In this ongoing series, we analyze the recently released Medicare physician payment database to identify wasteful spending by Medicare and seniors, including on treatments proven ineffective or in cases where equally effective alternatives to a high-priced treatment exist.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or CMS, recently released Medicare physician payment data for the first time in decades. This release generated a great deal of media coverage, both of the doctors billing the most to Medicare and also of the most expensive health care services.

One of the highest-volume costs in the database is for Lucentis, a drug used to treat agerelated macular degeneration, or AMD, a form of blindness that affects the elderly. Last year, a Washington Post investigation highlighted the unsettling fact that, while an equally effective alternative drug, Avastin, costs about $50 per injection, many ophthalmologists continue to prescribe and administer Lucentis—which is priced 40 times higher, at about $2,000 per injection. This price difference is particularly staggering given that Lucentis and Avastin are both recommended to be injected monthly, meaning these prices represent repeated costs to patients and Medicare over time.

Background

Multiple studies have proven that Avastin and Lucentis are equally effective at treating AMD, with no difference in clinical outcomes between the two drugs. Nevertheless, Lucentis is still prescribed and administered more than half a million times per year. One reason for the continued use of Lucentis is that Avastin was originally developed as a cancer drug and is therefore sold in larger doses than are required for treating AMD.

Its manufacturer, Genentech, refuses to repackage it for sale in smaller doses, so pharmacists must currently repackage the drug manually in a sterile environment. Genentech has strong financial incentives to discourage the use of Avastin for treating AMD—it is the same company that manufactures Lucentis, which generates substantially higher profits because the production costs of the two drugs are roughly comparable.

Ophthalmologists also have financial incentives to prefer Lucentis. Since Medicare reimburses doctors for drugs at the average sales price plus 6 percent, ophthalmologists receive $120 above the sales price for Lucentis, compared to only $3 for Avastin.

Potential savings for Medicare and seniors

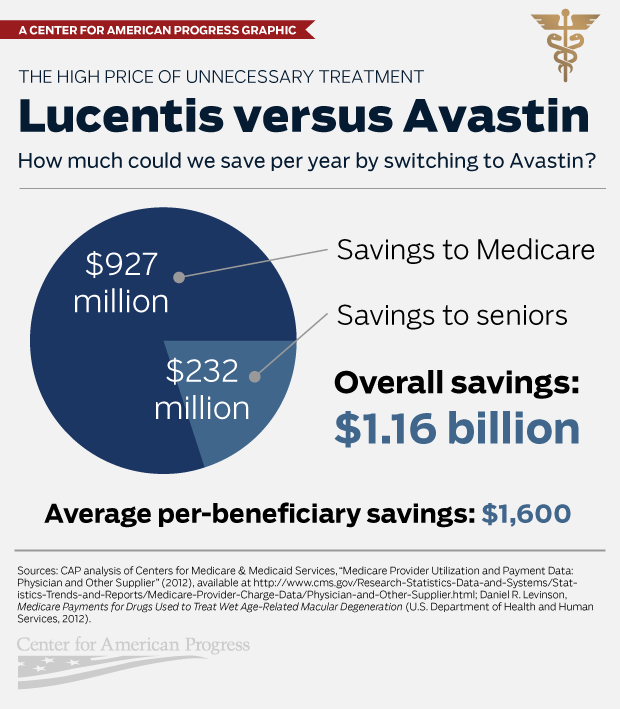

Medicare spent $950.8 million on Lucentis injections in 2012. If ophthalmologists had treated all of these cases with Avastin, Medicare would have spent only $32.3 million—saving $926.5 million.

Medicare beneficiaries, meanwhile, would have saved an additional $231.6 million in out-of-pocket costs, such as co-insurance. While the CMS database does not include patient data, it does indicate that 143,980 unique Medicare beneficiaries received Lucentis injections. If all of these beneficiaries received the same number of Avastin injections, savings would total $1,600 per senior. The exact level of savings per senior would depend on the number of injections received by each beneficiary; while many seniors have supplemental coverage that covers co-insurance, premiums for this coverage would be lower if it did not have to cover these costs.

Savings to Medicare and beneficiaries combined would have totaled $1.16 billion in 2012. This is substantially higher than a 2011 Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, estimate, which calculated total savings of $1.4 billion over two years for Medicare and beneficiaries if they switched entirely to Avastin. The HHS estimate relied upon a different dataset and extrapolation from a smaller sample size.

Conclusion

Despite the substantial limitations of the CMS database, this increased transparency provides a powerful tool to highlight wasteful spending and overtreatment. In a potent example of the perverse incentives in our health care system—one company’s packaging decision costs Medicare and seniors $1.16 billion per year. Lucentis not only offers no benefit over Avastin for patients, but it also represents an inefficient and wasteful use of taxpayer dollars.

Topher Spiro is the Vice President for Health Policy at American Progress. Thomas Huelskoetter is the Special Assistant for Health Policy at the Center for American Progress. Gina Phillipi is an intern on the Health Policy team at the Center.

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Center for American Progress.