Higher education has long been a path to economic security, and this is especially true for low-income students, first-generation college students, and students of color. Current demographic trends show that non-Hispanic whites will no longer comprise a majority of the U.S. population by 2050, when they will make up just 47 percent of the population. Already, half of all U.S. births are children of color. At the same time, middle-class earnings have stagnated, and poverty is becoming more widespread. As the population continues to change, it is increasingly important to future economic security that degree-attainment rates reflect the nation’s changing demographics.

The nation’s public universities—a key vehicle of upward mobility—must do more to even the playing field for all students. As it currently stands, students from the least advantaged populations earn degrees at a lower rate and are burdened with a greater portion of debt than their peers. However, some standout public universities are reversing these trends by committing to need-based funding, offering successful student support programs, and providing institutional leadership. As both communities of color and the poverty rate continue to grow, it is economically imperative to improve the value of college for the least advantaged students.

Unequal degree attainment and higher debt

While access to higher education has increased overall, students of color and low-income students experience higher student loans and time-to-degree levels and lower degree attainment than their peers.

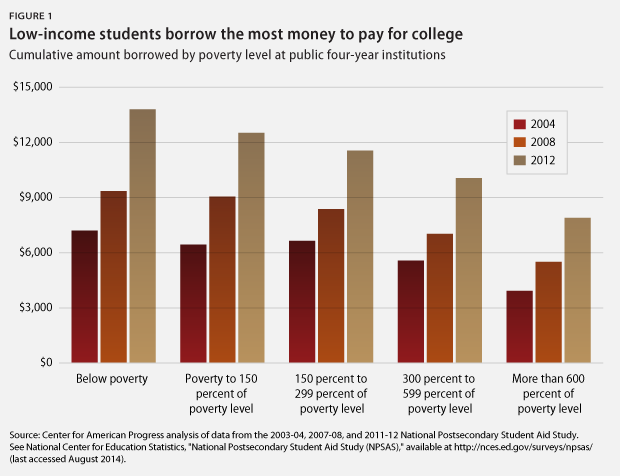

Students from families at or below the federal poverty level lack financial resources and, on average, borrow the most to pay for college. Despite dramatic increases in funding for the need-based federal Pell Grant program in recent years, declining state investment in higher education—another important source of need-based aid and institutional revenue—has made college less affordable, particularly for lower-income families. The ensuing increases in tuition and fees have decreased the share of tuition covered by Pell Grants, leaving students with a higher degree of unmet financial need. In other words, college is becoming less affordable for the population with the greatest need for a path to the middle class. At public four-year institutions, students from the lowest income group need to borrow almost twice as much as students from the highest income group to fund their education. This disproportionately affects students of color, since blacks and Latinos are more likely to fall in lower income categories than whites.

Furthermore, students of color, first-generation college students, and low-income students take longer to graduate, which increases borrowing across their academic careers. At public four-year institutions, 61 percent of incoming white, first-time students attain a bachelor’s degree in five years, compared with just 46 percent of black students and 49 percent of Latinos. Black and Latino students are also more likely to leave school without completing a degree, with more debt, and—presumably—without the reward of increased earnings in the workplace. Similarly, students from the lowest income group are 30 percent less likely to attain a bachelor’s degree in five years than the highest income group and are almost three times more likely to leave without a degree. This affects students’ incomes for the rest of their lives: A working adult with a bachelor’s degree earns an average of $18,000 more per year than an adult worker with only some college education.

In other words, the populations with the greatest need are burdened with high levels of debt without the promise of a degree. Given projected demographic changes in the United States, public universities must do a better job of graduating all students at a lower cost.

Public universities that defy the odds

Despite these disheartening statistics, some universities have successfully closed graduation gaps across demographic groups while raising their percentage of low-income students, achieving increases in both access and equal degree attainment. This issue brief examines three such universities—the University of California, Riverside, or UCR; the University of South Florida Tampa campus, or USF; and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, or UNCC—and assesses some of the policies behind their positive outcomes. Sustained university-wide commitments to the success of all students and to the provision of need-based aid and student support programs have helped accomplish this goal.

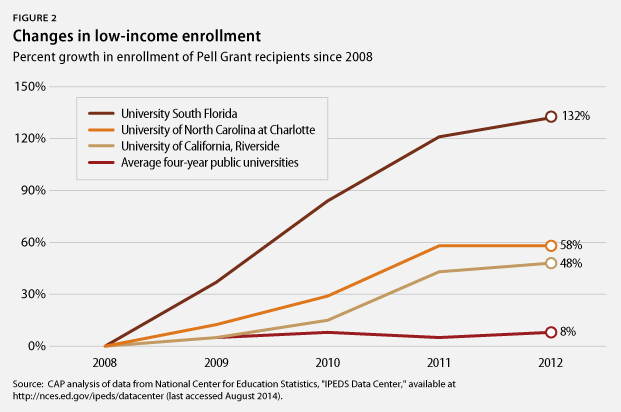

Across all four-year public universities, a median of 40 percent of students received Pell Grants in 2012—an increase of just 8 percent since 2008. In contrast, the three high-performing universities discussed below have all increased their percentages of Pell Grant recipients at significantly higher rates over the same period: UCR increased enrollment of Pell Grant recipients by 48 percent, to 59 percent of total enrollment; USF’s share increased by 132 percent, to 44 percent of total enrollment; and UNCC’s share increased by 58 percent, to 38 percent of total enrollment.

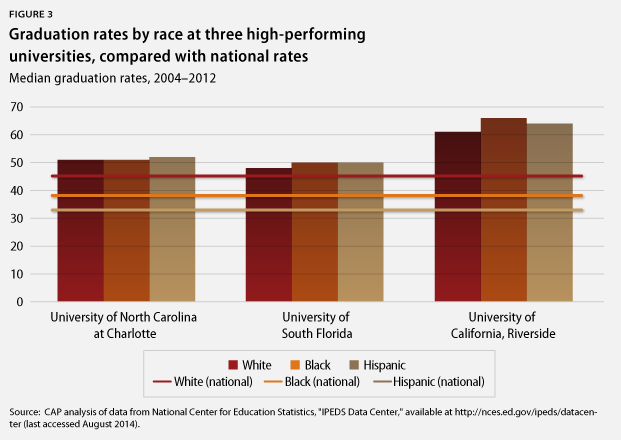

Additionally, each university has maintained a graduation gap across demographic groups that is near or below zero. Nationally, from 2004 to 2012, incoming white students at four-year public universities were an average of 12 percent more likely to graduate than black students and 7 percent more likely to graduate than Latino students. However, at UCR, black and Latino graduation rates were 6 percent and 3 percent higher, respectively, than white graduation rates. At USF, the graduation rate for both black and Latino students was approximately 2 percent higher than that of white students. The average graduation rate at UNCC was approximately 51 percent across all racial groups. These three successful universities have minimized graduation gaps across demographics while also increasing overall graduation rates.

Based on interviews with relevant staff from each university, this issue brief details some of the actions behind the positive results.

Commitment to need-based funding at the federal, state, and institutional levels

All three high-performing universities indicated that a mix of federal, state, and institutional financial support was crucial to increasing access and degree attainment for low-income students and students of color.

A commitment to providing need-based funding was one of the top reasons cited for USF’s improved graduation rates, decreased graduation gaps, and increased enrollment of Pell Grant recipients. USF has doubled its share of Pell Grant-eligible students and increased graduation rates by 10 percent since 2008—changes that came after the university led a Student Success Task Force to address student retention, graduation rates, and financial indebtedness.

Recruiting college-ready students who are also first-generation college students, have limited incomes, and/or are students of color requires an institutional investment to increasing student funding, according to Vice Provost for Student Success Paul Dosal, who spearheaded the USF task force. Billie Jo Hamilton, assistant vice president for enrollment and planning management, added that USF has made a concerted effort to distribute its limited need-based grant money in a way that at least covers students’ direct costs, including tuition and fees, room and board, and books. Despite tuition increases, USF has tried to increase need-based financial aid to offset costs for its neediest students. The Florida state legislature mandated that public universities must use 30 percent of tuition money for need-based aid, but USF President Judy Genshaft decided to increase that funding level to 40 percent. In addition, USF has also used tuition revenue to increase merit-based scholarships.

At UCR, 59 percent of the student body is eligible for the Pell Grant program and 60 percent are first-generation college students. According to Assistant Provost Bill Kidder, a high level of financial support was an important component of these outcomes, and the university “puts its dollars where its values are.” The University of California, or UC, system’s need-based aid pool is several times larger than the value of the Pell Grants received by its students. Kidder says that “the large institutional commitment from the UC basically means making choices about directing undergraduate student tuition to low-income students.” California students are also eligible for the need-based Cal Grant program. These three sources of aid provide a robust infrastructure of support for low-income students, which Kidder says has contributed to higher enrollment of low-income students at UCR and across the UC system. The aid support has also translated into degree attainment: UCR’s Pell Grant recipients graduate at the same rate as high-income students, a trend that has held across several cohorts of freshmen.

While UNCC did not explicitly point to need-based aid as a strategy to improve graduation rates, Director of Financial Aid Bruce Blackmon indicated that it is important to students. In addition to the federal Pell Grant, North Carolina provides two separate funds—the North Carolina Education Lottery Scholarship and the UNC Need Based Scholarship—for students whose incomes are barely eligible or just above eligibility for Pell Grants. The North Carolina state legislature also mandated that some student-fee revenue must go to an in-house tuition-assistance grant. UNCC targets those funds based on unmet need for each incoming class and awards aid based on a matrix that targets all students until the money runs out. Although there is never enough to fund everyone, the combination of Pell Grants, state grants, institutional funding, and subsidized loans brings most students within the range of affordability.

While this financial support is critical to improve higher-education access for low-income students and students of color, decreasing state funding for public universities has led to equal increases in tuition. All three universities discussed above are in states that have cut higher-education funding since 2008. For example, Florida halved its main merit-based scholarship, Bright Futures, for the 2014–15 school year. USF Vice Provost Dosal worries that these cuts will affect the high-ability, low-income students who rely on the Bright Futures scholarship as much as the Pell Grant. USF has tried to adjust funding to make up for the gap but has been unable to do so. If Pell Grant funding is also cut, Dosal says, USF would be unable to support the academic progress of its students—particularly those who are most needy. According to Hamilton, replacing a grant with a loan for low-income students would potentially limit access and prevent low-income students from attending college.

Amid a climate of state funding cuts and rising tuition, access to need-based aid is necessary to stem the growing burden of debt on the students with the least financial resources. As all three schools have indicated, state funding toward need-based grants—in addition to state laws on the percentage of tuition that is used for need-based aid—is crucial to improve outcomes.

Student support

Aside from need-based aid, high-performing universities credited numerous student support services—programs aimed at improving student performance and attainment—with increasing graduation rates and closing graduation gaps. Earlier U.S. Department of Education evaluations of the Student Support Services program—one of eight grant programs under the federal TRIO programs—found that programs such as labs, tutoring, and workshops improved academic retention and graduation. Many of the support services in this issue brief were targeted at incoming freshmen. Offering support to students—particularly low-income students, first-generation college students, and students of color—as soon as possible is critical to retention and degree attainment.

Summer bridge

All three universities in this brief credit summer bridge programs—accelerated summer programs targeted toward incoming students who are underprepared for fall courses—with helping these students succeed. Numerous studies have shown that summer bridge programs improve enrollment, retention, and student satisfaction rates.

UNCC has the longest-standing program—the University Transition Opportunities Program, or UTOP, now in its 28th year of existence. The program involves incoming freshmen from underrepresented groups in a rigorous six-week college experience. UTOP participants’ first-to-second-year retention rate is 12 percent higher than that of all other first-time college students at UNCC, and they have a higher graduation rate as well. The Freshman Summer Institute, USF’s summer bridge program—aimed at first-generation college students and limited-income families—has also been successful. Participants’ early advantage has led to a 90 percent first-to-second-year retention rate, compared with 81 percent for all students. UCR’s Summer Bridge program for low-income, Hispanic, and transfer students seeks to help students catch up in core subjects and familiarize them with university services.

First-year transition programs

All three universities also frequently credited support during a student’s first year with increasing his or her success. Previous Center for American Progress research found that the use of learning communities—groups of students with shared values who actively engage in learning together—could improve outcomes for students, particularly for institutions that serve high percentages of students of color. The evidence provided by the universities support this claim.

At USF, the student support initiative looked closely at potential barriers to students’ academic progress and recommended instituting a professional advising system and increasing the number of advisors. The 2009 student success task force also identified first-year programs and orientation as one of the areas in need of improvement. The university focused on the range of students’ entry points to set them on the right path from their first moments on campus. This meant requiring freshmen to live on campus, improving opportunities for on-campus employment, and encouraging students to be involved and engaged. According to Vice Provost Dosal, these kinds of supports could easily be implemented at other institutions at a cost that certainly would be worth the improved outcomes, given adequate financial support and institutional commitment.

UCR points to its large supplemental learning program that assists students who arrive on campus less academically prepared than others as an important contributor to its success. UCR also mentioned its first-year Learning Communities program that focuses specifically on science majors and offers increased access to low-income, first-generation college, and underrepresented students. The approach is increasing retention rates in the science, technology, engineering, and math, or STEM, majors and yielding graduation rates of 55 percent to 65 percent, compared with the national average of 40 percent for STEM majors. The supplemental learning program and first-year learning communities help give students from underserved backgrounds a fair chance.

UNCC Provost Joan Lorden also indicated that the transition from high school to college is particularly important for first-generation college students, and in addition to the UTOP program, the university offers learning communities by major and freshmen-specific seminars. Lorden points to UNCC’s unique history as one of the reasons why it has enjoyed such success. The school started as a two-year community college and transitioned to a four-year community college in the 1960s. Two-year community colleges are much more likely to enroll underserved populations, students of color, and lower-income students than four-year universities. As such, they are accustomed to meeting the special needs of these populations. Given this history, UNCC enrolls about the same number of transfer students and new freshmen each year, many of whom are from community colleges. This makes the university’s success even more impressive, since students from community colleges are much less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree.

Diverse student populations

To provide the greatest degree of student support, it is important for administrators to understand the student body and the needs of the various populations within it. With respect to race and ethnicity, UCR Assistant Provost Kidder points to “critical mass” as an important factor in students’ overall success, in addition to providing a welcoming environment and setting high expectations for all students:

On some other campuses, if African American students are a small percentage of the student body, they see that when they walk across campus and feel it in the classroom, which can be a contributing factor to decreased success, whereas at UCR, there is more of a critical mass, a circumstance where success begets more success.

At UCR, he says, academic excellence and diversity support each other.

USF is implementing an analytics platform that will allow it to identify barriers unique to particular groups of students and to identify solutions to ensure their success. However, in a time of declining higher-education funding, universities often have to make trade-offs. At USF, for example, a decline in state funding prevented the school from improving its faculty-to-student ratio. Adequate funding is required to effectively support the programs and the staff required to run them.

Public universities often explain disparities in student performance as a result of differences in income, academic preparation, and the cultural capital of students. These examples show that targeting programs to address such different populations’ needs can change and even equalize student success regardless of student background.

Institutional leadership

Lastly, representatives from all three high-performing universities included in this brief emphasized leadership as an important factor in improving retention and graduation rates for underserved populations. USF Vice Provost Dosal said that the changes stemmed from President Genshaft’s determination to raise the academic profile of incoming students and willingness to put money where it was needed. Dosal stated that this was certainly the first step, but an overall institutional commitment must follow.

UCR Assistant Provost Kidder also pointed to the importance of an institutional commitment to supporting low-income students and students of color. For UCR and institutions across the UC system, that means committing to high expectations for all students, working tirelessly to create an overall positive environment, and “having a campus climate where African American and Latino students, for example, feel welcome and respected on campus.” He cites his own research, which showed that African Americans felt more respected on UCR’s campus compared with students at other research universities.

Provost Lorden said that the most important part of UNCC’s success was having staff members who care and are committed to the success of all their students. UNCC has a high number of Pell Grant recipients, students with high financial need, and first-generation college students, so it devotes quite a lot of energy to student success overall, in addition to having specific programs for underrepresented students.

While many public universities offer robust need-based aid programs and student support services, it is strong leadership and institutional commitments to improvement that ultimately make these three universities stand out.

Conclusion

High-performing public universities play a critical role in providing a path to the middle class. Too often, however, these institutions are plagued by low retention and graduation rates—particularly for the neediest students. The examples of USF, UCR, and UNCC show that increasing access to underserved populations while improving graduation rates and reducing graduation gaps across demographics can be accomplished with the right balance of federal, state, and institutional support.

A previous CAP report titled “Public College Quality Compact for Students and Taxpayers” detailed how decreased state investment in higher education has led to decreased affordability and higher borrowing for students. As discussed here, this burden of borrowing is falling on the students with the greatest need and is limiting access to higher education and—ultimately—to the middle class. The report called for increasing student support through a combination of federal Pell Grants and state funding. Increasing student performance requires making hard choices about where to direct funding. As these case studies make clear, need-based aid and student support are worthwhile investments in student outcomes, and institutional leadership and support are imperative to successful implementation.

Antoinette Flores is a Policy Analyst on the Postsecondary Education Policy team at the Center for American Progress.