The Arctic is in need of near-term temperature control. It is warming at a higher rate than the global mean and is experiencing climate impacts, such as thawing permafrost and rapidly melting sea ice, that have adverse effects on not just the region but also the global climate system.

Reductions in methane emissions are key to decreasing the rate of near-term warming and are an essential component of an overall greenhouse gas-mitigation strategy. The United States, which assumes the chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2015, could bring about significant progress on Arctic and global climate protection by making methane reduction a priority of its agenda.

About the Arctic Council

The Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum, was established in 1996 by the Ottawa Declaration to address issues of concern to Arctic nations and the region’s indigenous people. It has eight member nations—Canada, the United States, Finland, Iceland, the Russian Federation, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden—and 12 nations with observer status—France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, the United Kingdom, China, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and India.

The Arctic Council is an ideal forum to address methane emissions for a number of reasons. For example, Arctic nations have a common and heightened stake in methane mitigation. Not only would methane reductions slow warming globally, but they also would disproportionately benefit the Arctic, with two to three times the avoided warming as the global average. In addition, Arctic Council member and observer nations account for a significant portion—42 percent—of global anthropogenic methane emissions. Reductions in methane emissions from Arctic Council participants alone could therefore make a substantial difference to global methane levels.

The Arctic Council is aware that methane is a critical concern for its region. Since 2009, the forum has convened a task force focused on black carbon and methane. The current incarnation of the task force is developing strategies to reduce methane and black-carbon emissions and will report its recommendations at the next Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting in Iqaluit, Canada, in 2015.

Through its chairmanship, the United States has an opportunity to lead Arctic Council member and observer nations to take international action to curb methane emissions. The United States should promote the findings of the task force and advocate for the widespread implementation of its recommendations. Furthermore, the United States should take the lead in forging an agreement among Arctic nations on methane reductions and encouraging the participation of observer nations. Given its recent domestic actions focused on addressing methane emissions from sectors such as agriculture, oil and gas, and waste, the United States is a credible leader in this area.

The Center for American Progress has advocated that the United States should make climate change the overarching theme of its Arctic agenda. By making methane reductions a key component of this agenda, the United States could bring about a meaningful decrease in the rate of near-term Arctic and global warming.

Climate impacts in the Arctic and their global implications

The rate of warming in the Arctic is approximately twice the global average. As a consequence, sea-ice extent has decreased since 1979 at a rate of 3.5 percent to 4.1 percent per decade, with the lowest observations of minimum sea-ice extent occurring in the past seven years. Meanwhile, permafrost temperatures have increased by up to 2 degrees Celsius during the past 30 years, with the southern edge of permafrost in Russia and Canada receding northward. In addition, the social and economic hardship of Arctic communities is expected to intensify as a result of climate impacts. For example, changes in biodiversity due to rising sea temperatures threaten fishing enterprises, rising sea levels threaten coastal populations, and thawing permafrost threatens infrastructure.

Climate impacts in the Arctic have a series of global effects. As the planet loses sea ice, it decreases its capacity to reflect solar energy, which accelerates warming and causes a feedback loop. As permafrost thaws, carbon stores escape into the atmosphere in the form of methane and carbon dioxide, which again accelerates warming and causes a feedback loop. And as Arctic land ice melts, global sea levels rise. More than half of the global sea-level rise between 2003 and 2008 was caused by melting from Arctic glaciers, ice caps, and the Greenland Ice Sheet.

Methane reductions would decrease the rate of near-term warming

Reductions in methane emissions are a key means of reducing near-term warming and are necessary for an overall climate strategy.

About methane

Compared with carbon dioxide, or CO2, methane has a short atmospheric lifetime. It remains in the atmosphere for approximately 12 years, while CO2 can remain in the atmosphere for millennia. Methane is therefore classified as a short-lived climate forcer, along with black carbon, tropospheric ozone—also known as ground-level ozone—and some hydrofluorocarbons.

Although methane is removed from the atmosphere more quickly than CO2, it is much stronger in terms of warming potential. According to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, methane causes approximately 30 times as much warming as an equivalent mass of CO2 over a 100-year time frame and approximately 85 times as much warming over a 20-year time frame.

The atmospheric concentration of methane is now approximately 150 percent higher than preindustrial levels due to human activities, and methane emissions have increased by 47 percent since 1970. Moreover, global methane emissions are expected to increase by 25 percent by 2030 without new and additional mitigation measures. Oil and gas systems, agriculture, wastewater treatment, and landfills are primary anthropogenic sources of methane emissions.

Benefits of methane mitigation

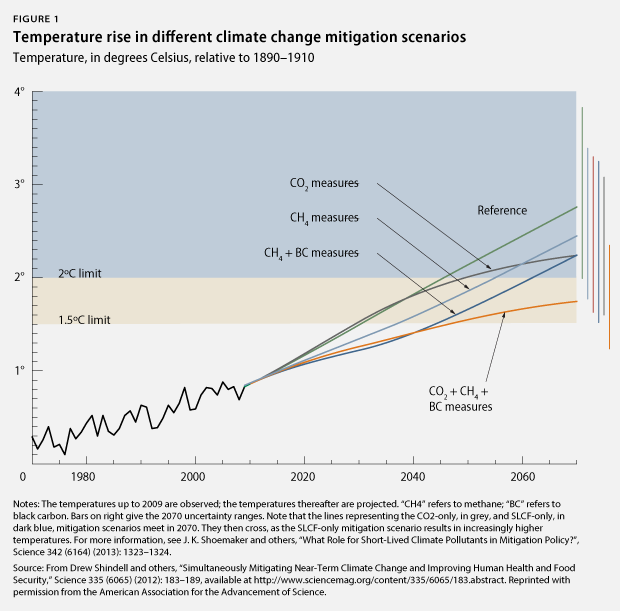

In order to maximally slow the rate of near-term warming, it is necessary to mitigate methane emissions. Because of the brief atmospheric lifetime of methane, the effect of emissions reductions will be felt within years. In contrast, CO2 reductions will not affect global mean surface temperature until approximately 2040. (see Figure 1)

While CO2 reductions are not a substitute for reductions in short-lived forcers, it is important to note that the converse is also true. Carbon dioxide control is required for the long-term stabilization of the climate, so a two-pronged mitigation strategy is necessary.

As Figure 1 illustrates, action on both carbon dioxide and short-lived climate forcers, or SLCFs, results in the lowest possible trajectory of temperature rise and offers the best chance of stabilizing the climate within a 2 degree Celsius increase above preindustrial levels.

Reductions in methane emissions would improve human health and crop yields in addition to benefiting the climate. Methane contributes to the formation of tropospheric ozone, which is not only a short-lived forcer but also an air pollutant and a primary component of smog. It is estimated that a 20 percent reduction in anthropogenic methane emissions would avert approximately 370,000 premature mortalities globally through 2030.

The Arctic Council is an ideal forum to address methane emissions

There are a number of reasons why the Arctic Council in particular is an ideal forum to focus on methane mitigation. They are outlined below.

Methane reductions are a primary means of Arctic climate protection

As already discussed, the Arctic is currently warming at a higher rate than the global average and is already experiencing effects such as thawing permafrost and melting sea ice. The region is in particular need of immediate temperature control, which realistically can be brought about in the near term only through reductions in methane and black-carbon emissions.

Moreover, although methane is homogeneously distributed around the globe regardless of where it is emitted, the effect of methane reductions on regional surface warming is not uniform. According to a recent report from the World Bank and the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, the Arctic stands to disproportionately benefit from methane-mitigation measures, with two to three times as much avoided warming as the global mean. When coupled with black-carbon-mitigation measures, the report estimates a reduction in Arctic warming of more than 1 degree Celsius by 2050, which amounts to reductions of up to 40 percent in melted summer sea ice and 25 percent in melted spring snow cover. A study by the United Nations Environment Programme, or UNEP, estimates that methane and black-carbon measures can reduce Arctic warming by 0.7 degrees Celsius by 2040, which amounts to decreasing temperature rise by approximately 67 percent below a business-as-usual scenario.

Although much attention regarding the potential of reducing short-lived forcers has focused on black carbon, the climate benefits of decreasing black carbon are dependent on location—such as proximity to snow and ice—and on wind conditions. Methane reductions always carry clear early climate benefits wherever the methane is emitted. This is also due to the fact that methane contributes to the formation of a second short-lived forcer, tropospheric ozone, so methane mitigation has a double benefit.

Arctic nations and observers account for a substantial portion of global methane emissions

The eight Arctic Council member nations account for 18 percent of global anthropogenic methane emissions, and the 12 observer nations account for 24 percent, for a total of 42 percent of global methane emissions. In addition, the world’s top four methane emitters—the United States, the Russian Federation, China, and India—are members or observers of the Arctic Council.

Moreover, there is great potential for methane mitigation. Effective and low-cost measures exist that reduce methane emissions from oil and gas systems, agriculture, waste, and wastewater management, which are the main sources of methane emissions. Options for methane mitigation and their feasibility have been well mapped and analyzed.

The United States therefore has an opportunity to bring about significant reductions in methane emissions and significant progress on slowing near-term warming through its leadership of the Arctic Council. It could, for example, take the lead in securing an agreement among Arctic nations that includes targets for reducing methane and black carbon, and it could encourage the participation of observer states in this agreement.

In addition, by making methane and the upcoming findings and recommendations of the Arctic Council Task Force on Short-Lived Climate Forcers a priority, the United States could promote involvement in methane-mitigation partnerships and initiatives, such as those of the Climate and Clean Air Coalition.

The Arctic Council has a pivotal role to play in the promotion of global methane reductions

The Arctic Council is an ideal forum to publicize the adverse effects of methane. By making methane reductions a cornerstone of its chairmanship, the United States could raise global awareness regarding the following facts:

- The Arctic is warming at a higher-than-average rate, which has a cascade of dangerous effects around the world.

- Reductions in short-lived forcers, such as methane and black carbon, are the means of slowing near-term Arctic and global warming.

By bringing these narratives to other forums and methane emitters, the Arctic Council could encourage reductions beyond its member and observer nations.

The Arctic Council could also instigate methane reductions outside its members and observers through levers such as official development assistance, or ODA, for methane-mitigation projects in the least developed countries.

Conclusion

From a climate perspective, the United States is assuming the chairmanship of the Arctic Council at an opportune time. The role of methane in global warming and the near-term benefits of methane reductions are now scientifically well understood, and the options for methane mitigation—as well as the cost effectiveness of these options—are well mapped. Moreover, international awareness is increasing regarding the necessity of methane reductions, and the United States has positioned itself as a strong leader on methane mitigation through its recent domestic actions. Given these factors, it is possible for the United States to lead significant international action on methane and other short-lived climate forcers and to be at the forefront of a considerable slowing of near-term warming under its chairmanship of the Arctic Council.

Gwynne Taraska is a Senior Policy Advisor at the Center for American Progress and the research director of the Institute for Philosophy and Public Policy at George Mason University. Patrick Clouser is a research assistant at the Institute for Philosophy and Public Policy and a student at George Mason University.

The authors thank Cathleen Kelly and Rebecca Lefton at the Center for American Progress, Pam Pearson at the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, and Benjamin DeAngelo at the Environmental Protection Agency for their comments on this brief. The views and recommendations in this brief do not necessarily reflect those of the Environmental Protection Agency.