For more information on cross-border gun trafficking, see: “Beyond Our Borders: How Weak U.S. Gun Laws Contribute to Violent Crime Abroad” by Chelsea Parsons and Eugenio Weigend Vargas

Gunfire, explosions, and chaos erupted in the Mexican city of Culiacán on October 17, 2019, as members of the Sinaloa cartel took to the streets armed with assault weapons, including high-caliber rifles, in an unabashed display of power. The cartel, enraged by the recent arrest of Ovidio Guzmán López—the son of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, a former leader of the Sinaloa cartel—terrorized communities within the city and engaged in a forceful gun battle with Mexican military forces, demanding Guzmán López’s release. The gun fight resulted in eight fatalities and multiple injuries before the Mexican federal government relented and released Guzmán López to end the bloodshed. This breakdown of the rule of law has exposed a harsh truth: Cartel members are armed with weapons capable of defeating Mexico’s military forces.

What happened in Culiacán is not an isolated case; similar confrontations have occurred in other Mexican cities and states. In 2011, for example, cartel members used AK-47 rifles to hold a three-day battle with military and police forces in the state of Tamaulipas. And during a gun battle in 2016, cartel members used a Barrett .50-caliber rifle to take down a state government helicopter in the state of Michoacán, killing four passengers. These incidents of cartels using arsenals of military-grade weapons in defiance of the Mexican government beg the question: Where did these guns come from?

The state of Mexico’s gun laws

Mexico has strict gun laws, so these guns are not legally coming from within the country. There is only one gun store in Mexico, with regulations designating certain caliber firearms exclusively for military use as well as specific, restrictive requirements for private ownership of firearms. Theoretically, the gun laws in Mexico should restrict access to firearms, especially military-style semi-automatic assault weapons. In reality, however, Mexico’s gun laws are severely undermined by an internal environment that breeds corruption and an external environment that enables gun trafficking.

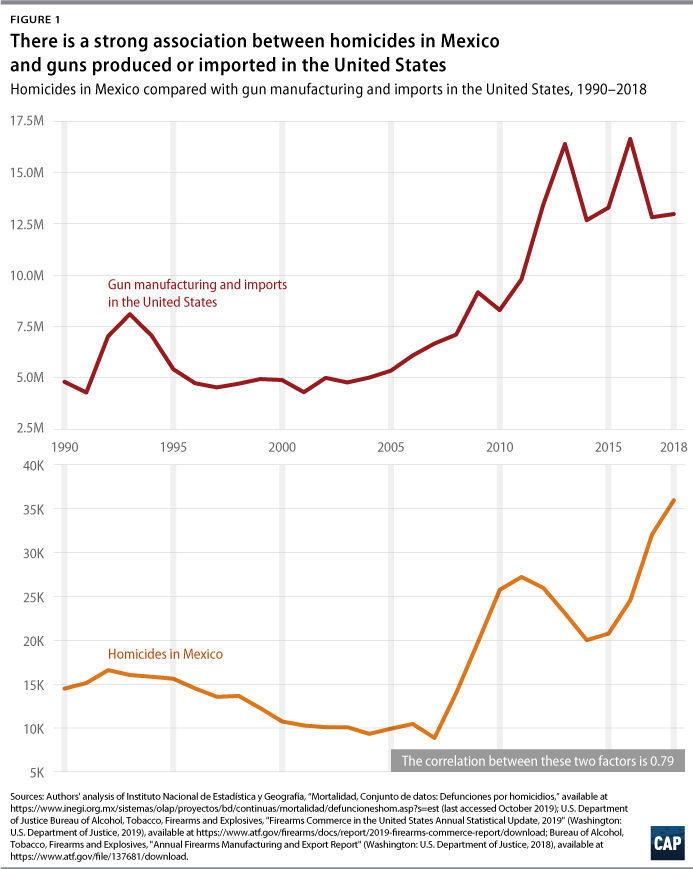

Mexico’s gun laws have not changed since the 1970s and, until relatively recently, were accompanied by declining rates of violent crime, including homicide. However, the trend shifted sharply in the mid-2000s, with a dramatic rise in homicides despite no changes to Mexico’s gun laws. What did change in the mid-2000s were two related developments in the United States: a significant increase in the manufacturing and importation of guns within the country and the expiration of a key U.S. gun law.

A major shift in U.S. gun policy, manufacturing, and imports

While high correlation does not necessarily imply causation, other factors indicate that these two issues are more than a statistical coincidence. (see Figure 1) Gun manufacturing in the United States, which had been declining from 1996 through 2004, didn’t only begin increasing production numbers from 2005 onward; it grew specifically in the market of rifles and higher-caliber pistols—weapons of choice for Mexican cartel members. The Mexican states most affected by the subsequent sudden spike in violence were those closest to the United States. While the six Mexican border states reported 14 percent of total homicides committed in the nation from 1990 to 2006, that number rose to close to 30 percent of all homicides committed in Mexico from 2007 to 2018.

In addition to the growing levels of firearm production and importation in the United States, there was also a drastic change in federal U.S. gun laws in the mid-2000s, with the 10-year federal assault weapons ban expiring in 2004. The ban, which barred the manufacture, import, sale, or transfer of assault weapons, was an effective mechanism to decrease gun violence in the United States, with evidence that it had reduced mass shootings by 25 percent and mass shooting deaths by 40 percent. Its expiration led to devastating repercussions in the United States, with evidence indicating a 347 percent increase in mass shooting deaths in the decade after the ban expired. Similar effects spread to Mexico. A 2013 study found that after the federal assault weapons ban was lifted in 2004, gun homicide rates rose in the Mexican municipalities bordering the United States—with the exception of those that border California, which has a state-level ban on assault weapons.

Further compounding the argument that Mexico’s gun violence problem stems from across its northern border is the reality that the United States is a primary source of guns for Mexico. While firearms are trafficked to Mexico from a variety of countries, guns from the United States account for 70 percent of the guns recovered and traced from crimes in Mexico. One study estimated that, from 2010 through 2012, close to 213,000 firearms were purchased annually in the United States with the goal of trafficking them to Mexico. In fact, according to data from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, the United States has consistently been the source country for the vast majority of guns recovered in crimes in Mexico since 2009.

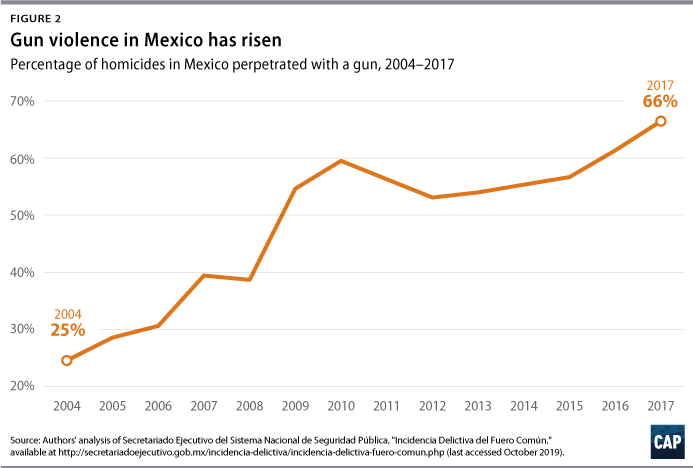

The flow of guns from the United States into Mexico has had devastating consequences for Mexican communities. In addition to confrontations between cartel members and military officers, gun homicides have significantly increased. While gun homicides in Mexico represented 25 percent of total homicides in 2004, this figure rose to 66 percent by 2017. Meanwhile, femicides perpetrated with a gun, gun robberies, and the number of people injured in shootings have all risen as the rates of gun violence continue to surge.

The epidemic of gun violence and the proliferation of cartels in Mexico have created an untenable environment in many parts of the nation, requiring clear and swift action by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to address corruption and restore the rule of law. However, this problem cannot be resolved solely by action from the Mexican government; it is imperative to address the United States’ complicity in fueling this violence as well.

Conclusion: Acknowledgement of a shared problem

One cannot ignore the reality that the violence in Mexico is perpetrated by U.S. guns. Immediately following the gun battle in Sinaloa, officials from both countries engaged in a dialogue announcing Operation Frozen, which seeks to reduce gun trafficking on five major crossing points in the U.S.-Mexico border. While the specifics of this operation are currently unknown, the recognition of a shared problem is important. Still, more needs to be done internally within the United States to effectively quash the flow of firearms into Mexico. For example, a federal ban on assault weapons would stop the new manufacture, import, sale, and transfer of the class of weapons most desired by cartels. Implementing universal background checks that require all buyers of firearms to pass a background check, regardless of whether the seller is a gun dealer or a private seller, would make it harder for cartels to purchase guns and transfer them across the border. Stricter inspection and regulation of gun stores in the United States to ensure that they are not targeted by gun trafficking rings would block cartel supply streams.

These commonsense policies have a dual benefit for U.S. legislators: If adopted, they would not only prevent gun trafficking and reduce the devastating damage done by cartels in Mexico but also reduce gun violence within the United States. Communities on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border are bleeding out, devastated by gun violence fueled by U.S. guns. The violence is preventable, and it is stoppable. It’s time for elected leaders, within both the United States and Mexico, to act.

Eugenio Weigend Vargas is the associate director for Gun Violence Prevention at the Center for American Progress. Rukmani Bhatia is the policy analyst for Gun Violence Prevention at the Center.