A review of the U.S. Department of the Interior’s most recent oil and gas leasing data along with a new map of water scarcity in the American West shows that the Trump administration’s efforts to expand fossil fuel development on U.S. public lands could endanger the quantity and quality of water that is available to farmers, towns, and other water users in the region.

According to the Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, published by the World Resources Institute (WRI), several states in the Western United States suffer from narrow margins of water availability. New Mexico, in particular, currently faces water stress equivalent to the 10th-most water-stressed country in the world, the United Arab Emirates.

As the gap between water supply and water demand narrows across the West, farmers, ranchers, communities, and policymakers are working to reduce their water footprint and find efficiencies.

However, one major water use in the West—oil and gas exploration and production—continues to grow relatively unscrutinized. The oil and gas industry often requires millions of gallons of water to drill and produce oil from a single well. Active oil fields—such as those in the Permian Basin in New Mexico—can have thousands of wells, putting significant strain on water supplies.

A CAP analysis of the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) leasing data finds that, over the past two and a half years, the Trump administration has offered the oil and gas industry the opportunity to buy thousands of oil and gas leases in some of the most arid and water-stressed areas of the country. The significant overlap of water-stressed areas in Western states and recent oil and gas leasing deserves greater scrutiny.

The water stressed American West

To conduct the analysis for this column, CAP cross-compared publicly available data on federal oil and gas lease sales with the WRI’s Aqueduct data to determine the extent to which the BLM’s oil and gas leasing programs occur in areas of increased water stress.

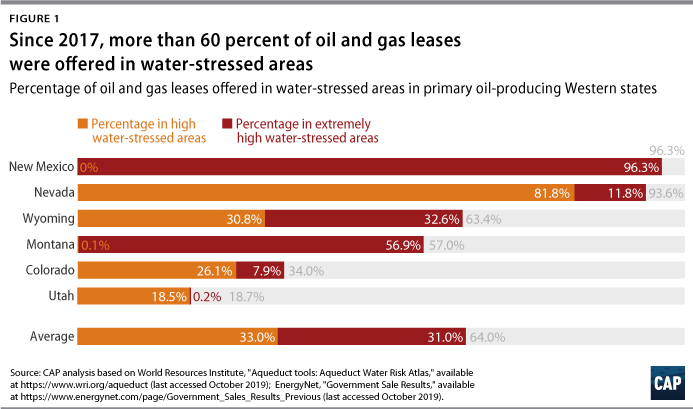

CAP found that, since the start of the Trump administration, the BLM has offered more than 5,550 oil and gas leases in the Intermountain West. Of these leases, more than 6 in 10 have been in areas suffering from “high” or “extremely high” water stress, as defined by the WRI.

The issue of oil and gas leasing in arid areas is particularly acute in Nevada and New Mexico. In Nevada, 1,050 of 1,122 leases—almost 97 percent—were offered in areas of “high” or “extremely high” water stress. This conflict has caused some local officials to push back on oil and gas leasing. For example, in Nevada, both the mayor of Henderson and the Clark County commissioner have warned of the threat that upcoming lease sales pose to the region’s drinking water supplies.

In New Mexico, 387 of 402 leases—more than 95 percent—offered under the Trump administration are located in “extremely high” water-stress areas. The Permian Basin, which runs through southeastern New Mexico, is one of the largest oil and gas producing regions in the world. Leasing activity has been at an all-time high, and up to 2.6 million gallons of water are used to frack a single well in this region.

Other less arid states are also at risk. In Wyoming, where more than 1,400 federal leases have been offered, 63 percent were in water-stressed areas, with about half of those in “extremely high” stress areas. In Montana, where 57 percent of leases were offered in water-stressed areas, all but 1 percent were considered “extremely high” stress.

More data is needed to understand the water energy nexus

Earlier this year, a CAP analysis found that there is a dearth of information related to the amount of water that energy development uses—either in aggregate or at a project-specific level. There are no standard reporting requirements for energy companies on water, so available data relies on voluntary industry reporting; varies in quality; and doesn’t typically distinguish between drilling methods or water sources.

Furthermore, the BLM has not developed adequate guidance for how the agency should take water impacts into consideration for oil and gas leasing decisions. As a result, the agency is inconsistent in whether and how it weighs the potential impacts on water quantity and quality in environmental analyses and resource management planning. The glaring gap in analyses may ultimately put some BLM leasing decisions in jeopardy. In fact, a recent court decision cited the BLM for failing to consider the cumulative impacts of oil and gas development on water in northwestern New Mexico, saying, “[T]he BLM needed to—but did not—consider the cumulative impacts of water resources associated with the 3,960 reasonably foreseeable horizontal Mancos Shale wells.” Without a shift in policy, the BLM will continue to lease in highly stressed water basins where the additional water demand may impact farmers, ranchers, and the surrounding communities.

Conclusion

With water already scarce—and growing scarcer in much of the West—considering water impacts should no longer be optional when it comes to oil and gas leasing. A new Senate bill has taken a good start by directing the U.S. Geological Survey to track the water used for energy development in the West as part of their Water Availability and Use Science Program. Accurate, detailed, and consistent information on energy development’s effects on water would provide invaluable data to stakeholders who depend on clean water for their livelihoods and daily living; policymakers; and land and water managers.

In addition, the BLM should develop specific agencywide guidance to ensure adequate and consistent consideration of potential energy-development impacts on watersheds. The author suspects that the average American assumes the government is already applying this lens when they make decisions about oil and gas leasing on public lands. However, as the data shows, this is far from the truth.

Jenny Rowland-Shea is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Atiba Kimbrell, Kate Kelly, Matt Lee-Ashley, Ryan Richards, Nicole Gentile, Will Beaudouin, Christian Rodriguez, and Chester Hawkins for their contributions to this column.

Methodology

CAP’s analysis used data from oil and gas lease sales held from January 2017 through October 2019 (though this is not a problem limited to that time period) in the six states where the majority of BLM leases are offered. The authors used lease sale data available in a geographic information system-ready (GIS) format through EnergyNet with the exception of the February 2017 sale in Wyoming and the September 2018 sale in Nevada, where available spatial data found on the BLM’s website was used. However, available spatial data for the September 2018 Nevada sale does not appear to cover all leases offered. The authors chose to review leases offered versus leases bought because it provides the most accurate picture of where the Trump administration believes energy development should take place.

The GIS water stress data were downloaded from WRI’s Aqueduct Water Stress Projections database. Indicators identifying “physical risks quantity” were used rather than the overall water risk score because the overall score included wastewater and other institutional measures that were not relevant to this study. Leases were considered to be offered in risky areas when the location had a risk category of “high” or “extremely high” water stress according to the WRI data. High water stress is defined as areas where water withdrawals hit a threshold of 40 percent to 80 percent of the available renewable water supplies. In extremely high water stress areas, these water withdrawals account for more than 80 percent of the renewable water supplies.