On November 30, world leaders will meet in Paris for the 21st Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC. If the Paris summit is successful, it will produce a strong international agreement to curb global carbon emissions and improve resilience to the effects of climate change. There is momentum building for events in Paris—with more than 160 countries submitting goals for post-2020 emissions reductions—but there are still hurdles to reaching an agreement that would advance these goals together as a concerted global effort.

The role of finance in international climate cooperation

International climate finance is of central importance to the Paris summit: It will take a marked shift in investments to adapt to a changing climate and steer the global economy toward clean energy. Finance is a particular priority for the most vulnerable developing countries, which have contributed little to global carbon pollution but are acutely harmed by it. The effects of climate change pose a disproportionate threat to regions already beset with economic challenges, such as the Least Developed Countries, and to low-lying regions vulnerable to sea-level rise, such as the Small Island Developing States. Respect for the priorities of these blocs and financial support for their climate goals are important, both in themselves and for the prospects of reaching consensus for a new global agreement.

During the Copenhagen summit in 2009, developed countries pledged to collectively mobilize $100 billion per year in climate finance for developing countries by 2020. A recent report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, shows that there has been progress toward this goal, though further progress is necessary: Climate finance for developing countries reached $62 billion in 2014, with only approximately one-sixth of that total dedicated to adaptation.

In the months leading up to the Paris summit, many governments have showed their resolve to address climate change—and fulfill the Copenhagen commitment—by pledging funds to international channels such as the Green Climate Fund, or GCF, which aims to promote low-carbon development, elevate adaptation finance, and leverage investment from the private sector. The GCF has reached a total of $10.2 billion in pledges for its initial capitalization and approved its first tranche of projects this month.

How Canada and Australia could show leadership at the Paris summit

Canada and Australia—two countries that have developed reputations for climate obstructionism—elected new leaders this fall. In Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau committed to rejoin the global effort to address climate change. In Australia, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s record indicates that he may embrace more progressive policies than former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who is widely known as a climate denier.

By making new pledges to the GCF in Paris, Canada and Australia could show newfound leadership and ambition—and help re-establish their standings in the geopolitics of climate change.

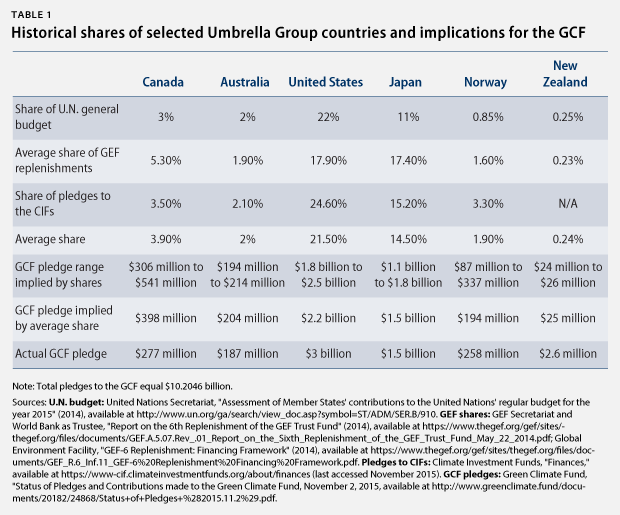

Under former Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the Canadian government pledged $277 million to the GCF last year. Meanwhile, the Abbott government in Australia pledged $187 million. These figures are not consistent with the countries’ historical contributions to multilateral efforts on climate or development assistance. (see Table 1)

Considering Canada’s contributions to older climate programs—such as the Global Environment Facility, or GEF, and the Climate Investment Funds, or CIFs—as well as to the U.N. general budget, a pledge of $398 million would be more in line with Canadian practice. Considering Australia’s contributions, a pledge of $204 million would be more in line with Australian practice.

Last November, the Obama administration pledged $3 billion to the GCF. This represents a progression over the pledge range one would expect based on previous U.S. contributions to the three multilateral efforts considered here. Should Prime Minister Trudeau’s government be similarly ambitious, Canada’s pledge to the GCF would be more than $541 million. Should Prime Minister Turnbull’s government take the same route, Australia’s pledge to the GCF would be more than $214 million.*

The table below shows Canada’s and Australia’s historical shares of multilateral fund totals and the U.N. general budget, as well as those of several allies that are also in the Umbrella Group of the UNFCCC, such as the United States, Japan, and Norway. It also shows the GCF pledges that these historical shares would suggest compared with the actual pledges made.

Conclusion

Increased pledges from Canada and Australia would bring these countries back in line with the global community with respect to international climate investment—which is an important pillar for success in Paris—and would communicate a clear message of commitment to the creation of a fair, lasting, and effective climate regime.

* Note: All figures in the column and table are in U.S. dollars. It is important to note that the $3 billion U.S. pledge is an increase over the figure implied by historical contributions but is in line with the figure implied by analyses that take into account responsibility for climate change.

Gwynne Taraska is a Senior Policy Advisor at the Center for American Progress, where she works on international climate policy.

The author would like to thank to Annaka Peterson—a senior program officer at Oxfam America who has worked on fair shares of the GCF—for reviewing a draft of this column. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily represent those of the reviewer; any errors are the responsibility of the author.