When President Barack Obama travels to Alaska in August to attend the Conference on Global Leadership in the Arctic: Cooperation, Innovation, Engagement and Resilience, or GLACIER, he is likely to see up close the determination of Alaska Natives to maintain their traditional hunting and fishing cultures; to obtain quality education and health care for their families; and to build sustainable economies. He is also likely to see firsthand the horrors of slow-onset climate catastrophe. The skyrocketing risks of climate change are forcing many Alaska Native communities to consider moving. Alarmingly, what is happening in Alaska is part of a much larger trend in the United States and globally in which a growing number of people are displaced by more extreme weather or other climate change effects.

Communities are sinking

On the west coast of Alaska, the low-lying land where Newtok—a small, remote community of Yu’pik Eskimos—sits, has been slowly giving way to the Ninglick River and the nearby Bering Sea. This Alaska Native village of roughly 350 people is sinking due to coastal erosion, permafrost thaw, and melting protective sea ice.

The land under Newtok has been eroding for decades, and climate change is making it worse. Higher temperatures thaw permafrost and melt the sea ice that normally shields Newtok from severe storms. According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Newtok has been losing its land at the staggering rate of 72 feet per year. In two years, it projects that the village’s highest point—the site of Newtok’s only school—could be underwater. As Alaska warms at more than twice the rate of the rest of the United States, the people of Newtok also face the unsettling reality of rising seas and stronger storms. In 2005, a severe September storm and flood destroyed Newtok’s barge landing, cutting off the village from essential supplies, including food, water, and fuel.

The plight of Newtok is not unlike that of other Alaska Native communities, many of which are also in low-lying coastal areas that are particularly affected by climate change. In 2003, the U.S. Government Accountability Office, or GAO, found that flooding and erosion affected 184 out of 213 Alaska Native villages, or 86 percent. Many of these communities do not have the resources to manage climate change risks on their own or to safely move out of harm’s way.

The hefty price tag of relocation

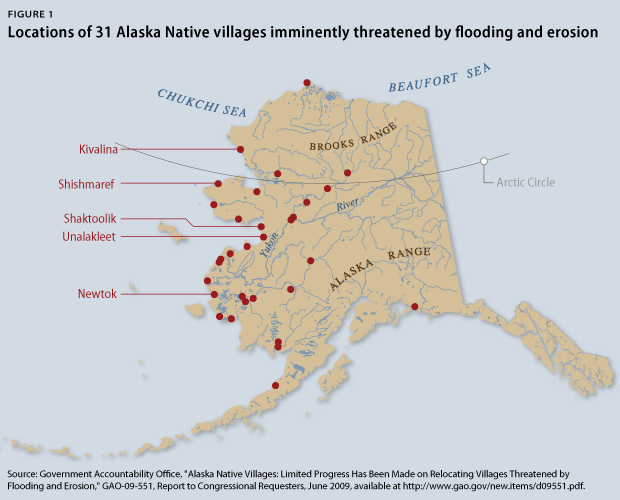

In response to these threats, the Army Corps of Engineers and state-funded programs have helped some of these villages take temporary steps to reduce erosion and flooding. For example, after a late November storm in 2003, the Corps helped Unalakleet, a community of about 300 people, construct a retaining wall to help shield the village from future storms. But the wall is not a sustainable solution and needs continuous repair. For Newtok, Unalakleet, and other Alaska Native communities—such as Kivalina, Shishmaref, and Shaktoolik—temporary fixes are not enough. In 2009, the GAO identified 31 Alaska Native villages that face an imminent threat of erosion and flooding, 12 of which have already begun to explore relocation.

Even as temperatures and flood risk rise, political, economic, and cultural challenges have prevented imperiled communities from relocating to higher and safer ground. The Army Corps of Engineers estimates that moving Newtok would cost up to $130 million, or as much as $380,000 per resident, with similarly hefty price tags for other Alaska Native communities. In addition, these communities have depended for centuries on long winters and ready access to the marine environment to hunt whales, bearded seals, walruses, and other essential sources of nutrition. In an interview with the author, Alaska Federation of Natives, or AFN, President Julie Kitka said, “Alaska Natives have hopes and dreams for the future as American and tribal citizens. Alaska Natives have many distinct cultural and ethnic groups, each with values and a culture that is very important to them.” For these communities, moving could mean not only losing their homes but also losing their traditional subsistence culture and way of life. Unlike many of the tribes in the lower 48 states with land held in trust by the federal government, most of the 229 federally recognized tribes in Alaska own and manage their land through a system of regional and village corporations established under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, or ANCSA. According to Kitka, Alaska Natives are the largest private landowners in the state, and risk losing the ability to live on their land, develop sustainable economies from their land, and contribute to society.

But for some Alaska Native communities, the question is no longer if they should move but when and how. Whether they wait for the slow onset of climate change damage to amass into uninhabitable conditions or for the next catastrophic storm, imperiled Alaska Native communities need relocation plans and resources to move, and they need them fast. Without such plans and resources, villagers may be forced to resettle in different locations and risk losing everything—their communities, land, cultures, and small foothold in the economy.

American Indian and Alaska Native communities face a number of unique circumstances that affect their ability to relocate, reduce climate change risks, and respond to catastrophe without support. First, American Indians and Alaska Natives endure the highest poverty rates in the country. According to 2007–2011 survey data from the Bureau of the Census, 27 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives live below the federal poverty line, higher than the overall U.S. poverty rate of 14.3 percent, as well as that of any other race or origin in the country. In addition, most tribal governments cannot collect income and property taxes due to these poverty rates and, in Alaska, because of the land ownership and management structure created by ANCSA. This means that they generally have few resources to cover relocation and disaster rebuilding costs.

President Obama can help

In the words of AFN President Kitka, “Native people have a tremendous desire to be involved in directing their own lives and working peacefully and constructively with others to do that.” When President Obama comes to Alaska in August, he can take three concrete steps to help Alaska Native villages chart a course to keep their cultures and communities intact in the face of climate change.

1. Expand federal resilience and relocation support

In November 2014, the State, Local, and Tribal Leaders Task Force on Climate Preparedness and Resilience recommended that President Obama “explore [the] Federal role in addressing climate change-related displacement” of people. In February 2015, Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell announced an $8 million award to strengthen tribal community resilience. While this support is useful, it is not nearly enough to help native communities manage climate change risks and, in the worst cases, plan and execute a move.

The president could help remedy this by increasing the flexibility of existing disaster assistance programs. For example, the president could direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, to update its draft guidance to clarify that tribal governments can request a presidential disaster declaration for slow-onset disasters that imminently threaten tribal communities, including when such disasters require a community to move. When deciding whether to declare a disaster and what assistance to offer, FEMA and the president should take into account economic and other damages to subsistence economies.

Additionally, the president can use his Stafford Act authority to waive the cost-sharing requirement for the Public Assistance Program, which supports emergency protective measures and the rebuilding of damaged schools, community centers, and other public infrastructure. According to AFN, the cost-sharing requirement—even when reduced from 25 percent to 10 percent as FEMA occasionally does for “extraordinary” cases—makes it nearly impossible for Alaska Native communities to access federal disaster assistance support. By waiving the Public Assistance Program cost-sharing requirement for tribes that simply cannot meet it, the president can give communities facing catastrophe access to the resources they need to move critical public infrastructure out of harm’s way. Just as importantly, the federal government has a legal obligation through the Constitution and various treaties to American Indians and Alaska Natives to protect treaty rights, lands, and other assets and to provide for their general health, education, and welfare. This obligation is known as the federal “trust responsibility.” Resilience and relocation support for these villages should be no exception. Lastly, the president and federal agencies can strengthen native communities’ capacity to self-direct their resilience and relocation efforts by giving them accurate and timely climate risk information; by working closely with native community leaders and native governing entities; by encouraging tribal contracting and compacting for resilience and relocation projects; and by helping integrate traditional knowledge into resilience solutions.

2. Designate the Denali Commission as the lead federal agency for strengthening community resilience

The Denali Commission is an independent federal agency that Congress created in 1998 to promote economic development and sustainable infrastructure in rural Alaska. At its peak in fiscal year 2007, the commission received $141 million in annual appropriations. However, its funding has steadily declined since then. In FY 2014, the commission received $14 million—a 90 percent drop relative to 2007 levels.

As it stands, there is currently no federal agency charged with leading and coordinating rural Alaska community resilience and relocation efforts. Without a lead agency, delays and other barriers to securing the technical and financial support for community resilience and relocation efforts are exacerbated.

The president could help fix this by reauthorizing and repurposing the Denali Commission—as AFN suggested in a March 2015 letter to the commission—as the lead federal agency for community and infrastructure resilience and relocation planning in rural Alaska. Designating the Denali Commission to play this role would help communities that face imminent threat of disaster move out of harm’s way.

3. Increase access to clean energy in Arctic communities

The president also could announce new initiatives to support hybrid energy systems in rural Alaskan communities. These systems integrate a mix of renewable energy resources—such as wind, solar, and hydropower—with existing diesel generators. The president also could expand support to improve the energy efficiency of rural Alaskan schools, buildings, and homes. These initiatives would strengthen community resilience by substantially lowering household energy costs—which exceed 50 percent of household income in some cases—as well as improve public health and reduce carbon dioxide and black carbon pollution in the region.

Lastly, the president could urge the U.S. Department of Energy to partner with Alaska to make it a major national test lab for innovative clean energy technologies. Such a partnership would also allow it to contract and compact with Alaska Natives to design, implement, and monitor renewable energy systems.

Conclusion

Together, the actions outlined above would help the federal government meet its trust responsibility to protect tribal treaty rights, lands, assets, and resources. These recommended actions would also help native communities avoid climate catastrophe, direct their own destinies, and thrive in a rapidly changing climate.

Cathleen Kelly is a Senior Fellow with the Energy Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Hannah Flesch was an intern with the Energy Policy team.

Thanks to Miranda Peterson, Erik Stegman, Danielle Baussan, Julie Kitka, Chris Rose, Jessica Grannis, Meredith Lukow, and Meghan Miller for their contributions.