See also: “Graduate School Debt: Ideas for Reducing the $37 Billion in Annual Student Loans That No One Is Talking About” by Ben Miller

There’s a gaping hole in existing discussions of federal student loans: debt from graduate school.

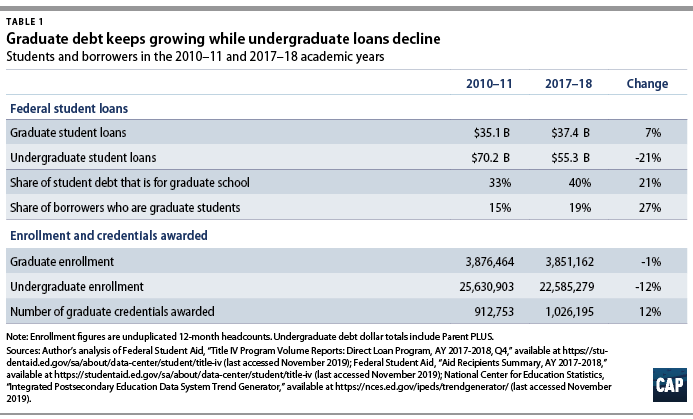

- Graduate borrowing amounts to more than $37 billion in loans annually and accounts for 40 percent of federal student loans issued each year.

- Graduate debt keeps growing even as undergraduate borrowing falls.

- While graduate borrowers have much lower estimated default rates than undergraduate borrowers, they are much more likely to use income-driven repayment (IDR) plans. More than 40 percent of loan balances that amount to more than $60,000—which are most likely held by graduate borrowers—are now being repaid using IDR. Although these plans can help borrowers, they extend repayment time frames and can result in high interest accumulation.

The equity implications of graduate debt are serious too:

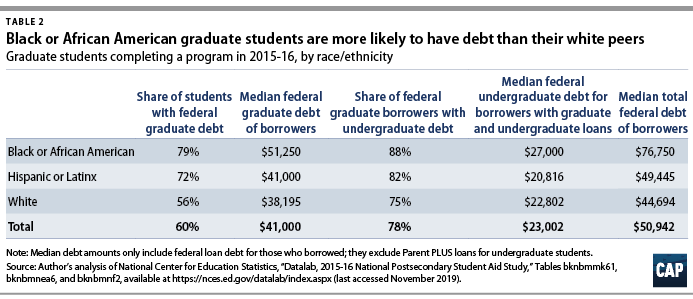

- Black graduate students are more than 20 percentage points more likely to borrow than their white peers, and their typical debt levels are $25,000 higher.

- Latinx graduate students are 16 percentage points more likely to have graduate debt than their white counterparts, and they end up with nearly $5,000 more in debt.

- Black students in research- and scholarship-based doctorates were half as likely as their white peers to receive fellowships or assistantships in the 2015-16 academic year.

Solutions for graduate debt

Solutions for graduate debt

It is time for the federal government to play a more active role in bringing down graduate debt levels. To spark this conversation, the Center for American Progress considers six accountability-based solutions for addressing this problem. These solutions are not meant to be independent of or supplant broader reforms such as major new investments in college affordability, student debt cancellation, or reinstating the Obama-era gainful employment rule.

The solutions also consider a longer time horizon than ongoing debates around the Higher Education Act’s reauthorization. CAP does not explicitly endorse any of these ideas and notes that there would need to be careful attention paid to avoid any unintended equity consequences. The potential solutions include:

- Judge graduate programs on a debt-to-earnings rate to ensure that they do not force students to borrow more than they can afford. This must be done separately from and after efforts to restore the gainful employment regulation and is by no means an endorsement of extending gainful employment to all postsecondary programs.

- Hold programs accountable for repayment rates or excessive reliance on IDR plans. Policymakers could enact a repayment regime and make changes to interest accumulation on IDR. Whether capping debt or requiring risk-sharing payments, programs should be held accountable if their students are too reliant on IDR.

- Create dollar-based caps on graduate loans but do so in a way that does not require reducing spending elsewhere. This is opposed to existing policy, which allows students to borrow up to the cost of attendance set by the institution.

- Ban balance billing. Policymakers could adopt a concept from health care that prevents charging consumers an amount beyond what federal aid and a reasonable student contribution allows. This would require work to separate living expenses from direct academic charges.

- Institute price caps. Policymakers could adopt ideas from other areas that require programs to cap their rate of price growth, establish a reference price so consumers know if they are picking an overly expensive option, or set an explicit cap on how much can be charged for a given program.

- Tackle specific credentials. Instead of broad-based solutions, policymakers could address individual degrees such as:

- Master’s degree in education, teaching, or social work: Require them to be affordable based on likely earnings if students are required to work.

- Law school: Move to a two-year instead of a three-year credential.

- Medical and dental school: Fund more spots upfront and improve equity by expanding the National Health Service Corps.

- Research-based doctoral degrees: Create requirements for institutional funding to ensure students are not forced into excessive debt levels. This would also correct unacceptably low rates in assistantships and fellowships for Black students.

Viviann Anguiano is an associate director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress. Ben Miller is the vice president for Postsecondary Education at the Center.