Introduction and summary

When the Camp Fire burned through Paradise, California, in November 2018, 85 people lost their lives and more than 18,000 structures were destroyed.1 Stories from Paradise make clear that the impacts of the fire were not equally borne across the community. Newer homes were more likely to be spared because they were built to more stringent safety codes, while older homes were more likely to burn.2 The people unable to escape the deadly fire were disproportionately elderly or disabled.3 And in the fire’s aftermath, many residents have been faced with housing shortages, insurance challenges, and crumbling infrastructure that have kept them in limbo and had an outsized impact on their lives.4

This pattern is seen elsewhere in the United States after fires, floods, and hurricanes: The obstacles facing disadvantaged communities are compounded during and after a disaster. As climate change makes wildfire seasons longer, hotter, and drier, it is important to examine the disproportionate impacts seen across communities as well as the potential tools that state and federal governments can use to mitigate those impacts.5

Recent research has found that 12 million Americans living in areas where wildfires are common are unable to prepare for or recover from a potential fire. In short, an event like the Camp Fire would be devastating.6 And African American, Latino, and Native American communities are disproportionately likely to be vulnerable.

As the Camp Fire demonstrated, vulnerable populations are too often left behind when it comes to planning for and recovering from catastrophic wildfires. Federal, state, and local policies, programs, and funding must acknowledge and strive to address this inequity. U.S. disaster response and recovery policies should be commensurate with the scale of the threat and cannot leave behind the most vulnerable communities. Policymakers must ensure that resources are available to all communities—regardless of wealth and power—so that they can plan and take actions to reduce the threat of wildfires to lives and homes and enable recovery if a wildfire does occur.

To that end, this issue brief discusses how to ensure equal access to disaster response and recovery efforts, offering specific policy recommendations that would help ensure that the most vulnerable communities and populations receive the support they need.

Ensuring equal access to disaster response and recovery

Wildfires are a natural event in the wildlands of the United States, especially in the West and Southeast. Residents have to accept them as part of the landscape, despite the threats they pose. This is why it is important to ensure that communities are resilient when it comes to wildfires and establish that they have the capacity to function at some level after a wildfire, allowing them to recover within weeks or months. In the absence of this resilience, natural events can be catastrophic, and communities may require years to restore limited functionality to critically important systems. While any disaster is bad in the short term, long-term catastrophes are unacceptable.

That certain groups are unequally vulnerable to wildfire becomes clear in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. Elderly individuals, for example, made up a majority of the fatalities in the Camp Fire.7 And evidence suggests that particular groups—low-income people, people of color, and renters—are much less likely to rebuild after a fire than others. These groups are also less likely to access resources that would help with recovery.8

The challenges of recovering from wildfires are evident at the community level as well, especially for communities with limited resources. In Paradise, the path to rebuilding remains unclear a year after the Camp Fire. Even the town’s water system has been compromised and may require hundreds of millions of dollars to replace.9 This is a major investment for a city and county that had a limited tax base even prior to the disaster and is made even more difficult now that over 90 percent of the town’s population has moved away.10 Despite this lack of resources, many homeowners have returned to the homes that survived the fire, as insurers have deemed them habitable. Unfortunately, the loss of municipal water supplies does not affect insurer decisions.11 These families are forced to store water on-site, even though the various businesses and services they relied on are still unable to rebuild.

Calaveras County, California, and Weed, California, provide other examples of how recovery alters the characteristics of a community. In the former, small mountain communities continue to debate how to move forward and redevelop a local economy after a wildfire that occurred in 2015.12 In the latter, after a late 2014 wildfire, the rebuilding process has been constrained by contractor availability in a town of 3,000. This challenge may well worsen as time passes and demand for contractors increases in nearby cities such as Redding and Paradise, which need new homes after their own fires.13

There is a clear need to ensure that all communities and groups have the resources to protect themselves during a wildfire as well as adequate support to recover after a fire.

Protecting people during wildfire

Past disasters, whether wildfires, hurricanes, or earthquakes, have shown that at-risk populations—including low-income, elderly, and disabled people—are at a disadvantage when it comes to preparing for and experiencing a disaster. At-risk populations often have limited resources to dedicate to preparation, and emergency services often miss them during events because of challenges such as limited capacity or language constraints.14 After Hurricane Katrina, researchers found that flooding and storm damage disproportionately affected low-income communities, which were disproportionately African American.15

Language barriers also present challenges during emergencies, as they make it difficult for agencies and first responders to share information with all community members in the path of a wildfire.16 Moreover, evacuations from Paradise, which had a limited number of exit routes, highlight the importance of clearly designating sheltering areas and the strategic locations of buses and other vehicles that can take people to safety during an emergency. This is especially true for seniors, disabled individuals, and those without vehicles.

Targeted universalism

Policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels need to ensure that communities have the resources they need to respond to a catastrophic wildfire. In general, they need to ensure that resources are accessible, equitable, and effective for all communities—particularly, at-risk populations such as aging, homeless, carless, or disabled individuals. There are a range of policies and programs that might be effective in a given locale. Rather than list all of them, CAP proposes that federal and state agencies review disaster response programs to ensure that they satisfy the principles of targeted universalism—an approach meant to ensure that programs are designed to accommodate the challenges that specific groups are likely to encounter in accessing them, thus making programs accessible to all.17

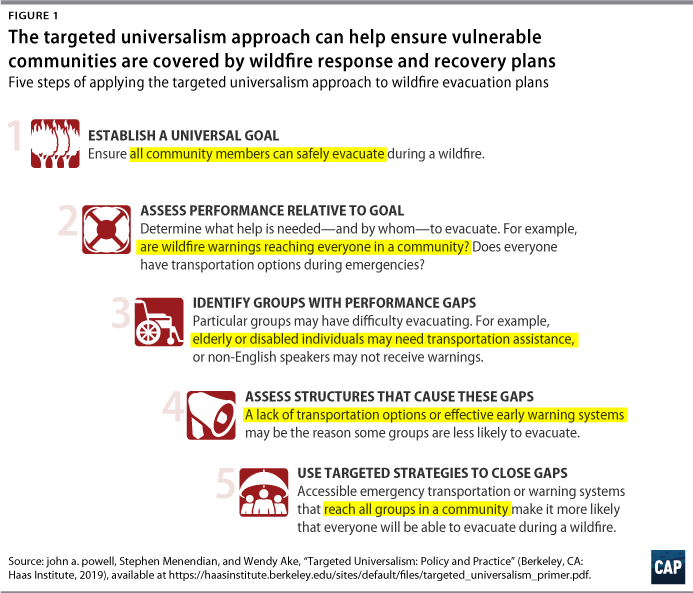

The targeted universalism framework lays out general steps to plan a program that achieves universality in an effective way. It begins with establishing a universal goal: For example, ensuring that all members of a community can safely evacuate during a wildfire. (see Figure 1) This is followed by assessing community performance relative to that goal and using that assessment to determine which groups are likely to have challenges meeting the goal. This insight provides guidance for evaluating why certain groups experience difficulty achieving the goal and using this understanding to implement strategies that ensure each group is able to reach the goal.

The city government of Austin, Texas, has used targeted universalism to plan the expansion of its parks system.18 The city council set a goal that all residents live within half a mile of a park. The city evaluated gaps in the current system, looking at different groups within the city to determine where access to parks was limited—and what the needs of different groups were—in order to acquire new parkland and ensure that every community member would have access to these public open spaces. Knowledge of these gaps has helped the city acquire 800 acres of land in order to develop 20 new parks.

Helping communities rebuild equitably

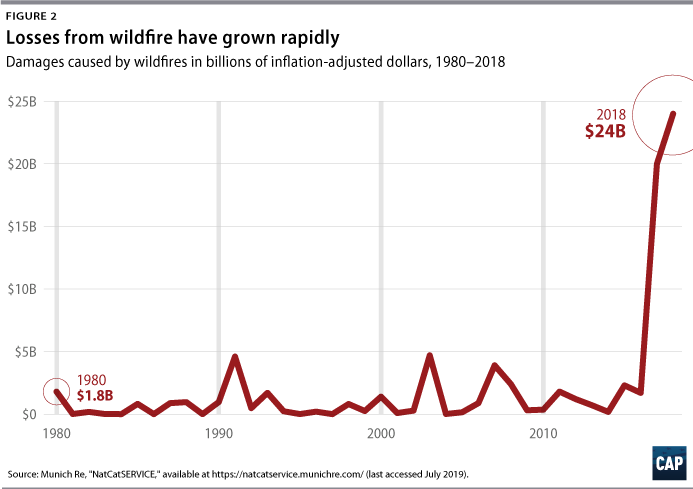

Recovering from a wildfire can take years, and it inevitably changes the shape of a community. Some people rebuild homes, while others leave the area. But these decisions are not random. In fact, they are often related to socio-economic and demographic factors. Low-income households, for example, find it harder to pull together the money to rebuild or access disaster relief services.19 This is relevant to rebuilding as well as to broader issues such as the racial wealth gap, as home ownership is especially important to overall wealth.20 Renters are faced with housing shortages and left vulnerable to price gouging.21 And in some service industries, such as outdoor recreation and tourism, employees face uncertainty if visitation drops off following a wildfire and businesses need to close or cut staff. As the toll of wildfire disasters continues to climb, it is critically important to understand how community members and business respond to these disasters. (see Figure 2)

It is difficult to generalize the rebuilding process after a wildfire. Broadly, however, policies should be framed around several objectives that incorporate the needs of all groups within a community to promote equitable recovery and a more resilient future. Recovery programs should consider how to ensure equitable access to financial resources for rebuilding, and they should monitor program participation to improve targeting and education for groups that typically underutilize these tools. If services, such as water and sanitation, have been lost, they should be prioritized in rebuilding and resilience efforts, with universal access as the ultimate goal. Affordable housing should also be central to rebuilding efforts. And community members should be included in recovery efforts to ensure that investments are in line with the needs and preferences of the community.

Policy recommendations

To better protect people during disasters and help communities recover in an equitable manner, the Center for American Progress recommends the following policies:

- Disaster response planning should include at-risk populations in a meaningful way. Any disaster response plans must include the public, particularly at-risk groups such as aging, homeless, carless, or disabled populations, in a meaningful way. Court cases have made it clear that the disaster planning of many cities has not satisfied the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).22 Although emergency alert systems are a powerful warning tool, many communities have not been authorized to communicate warnings directly to cellphones.23 Even where these systems exist, they are rarely tested. Where federal funding is used to support planning, inclusion of these groups should be required, and federal and state agencies should prepare best practices to help counties and communities develop their plans.

- Federal and state agencies should allocate greater disaster response resources to training local jurisdictions on reimbursement and cost-sharing programs to help at-risk populations. Grant programs, such as the U.S. Department of Transportation’s 5310 funds and traditional ADA programs, are available to help communities of all sizes create transportation systems that accommodate seniors and individuals with disabilities.24 These funds, and additional targeted resources, should be made available to help more communities prepare for transportation, evacuation, and sheltering during and after wildfires.

- Disaster response policies should be implemented at the statewide or regional level to prepare for wildfire at the appropriate scale. Wildfires do not respect jurisdictional boundaries. Therefore, states should ensure their municipalities and counties within the wildland-urban interface (WUI) have formalized agreements—such as continuity plans, a memorandum of understanding, and other agreements—that lay the groundwork for coordinated responses. Rural counties often have such plans for volunteer fire departments. Given the trend that wildfires are affecting more populated areas, suburban and urban agencies should institute similar plans.25

- Reform disaster relief housing programs to accommodate renters and at-risk populations. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Relief (CDBG-DR) program is the largest resource for state and local governments to fund community development after a disaster. Congress should consider recent proposals that aim to improve the program to better accommodate vulnerable communities, including one-to-one replacement of federally subsidized affordable housing after disasters and funding allocations that are accessible to renters and people experiencing homelessness to ensure that homeowners are not the only group that receives recovery support.

- Monitor recovery in communities affected by wildfire. The federal government should monitor recovery efforts in communities that have experienced a wildfire, either through the U.S. Bureau of the Census or through a grant program administered by the National Science Foundation. This research should unify disparate data sources about population numbers with anonymized socio-economic data and tax information on returning and new businesses to understand how communities rebuild in the aftermath of a fire. While being mindful of privacy concerns, these observations should be made publicly available to help states and counties understand the long-term consequences of wildfires and the effectiveness of different recovery strategies.

Conclusion

Even as greater attention is paid to the need to invest in preparedness, wildfires are almost certain to affect more communities in the coming years. If catastrophic events like what occurred during and after the Camp Fire are to be avoided in the future, agencies will need to make disaster response preparations that provide the right resources to all community members, including at-risk populations. And after a disaster, federal, state, and local agencies need to be prepared to help all community members regain access to the services and resources they need to rebuild.

About the author

Ryan Richards is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Valerie Novack, Rejane Frederick, Michael Madowitz, Azza Altiraifi, Cathleen Kelly, Guillermo Ortiz, and Connor Maxwell for their contributions to this report.