Headlines can be deceiving. Following the January release of the Obama administration’s draft Five-Year Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program, a scan of news articles could easily lead readers to the conclusion that the president has opted to shut down offshore drilling in the Arctic while opening it off the Atlantic coast. Consider the following examples:

It is easy to understand why some readers assume that the administration has traded Alaska oil production for new drilling in the Atlantic. But in reality, the draft program—which outlines proposed management of offshore oil and gas leasing on America’s Outer Continental Shelf, or OCS, from 2017 to 2022—actually includes new lease sales in both regions. This is a tough pill to swallow for environmentalists, fishermen, and other industries that rely on healthy oceans.

The administration tempered the release of its five-year program with a couple of sweeteners. First, three days before the release of the draft plan, President Barack Obama asked Congress to designate an additional 12.3 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, including the coastal plain, as “wilderness”—a move that more than doubled the size of the area that had already been off limits to future oil and gas development. While Congress is unlikely to honor the president’s request, the Department of the Interior will treat the area as off limits until either the law or executive leadership has changed.

Second, the president announced that he would exercise his authority to make three new areas of the Arctic permanently off limits to drilling—a follow-up decision to his December 2014 move to safeguard Alaska’s Bristol Bay, one of America’s richest fishing grounds.

To help cut through the confusing rhetoric and see what the draft program would actually do, below is an overview of what it means for the Atlantic and Arctic oceans, as well as recommendations for what areas should be minimized or eliminated before the next five-year leasing plan is finalized. According to conversations with Obama administration officials, key point to understand about the draft is that the areas and total number of lease sales proposed cannot be expanded in the final version of the five-year program, but they can be reduced.

Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf

In recent years, momentum has been building to explore and potentially develop the oil and gas resources of the South Atlantic OCS. The current governors of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia now all support opening federal waters off their states to such activity. Meanwhile, elected officials from Maryland to Massachusetts have publicly opposed this latest effort to tap the Atlantic seabed. Their stance is bolstered by stalwart opposition from commercial and recreational fishermen, tourism-based businesses, and environmental groups. Even some municipalities have weighed in against the proposal: The Beaufort, South Carolina, City Council voted earlier this week to “be on record saying [oil drilling] is not appropriate for our coast.”

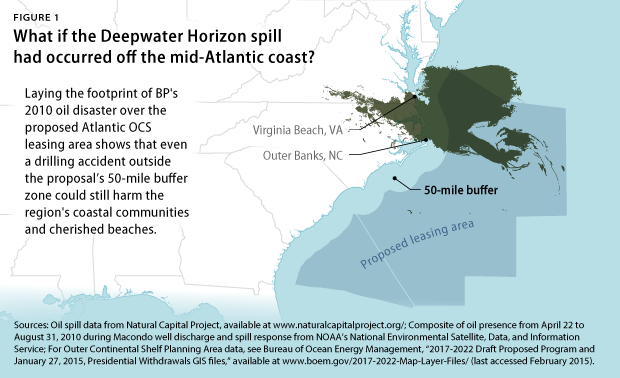

According to the National Ocean Economics Program, in 2011, fisheries activity and ocean tourism and recreation added more than $40 billion to the mid-Atlantic and southeast states’ gross domestic product, or GDP, and employed more than 750,000 people. Oil exploration and production put these key economic drivers at risk, as Gulf Coast residents learned so painfully during the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010.

Under the proposed draft program, any Atlantic Ocean leasing could only occur beyond 50 miles from shore. However, that buffer does not satisfy drilling opponents such as Sen. Ben Cardin (D-MD), and rightly so. As Sen. Cardin has pointed out, “oil spills do not respect state boundaries.” Indeed, ocean currents carried oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill hundreds of miles across beaches and marshes from Louisiana to Florida. The location of the powerful Gulf Stream current along the eastern seaboard means a spill in the Atlantic could contaminate coastal lands, estuaries, and waters far beyond the boundaries of the lease area.

Given the economic and environmental risks to the eastern seaboard, no oil exploration or production should be permitted along the U.S. Atlantic coast. If the final plan does include lease sales in the Atlantic, however, aspiring drillers must be forced to prove that their activities will not harm existing users or protected wildlife. Furthermore, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management must prioritize continued development of offshore wind farms without allowing offshore oil-development activity to impinge on a clean energy sector that, according to a report from the conservation group Oceana, would provide twice as many new jobs as fossil-fuel production.

Arctic Outer Continental Shelf

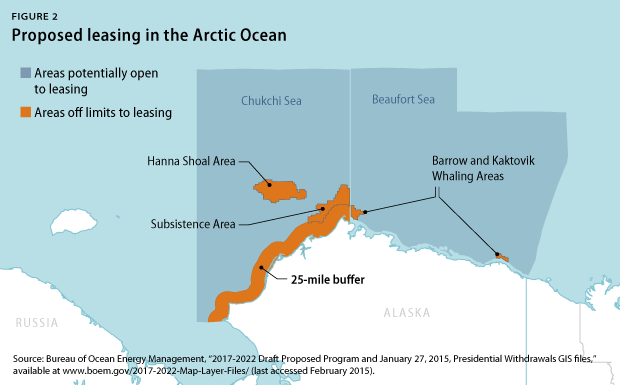

Although the draft program and affiliated executive actions in Alaska have drawn significant fire from drilling advocates, particularly in the Alaska congressional delegation, the reality is far less restrictive than they portray. The current proposals would leave more than 92 percent of the U.S. Arctic Ocean open to oil and gas leasing.* This fact exposes the stark hyperbole of Sen. Lisa Murkowski’s (R-AK) accusations, including that “this administration is willing to negotiate with Iran, but not Alaska.”

Even after permanently setting aside the three new areas—two areas vital to native Alaskan subsistence whaling and a more distant offshore area that encompasses critical habitat for walruses and other marine mammals (see map)—the draft program would still leave oil companies with access to 20 billion barrels of technically recoverable oil. The draft program also calls for two new lease sales.

Correction, February 13, 2015: Figure 2 was edited to clarify areas potentially open for OCS leasing and those withdrawn from the planning area through presidential action.

While the retreat of polar ice caps has opened the Arctic Ocean to increasing amounts of ship traffic and industrial activity, the 2012 Center for American Progress report “Putting a Freeze on Arctic Ocean Drilling” details the stark lack of response capacity and basic infrastructure that would be required to handle any kind of spill or other accident in the area. Any increase in oil and gas activity in the remote and virtually unpopulated Arctic represents a massive logistical challenge to both regulators and oil companies—and simply too much risk for the federal government to bear.

Current leaseholders have either opted not to operate in their lease areas or have struggled mightily in their efforts to explore potential reserves. In 2013, for instance, ConocoPhillips suspended its plans to drill in the Arctic Ocean. Its announcement came on the heels of Royal Dutch Shell’s dismal yearlong attempt to tap its leases, which forced the company to take at least a two-year hiatus from additional efforts to drill. This year, Shell announced its intent to return to drill the wells it began in the Arctic in 2012. This will push the company’s investment in the region north of $7 billion—with nary a drop of oil to show for that effort to date.

Including two new Arctic Ocean lease sales in this draft program is a dire mistake. The Department of the Interior must not allow any additional oil and gas exploration in the Arctic Ocean until the dramatic lack of infrastructure and oil spill response capacity is sufficiently addressed.

Looking ahead

Efforts to combat some of President Obama’s proposals have already begun. Sen. Murkowski, who chairs the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, has led efforts to roll back executive authority to designate national monuments. On February 10, she introduced legislation—co-sponsored by her new colleague Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK)—that would require Congress to approve any new national monument designations. The bill would effectively nullify an executive power that was first granted by the American Antiquities Act of 1906 and that has led to the establishment of some of our nation’s most treasured places.

Meanwhile, lawmakers on the Atlantic coast have expressed a desire for their states to receive direct revenue from offshore leases. On the day the draft program was released, Virginia’s two Democratic senators, Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, released a statement that referenced their legislation from the last Congress that would grant a portion of offshore leasing royalties to Virginia. And Sen. Murkowski was the lead co-sponsor of legislation introduced by former Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-LA) that would have vastly expanded existing revenue-sharing efforts in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska. Additional effort on revenue sharing should also be considered a given in the 114th Congress.

The Obama administration has a difficult task ahead as it attempts to develop a strategy for fossil-fuel production on the Outer Continental Shelf while also pursuing its ongoing agenda of combating climate change. Striking a reasonable balance may end up being far more difficult than striking oil in the remote and ice-choked waters of the Alaskan Arctic.

Michael Conathan is the Director of Ocean Policy at the Center for American Progress. Shiva Polefka, a Policy Analyst at the Center, contributed to this column.

* The 92 percent figure was established by comparing the 127.67 million acres of total leasing area in the 2012–2017 Five-Year Leasing Program—62.59 million acres in the Chukchi Sea and 65.08 million acres in the Beaufort Sea—to the 9.8 million acres withdrawn from consideration by executive action on January 27.