan would require states to offer vouchers for private insurance as an alternative to Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

Because Medicaid is much more cost-efficient than private insurance and offers more affordable and generous coverage,17 these funding cuts and restrictions would result in significant coverage losses and increased costs for lower-income families.

States that expanded their Medicaid programs—such as Alaska and Maine—would be hit particularly hard and face funding cuts much deeper than the national cut. Assessing the impact of the original Graham-Cassidy bill on people with incomes between 100 percent to 400 percent of the federal poverty level, the CBO concluded:

States that expanded Medicaid would be facing large reductions in funding compared with the amounts under current law and thus would have trouble paying for a new program or subsidies for those people.18

Graham-Cassidy 2.0 would likely cut total ACA funding by 26 percent then spread that smaller amount across multiple purposes and among many more people up the income scale. The inescapable math is that the plan would slash funding targeted toward lower-income populations, causing massive loss of coverage.

The plan would transfer tax benefits to the wealthy

At the same time that Graham-Cassidy 2.0 slashes funding for lower-income populations, it transfers much of that money to expand health savings accounts (HSAs), which function as tax shelters for higher-income people. Research and tax data demonstrate that HSAs primarily benefit upper-income households, since these households are more likely to use the accounts; have more money available to invest in them; and receive a greater tax benefit from them.19 Replacing Medicaid and ACA tax credits with HSAs—which are paired with high-deductible plans—would significantly increase costs for lower-income and lower-middle-income families.

Massive disruption would cause insurer withdrawals

Replacing Medicaid expansion and ACA marketplaces and revising market rules would cause massive disruption. Before the transition, insurers would face massive uncertainty about how states would implement new programs and revise market rules. As a result, the CBO assesses, “[S]ome areas would probably have no insurers offering policies in the nongroup market until the new market rules were clear and insurers had enough time to adapt to them.”20

In addition, the nonpartisan American Academy of Actuaries also warns of insurer withdrawals:

In light of this uncertainty, insurers might reconsider their current participation in the market and some may choose to exit in the near term. This could lead to more market disruption and loss of coverage among individual market enrollees.21

Finally, it would be extraordinarily difficult for some states, including Alaska and Maine, to build the necessary infrastructure from scratch. In the CBO’s assessment:22

To establish its own system of subsidies for coverage in the nongroup market related to people’s income, a state would have to enact legislation and create a new administrative infrastructure. A state would not be able to rely on any existing system for verifying eligibility or making payments. It would need to establish a new system for enrolling people in nongroup insurance, verify eligibility for tax credits or other subsidies, certify insurance as eligible for subsidies, and ultimately ensure that the payments were correct. Those steps would be challenging, particularly if the state chose to simultaneously change insurance market regulations.

The government had four years to build the infrastructure for HealthCare.gov, whereas states could only have two years to build the infrastructure for their programs from scratch. Widespread and prolonged operational failure would likely result, leaving consumers helpless.

Moreover, the block grant structure would radically politicize health care funding, engineering a massive redistribution across states based on political factors and opening the door to corruption and political favors.

Conclusion

Americans have overwhelmingly rejected repeal, and recent polling makes clear that they will hold members of Congress accountable for any revival.23 Even if Congress fails in this latest attempt, the release of Graham-Cassidy 2.0 previews the agenda of the current congressional majority in 2019. The health care of millions of Americans hangs in the balance.

Topher Spiro is the vice president for Health Policy at the Center for American Progress.