The epidemic of gun violence against America’s youth is more than just a disturbing data point. For each bullet fired, there are multiple stories of lives changed forever. When he was just 6 years old, Missouri State Rep. Bruce Franks Jr. saw his brother shot in front of their neighbor’s home.4 Nevada activist Mariam El-Haj witnessed the shooting of her mother by her estranged father, who then turned the gun on Mariam.5 Oregon youth mentor Jes Phillip’s siblings have all had close calls—she has three younger sisters who were present at the Reynolds High School shooting in Troutdale, Oregon, and two bullets landed next to her brother’s bed when they came through her family’s apartment wall during a neighborhood shooting.6 Nineteen- year-old student Eli Saldana, a member of the Native American community living in Chicago, was shot on his walk home from work.

These stories of gun violence are all too common among young Americans. The United States’ gun violence epidemic disproportionately ravages young people, particularly young people of color. In short, gun violence is shattering a generation.

Young people are not simply victims of gun violence in this country, they are among the leading voices calling for change to the nation’s weak gun laws and deadly gun culture. Organizers of the Black Lives Matter movement; survivors of the Parkland shooting; youth organizers working in cities hardest hit by gun violence, such as Chicago, Baltimore, and St. Louis, have all lent their voices to an increasingly loud call to action.

These young people do not just want to reform gun laws—they are also demanding that the issue of gun violence be examined as part of a complex and intersectional web of issues that also include community disinvestment, criminal justice reform, and policing. They are advocating not only for solutions to make schools safer from mass shootings but also for holistic and intersectional solutions that will help make all communities safer.

This report breaks down how gun violence is affecting young people, and how young activists are rising to build an intersectional movement working for solutions. It examines the specific impact of gun violence on young people and considers both how young people as a collective are disproportionately affected and how different communities of young people share different aspects of the burden of this violence. This report also highlights examples of young people leading the advocacy efforts around this issue and discusses a number of policy solutions that are crucial to reducing gun violence, reforming the criminal justice system, improving police-community relations, and encouraging reinvestment in impacted communities.

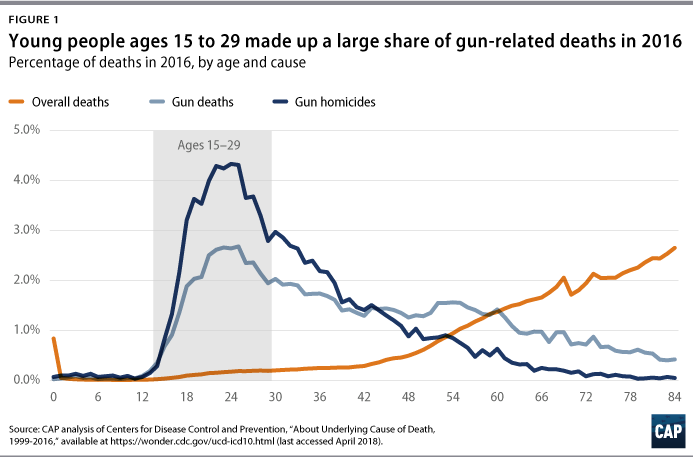

Young people make up a very small percentage of all deaths in the United States each year. Consider 2016: That year, more than 2.7 million people in the United States died, with the top-three leading causes of death being heart disease, cancer, and unintentional injuries.7 Of these 2.7 million deaths, only 2.2 percent were individuals between the ages of 15 and 29.8 However, looking only at deaths caused by gunfire, the picture changes dramatically. Young people in this age range accounted for 31 percent of all gun deaths in 2016 and nearly 50 percent of all gun-related homicides.9

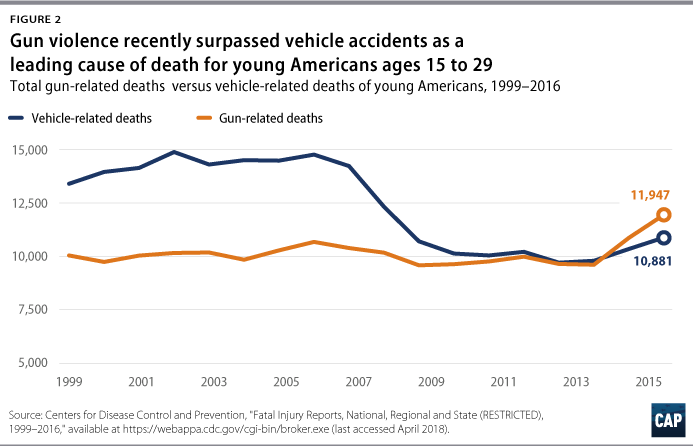

Gun violence recently surpassed motor vehicle accidents as a leading killer of young people in the United States and was second only to drug overdose. Following decades of advocacy and policymaking to make automobiles and driving safer, the number of young people killed in car accidents has steadily declined. In contrast, years of relative inaction to reduce U.S. gun violence has led to the number of gun deaths among young people between the ages of 15 to 29 to rise, with 11,947 individuals in this age group dying as the result of gun violence in 2016.10

DeJuan’s story

The summer before he started his senior year of high school in 2005, DeJuan Patterson, now 29, was walking home from work when he was approached by a man who robbed him of his belongings and then shot him in the head. His body went into shock, but when he gathered the strength to open one of his eyes, he stared into the barrel of another gun, this time from the Baltimore police.

Patterson has relived that harrowing incident in his mind countless times and wondered what would prompt a police officer to revictimize a man sprawled on the ground bleeding from a gunshot wound to the head instead of offering help. Patterson understands that what he went through is something all too familiar to many black men, many of whom are victims of gun violence in their neighborhoods and at the hands of police. And while Patterson can make no sense of the police officer’s actions that night, he has focused his energy on speaking up against gun violence, for the need for policing reform, and for investment in youth outreach and community engagement.

Today, 13 years after his life-changing experience, Patterson serves on the Fight4AFuture National Leadership Council and is a leader in his Baltimore community.11

Young people are also overrepresented in another category of gun deaths: fatal shootings by police. The use of lethal force by police has been a top concern in many communities for decades and gained increased attention nationwide in the wake of a spate of fatal shootings of unarmed black men in recent years. The criminal justice system deems most fatal shootings by police officers justified as a lawful use of force. Each of these deaths, however, has a significant impact on the community and its relationship with law enforcement—particularly in communities of color that have a deep and complicated history with their local police department. These police shootings are a core part of what gun violence looks like in many communities across the country.12 According to data collected by The Washington Post, in the nearly 3,300 fatal shootings by police from January 2015 through April 2018, approximately 31 percent of the victims were between the ages of 18 and 29. This means that a young person is shot and killed by a police officer in the United States almost every day.13 Out of the young people fatally shot by police officers, 34 percent were African American, among which at least 12 percent were unarmed.14

In addition, young people are at a heightened risk for being victims of violent crime involving a gun. Data from the National Crime Victimization Survey suggests that close to 840,000 young people between the ages of 15 and 29 were victims of violent crimes involving a firearm from 2012 to 2016.15 When compared to other age groups, young people present the highest rate of victimization at a rate that is 69 percent higher than the national average.16

Jes’ story

Jes Phillip, 28, moved with her family from Micronesia to Portland, Oregon in 2008. As a teenager at the time, she left behind a country that experiences little to no gun violence to live a city neighborhood where gun violence was—and still is—part of daily life. Phillip made it to college without directly experiencing a shooting herself. However, all of her siblings were directly affected by gun violence in their school. On June 10, 2014, a student walked into Reynolds High School where Phillip’s three younger sisters were present, armed with two guns, nine ammunition magazines, and a knife. A teacher was injured, and a student was shot and killed before the gunman committed suicide.17

Gun violence touched Phillip’s life again just a year later when two stray bullets tore through the wall of her family’s apartment, landing next to her brother’s bed. That same day, several bullets peppered different apartments in her neighborhood, killing one of her neighbors.18

Phillip, now a mother and youth mentor, lives daily with the fear of gun violence, as it is part of her routine. She is afraid that this issue continues to threaten her child, her students at Parkrose High School, her family, and her community. Despite this, she has turned fear into action, by speaking out, sharing her story, and mobilizing her local community for gun reform.

Eli’s story

On the evening of December 5, 2017, Eli Saldana, a 19-year-old Native American who lives in Chicago, was just walking home when he was shot. Right before he was attacked, he noticed a man walking behind him. When he turned around to look, Saldana was hit with the butt of the gun on the left side of his temple. As he tried to run away the man fired his gun. The bullet entered Saldana’s right calf muscle but fortunately he escaped, making it home with his life.

Like Saldana, 70 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives live in urban areas19 and are thus exposed to the dangers of gun violence, like other racial minority groups. Saldana now lives with the physical scar of the bullet wound and the emotional scars of the event. However, he has used his traumatic experience to educate young people on gun violence and avoiding gang life. He’s taken up music and uses that to connect with his nieces, nephews, and other Native American youth in hopes of being a positive role model.20

Different communities, different impacts

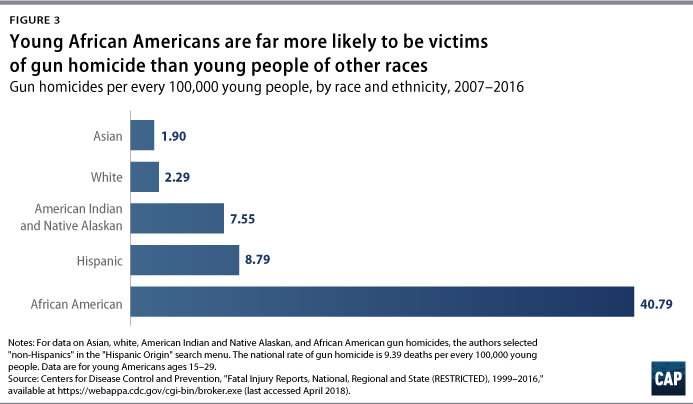

Generation Z and Millennials are the largest and most diverse generations in American history, and the burden of gun violence does not fall equally across their communities. Young African Americans, for example, face an exponentially higher risk of being the victim of a gun murder compared to young people of other races in the United States. African Americans between the ages of 15 and 29 are 18 times more likely than their white peers to be the victim of a gun homicide.21 While African Americans accounted for 15 percent of the population of young people in this age range, they comprise 64 percent of gun homicide victims.22 This dynamic is present among both men and women—young African American women, although they represent a small portion of gun-related homicides overall, are six times more likely than young white women to be the victim of a gun homicide.23 Young Hispanics also face higher rates of gun homicides, with rates that are four times higher than their white peers.24

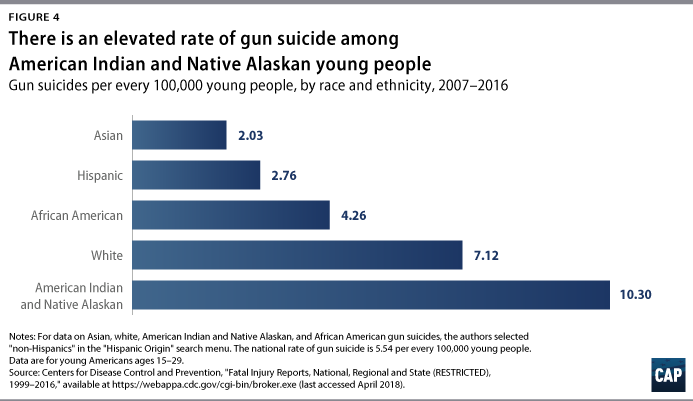

In contrast, gun suicides disproportionately impact white and Native American youth in the United States. From 2007 to 2016, the gun suicide rate among young white Americans was 2.6 times higher than Hispanics, 1.7 times higher than African Americans, and 3.5 times higher than Asian Americans.25 Similarly, young American Indians and Native Alaskans presented a rate that was 3.7, 2.4, and 5.1 times higher than the rates among Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians, respectively.26 A young Native American commits suicide with a gun every six days in the United States.27 These numbers likely do not tell the whole story, as studies have found that overall deaths for American Indian or Alaska Native populations are underreported by 30 percent.28 The elevated rate of suicide among young Native Americans presents a serious concern for tribal leaders, and as the National Congress of American Indians explained in 2015, “The higher incidence of suicide in Native peoples is informed by a long history of systemic discrimination and abuse.”29

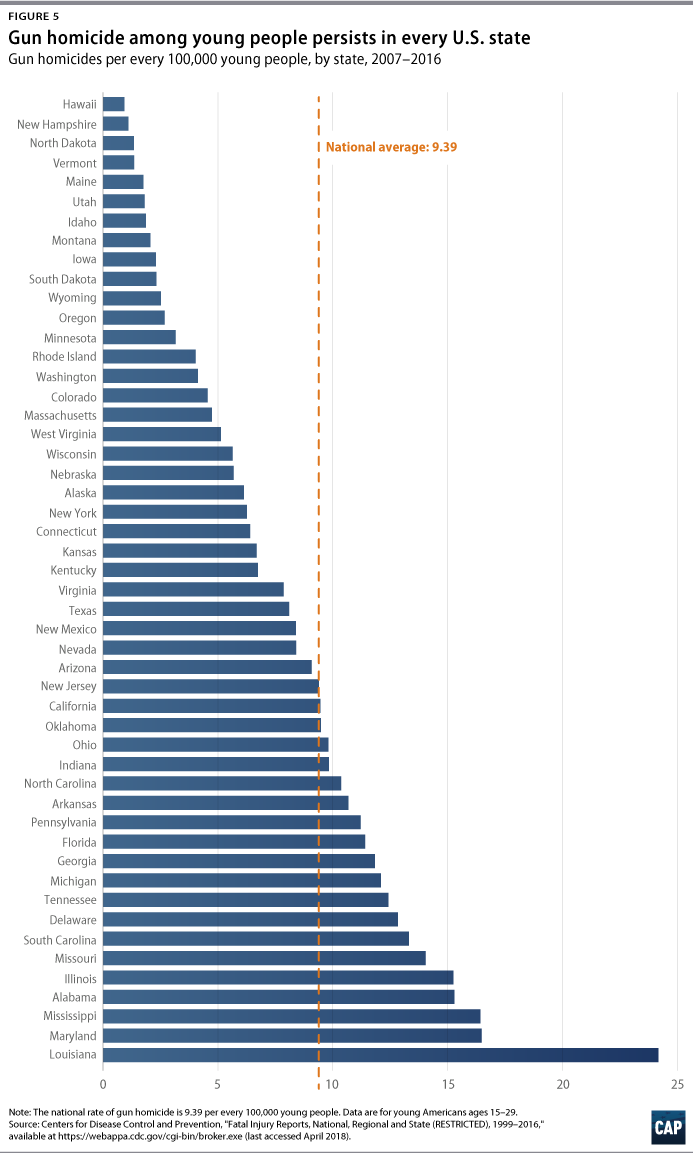

50 state breakdown: Gun homicides, suicides, and domestic violence homicides of women

The experience of gun violence among young people varies widely depending on location. While the national numbers tell a disturbing story about the extent to which young lives in the United States are taken by gunfire, the reality is that a young person’s risk of becoming a victim of gun violence depends, largely, on where they live.

While approximately 17 young people are murdered with a gun every day in the United States, this risk is not borne equally by young people across the country.30 The gun homicide rate of young people ages 15 to 29 varies dramatically from state to state. Louisiana has the highest rate of gun homicides of young people in the country, followed by Maryland, Mississippi, Alabama, and Illinois.31 The average gun homicide rate of young people in these five states is 14 times higher than the average of the five states with the lowest rates: Hawaii, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Vermont, and Maine.32 Louisiana’s rate alone is more than 2.6 times higher than the national rate and 47 percent higher than Maryland’s rate, the second-ranking state.33

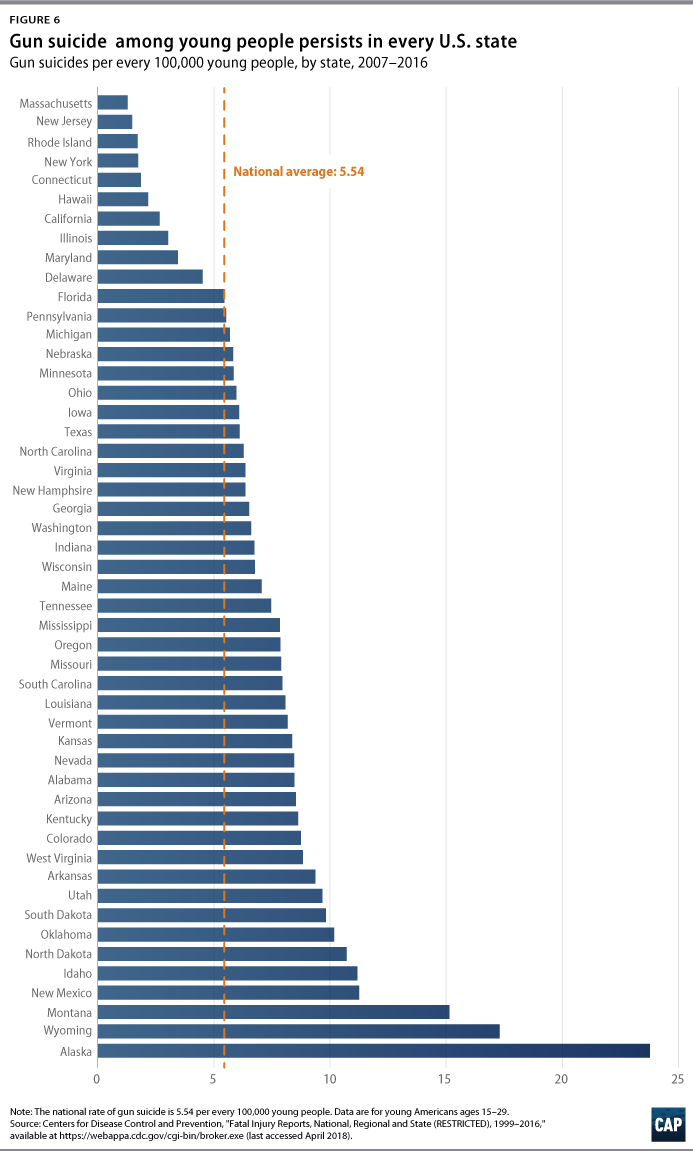

A similar discrepancy is apparent among states when it comes to gun-related suicides of young people, although with a different distribution among the states. Alaska has the highest rate of gun suicide among people ages 15 to 29, followed by Wyoming, Montana, New Mexico, and Idaho. Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island, New York, and Connecticut have the lowest rates.34 Young people in the five highest ranking states are 10 times more likely to die by gun suicide than young people in the five lowest ranking states.35

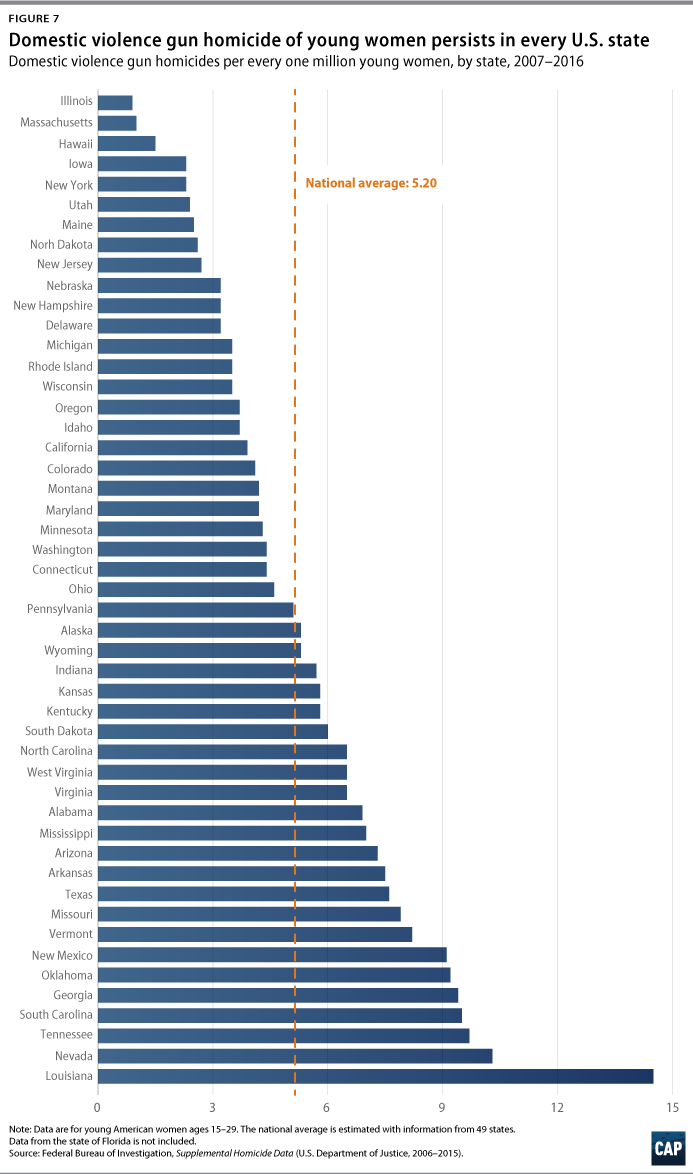

A third category of gun violence that impacts young people and in which there is a wide disparity in risk based on geography is gun homicides of women by intimate partners or family members. The risk posed by the presence of a gun in domestic violence situations is well established, particularly with respect to women of all ages.

Research has shown that the presence of a gun in a domestic violence situation increases the risk of homicides against women by 500 percent.36 Young women in abusive relationships face a substantial risk by partners or family members with access to guns. From 2006 to 2015, 36 percent of murders of young women between the ages of 15 and 29 were committed by an intimate partner or family member, and 54 percent of those murders were committed with a gun.37 Indeed, young women are more vulnerable to domestic violence gun homicides when compared to other women. From 2006 to 2015, the rate of domestic violence gun homicides of young women was 30 percent higher than for women of all ages.38 This statistic is mainly driven by violence in dating-partner relationships. From 2006 to 2015, out of the more than 1,550 young women killed with a gun in domestic violence situations, 65 percent were murdered by a dating partner.39

Mariam’s story

Mariam El-Haj, 26, grew up in south Texas in a strict, multicultural family. While she had a tense relationship with her father, nothing prepared her for what happened on June 15, 2012. Mariam was at home with her boyfriend, mother, and two sisters, when her estranged father broke into the house wielding a handgun. Angered by an ongoing divorce from his wife and enraged by his daughter having a boyfriend, El-Haj’s father unleashed a volley of bullets. El-Haj was shot two times, her mother was shot twice, and Mariam’s boyfriend was shot once. After six shots were fired, one of Mariam’s sisters was able to take the gun from her father.

Miraculously, everyone survived, but the memory lives in the family’s mind, continuing to torment them years after the incident. After her traumatic event, El-Haj decided that she wanted to use her voice so no one else would have to share her experience. She is an outspoken advocate for gun violence prevention; joined Generation Progress’ Fight4AFuture National Leadership Council; and regularly shares her powerful story in order to push for tougher restrictions on the ability of domestic abusers to acquire guns.40

Again, the risk varies widely from state to state. Louisiana, Nevada, and Tennessee have the highest rates of gun homicides of young women by intimate partners or family members, while Illinois, Massachusetts, Hawaii, and Iowa have the lowest.41

Looking across all three of these categories of gun violence, 11 states rank among the 25-worst states in all three categories for people ages 15 to 29: gun homicides, suicides, and domestic violence gun homicides of women. In contrast, 11 states are not among the 25 worst in any of these categories.

There are many factors that influence the rate of gun violence in a particular state, and attempting to parse out the precise reasons behind these rates has been a frequent subject of academic research. One factor that appears to have a significant effect is the relative strength of a state’s gun laws. A 2016 CAP study found that the 10 states with the weakest gun laws collectively had rates of gun violence that were 3.2 times higher than the 10 states with the strongest gun laws.42 Similarly, relative strength of gun laws seems to be a factor in the state-to-state variations in gun death rates among young people. Out of the 11 states that ranked among the 25 worst in all three categories, nine received an “F” by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence for the strength of their gun laws, the lowest possible score.43

Long before the student survivors at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School turned their grief into action,44 young people, especially young African Americans and Latinos, have been working to curb gun violence in their communities. Being the communities that gun violence affects the most, young people have been at the forefront in the fight to end cyclical violence, mass shootings, and suicide. Survivors and students from Virginia Tech mobilized to push for tougher gun safety measures across the United States.45 After the June 2016 massacre at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, young LGBTQ leaders stepped up to demand immediate action on gun laws.46 The groundwork these and other young activists laid contributed to the recent enactment of a package of new gun laws in Florida in March 2018.47

Young people’s activism is not limited to responding to mass shootings nor is it limited to legislative solutions. The Parkland students had a blueprint for success modeled after the work of Black Lives Matter organizers who, for years, have organized in communities across the country to pressure elected officials to fix broken systems and laws that are not serving a majority of people.48 Young black leaders in the United States have used the tools at their disposal, including personal narratives and social media, to light up a movement that, since its inception, has shifted the national conversation and resulted in positive and concrete changes to laws around the country.

Policy options to reduce gun violence

A Harvard University poll showed that almost two-thirds of Americans under 30 support stronger gun laws.49 Young people understand that legislative action is key to ending the gun violence epidemic, but they also understand that further steps must be taken. In addition to stronger gun laws, youth leaders have demanded support for community-based violence intervention programs and ensuring sufficient data and research to inform all of these efforts. While there are many dangerous gaps and weaknesses in our gun laws that demand immediate attention from lawmakers, the following six priority policies are among the most urgent and would have a significant impact on saving young lives.

- Ban assault weapons and high capacity magazines. Assault weapons and high-capacity magazines dramatically increase the lethality of shootings. For example, a review of mass shootings found that 155 percent more people were shot and 47 percent more people were killed when assault weapons or large-capacity magazines were used.50 Assault weapons and guns equipped with high capacity magazines, together, account for up to 36 percent of guns used in crime.51

- Enable the Centers for Disease Control to research gun violence as a public health issue. In 1996, Congress imposed new restrictions on the ability of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to study gun violence and drastically cut the funding available for this research. Since then, the CDC’s annual funding for this research has fallen 96 percent, leaving many gaps in our knowledge regarding gun violence.52

- Require background checks for all gun sales. Under current federal law, only gun sales conducted by a gun dealer require a background check. Sales by private sellers at gun shows, online, or anywhere else can be completed without a background check and with no questions asked.53

- Support local violence prevention and intervention programs. Community-based programs that engage all local stakeholders to address gun violence are a crucial part of reducing gun deaths. These evidence-based programs can have a significant effect. For example, from 2011 to 2016, three cities in Connecticut experienced a 50 percent decline in gun homicides thanks to the Group Violence Intervention Program.54 Similarly, between 2007 and 2016, Richmond, California, saw a 71 percent reduction in gun violence leading to injury or death due to a comprehensive strategy that addressed gun violence in the city.55

- Disarm all domestic abusers. Current federal law only prohibits some domestic abusers from buying and possessing guns, but abusers in dating relationships, those convicted of stalking, and those subject to temporary restraining orders are free to buy guns under federal law. These gaps in the law put many young women at risk. 56

- Make extreme risk protection orders available in every state. This is a tool that allows family members or law enforcement officers to request that a court temporarily remove firearms from a person who has shown signs of being a risk of harm to themselves or to others. This type of law has already shown promising results in states where it has been enacted. Researchers found that for every 10 to 20 such orders issued in Connecticut, one life was saved.57

Along with these proposals, young people understand that curbing the epidemic of gun violence requires a comprehensive gun violence reduction strategy that places the problem in context with the criminal justice system, the education system, health and housing policies, and racial and economic inequality. Community reinvestment in areas hardest hit by gun violence is just as essential to reducing gun violence as solutions that regulate firearms. Examples of these policies include:

- Youth jobs programs. Economic opportunities for young people are key to violence reduction. Programs such as the summer jobs programs in Chicago58 and Boston59 have demonstrated significant reductions in violent crime among youth from neighborhoods hard hit by gun violence.

- Reinvestment in high-quality education programs in areas suffering from gun violence. For students in areas most affected by gun violence, investing in education programs are key to achieving violence reduction. Similar to how jobs programs offer economic opportunity, high-quality educational opportunities—through funding to ensure high-quality schooling, including after-school programming,60 and education for youth in prison61—are important to curbing cyclical gun violence among young people.

- Implement trauma-informed education programs. Young people dealing with trauma, given their generation’s high-level of exposure to gun violence in the United States, must be provided support. Investing in trauma-informed education programs in schools has proved effective at increasing resiliency among children suffering from trauma62 and reducing recurring violence in communities.63

- Smart on crime approaches to criminal justice. Cities that implement local efforts to reduce unnecessary arrests and incarceration as well as promote re-entry success by removing significant barriers to opportunity for the formerly incarcerated help to make communities safer. These programs have been implemented in cities such as Philadelphia, New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles. These “second chance” cities offer an alternate path for system-involved individuals that reduces recidivism and can serve as a key part of reducing violence.64

Bruce’s story

Bruce Franks Jr., 33, a leader in Generation Progress’ Fight4AFuture gun violence prevention network, is no stranger to gun violence. Growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, he’s been exposed to gun violence from an early age. When he was just 6 years old, he saw his 9-year-old brother shot and killed in front of a neighbor’s house. In 2004, as a young man, a stray bullet struck him in the knee, ending his track career. Gun violence, however, was not the only barrier Franks faced growing up. He quickly realized how systematic racism and an unjust criminal justice system impacted his life and his community as well.

Following the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Franks became a leader in the Black Lives Matter movement during the protests in the wake of the shooting. He went on to build civic power by becoming a liaison between the community and the St. Louis Police Department. Then, in 2016, he ran and won a seat in the Missouri state legislature. As a state representative, Franks has been a leader in gun violence prevention with solutions that go beyond standard gun restrictions. He understands that community reinvestment is key to slowing the epidemic of gun violence and scored his first legislative victory last year when he secured $6 million for Missouri’s youth summer jobs program in the state’s budget. In announcing the summer jobs program Franks said, “[T]hat’s 2,700 youths off the streets, doing something productive.”65