One of the most visible and immediate ways climate change has affected—and will continue to affect—Americans is through extreme weather exacerbated by rising global temperatures. Between 2005 and 2015, the annual average temperature in the United States exceeded the 20th-century average every year, with increases ranging from 0.15 degrees Celsius to 1.81 degrees Celsius above normal. Moreover, the federal government’s most recent National Climate Assessment concludes that as temperatures continue to rise, extreme weather events and wildfires will increase in frequency and intensity. Climate change will worsen heat waves, winter storms, and hurricanes. It will exacerbate extremes in precipitation, leading to more severe droughts and wildfires in some areas and heavier rainfall and flooding in others. And when the damage is done, taxpayers will be left to pick up the bill.

Extreme weather events and wildfires not only pose real threats to human health and safety—they put taxpayers at risk as well. Between 2005 and 2015, 93 natural disasters in the United States caused more than $1 billion in damage each, amounting to $586 billion in total losses. This damage can profoundly affect state and local economies. Even after a storm passes or a wildfire is extinguished, displaced people and shuttered businesses impose ongoing financial burdens on communities. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, for example, found that New Orleans lost 95,000 jobs and an estimated $2.9 billion in wages during the first 10 months after Hurricane Katrina.

When extreme weather strikes and state and local governments are overwhelmed, the federal government must often intervene. In the worst cases, the president can declare an emergency or a major disaster, which releases federal funds for the damaged areas. The Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, provides financial assistance to local, tribal, and state governments, as well as individual households, after the president declares an emergency or major disaster.

The Center for American Progress examined FEMA data on weather- and wildfire-related disaster declarations between 2005 and 2015 to identify trends in FEMA disaster spending, which is funded by U.S. taxpayers. CAP found that:

- Between 2005 and 2015, FEMA issued more than $67 billion in grants to assist communities and individuals devastated by extreme weather and wildfires. Overall, FEMA spent about $200 per U.S. resident for disaster assistance during that time period.

- FEMA provided the most disaster assistance to Louisiana and New York, which, combined, received more than half of the agency’s total assistance over the 10-year period due to damage caused by Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy, respectively. Texas, Mississippi, and New Jersey rank third through fifth for FEMA disaster spending between 2005 and 2015.

- The states that received the most FEMA disaster assistance spending per capita were Louisiana ($4,345), Mississippi ($1,607), North Dakota ($843), and New York ($807). In North Dakota, unprecedented flooding events in 2009 and storms in 2011 caused substantial damage, driving up per-person costs among a smaller state population.

These findings likely underestimate the true federal cost—and thus the cost to taxpayers—of extreme weather. FEMA provides assistance in response to the worst natural disasters—those that triggered emergency and major disaster declarations. As a result, the findings do not include the costs of smaller but still destructive storms, costs borne by private insurers, and other government spending, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s disaster assistance program.

As the climate warms, these types of extreme weather and wildfire events could impose an even greater burden on American communities and taxpayers. In order to prepare for this reality, communities must invest in climate-resilient infrastructure and integrate climate considerations into their development plans.

Findings: FEMA is spending billions on natural disasters

Between 2005 and 2015, the president issued 832 separate emergency or disaster declarations for which FEMA provided either public assistance—defined as funding for state, tribal, and local governments—or individual assistance in the form of grants typically made to homeowners and renters whose home damage was not covered by homeowners insurance. (see text box)

Types of FEMA disaster assistance

In fiscal year 2015, Congress allocated $2.9 billion to FEMA federal assistance programs. The assistance FEMA provides in the wake of a presidentially declared emergency or major disaster typically takes one of two forms:

- Public assistance grants fund disaster recovery projects through state, tribal, and local governments and designated nonprofits. The recipients generally spend this money on debris removal, the repair and restoration of damaged public facilities, and other emergency measures.

- The Individuals and Households Program provides smaller grants to homeowners to repair property damage not otherwise covered through insurance. These grants can also cover temporary housing when an extreme weather event or other disaster displaces people.

In addition to these assistance programs, FEMA provides hazard mitigation assistance to prevent or mitigate long-term risks associated with natural disasters. FEMA also offers fire management assistance to state, local, and tribal governments for the “mitigation, management, and control” of certain fires in forests or grasslands. This issue brief only focuses on the public and individual/household assistance programs that are available after a disaster declaration.

Between 2005 and 2015, FEMA spent $67.7 billion on household and public assistance in response to presidentially declared emergencies and major disasters. Of this amount, $14.36 billion was spent on individual and household assistance, and public assistance outlays to state, tribal, and local governments made up the rest—$53.31 billion.

During this 10-year period, there were extreme weather and wildfire events in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and several U.S. territories and throughout all seasons. Severe storms were the most frequent cause of disaster declarations, with 470 distinct declarations across the examined time period. Although less common than severe storms, hurricanes caused the most damage. Between 2005 and 2015, FEMA spent $49.5 billion on public and individual assistance to help communities recover from hurricanes. FEMA spent $12.7 billion for assistance related to severe storms over the same 10-year period. (see Table 1)

Hurricanes accounted for eight of the top-10 costliest disaster declarations between 2005 and 2010, including hurricanes Katrina, Sandy, Ike, Wilma, Rita, Gustav, Irene, and Isaac. (see Table 2)

Accordingly, although the total assistance by state varied widely, FEMA directed significant disaster spending to states that experienced historic hurricane damage during the period examined. These states include Louisiana and Mississippi, where Hurricane Katrina hit hardest in 2005, and New York and New Jersey, where Hurricane Sandy landed in 2012. (see Table 3) Nationwide, FEMA spent more than $22 billion in assistance responding to Hurricane Katrina, including allocations for states that provided assistance related to evacuations. The agency provided nearly $16 billion in household and public assistance grants in response to Hurricane Sandy.

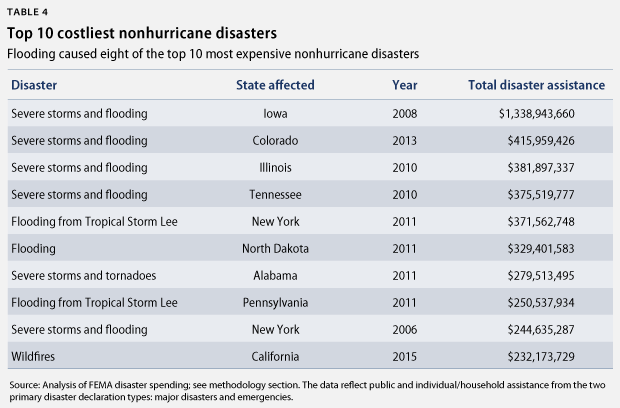

Nonhurricane events can cause significant and costly damage as well. In August 2016, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, experienced historic flooding from torrential rainfall. As of August 23, 2016, the floods had killed 13 people, and more than 100,000 people had applied for federal assistance. Preliminary analysis from Climate Central and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, found that increased temperatures due to climate change increased the likelihood of intense downpours in Louisiana by 40 percent. Floods are among the most costly extreme weather events that can hit an area, as they can destroy large areas of property and can take a long time to recede. Between 2005 and 2015, flooding caused eight of the 10 costliest nonhurricane disaster declarations and occurred across several different regions. (see Table 4)

Looking at the per-capita costs of extreme weather reveals that these disasters have a profound impact on individuals and communities. Louisiana received $4,345 per person in FEMA disaster spending between 2005 and 2015, the most of any state. Mississippi received the second-highest amount per capita—more than $1,600. Overall, FEMA spent about $200 per U.S. resident for disaster assistance between 2005 and 2015. (see Table 3)

Damage is not just limited to coastal areas. States in the central United States with relatively small populations have been hit hard by extreme weather and subsequently received significant assistance from FEMA. North Dakota, for example, ranks third for per-capita FEMA assistance over the analyzed decade due largely to eight distinct flooding events. Iowa ranks fifth for per-capita FEMA spending and seventh for total spending because of severe storms that caused major statewide flooding in 2008. Of the 10 states with the highest per-capita spending, half are located in the central United States. (see Table 3)

Conclusion

Extreme weather is already costing taxpayers and the federal government valuable public dollars and resources. Americans have recognized these costs; in a 2015 New York Times survey, 83 percent of respondents said that unmitigated climate change poses “a very or somewhat serious problem in the future.”

Because of the damage already caused to the climate, communities in the United States and around the globe will experience more frequent and intense extreme weather events, even if world leaders take immediate action to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Faced with this reality, FEMA has proposed a rule that would establish a deductible for disaster assistance in order to encourage states to make investments in resilience measures before disasters occur. This rule could incentivize states to invest in climate-smart infrastructure to minimize the financial and human toll of extreme weather.

The FEMA proposal is one among many efforts to push communities to better prepare for storms, floods, and other natural disasters—an effort made even more urgent because of climate change—rather than focusing only on responding to a disaster’s aftermath. Resilience, however, is only one prong in a coordinated response to climate change. The world must also focus on mitigating the worst impacts of climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning the global economy to cleaner, low-carbon forms of energy.

Methodology

CAP examined FEMA data on presidential declarations of major disasters and emergencies between 2005 and 2015. The data reflect the two primary disaster declaration types: major disaster and emergency. CAP analyzed FEMA data on public and individual/household assistance spending in response to these declarations. The data were last updated on July 12, 2016.

For the per-capita analysis in Table 3, CAP used population data obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. To calculate the per-capita costs by state, CAP averaged the state population totals from 2005, 2010, and 2015. The national per-capita figure in Table 3 reflects FEMA disaster assistance to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories.

CAP developed a methodology for excluding and including disasters to ensure the analysis only includes declarations that reflect the types of events that could become more common with unmitigated climate change.

We included public and individual assistance payments made in response to major disaster declarations and emergency declarations for the following types of incidents: coastal storms, drought, flooding, freezing, hurricanes, mudslides from flooding, severe ice storms, severe storms, snow, tornadoes, typhoons, and wildfires. We excluded public and individual assistance payments made for the following types of incidents that occurred between 2005 and 2015: water main breaks, terrorism, explosions, earthquakes, chemical spills, tsunamis, the 2009 presidential inauguration, bridge collapses, and volcanoes.

Erin Auel is a Research Assistant with the Energy and Environment team at the Center for American Progress. Alison Cassady is the Director of Domestic Energy Policy at the Center. The authors thank Charles Harper, a former intern at the Center, for his contributions to this issue brief.