On April 26, President Donald Trump launched an attack on national parks, public lands, and waters. His executive order called on U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke to “review” the 54 national monuments that presidents have designated or expanded since 1996. The order gives wide discretion to the secretary to recommend actions that the president or Congress should take to alter or rescind the protections for these natural, historical, and cultural treasures.

While the order is written in such a way that all recent national monuments—including the Stonewall, César E. Chávez, Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality, and Pacific Remote Islands Marine national monuments—are subject to the 120-day review, Secretary Zinke publicly called out two monuments: The “bookends” of his review will be the Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments, both located in Utah. These two monuments later made the list of monuments Secretary Zinke is initially reviewing.

It has been widely reported that the Utah congressional delegation was the driving force behind President Trump’s executive order. Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and Rep. Rob Bishop (R-UT) have been particularly outspoken in their opposition to the Antiquities Act writ large and to Utah’s national monuments specifically. Indeed, both were at the signing ceremony for the executive order; Utah Gov. Gary Herbert (R) and Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) were also in attendance. President Trump gave Sen. Hatch the pen he used to sign the order after recognizing Hatch as “tough” for repeatedly calling Trump to say “you got to do this.”

The national monument review will be a legal, moral, and political minefield. President Trump’s embrace of the Utah delegation and its pet cause is especially interesting given that most of the delegation’s members were vocal in their opposition to him during the presidential primary. For a president known to keep a list of those who speak ill of him, it is a curious alliance. The Center for American Progress’ analysis suggests that a closer look at the oil, gas, and coal underneath Utah’s national monuments—and the fossil fuel industry’s influence on Trump and the Utah delegation—might help explain this newly formed partnership.

The Trump administration and the Utah delegation’s history of disagreement

President Trump struggled to find support in Utah during his campaign, with the majority of the state’s voters supporting someone else in both the Republican caucuses and the general election. Rep. Bishop reluctantly voted for Trump, saying, “Unless he resigns, I must support the Republican nominee as my only option.” Sen. Hatch eventually supported Trump, but only after endorsing two other Republican candidates first. And Utah’s junior senator, Mike Lee, another critic of the Bears Ears National Monument, told constituents that Trump “scares [him] to death.” Similarly, Utah Rep. Chris Stewart (R) said last year that “Donald trump does not represent republican ideals, he is our Mussolini.”

In addition, the Trump administration’s early policy statements on land management differ from those of the Utah delegation. During the campaign, Trump indicated in an interview with Field & Stream magazine that his administration would be “great stewards” of public lands and that he did not “like the idea” of transferring federal lands to the states. His pick of Secretary Zinke, who resigned his delegate post at the Republican National Convention over the party’s platform on this issue, underscored that commitment. By contrast, Rep. Bishop, Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-UT), and Sen. Lee (R-UT) have all introduced legislation that would make it easier to sell off public lands.

It is noteworthy, then, that President Trump is pushing an executive order that is a thinly veiled land seizure. He even parroted a land seizure activist talking point—embraced by Rep. Bishop and other proponents of diminishing federal land management—just before signing the order, saying he would “give that power back to the states and to the people, where it belongs.” Curious, perhaps, until one remembers that this rhetoric traces its roots to industry-backed front groups with vested interests in selling off public lands for private gain.

Extractive industries threaten national monuments in Utah

Both President Trump and members of the Utah delegation, particularly Rep. Bishop, have benefited from oil, gas, and coal industry contributions. Trump’s presidential campaign received more than $1.1 million from the fossil fuel industry. And coal, oil, and gas interests contributed $1 out of every $10 raised—a total of at least $10 million—for Trump’s inaugural celebrations. These events were not subject to the same campaign finance restrictions as donations made during the election.

Rep. Bishop, meanwhile, received the highest percentage of out-of-state campaign contributions of anyone in the House, and the oil and gas industries—including the American Petroleum Institute, a trade association that represents hundreds of oil and gas companies—contributed more to his campaigns than any other industry. Although Bishop has repeatedly claimed that his issues with the Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments have nothing to do with the fossil fuel interests located below them, both monuments appear to be in the sights of this heavily invested industry.

The American Petroleum Institute was quick to send a letter to House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Bishop and his counterpart in the Senate shortly after the 115th Congress convened, imploring them to “re-examine the role and purpose of the Antiquities Act.” The organization argued that the law threatens the extraction of fossil fuels from public lands and waters. In addition, the oil and gas industry group Western Energy Alliance, or WEA, has indicated interest in drilling in Bears Ears. WEA President Kathleen Sgamma has said about the monument, “There certainly is industry appetite for development there, or else companies wouldn’t have leases in the area.” And geologists have known for years that the Grand Staircase-Escalante area has coal, oil, and mineral deposits.

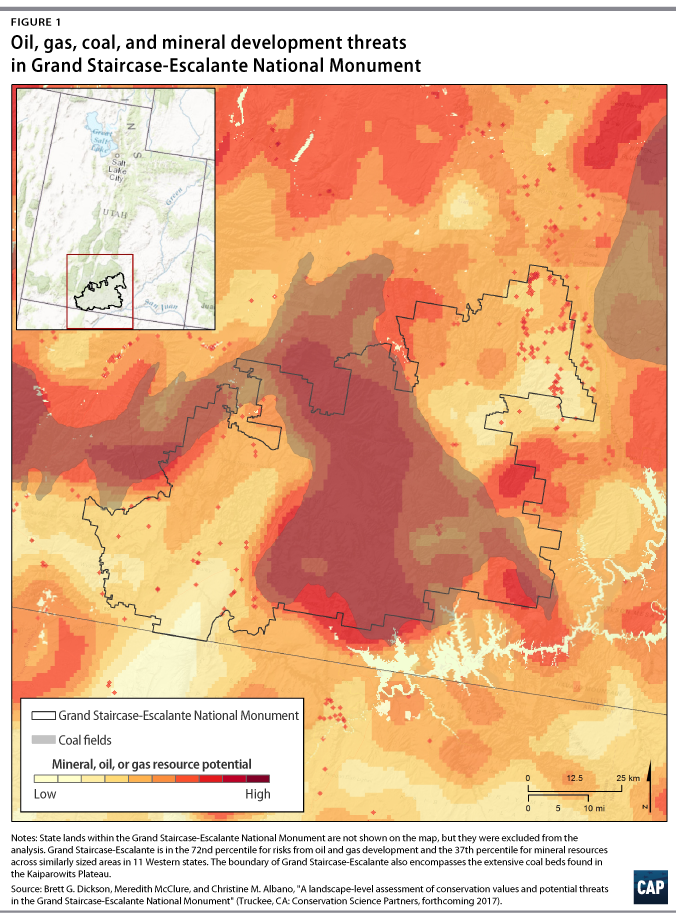

The following maps reveal why special interests would want access to mine and drill within the boundaries of both Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments. A new analysis by CAP and Conservation Science Partners, or CSP, finds that Grand Staircase-Escalante scored in the 72nd percentile for oil and gas and the 37th percentile for mineral resources among similarly sized Western landscapes. The boundary of Grand Staircase-Escalante also encompasses the extensive coal beds found in the Kaiparowits Plateau. As CAP and CSP previously reported, when compared with similarly sized landscapes in the West, Bears Ears scored above the 50th percentile for both mineral resources and oil and gas. Without protection, Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears would be at great risk of destructive mining and oil and gas development.

These national monuments are also two of the wildest and most ecologically valuable places in the West. The new analysis indicates that Grand Staircase-Escalante is in the top 4 percent for ecological intactness and the top 6 percent for connectivity, which are essential to biodiversity and landscape-level conservation. As CAP and CSP previously showed, Bears Ears is in the top 10 percent of similarly sized places in the West for these two important factors.

Even though national monuments are public lands that, by definition, belong to the people, President Trump said he was signing the executive order to “return control to the people—the people of Utah, the people of all the states, the people of the United States.” However, it appears the people he has in mind may be those with close industry ties.

Methodology

To determine the ecological importance of Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, CAP and CSP mapped and summarized 10 landscape-level indicators of resilience to climate change; ecological connectivity; and intactness, biodiversity, and remoteness. Publicly available spatial data and published methods of analysis were used to create indicator maps across 11 Western states to compare Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument with equivalently sized areas throughout the West. The same was done with each of seven national parks. A mixture of iconic Western national parks known for their ecological importance and Utah national parks were selected for comparison. CAP and CSP also assessed Bears Ears for two threat indicators: mineral resource potential and oil and gas resource potential. No coal resources were found within Bears Ears National Monument. Similarly, CAP and CSP assessed Grand Staircase-Escalante for three threat indicators: mineral resource potential, oil and gas resource potential, and coal resource potential.

CAP and CSP determined the values of each of the indicators relative to the larger landscape using a simple scoring system based on percentile ranks. Specifically, the mean value of each indicator within Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was compared with the distribution of means of a large random sample of 1,000 areas across the 11 Western states, including all jurisdictions. The size of the random samples was equivalent to the size of the monument. CAP and CSP did the same for the seven national parks. Scores on indicators ranged from 0 to 100. For example, a score of 98 for a given indicator signified that the mean value of that indicator in the monument was greater than or equal to 98 percent of the equivalently sized random samples. Scores of 50 or higher suggested a relatively important indicator.

A more detailed description of methods and data can be found here.

Mary Ellen Kustin is the Director of Policy for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Jenny Rowland, Kate Kelly, Meghan Miller, and Chester Hawkins for their contributions to this column.