Weak gun laws have been directly tied to higher rates of gun violence, and Missouri has some of the weakest in the country. According to an analysis by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence,1 the strength of Missouri’s gun laws ranks second to last in the United States. The state has further weakened its gun laws in recent years by passing dangerous bills, such as one that repealed a law requiring a permit to purchase a firearm.2 And during the 2018 legislative session, state legislators pushed for yet another gun bill that would allow more individuals to carry firearms in Missouri’s public spaces.3

Such weakening of laws has had a detrimental effect on community safety. A person is killed with a firearm every 10 hours in Missouri, making gun violence an urgent public health priority.4 In this issue brief, the authors address four aspects of gun violence and gun-related crimes in Missouri that are alarming or above the national average:

- Missouri’s rate of gun homicides, particularly in urban settings and communities of color, is among the highest in the nation.

- Women in Missouri are killed with guns by intimate partners at high numbers.

- Children in Missouri die from gun violence at rates that are among the highest in the nation.

- Gun theft is a substantial problem in Missouri.

Given Missouri’s alarming gun violence statistics, it is important for state elected officials to reject proposals that would further weaken its gun laws, as well as to consider stronger policies to reduce the already high levels of gun violence in the state. After addressing the above four aspects of the state’s gun violence, this issue brief provides steps, both legislative and executive, to reduce gun violence in Missouri.

Missouri’s history of enacting weak gun laws

Missouri’s gun laws are among the weakest in the nation, behind only Mississippi and tied with Kansas.5 The state has become a clear case of how weakening state gun laws can have negative consequences for the population.6 In 2007, Missouri repealed its permit-to-purchase (PTP) law, which required all handgun purchasers to have a valid license that they could obtain only after passing a background check. Gun homicides in Missouri increased by 25 percent in the three years following the repeal of the law—from 2008 to 20107—and more Missouri guns were recovered in crimes in neighboring states. The number of guns sold in Missouri that were later recovered in connection with criminal investigations in the neighboring states of Iowa and Illinois rose by 37 percent, from before the PTP repeal in 2006 to four years after its repeal in 2012.8

This is not the only instance in which the state has weakened its gun laws. The legal age limit to obtain a concealed gun permit was lowered from 23 to 21 in 2011,9 and it was lowered again to 19 in 2014.10 And more recently, in 2016, overriding Gov. Jay Nixon’s (D) veto, Missouri legislators enacted S.B. 656 to allow permitless carry of concealed guns.11 Thus, effective January 1, 2017, Missouri allows individuals in Missouri over age 19 to carry concealed guns without a permit in most locations.12

Despite the alarming consequences of weak gun laws, Missouri state legislators recently pushed for a bill that would further weaken the state’s gun laws. Exacerbating permitless concealed carry,13 Missouri House legislators introduced H.B. 1936, which proposes to amend the locations where concealed carry is restricted or prohibited.14 H.B. 1936—described by its critics as the “guns everywhere bill”—would allow individuals to carry concealed guns in more places, including schools, churches, bars, and day cares.15 Despite the national movement toward stricter gun laws fueled by the Parkland shooting in February 2018, the Missouri House Committee on Rules – Legislative Oversight passed this bill during the 2018 legislative session.16 It was largely supported by the unsubstantiated rationale that having more guns makes the community safer; however, this myth has been debunked by evidence showing that expansive concealed carry laws are in fact associated with increased violent crimes.17

Missouri’s alarmingly high rate of gun homicides

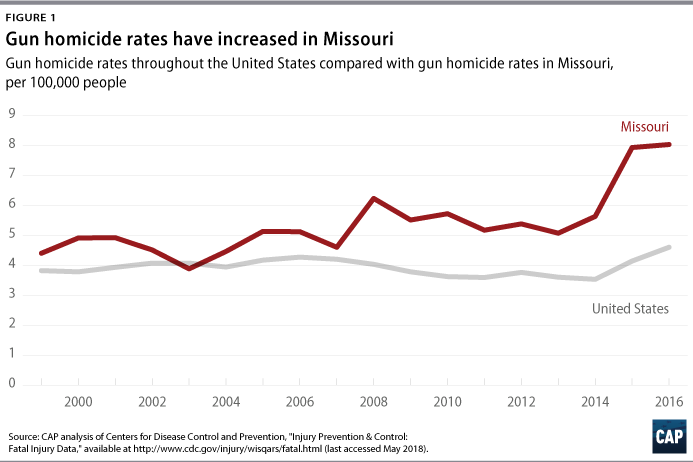

Weak laws in Missouri have made guns easily accessible and have had a direct impact on gun homicides. A 2014 analysis estimated that when Missouri eliminated its permit-to-purchase requirement, which included a background check, gun homicides increased by 25 percent.18 More alarming is the fact that since the publication of this 2014 analysis, gun homicide rates in Missouri have continued to rise dramatically. During 2016, for example, Missouri reached its highest rate of gun homicides since 1999.19 Overall, during 2016, the state’s rate of gun homicides was 75 percent higher than the national rate, ranking fourth highest in the country.20

The plight of gun violence, moreover, disproportionately affects Missouri’s urban areas and communities of color. In addition to easy access to guns, factors such as a lack of employment and a breakdown in police-community relations contribute to higher rates of urban violence. Ninety-three percent of gun homicides in 2016 occurred in urban settings, with 40 percent taking place in St. Louis alone.21 In addition, while African Americans made up close to 12 percent of the state population in 2016, they suffered 67 percent of gun homicides in the state.22

Women in Missouri are killed with guns by intimate partners in high numbers

In the United States, women are more likely than men to be murdered by someone they know. In many cases, this person is an intimate partner.23 Research has shown that the combination of gun access and domestic violence increases the risk of fatal violence toward women. A 2003 study concluded that women living in a household with a gun and a history of domestic violence are 500 percent more likely to be killed by an intimate partner.24 According to an analysis of FBI data, 34 percent of women murdered in the United States from 2006 to 2015 were killed by an intimate partner, and 55 percent of those women were murdered with a firearm.25

The risk of gun homicides against women by an intimate partner is slightly higher in Missouri. Close to 33 percent of women murdered in Missouri from 2006 to 2015 were killed by an intimate partner. Among these women, close to 58 percent were killed with a firearm. In fact, according to information from the FBI, from 2006 to 2015, at least 157 women were fatally shot by an intimate partner in the state of Missouri—or 1 every 23 days.26

Similar to gun homicide rates, there are racial disparities in intimate partner gun homicides of women in Missouri. Although African American women represented close to 12 percent of the female population in Missouri from 2006 to 2015, 31 percent of the 157 women fatally shot by an intimate partner during that period were African American.27

But these tragedies are more than just numbers. They are also stories that have a profound effect on family members and their communities. On March 16, 2009, a 26-year-old Kansas City man went to his ex-girlfriend’s apartment and fatally shot her. The perpetrator also killed his ex-girlfriend’s two young nephews, as well as her current boyfriend.28 And former Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Jovan Belcher made national headlines on December 1, 2012, when he shot and killed his girlfriend in front of his mother and 3-month-old child and shot himself soon after.29

Missouri’s high rate of gun-related child fatalities

Nearly 1,400 children died each year from gun violence in the United States from 2007 to 2016.30 Gun-related incidents are the third-leading cause of death overall among U.S. children and the second-leading cause of injury-related death following motor vehicle injuries.31

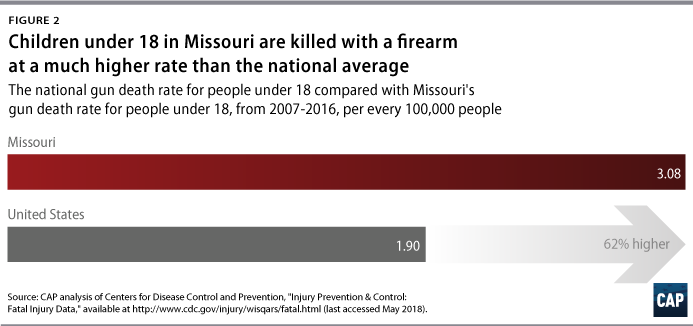

Children in Missouri die from guns at a rate that is among the highest in the nation. From 2007 to 2016, Missouri’s overall gun-related child death rate was the sixth highest in the nation—62 percent higher than the national rate.32 Specifically, during the same period, the child gun homicide rate in Missouri was the third highest in the nation,33 at a rate of 1.91 gun homicides per every 100,000 children ages 0 through 17—72 percent higher than the national rate.34 Studies have reported that the majority of young children under age 12 who are killed in gun homicides are bystanders in intimate partner violence incidents.35 Therefore, it is noteworthy that Missouri has high rates of both child gun homicide and intimate partner gun homicides of women, as discussed above.

In addition, while unintentional deaths comprise only 8 percent of overall gun-related child deaths, Missouri has the 10th-highest rate of unintentional child gun death among the 28 states from which data were available for the period of 2007 to 2016.36 Recently, in March 2018, a 5-year-old boy accidentally shot and killed his 7-year-old brother after finding a gun in the drawer while looking for candy in his home in St. Louis.37

Missouri’s gun theft problem

There is growing apprehension about the number of firearms being stolen in the United States. Law enforcement officers have expressed concerns about the risk of stolen guns, as these guns end up being used to commit crimes. For example, from 2010 to 2015, more than 9,700 guns that were reported lost or stolen from a gun store were recovered by police agencies in connection with a crime.38

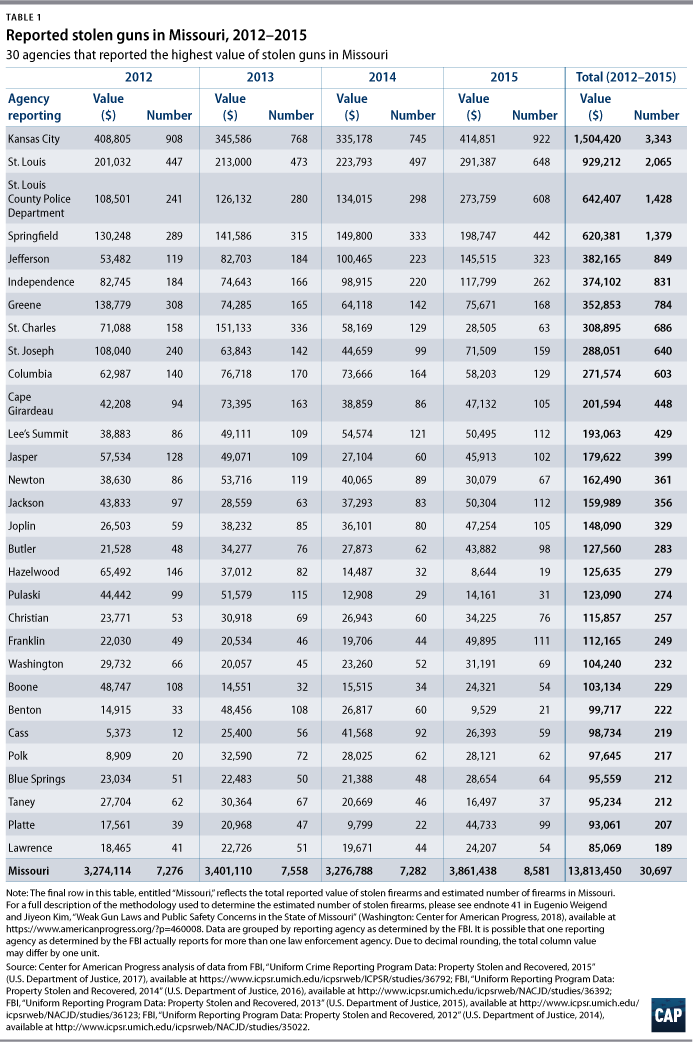

Nonetheless, while the number of firearms stolen from gun dealers is alarming, most guns are stolen from private gun owners. Nationally, it is estimated that close to 1.2 million guns were stolen from private owners from 2012 to 2015.39 The scale of this issue varies from state to state: When compared with other states, Missouri had the 14th-highest number of stolen firearms in the country,40 with an estimated 30,697 firearms stolen from 2012 to 2015—or 1 gun stolen every 68 minutes.41 FBI data suggest that close to 88 percent of stolen firearms in Missouri are never recovered.42 Many of these guns could be used to commit crimes within the state or be illegally trafficked to other parts of the country.

Within Missouri, the problem varies widely for state law enforcement agencies, which submit data annually to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports indicating the dollar value of property reported stolen in their respective jurisdictions. The data suggest that 30 local or county agencies reported close to 60 percent of the total value of stolen firearms in Missouri.43 Of this share, the agency of Kansas City alone reported close to 11 percent of the total value of stolen firearms in the state.

Steps to reduce gun violence in Missouri

To protect victims of gun violence in the state, Missouri should reject any bill that would further weaken its gun laws. Legislation such as the “guns everywhere bill” is based on myths, and if implemented, such laws would endanger the people of Missouri—particularly vulnerable populations such as communities of color, women, and children.

Legislative actions

Reinstate permit-to-purchase laws, along with a background check requirement. As mentioned above, there is overwhelming evidence showing the link between the removal of PTP laws and the dramatic increase in Missouri’s rate of gun homicides.

Protect women from domestic violence offenders. To protect women, Missouri legislators should pass laws that bar individuals convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence or stalking crimes and those subject to a domestic violence restraining order from being able to purchase firearms and ammunition.44 Legislators should also pass legislation requiring abusers to surrenders any guns at the time that possession becomes prohibited. Finally, legislators should pass laws to close the “boyfriend loophole” and prohibit abusers in dating partner relationships from buying firearms.45

Implement better child access prevention laws. Except for Mo. Rev. Stat. § 571.060.1(2)—which prohibits recklessly selling a gun to minors under age 18 without the consent of the minor’s parent or guardian46—Missouri does not have any child access prevention laws that penalize individuals for negligently storing guns where a child can gain access. To reduce child mortality by guns, legislators in Missouri should pass such a law. Evidence indicates that these laws are strongly associated with lower levels of suicide by gun and unintentional gun deaths among young people and children.47

Pass legislation that requires gun owners to report any lost or stolen firearms to law enforcement agencies. Laws in Missouri do not require gun owners to report to local law enforcement agencies when a gun is stolen or lost. This facilitates gun trafficking and removes gun owners’ accountability when their guns are connected to a crime.

Executive actions

Fund rigorous surveys to identify specific communities at risk of gun violence and projects to develop the most effective methods to reach such communities. Data presented in this brief suggest that specific populations—communities of color, women, and children—are at a heightened risk of gun violence. More rigorous state-level surveys and studies can better identify the exact needs of these communities and uncover hidden risks. Also, community-based projects are necessary to identify and develop the best methods to reach those communities most in need.

Provide preventive services to individuals at greatest risk of exposure to gun violence. Individuals affected by or involved in gun violence are often predisposed to other disadvantages, such as poverty and exposure to violence in general.48 Targeted preventive strategies providing social services, support, or any necessary treatment can be effective for both protection and deterrence. In this regard, cities in Missouri should provide funding to replicate intervention programs such as Cure Violence, Hospital-based Violence Intervention, and Group Violence Intervention. These strategies have been successful at reducing violence in many urban communities.49

Implement an effective interagency program to reduce gun homicide. The Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission (MHRC)50 is an example of such a program. It is a multistage interagency homicide incident review system that includes the following components: real-time police review of homicide incidents; a monthly criminal justice panel that reviews the incidents; a service provider review that identifies contributing factors to the incidents; and community review that informs the public and invites public comments on the incidents. The MHRC has been successful in reducing fatal and nonfatal shootings,51 and thus provides an effective model for Missouri state officials to consider.

Gun violence in Missouri is an urgent public health problem. Every 10 hours, a person is killed with a firearm in Missouri. State elected officials have an important duty to protect their communities by rejecting dangerous bills and implementing common-sense measures to reduce the number of gun deaths.

Eugenio Weigend is the associate director for Gun Violence Prevention at the Center for American Progress. Jiyeon Kim is in her final year of the J.D. program as a Dean’s Fellow and Webster Scholar at Washington University in St. Louis School of Law.