In 2018, the Trump administration put forward a highly controversial plan to expand offshore drilling off the U.S. Pacific and Atlantic coasts, the west coast of Florida in the Gulf of Mexico, and Alaska. Though this drilling proposal has been delayed as a result of litigation, coastal communities remain deeply concerned that the administration’s final decision will irreversibly damage the health of America’s coastal and marine environments.

Opposition to the Trump administration’s offshore drilling plan has been widespread and bipartisan. It includes governors from 17 coastal states; more than 330 municipalities; more than 2,100 local, state, and federally elected officials; the U.S. Department of Defense; the U.S. Air Force; the Florida Defense Support Task Force; NASA; and an alliance representing more than 43,000 businesses and 500,000 fishing families. Furthermore, 60 percent of voters oppose expanding offshore drilling, and more than 70 percent favor giving states the power to veto federal offshore drilling plans near their coastlines. A recent House bill to ban offshore drilling in the Atlantic and Pacific Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) planning areas passed the House with 238 votes, including 12 votes from Republicans.

Global consequences of Trump’s offshore drilling plan

The vast scale of the Trump administration’s drilling plan deserves more scrutiny and attention. Not only would it risk additional catastrophic oil spills, but it would also burn vastly more fossil fuel at a time when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that the world has just 11 years to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to avoid the worst effects of climate change. In 2016, the Obama administration recognized the severity of the climate crisis and issued National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) climate change guidance. This guidance required agencies to consider climate effect in their federal decision-making, including projects involving infrastructure, oil and gas leasing, and pipelines. Yet President Trump rescinded this guidance soon after his inauguration, leaving agencies such as the U.S. Department of the Interior without a template on how to assess climate impacts.

Increase in greenhouse gas emissions

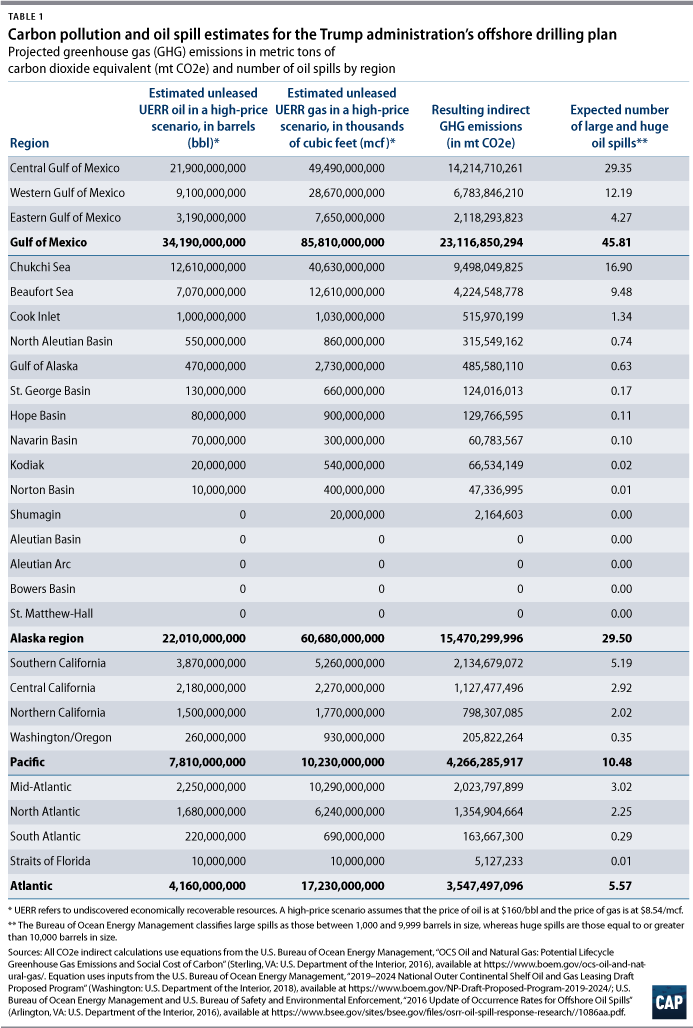

Since Trump’s proposed plan fails to outline its true costs, CAP used calculations outlined by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to determine the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that would result from the plan’s implementation.

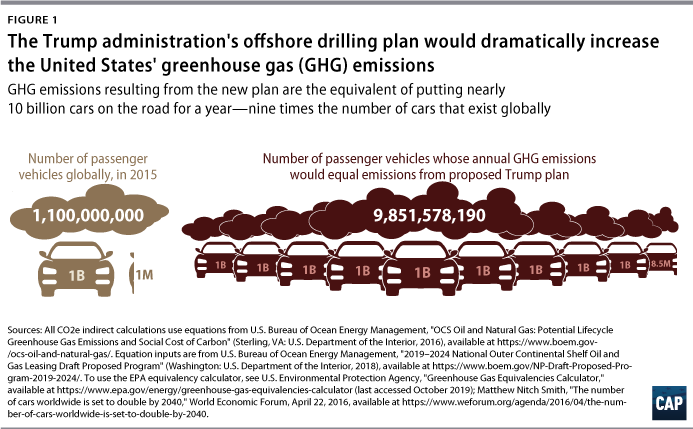

The data show that if this plan were implemented, the resulting combustion of the additional fossil fuels extracted would add as many as 46 billion metric tons of GHG emissions to the world’s atmosphere. That is nearly seven times more than all GHG emitted by the entire United States each year. Put another way, such an increase is the equivalent of the yearly emissions from nearly 10 billion cars—nine times as many cars as are on the road worldwide today.

This vast increase in emissions has global consequences. In order to limit global temperature rise to fewer than 2 degrees Celsius, the world must restrict global emissions to fewer than 1 trillion tons of carbon, which was the central goal of the Paris climate agreement. According to current estimates, more than half of this carbon “budget” has already been emitted. The 46 billion metric tons of carbon that would be released by Trump’s plan would account for more than 3 percent of what remains in the entire global carbon budget.

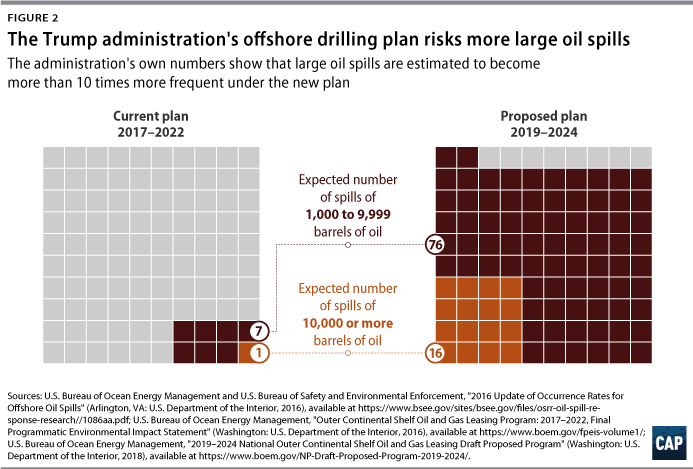

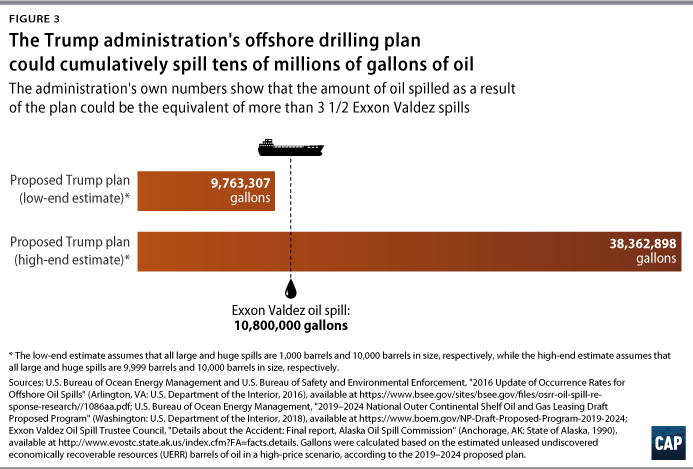

More large oil spills

According to CAP estimates, the Trump administration drilling plan would also lead to more than 10 times more large oil spills than the current plan. (see Figure 2) Based on the spill rate associated with increased drilling activity, the number of large oil spills—those of at least 42,000 gallons, or 1,000 barrels—would increase from eight to 92 over the 30-year course of the plan. For comparison, the 2015 Santa Barbara oil spill that caused significant damage to beaches and wildlife spilled approximately 140,000 gallons. Even if all 92 oil spills were the minimum size in their respective class—42,000 gallons for large spills and 420,000 gallons for huge spills—this would still lead to more than 9 million gallons of oil being spilt into the ocean. For context, the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster spilled nearly 11 million gallons into Prince William Sound, which is still polluted to this day.

Yet even this significant increase in large oil spills is likely a conservative estimate for two reasons. First, this spill rate excludes rare, catastrophic events such as the 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident in the Gulf of Mexico, which BOEM deemed an outlier, or the ongoing Taylor Energy leak, which may actually be one of the largest spills in history. However, if the Trump drilling plan went fully into effect, it would increase the likelihood of such catastrophic oil spills. Second, this estimate does not account for the impacts of increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather. The government’s own 2018 analysis on oil spill occurrence frequencies in the OCS regions shows that extreme weather will likely be more of a problem for drilling in the newly opened Atlantic Ocean than it has been in the Gulf of Mexico, since hurricanes are expected to hit the Atlantic coast twice as often as they hit the Gulf. Meanwhile, in the Arctic Ocean, low temperatures are likely to increase incidents of human error and instances of equipment and mechanical failure. These two factors are already the main causes of small and medium oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico, but they could also lead to more and larger oil spills in the Arctic, where there is little to no infrastructure to handle a spill and no response plan in place.

Conclusion

The health of the world’s climate and ocean—as well as 2.6 million sustainable jobs and $180 billion in gross domestic product—is at risk. These resources are worth more than the potential of tapping fossil fuel reserves that would meet only six years of the nation’s oil demand and natural gas needs. Trump’s offshore drilling plan deserves to remain where it is: sunk deep in the courts, out of sight and unimplemented.

Margaret Cooney is the campaign manager for Ocean Policy at the Center for American Progress. Mary Ellen Kustin is the former director of policy for Public Lands at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Miriam Goldstein, Matt Lee-Ashley, Sally Hardin, Marc Rehmann, Steve Bonitatibus, and Chester Hawkins for their contributions to this column.

Methodology

CAP’s GHG analysis uses the estimated extractable amount of oil and gas in the National OCS Oil and Gas Leasing draft proposed program (DPP). CAP used data given for a high-price market scenario of oil selling for $160 per barrel (bbl) of oil and natural gas for $8.54 per thousand cubic feet (mcf). The DPP states that the new plan would lead to the extraction of up to 68.17 billion bbl of oil and up to 173.95 billion mcf of gas. Using calculations outlined in the BOEM’s 2016 “OCS Oil and Natural Gas” report as well the EPA’s GHG conversions rates, CAP calculated indirect carbon dioxide equivalent emissions—emissions associated with combustion—based on the predicted oil and gas extraction amounts stated in the DPP. These calculations include the full “indirect” carbon dioxide equivalent emission estimates for carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide but do not include “direct” emissions from the drilling and extraction process itself.

For the carbon budget calculation, CAP used the Global Carbon Project’s cumulative carbon emission estimates to calculate that there are only 385 gigatons of carbon (GtC) left in the global budget. The subsequent calculations for carbon emissions in the DPP would spend 3.35 percent of what is left.

To calculate the likelihood of spills, CAP used spill rates given for billions of barrels handled via offshore platforms and pipelines provided in the BOEM and Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) “2016 Update of Occurrence Rates for Offshore Oil Spills.” CAP did not include natural gas in the spill rate because it was not included in the above report, but rather estimated spill rates based on the DPP’s assessment that the new plan would lead to the extraction of up to 68.17 billion bbl.