See also: “Where the Trump Budget Cuts Hit Coal Communities and Workers” by Luke Bassett

This issue brief contains corrections.

The U.S. coal industry has undergone significant changes in the past several decades. In recent years, these changes have accelerated due to transformations in the U.S. and international energy economy. They have left many coal communities in the lurch, particularly those dependent on labor-intensive underground mining in Appalachia.

President Donald Trump campaigned on promises to revitalize the U.S. coal industry and bring back coal mining jobs. On March 28, he signed an executive order that began the process of rolling back key federal efforts, including the Environmental Protection Agency’s, or EPA’s, Clean Power Plan to reduce carbon pollution from the U.S. power sector.1 Despite the rhetoric and political theater that accompanied the order’s release, it will likely have minimal impact on the coal industry and coal mining jobs, given the structural economic challenges the industry faces.

By contrast, President Trump’s fiscal year 2018 budget blueprint would have unequivocally negative impacts on communities that have struggled economically due to the coal industry’s downturn. The budget would gut the federal economic and workforce development programs that are most targeted and active in their support of these communities. It proposes eliminating all federal discretionary funding—the entirety—of 7 of the 12 federal programs that coordinate investments and other forms of assistance to support coal communities. During the last two years, these programs have worked under the aegis of the Obama administration’s Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization, or POWER, Initiative to grow new businesses and industries, create jobs, and train dislocated coal economy workers for in-demand occupations.

Based on the limited information provided by the blueprint, President Trump’s FY 2018 budget would cut at least $1.13 billion from these programs and offices, including several in their entirety—a total that may increase when the full budget is released in May.2 Through the POWER Initiative, offices and programs targeted by the cuts funded more than $115.8 million in economic development, job training, and other grant projects targeting coal communities in more than 20 states from 2015 through early 2017.3

If passed by Congress, these cuts would cripple the federal government’s ability to invest directly in coal communities and workers. They would prevent the government from helping these communities regain their economic footing and chart a viable future, one that does not rely on unfounded fantasies of the coal industry’s resurgence.4

This issue brief looks first at the history and current state of the coal industry. It then discusses why President Trump’s actions would not restore coal country—and how they threaten current federal efforts to aid coal communities in transition by investing in their economic and workforce development.

Coal mining employment loss is a long-term and largely market-driven trend

The loss of coal mining jobs is an almost centurylong story. Employment in the coal industry peaked in the 1920s and has declined more or less steadily since then. After a brief uptick in the 1970s following the OPEC oil embargo, coal employment has continued its downward slide.5 Since the 1990s, surface mining has outpaced underground mining, as the former is more mechanized and less labor-intensive, and the focal point of production has moved west from Appalachia to the Powder River and Illinois basins.6 Correspondingly, coal miner or coal mine operator employment decreased while coal production increased, most strikingly through the 1990s and 2000s. Between 1983 and 2014, coal employment dropped by 59 percent, while coal production increased by 28 percent.7 Through 2016, both coal production and employment fell, driven by market factors such as lower electricity demand.8 (see Figure 1)

Coinciding with record-low prices for natural gas and other factors—discussed below—coal mining job loss has accelerated since 2012. This loss has been especially precipitous in central Appalachia, resulting in economic devastation in already struggling communities across eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia, and southwestern Virginia. During the past five years, central Appalachia coal mining employment has declined significantly more quickly than in other regions of the country, falling from 29,616 jobs in 2012 to 12,699 jobs in 2016, a 57 percent drop.9 Over the same time period, coal mining employment in the rest of the country declined as well, by 42 percent.10

Coal industry job loss—particularly, but not exclusively, in Appalachia—can be traced to multiple factors:

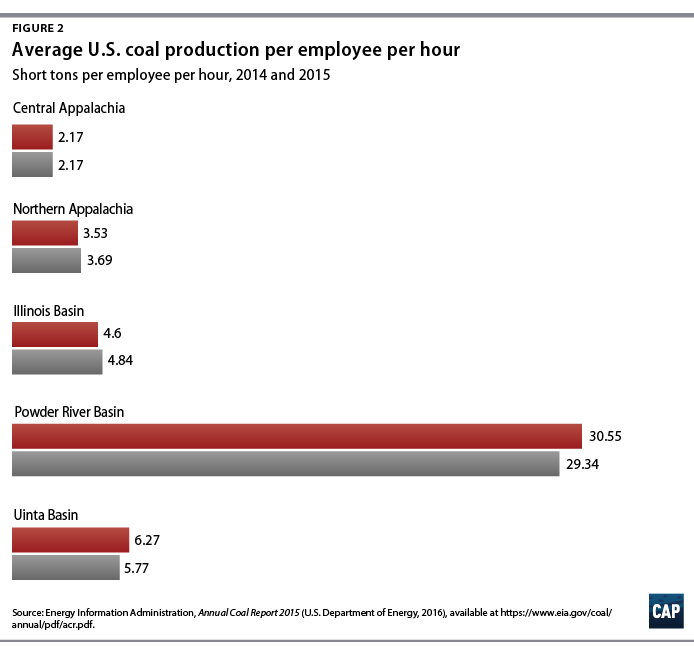

- A disparity in productivity per coal mine employee between Appalachia and coal basins in the Midwestern and Western United States due to increased mechanization used in surface mining and the thicker coal seams in the latter locations. (see Figure 2)

- A corresponding competitive disadvantage between coal mined in Appalachia and coal mined in the Powder River and Illinois basins, which has lower prices. (see Figure 3)

- Lower exports of metallurgical, or met, coal to China for use in steelmaking, diminishing an additional revenue stream for the coal industry.11 A convincing argument has been made that decline in Chinese demand for met coal—due to the country’s slowing economic growth and a move away from industrial production that depends on coal use—and resulting lower prices are the principal drivers of the decline in coal operator revenue in recent years.12

- A steep reduction in the prices of solar and wind for energy production, as well as greater use of energy efficiency and demand response measures, such as real-time pricing of electricity use.13

- An unprecedented drop in the price of natural gas. Since 2009, the price of natural gas delivered to the power sector has declined by 39 percent. In 2016, natural gas overtook coal for the first time to provide the largest share of electricity in the United States on an annual basis.14

- Pollution standards to protect air and water quality. For too long, the coal industry had a free pass to pollute. In 2011, under the requirements of the Clean Air Act, the EPA set the first limits on power plant emissions of toxic mercury, which can harm the neurological development of children.15 Federal agencies also have issued standards to protect rivers and streams from coal mining waste and limit carbon pollution from power plants, but these were finalized well after the most recent wave of coal mining layoffs in central Appalachia.

Industry representatives, academics, and market experts—as well as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), albeit only since President Trump was elected—have recognized that the difficulties facing the coal industry are primarily economic; they also recognize that lost coal employment is largely the result of business decisions the private sector made in response to these difficulties.16 The confluence of market, policy, consumer choice, and other factors reshaping the U.S. coal industry makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for policymakers to revive it in any particular region, let alone across the entire country. The U.S. Energy Information Administration recently projected a slight increase in domestic coal production through 2018 due to a corollary projected increase in natural gas prices, but that increased production would occur in western coal mining regions, not the Appalachian Basin, for reasons discussed above.17

Trump’s promises cannot stop the market forces behind coal’s decline

Whether in defiance or in willful ignorance of energy market realities, President Trump campaigned throughout 2016 on the promise of a resurgent coal industry, pledging “to bring the coal industry back 100 percent” and befriending top coal industry executives.18 The messaging resonated, and the map of Election Day results illustrates how that support played out in Appalachia and beyond.19 Since taking office, President Trump has continued to make these promises, and his early actions have revealed his close ties to the coal industry, as well as his willingness to undercut protections for public health, clean air, and clean water.20

Having promised “to stop the regulations that threaten the future and livelihood of our great coal miners,” President Trump filled Cabinet positions at the U.S. Department of the Interior, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the EPA with coal proponents.21 He has signed bills overturning rules that protect streams from toxic waste from coal mines and that help prevent mining companies from bribing foreign governments.22 On March 28, President Trump signed an executive order instructing the EPA to begin the process of rolling back the Clean Power Plan, which set the first carbon pollution standards for existing power plants and incentivized a transition to cleaner sources of energy. Upon signing the order, he stated that it will help miners go “back to work.”23 But while his executive actions make it easier for coal and power companies to pollute, they will not change the market realities that challenge the coal industry.

In fact, much of the immediate response to President Trump’s order has illustrated the stark contrast between his rhetoric, the likely outcomes of his actions, and the harsh realities for coal production in today’s energy markets. Even coal executives, including Trump campaign donor and Murray Energy Corporation CEO Robert Murray, have indicated that coal mining jobs are unlikely to return.24 Similarly, in a television interview immediately after the executive order was signed, Nick Akins—the CEO and president of American Electric Power, one of the nation’s largest electric utilities—pointed to competition from natural gas and renewable energy generation, grid management, and customer and shareholder interest in clean energy as critical factors determining the investments and business models of electric utilities going forward.25 Other challenges include the entry of new automated technologies into the mining industry.26 In addition, the order’s removal of the Department of the Interior’s 2015 moratorium on the issuance of new federal coal leases only affects mining in the West, the main competition for Appalachian coal mines, and will allow Western-based coal operators to continue to secure taxpayer-subsidized leases for future mining operations, thereby increasing their competitive advantage over Appalachian coal operators.27

Perhaps most importantly, President Trump’s executive order will do nothing to address coal communities’ urgent need for public and private investment to develop and diversify their economies, provide education and training opportunities for their workers, and address the legacy costs of coal mining on their people and places.

Obama started new efforts to revitalize U.S. coal communities

In 2015, in response to the economic crisis faced by communities and workers reliant on the coal economy, then-President Barack Obama launched the Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization, or POWER, Initiative. This coordinated effort reached across 12 federal offices in 10 agencies to align, scale up, and target federal economic and workforce funding and other resources to coal communities and coal economy workers.28

POWER defined the coal economy broadly, including communities associated with coal mining; coal-fired power plants; and related manufacturing, transportation, and logistics supply chain activities. The agencies involved in POWER worked collaboratively with key stakeholders in coal communities, including local governments, businesses and labor unions, planning and economic development organizations, workforce and job training providers, and community-based foundations. Together, federal agencies and local stakeholders identified and funded projects across various industry sectors that hold the promise of building a more economically diverse and resilient future for these communities. A foundational premise of POWER was the belief that successful economic development results from focusing on regional economic ecosystems and bottom-up strategies that leverage local and regional assets to the fullest.

The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration coordinated the POWER Initiative and was one of the agencies that issued competitive funding opportunities as a part of it.29 Other federal agencies and offices included:

- The Appalachian Regional Commission, or ARC: Established in 1965 to invest in economic and workforce opportunities, critical infrastructure, and other assets in Appalachia, the ARC also awarded direct funding to projects through POWER30

- The Employment and Training Administration, or ETA, National Dislocated Worker Grants program: Part of the Department of Labor, the ETA awarded dislocated worker grants to state workforce development agencies that provide employment and training services to workers in communities experiencing layoffs related to downturns in the coal economy31

- The Rural Business-Cooperative Service, or RBS, Rural Economic Development Loan and Grant program: Part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, RBS’ loan and grant programs added priority consideration for coal community applicants to start and grow new businesses and conducted focused outreach to coal communities32

- The Community Development Financial Institutions, or CDFI, Fund: The CDFI Fund—part of the U.S. Department of the Treasury—included investment in coal communities affected by job losses as a targeted investment option in the 2016 New Markets Tax Credit Program for investors focusing on distressed communities33

- The Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, or OSMRE: Part of the Department of the Interior, the OSMRE identifies and leverages links between abandoned mine land, or AML, coal mine reclamation projects and local economic development strategies, as part of a pilot program34 (see below)

The remaining federal partner agencies and programs included the U.S. Department of Energy, the Department of Commerce’s SelectUSA and National Institute of Standards and Technology Manufacturing Extension Partnership programs, the Corporation for National and Community Service, the Small Business Administration’s Regional Innovation Cluster program, and the EPA’s Brownfields Program.35

To support these efforts and to make significant additional investments in coal communities, workers, and coal technology innovation, President Obama included the POWER+ Plan in his FY 2016 and FY 2017 budgets.36 This plan requested funding for economic and workforce development programs as part of the POWER Initiative (see Table 1) and $1 billion in funding from the AML reserve for efforts linking abandoned coal mine reclamation and economic development. It also required the transfer of federal funds to protect pension and health benefits for retired coal miners and their families, as well as two new tax credits to incentivize deployment of carbon capture technologies at new and existing power plants and the permanent storage of carbon dioxide from these sources.37

Congress failed to pass bipartisan legislation consistent with the biggest funding proposals of the POWER+ Plan. Senate Majority Leader McConnell blocked the Miners Protection Act from being included in successive omnibus spending bills, despite the fact that the legislation would have fulfilled the federal government’s long-standing commitment to backstop health and pension benefits for retired coal miners and their dependents, thousands of whom are Kentucky residents.38 In the House, Rep. Hal Rogers (R-KY) introduced the Revitalizing the Economy of Coal Communities by Leveraging Local Activities and Investing More, or RECLAIM, Act, which mirrored President Obama’s proposal to invest in AML cleanup projects tied to economic development strategies.39 It gained bipartisan support and considerable attention from coal country but did not advance.

See Also

Congress did, however, appropriate funding for many of the economic and workforce development increases requested in the POWER+ Plan. In fact, most of the awarded POWER Initiative projects were funded by appropriations specifically for targeting federal investment to economically distressed coal communities and dislocated coal economy workers. From its inception through March 2017, the POWER Initiative awarded nearly $115.8 million to projects in coal communities across the country, including projects with broad regional impacts.40 In addition, Congress appropriated $90 million in 2015 to the three states with the highest numbers of unreclaimed AML sites—Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia—to serve as a pilot for the POWER+ AML economic revitalization proposal.41*

The POWER Initiative grants and awards have enabled more than 120 organizations—from state governments to nonprofit organizations—to create, enlarge, or otherwise improve programs that benefit coal miners and their communities in more than 20 states.** The Center for American Progress analyzed the impact of these awards and found that counties benefiting from the POWER Initiative overwhelmingly supported President Trump in the 2016 election.42

Trump’s budget undoes this progress and breaks his promises to coal miners and their communities

On March 16, 2017, the Trump administration released its FY 2018 budget blueprint, which provides a broad outline of the administration’s funding priorities.43 In explaining how decisions were made about proposed spending cuts across the entire federal budget, Mick Mulvaney, the director of the Office of Management and Budget, said, “When you start looking at places that we reduce spending, one of the questions we asked was, can we really continue to ask a coal miner in West Virginia … to pay for these programs?”44 Given that explanation and President Trump’s professed support for coal country and coal miners, it is startling and contradictory that the budget blueprint—although it does not provide details on all relevant budget line items —defunds the very programs that are most actively helping economically struggling communities and workers in coal country.

As shown in Table 1, the Trump budget proposal would eliminate $1.13 billion in funding for seven federal programs and/or offices, in part or in entirety, that provide direct, economic, and workforce development assistance and other services to coal miners and their communities.45 The Trump budget blueprint does not expressly eliminate the other five federal offices in the POWER Initiative, but top-line funding levels specify additional cuts and, where not specified, suggest almost certain cuts when the full budget is released. For example, the 5.6 percent cut estimated across the Department of Energy may apply to the energy jobs and workforce development activities that contributed to the POWER Initiative.46 The cuts definitely include non-POWER Initiative programs that aid coal country, such as the Weatherization Assistance Program, which saves low-income families—a disproportionate number of whom live in coal country—an average of $283 per year on home energy costs.47 The budget’s rollback of the POWER Initiative programs would stunt economic revitalization where it is needed, and additional cuts to other assistance programs would compound the economic challenges facing coal communities and the families who call them home.

Conclusion

There is no canary in the coal mine to warn against the unfounded promises President Trump has made on the campaign trail or in office. Market forces have shifted coal production and employment away from Appalachia, and President Trump’s budget would cut vital funding aimed at revitalizing these coal communities and helping them move into the future. Without facing reality and continuing to invest in actual pathways that would lead to coal country’s economic development and diversification, the president will leave those communities and workers even further behind.

Luke H. Bassett is the Associate Director of Domestic Energy Policy at the Center for American Progress. Jason Walsh is the National Policy Director at The Dream Corps. He was a senior policy adviser in the White House under President Obama, where he helped design and coordinate the POWER+ Plan and the POWER Initiative.

*Correction, April 24, 2017: This sentence has been corrected to state that Congress appropriated $90 million in 2015 to the three states with the highest numbers of unreclaimed AML sites.

**Correction, April 24, 2017: This sentence has been corrected to state that the POWER Initiative grants and awards have enabled efforts of more than 120 organizations.

***Correction, April 24, 2017: This table has been corrected to state that the Department of the Interior’s FY 2017 request was “None.”