This report contains a correction.

Introduction and summary

The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) has become a ubiquitous part of the college-going process. In 2017, 17 million students completed the form, receiving more than $122 billion in federal student aid.1 While the FAFSA provides access to college financing for millions, it often comes at a price, representing one of the many hurdles students must overcome before they even step foot in a college classroom.

The FAFSA has been around for almost 30 years, changing over time to reflect politics, national priorities, technological innovations, and the composition of the student population. For example, in 2004 it was made available in Spanish to accommodate a growing population of Latinx students.2 What has not changed, however, is the reality that the form has never been easy to complete. It has more than 100 questions, many of which ask detailed information about income and assets that can only be answered by plumbing tax return data.

While the FAFSA allows all students to access loans, it is particularly vital for low-income students to complete the form, as it provides them with access to the federal Pell Grant. This aid, which totals $6,095 in the 2018-19 school year, can mean the difference between enrolling and forgoing a college education. Research shows that hundreds of thousands of low-income students are tripped up by the form each year, failing to complete the application and verify their information as the first day of class approaches.3 For many, this means their chances of enrolling in college, let alone completing, are slim.

Over the past decade, policymakers on both sides of the aisle have singled out the FAFSA for reform, often noting the cumbersomeness of the process.4 In particular, Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN), the current chair of the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and the former secretary of education under President George H. W. Bush, has turned the FAFSA into a frequent prop, unfurling a paper form on more than one occasion, the pages trailing down to the floor.5 While he has pushed to make the FAFSA a two-question form that could fit on a postcard, the U.S. Department of Education has taken more modest steps, implementing changes that allow families to skip questions that do not apply to them and import their tax data directly from the IRS.6

While shortening the FAFSA is a worthy effort, it fails to address another key way the form can burden families: its frequency. Students receiving federal aid must complete the FAFSA each year, a process that represents a significant investment of time and resources for families, institutions, and the federal government—regardless of its length.

An annual FAFSA can create three issues for students. First, students may be required to go through a significant amount of unnecessary paperwork in order to receive the exact same aid they received the year prior. Second, they may take annual reapplication as a signal that their aid is not stable, leading them to question if they can afford to complete a degree. Finally, an annual FAFSA opens up opportunities for students to miss deadlines, putting their aid in jeopardy.

For colleges and the federal government, an annual FAFSA means a lot of resources spent processing forms, correcting errors, and answering questions. Were annual renewal not required, the government could better direct these federal expenditures to need-based aid and institutional support, and college administrators could instead spend time providing meaningful financial aid counseling to students.

With college students citing finances as the top reason for dropping out of school,7 it is worth asking if the FAFSA requires an unnecessary level of year-to-year precision in calculating a family’s ability to pay for a college education. Instead, could students complete the FAFSA once, when they first enroll in college? A one-time FAFSA would greatly simplify the aid application process while balancing the desire of the federal government and colleges to collect information they deem necessary to award aid. In the end, students could be guaranteed a simpler process and more stable financial aid.

This idea is not a new one. Researchers Sara Goldrick-Rab and Robert Kelchen called for a one-time FAFSA in 2013,8 noting the harm FAFSA renewal can cause low-income students. A few years later, Democrats on the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce proposed the File Once FAFSA Act of 2016 but limited the legislation to dependent students whose incomes are low enough to make them eligible for a Pell Grant. Though this policy could have a positive impact, it leaves out independent students, who comprise half of the undergraduate population and almost 60 percent of Pell Grant recipients.9

To determine if a one-time FAFSA could be implemented and who it would most help, the Center for American Progress worked with 27 colleges around the United States to gather data for nearly a quarter of a million students who filled out the FAFSA at least two times. The analyses of these data focus on how much students’ expected family contribution (EFC) figure varies from the first year they filed and seek to understand the causes of larger variations in EFC.

The results show that for half of all students in the study who applied for aid, EFCs changed by $500 or less for the duration of these students’ enrollment. EFCs were even more stable among specific populations who were most likely to receive need-based grant aid such as Pell Grants, 70 percent of whom saw an EFC change of only $500 or less. The picture looks similar for independent students, who are largely adults. Sixty-eight percent of independent students saw an EFC change of $500 or less while enrolled. Students with dependents of their own were even more likely to have stable EFCs: Three-quarters saw no change in their EFCs while they were enrolled.

In fact, the students most likely to see a significant EFC change started college with an EFC too high to qualify for need-based federal aid, such as Pell Grants. For them, the FAFSA may be capturing EFC changes that have no bearing on the amount of federal grant aid they receive. These students may have only completed the FAFSA to receive federal student loans that are not awarded based upon financial need or to seek state or institutional assistance.

These findings suggest that a one-time FAFSA could be implemented for all students, which would yield universal benefits to students and colleges. Communication of the policy would be clear, and everyone who interacts with the form would experience a reduction in burden. Although a one-time FAFSA could be targeted to low-income or independent students, as they have the most stable EFCs, doing so would cut into the benefits of the policy and create confusion for students. If policymakers want to think big about simplifying aid, they must see the bigger picture—not just focusing on questions, but also on the form as a whole.

Financial aid and the role of the FAFSA

Each year, the federal government provides more than $122 billion in aid to undergraduate students. In 2017, that represented $27.7 billion in Pell Grants, Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants, and other gift aid; $949 million in the federal work-study program; and $93.8 billion in federal direct and Perkins loans.10 Many of these programs, including all grant and work-study funds, are allocated to students based on their financial need.

The federal government determines who has financial need by calculating the annual EFC for every student who applies for financial aid. The EFC is derived from information submitted on the FAFSA. The form collects information on a prospective student’s demographic characteristics, such as their age and gender, as well as data related to a student’s family size and composition, income, assets, federal means-tested benefits received, military service, and savings. All of these figures are inputted into a complex series of formulas known as need analysis, which determines the amount of assets and income that a family can put toward college.

The EFC determines whether a student is eligible for financial aid and, if so, the maximum amount they can receive from the federal government in a given year. For example, if a student has an EFC of $0, then they are eligible for the maximum Pell Grant, which is currently $6,095 a year. If a student’s EFC is $1,950, then they are only eligible for $4,145 from the Pell program.11 By contrast, if a student’s EFC is $19,500, then they are not eligible for need-based grant aid.

Despite its name, the EFC does not dictate what a family is expected to pay for college; it is not binding on the student or institution. Thus, if a student with a $0 EFC only receives $6,000 in grant aid but faces a price tag of $10,000, the student is expected to make up that $4,000 difference through other means. Effectively, the EFC acts as an eligibility indicator for need-based aid programs rather than a cost estimate upon which families can rely. Unfortunately, this plays out worst for the lowest-income students; in 2016, students with a $0 EFC faced college costs that totaled, on average, 70 percent of their income.12

The FAFSA is not only responsible for providing federal grants; it is also often used to determine who receives state and institutional grants. At least 35 states and one U.S. territory13 use FAFSA data to determine a student’s eligibility for need-based grants, which totaled nearly $9 billion in 2015.14 Colleges also use the FAFSA to better understand student’s financial situations and, often, the amount of institutional grant aid that they will receive. In the 2015-16 school year, college grant aid totaled more than $11 billion for first-time, full-time college students, though it is difficult to know how much of that aid was awarded on the basis of need and was based on data from the FAFSA rather than other aid application forms.15

Brief history of the FAFSA and recent reform efforts

Congress created the FAFSA in 1992 as part of an effort to use a single form and eligibility calculation to award all need-based federal financial aid.16 Prior to the FAFSA, the federal government had two separate aid formulas: one for Pell Grants and one for all other types of need-based aid.17 The 1992 law made the FAFSA the only form students could use to receive any federal financial aid, as well as the only form schools can use to award it.18

In its nearly 30 years of existence, the FAFSA’s need analysis methodology has evolved, with some questions added to exclude certain groups of students, such as those with drug convictions, from receiving aid and others—such as questions about dislocated workers and students in legal guardianship—to identify students who may be economically distressed.

Although the number of questions on the FAFSA has increased, the form has also become simpler to complete. The Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA), which administers the FAFSA, created an online version of the application in 1997,19 an update that opened the door for several simplifications. For example, in 2009, the FSA implemented additional skip logic in the online form, which allows students to automatically pass through portions of the form that are not relevant to them.20 FSA also partnered with the IRS in 2009,21 allowing families to automatically import correct tax data into the FAFSA form through the Data Retrieval Tool (DRT).

However, families still ran into significant timing-related issues when filing the FAFSA. In the past, the form was made available on January 1 of each year, and, facing early state and institutional aid deadlines, families would often scramble to submit the form with estimated tax data. Upon filing their taxes, families would have to refile the form with official tax data, then have to wait for financial aid offices to reprocess their applications and award their aid. All this meant that students too often had little time to consider their aid packages before committing to a college, and colleges and families were forced through a duplicative process that caused undue frustration and wasted resources.22

In response to these issues, the Department of Education implemented two major changes in 2015 that not only simplified FAFSA filing, but also altered the income information used for need analysis.23 Early FAFSA made the form available three months earlier, on October 1 instead of January 1 of the following year. The early availability date means that students can fill out the FAFSA while they are applying for college, rather than during the spring. This change was paired with new guidance that allows students to use income information from two years earlier to calculate their EFC, a policy commonly called prior-prior year (PPY).24 In the past, for example, the 2018 EFC was based on 2017 income information, but with PPY, families could use 2016 income information. Using PPY allows families who filed their taxes on time to complete the FAFSA and use the DRT as soon as it becomes available on October 1.

Combined, these changes allow colleges to provide financial aid information to students when they are admitted, rather than later in the spring, when students are under pressure to accept admissions offers. The FSA continues to experiment with new ways of making the FAFSA more accessible. In August 2018, it launched a mobile application that allows students to submit via a mobile device, in part to provide access to the form for students who may have trouble accessing a computer or the internet.

Challenges arising from an annual FAFSA

The FAFSA is a long-standing thorn in the side of students not just because of its complexity, but also because it must completed each year. Updated income, asset, and family size data are used to derive a new EFC, which can produce several issues.

First, there is the issue that some students are unaware of the need to file the form each year. Research has found that about 16 percent of first-year students who received a Pell Grant do not refile the FAFSA, and those students also have a high risk of not returning for a second year.25 Moreover, even if outreach campaigns reach these students, it can be too late. Several states and colleges have firm reapplication deadlines, and if aid is awarded on a first-come, first-served basis, students who file late may lose out on aid that they received the previous year.

Second, annual FAFSA renewal represents a significant burden for students whose EFCs may not change much, if at all. For example, a student could have a $0 EFC year after year, yet is still required to present information repeatedly proving their circumstances are the same. This represents not just a burden for the student, but also for aid offices, which must collect and process FAFSA data annually.

Third, annual FAFSA renewal costs institutions and the federal government significant resources. An estimate conducted by economists in 2008 conservatively placed the cost of FAFSA administration and compliance at $4 billion per year.26 This outlay of time and money can be better spent on additional funding for need-based grants or providing more time counseling students.

Finally, students may be required to go through the process of confirming their FAFSA data even after they submit the form correctly. This process, known as verification, can be onerous on students and financial aid offices, which must coordinate the verification of data. Students must submit additional documentation proving their income information, which can be particularly daunting for students and families who are not required to file income taxes due to their low-income status. Every year, the Department of Education selects up to 30 percent of students, but the burden is felt most by low-income students, about half of whom must complete verification to receive aid.27 Based on some estimates, up to 22 percent of Pell Grant-eligible students do not complete the aid application process due to verification.28 Were students required to do the FAFSA just once, they could be spared the burden of this process and have access to stable year-to-year aid.

The potential benefits of a one-time FAFSA

The FAFSA makes federal financial aid an inherently unstable source of financing for students, because they do not know if their EFC will remain the same from year to year and, thus, if they will receive the same aid each year. As college costs increase and policymakers turn their attention toward providing students with better access to affordable postsecondary options, many advocates, researchers, and policymakers have advocated for a simpler FAFSA application. But these discussions focus more on the number of questions on the form rather than the bigger picture: What if the federal government only required students to complete the FAFSA once?

To date, most simplification efforts have focused on drastically reducing the number of questions on the FAFSA. Sen. Alexander has even proposed a two-question form, which would only ask for family size and adjusted gross income.29 However, such shortened forms risk unintended consequences that could have deleterious effects on students. In an absence of more information, institutions or states could start requiring additional aid applications, which would do nothing to reduce the paperwork burden on students—and, for that matter, on institutions. It would also reduce the amount of information the federal government collects on students and families who use the aid program, which can provide valuable insight into the demographics of the college-going population and how it is changing.

A one-time FAFSA would remove much of the administrative hassle for students, colleges, and the federal government, as well as ensure that students receive consistent access to aid for the duration of their enrollment. This change represents an alternative to having a form that only asks a few questions and instead leaves in place the system that exists today. As an added bonus, savings from moving to a one-time FAFSA could be funneled into providing better supports for low-income and other underrepresented students.

Of course, there are a number of questions that arise with a one-time FAFSA. If students have relatively stable EFCs while enrolled, then a one-time FAFSA would not levy many, if any, costs to the federal government, states, or schools, as it would not make much difference in the year-to-year amounts that are awarded. But significant annual variation in EFCs would make the policy more challenging, because some students would receive too little aid based on their actual eligibility while others receive more.

To gauge the viability of a one-time FAFSA, this report uses data covering nearly a quarter of a million students to look at how much EFCs change over time. Though this sample is not nationally representative, it does provide a sizable base to see the extent to which EFCs change from year to year. The report also breaks down what factors cause EFCs to vary, which will help assess whether policy tweaks could solve some issues with a one-time FAFSA. Finally, this report concludes with a discussion of how a one-time FAFSA could be implemented, with a variety of options to target certain groups of students.

Data and methodology

The data used in this report were provided by 27 colleges that span the public two-year, public four-year, and private nonprofit four-year sectors. The analyses presented are based on FAFSA data from more than 236,000 students who completed more than one FAFSA between 2010 and 2017.30 These data allow calculations of how students’ EFCs vary over time from a their initial EFC upon enrollment and allow for additional exploration into what drives those changes.

This report provides an exploratory analysis of how EFCs change from year to year and investigates which groups of students are the most likely to have stable EFCs. The sample of students and colleges is not representative, so the findings in this report may not reflect the overall FAFSA-filing population. Should the federal government provide a more representative sample of data, these analyses can be replicated and built upon to determine the feasibility of a one-time FAFSA policy.

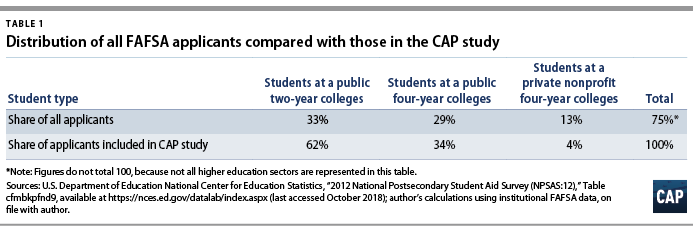

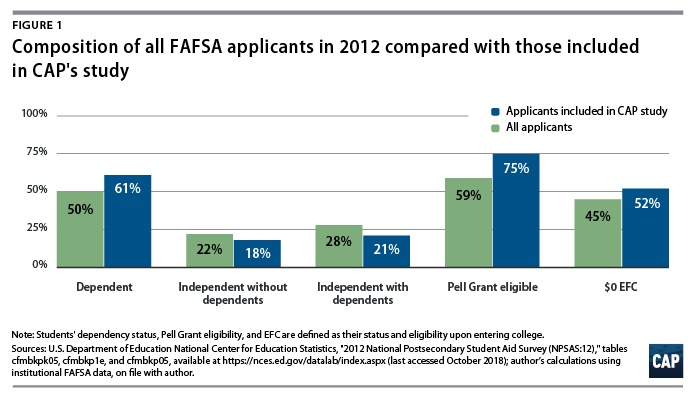

Tables 1 and Figure 1 identify how the colleges and students included in this study differ from the overall college-going population who applied for aid in 2012. Due to overrepresentation of community college students, there are more Pell Grant-eligible students in this study. Dependent students are overrepresented as well, likely because many of the public four-year colleges included are selective, thus they educate fewer independent students than do public regional comprehensive colleges.

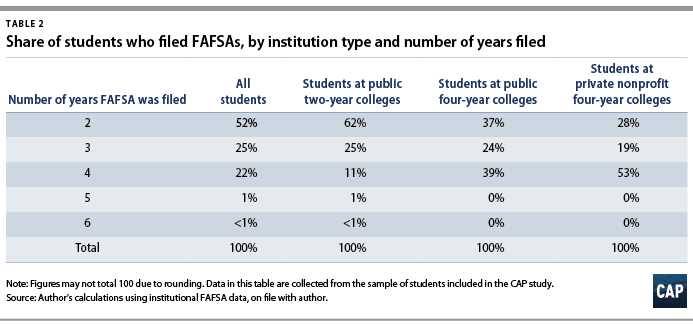

Half of students in the study completed FAFSAs for just two award years. It is difficult to know how this maps to the overall population of students, as similar data are not available. Table 2 shows that 62 percent of community college students completed just two FAFSAs, whereas 39 percent of public four-year students and 53 percent of private nonprofit four-year students completed four FAFSAs. These differences are likely tied to the nature of the programs offered by these schools, with four-year colleges offering predominantly bachelor’s degrees while community colleges offer more associate, certificate, and transfer programs.

These multiple years of data represent students beginning at different times. For example, when analyses are conducted on a student’s initial FAFSA, some of those initial FAFSAs were filed in 2010, whereas others were filed in 2013. To determine average changes in EFC, the author calculated the year-to-year differences in EFC, then averaged those differences.

Three groups of interest

Although this report explores the feasibility of a one-time FAFSA for all students, it particularly focuses on three often overlapping types of students who most stand to benefit from a one-time FAFSA:

- Independent students: These are students whom the federal aid system assumes are paying their own way through college. Thus, their parent or guardian’s financial information is not considered by the FAFSA. An independent student is someone who is an undergraduate older than age 24 or who is married, has dependents of their own, or who has served in the military. Students in certain dire circumstances, such as those who are homeless, orphans, or wards of the court, are also classified as independents.31

- Pell Grant recipients: These students have a low EFC, which qualifies them for this need-based grant. Although thresholds for a maximum Pell Grant-eligible EFC change each year, in the years studied, this generally referred to students with EFCs of $5,000 or less. There is an inverse relationship between EFC and Pell Grant eligibility, with $0 EFC students receiving the most grant eligibility—typically about $5,000 in each of the years studied.

- Students with a $0 EFC: These students are eligible for a maximum Pell Grant award. Although they are also represented in the Pell Grant recipients group, they need to be considered separately, because they have been determined by the federal need analysis formula to have no resources to contribute to paying for college costs. This group also represents somewhat of a catchall for students with the most need, as EFCs cannot be negative numbers.

These groups are the most likely to be affected by a one-time FAFSA, as they are the recipients of nearly all federal grant aid, as opposed to the students who fill out the form just to gain access to student loans that mostly do not depend on financial need. The groups of students noted here are also the most likely to benefit from decreased burden and stable funding. Independent students have lower completion rates compared with dependents; about one-third complete a credential within six years of enrolling, while more than half of dependents do.32 Low-income students, meanwhile, are half as likely to earn a credential as their high-income peers.33 Guaranteeing aid from year to year could go a long way in providing these students the financial stability they need to graduate.

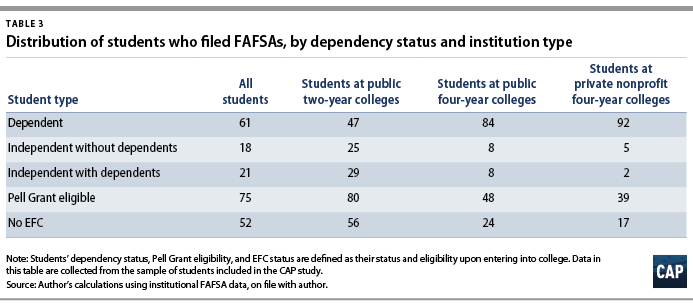

Table 3 describes the distribution of students in the study by sector. The greatest share of Pell Grant-eligible students and independent students attended community colleges, while most of the dependent students attended public four-year and private nonprofit four-year colleges.

Students’ EFCs upon starting college

If the federal government transitioned to a one-time FAFSA, a student’s aid eligibility for the entirety of their enrollment would be based on the first EFC calculated. It is therefore necessary to understand students’ EFCs when they begin college, as they form the baseline for future EFC changes.

Initial EFCs represent each student’s first EFC at a given institution. Most students in this study first filed a FAFSA with their institution between 2010 and 2013. Due to the nature of institutional data, it was not possible to observe if the student previously or subsequently filed a FAFSA at another institution.

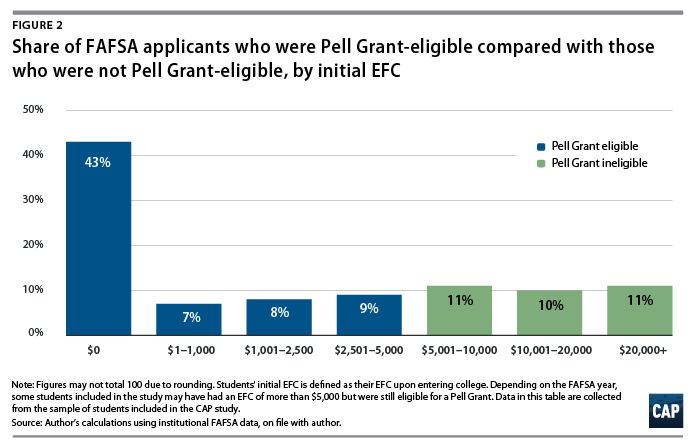

A large share of students in this study, 67 percent, had EFCs of less than $5,000 when they entered college. Figure 2 shows the distribution of students’ EFCs, with Pell students denoted as those with an EFC of $5,000 or less.34 Among Pell students, EFCs skewed very low, with 2 in 5 students having a $0 EFC when they first filed.

When the data are disaggregated by dependency status, it becomes evident that independent students are much more likely to have Pell Grant-eligible EFCs. This is especially true for independent students with their own dependents, nearly 80 percent of whom had a $0 EFC when they first filed the FAFSA.

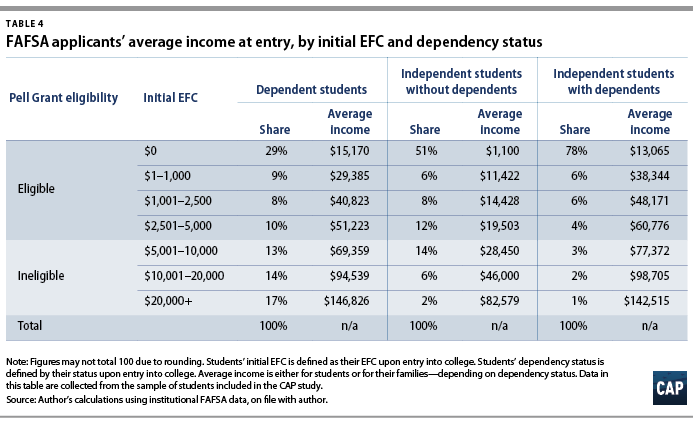

Table 4 shows the relationship between EFC and average family income in the student’s first year of enrollment. Independent students who entered college without dependents had the lowest incomes across the board, with earnings that were less than half of those of dependent students and independent students with dependents. Although they had higher average earnings, independent students with dependents were more concentrated in the $0 EFC group, with nearly 80 of students falling into that category.35

Changes in students’ EFCs

Having established students’ initial EFCs, it is now necessary to determine how much their EFC changed while enrolled. This section begins by looking at the average EFC change for the entire population of students. It then breaks down how much EFCs change for the three groups of interest: independent students, Pell Grant recipients, and $0 EFC students. These are the groups for whom a one-time FAFSA matters most, as they are most likely to be burdened by the annual FAFSA and pose the most potential federal budgetary costs for this idea.

As noted in the “Data and methodology” section, about half the students in the sample filed FAFSAs at their college for only two years. For the students with more than two years of FAFSA data, the changes in EFC reported in this section represent the average difference across all years beyond the first year.

Overall, the results show that EFCs are stable for about half of all students but that the students who receive the most federal grant aid have extremely stable EFCs, making a one-time FAFSA a reasonable reform.

Average change in EFC

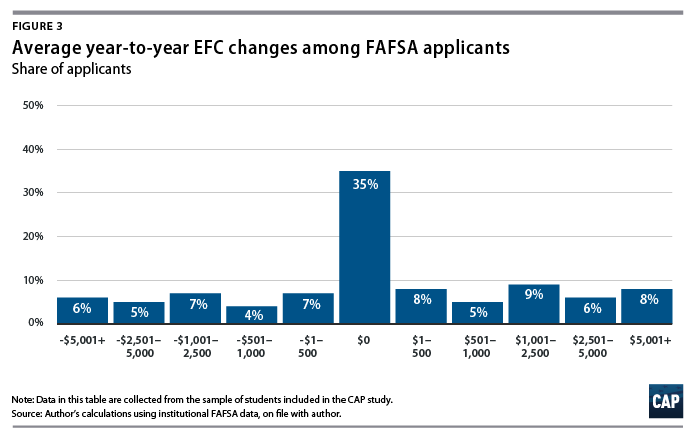

Overall, one-third of all students in the study had no change to their EFC while enrolled. (see Figure 3) When factoring in students with a change of $500 or less, half of students had stable EFCs. A little more than one-third saw a change of $500 to $5,000, and 14 percent experienced changes in excess of $5,000.

Students experiencing changes in their EFCs

Understanding the distribution of EFC changes is helpful, but it is necessary to understand if some types of students have more stable EFCs than others. For example, if Pell Grant-eligible students are more likely to have stable EFCs, then a one-time FAFSA would be feasible, as their first-year award would already be indicative of their future eligibility. Conversely, if Pell students have volatile EFCs, then a one-time FAFSA would not be feasible, as federal aid eligibility would be less predictable based on a student’s first FAFSA.

Low-income students have very stable EFCs

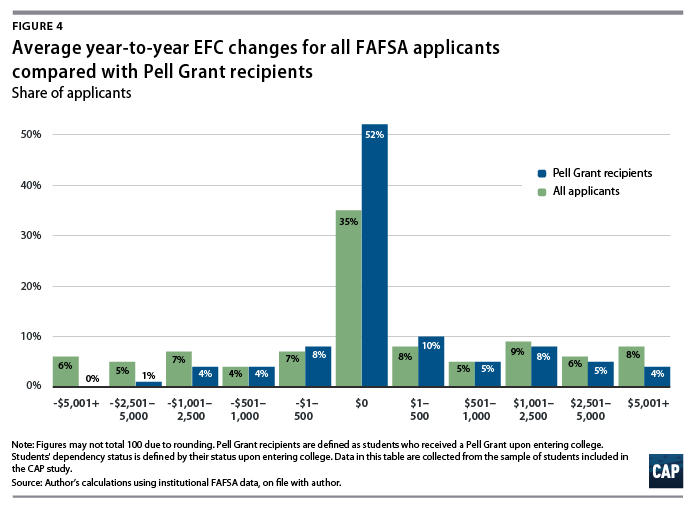

A closer look at Pell Grant-eligible students shows higher levels of EFC stability than those of the overall population. A slight majority of Pell Grant-eligible students had no change in EFC during their enrollment, and an additional 18 percent saw a change of $500 or less in either direction. Just 4 percent of Pell students had an EFC change of more than $5,000, a figure that would render them ineligible for a Pell Grant regardless of their starting EFC.

To gain additional insight into how much Pell students’ EFCs change during enrollment, Figure 5 shows the average change in EFC based on a student’s initial EFC. It shows that almost 90 percent of students who began with a $0 EFC experienced little to no appreciable change in their ability to pay, as determined by the federal government. The stability for students with a $0 initial EFC is likely due to the fact that EFCs cannot be less than zero; thus, very low-income students all cluster around that single number.

By contrast, almost all other students experienced a year-to-year change, although that change was less than $500 in either direction for many Pell Grant-eligible students. Families with initial EFCs out of the Pell Grant-eligible range were more likely to have larger EFC changes. The result is that as initial EFCs increases, students are more likely to see a change in their EFC from a subsequent FAFSA, and those changes were more likely to be larger in magnitude the greater the student’s initial EFC. For example, more than half of students who had an initial EFC of more than $20,000 experienced an EFC change of more than $5,000 while they were enrolled. This is logical: The more income and assets a family has initially, the more variables there are to affect the initial EFC.

The findings from Figure 5 have positive implications for a one-time FAFSA. There is a high degree of EFC stability for students who are Pell Grant-eligible. The higher volatility of EFCs for higher-income families, meanwhile, has minimal implications for the federal cost of a one-time FAFSA. These families already have EFCs well above the amount that would qualify them for any federal grant aid that is awarded based upon financial need. A one-time FAFSA for these families might affect receipt of subsidized loans only.

The implications of Figure 5 for state or institutional aid are less clear. Some colleges and states may award need-aware grant aid—which considers both need and merit—farther up the income spectrum than the federal government and therefore care about capturing these changes. However, data show that few students fall in these categories. In the 2015-16 school year, slightly more than 6 percent of students with an EFC of $5,000 or more received need-based state aid, and almost 12 percent of these individuals received need-based institutional aid.36

Independent students had more stable EFCs than dependents

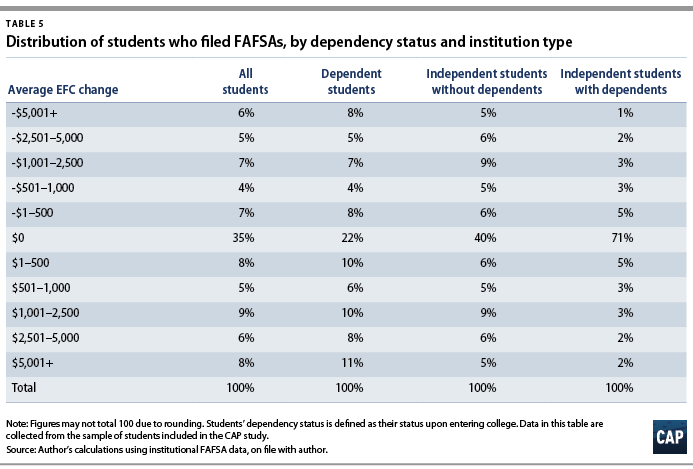

Independent students have stable EFCs compared with their dependent peers. (see Table 5) For those without dependents, 40 percent had no change in their EFC, and an additional 12 percent had a change of $500 or less in either direction. Independent students with dependents overwhelmingly experienced the same EFC from year to year, with 4 in 5 experiencing an EFC change of $500 or less. Just 3 percent had a change of more than $5,000.

Dependent students had more EFC variation. Less than one-quarter had no change in their EFC, with another 18 percent having a change of $500 or less. Almost 20 percent experienced a change of more than $5,000, though—more than double the share of independent students without dependents and more than six times the share of independents with dependents.

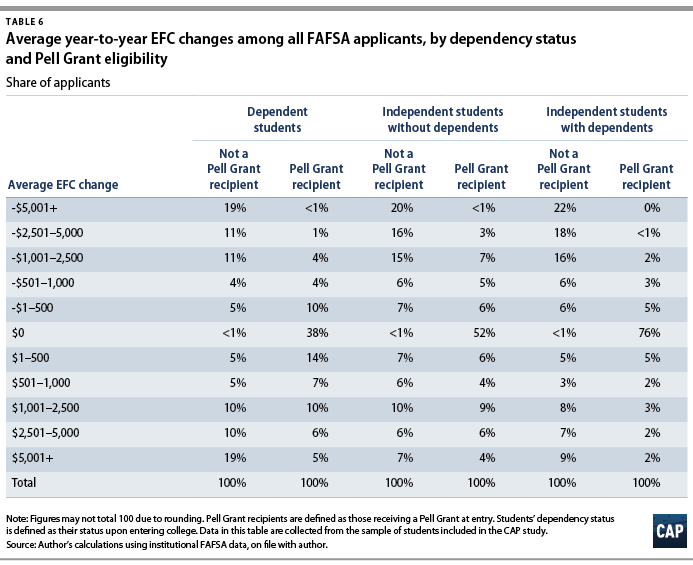

Of course, these populations overlap with Pell Grant recipients, and the previous section noted the EFC stability of Pell Grant recipients, particularly those with a $0 EFC. Table 6 shows how EFCs varied for students based on their dependency status and Pell Grant eligibility when they first enrolled in college.

The results show clearly that across all dependency statuses, non-Pell students were much more likely to experience a change in their EFC than Pell students. Sixty-two percent of dependent students, 64 percent of independents without dependents, and 86 percent of independents with dependents experienced a change of less than $500 in their EFC.

That said, there are many Pell students whose EFCs do change a more significant amount. In each dependency category, a larger share of Pell students’ EFCs increase rather than decrease, meaning that a one-time FAFSA could over-award grant aid to these students as they progress through enrollment.

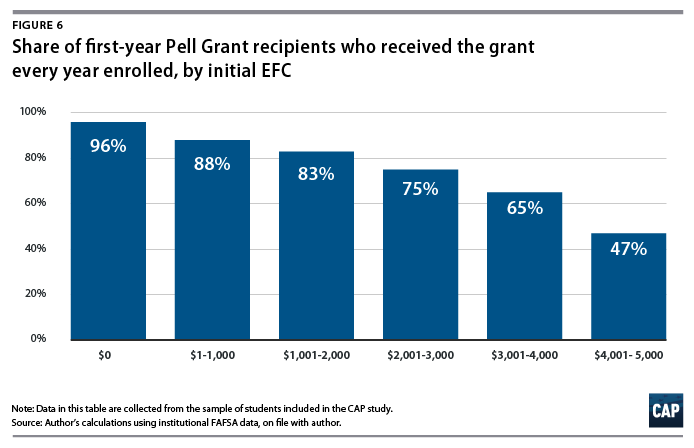

In spite of these EFC increases, Pell students overwhelmingly receive the grant each year they are enrolled. Figure 6 provides a more detailed breakdown of initial EFCs of Pell Grant-eligible students and describes the share of those students who received a Pell Grant every year they were enrolled. The data show that at the lower end of the EFC spectrum, upwards of three-quarters of students received Pell from year to year.

As initial EFCs increased, students are more likely to lose their Pell Grant at some point, with more than half of students with an initial EFC between $4,000 and $5,000 losing the grant. However, these students are also receiving the smallest grant amounts. In the 2018-19 school year, the maximum award for that EFC level is $2,045, and the minimum is slightly more than $600, depending on the student’s enrollment intensity.37 Under a one-time FAFSA, these students may receive Pell even if they would have lost it in the past. However, with the grant amounts being, at a maximum, a third of the size of the largest possible grant amount, a one-time FAFSA would represent some additional cost to the federal government—a worthwhile trade-off to reduce application burdens and guarantee stable funding for the lowest-income students.

Drivers of change in students’ EFCs

The data described above show that a one-time FAFSA would be most feasible for low-income and independent students, because they tend to have very stable EFCs. This section explores what drives changes in the EFCs of students who have year-to-year variation. A better understanding of these changes can help identify how a one-time FAFSA policy can be implemented to appropriately account for factors that cause this variation.

The need analysis formulas that determine the EFC take into account several pieces of data, including demographic information, active and passive income, assets, and savings. However, research has found that four factors largely determine a student’s EFC: adjusted gross income, dependency status, the number of individuals in the immediate family, and the number of family members enrolled in college.38

It is self-evident how income affects the EFC. Changes in the number in the immediate family or in college—both referred to in this report as changes in family circumstances—affect the EFC, because the FAFSA operates under the assumption that household resources are split among family members. Thus, adding or subtracting family members affects how much is left to pay for college. Similarly, if a family has two children in college at once, its EFC must account for the fact that the family is paying for the educational expenses of more than one child.

The institutional data used in this report allow further investigation into how frequently these factors change while a student is enrolled and how prevalent they are among students who experience a change in their EFC.

Students experiencing changes in family circumstances

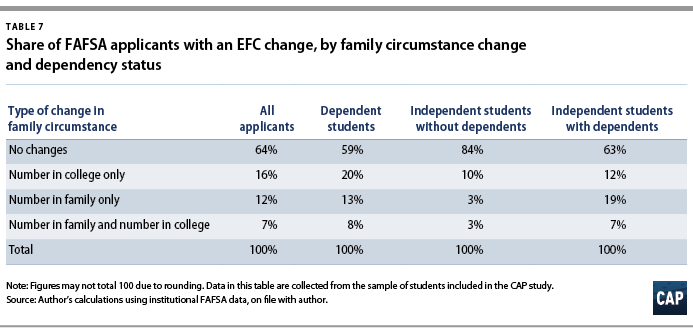

Most students who experienced a change in their EFC—61 percent—did not have a change in their family circumstances, such as a change in dependency status, the number in family, or the number in college.

Of the 39 percent of students who did experience a change in their family circumstances, 71 percent were dependents. This is somewhat logical, as dependents’ EFCs account for parents’ resources being spread among multiple children, and those siblings can cycle in and out of college. On the other hand, independent students are only liable to have a change in their family circumstances if they get married or gain dependents.

The data in Table 7 provide more detail into how much changes in family circumstance vary by dependency status for those with changes in EFC. Somewhat predictably, independent students without dependents were the least likely to experience a change in their family circumstances while enrolled. Although these students could get married or have children, they are unlikely to change dependency status—it is very rare to go from being independent to dependent—and they are much less likely to have family members who also enroll in college.

Independent students with dependents were also less likely to experience a change in family circumstances, but those who did were most likely to see a change in the number in family. This is unique from other groups and could represent gaining another dependent or a change in marital status.

For dependent students, on the other hand, a change in circumstances was most likely to be a change in the number of individuals in college—for example, a sibling or parent enrolling in or leaving college.

Students experiencing changes in income

Of the 61 percent of students who had a change in their EFC but no change in family circumstance, the variation is most likely driven by a change in income.

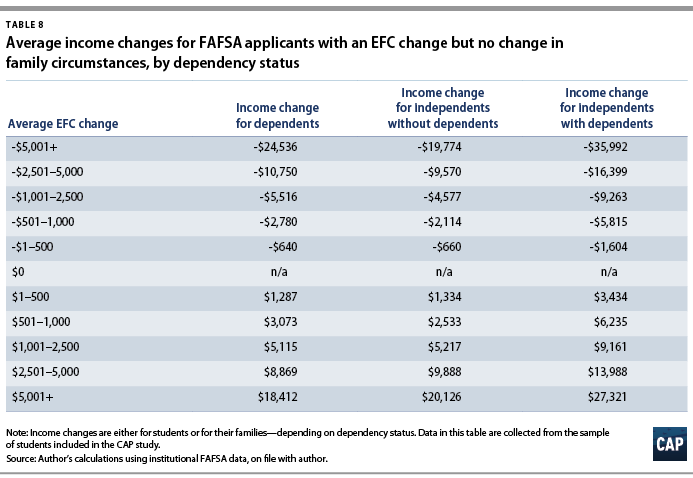

Table 8 shows the extent to which students have a change in income when their EFC changes but their family circumstances do not. Predictably, incomes increase or decrease with EFCs, and larger changes in EFC tend to reflect greater shifts in income.

Even with the implementation of a one-time FAFSA, it is clear that a student should refile if they experience a change in family circumstances. But how much should a family’s income have to change in order for them to be required to file a new FAFSA? It makes sense to answer this question using the data of Pell Grant recipients, as the federal government would be requiring students to refile if it feels the student’s income change pushed them out of Pell Grant eligibility.

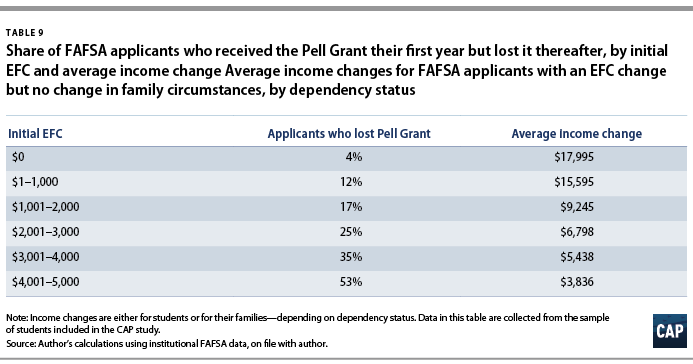

The data in Figure 6 illustrate that more than 75 percent of all students who began college with an EFC of $3,000 or less maintained their Pell Grant each year. Table 9 flips those data, examining the average income change for students who lost their Pell Grant and had no family circumstance changes. The data give an idea of what income change thresholds could be proposed by those interested in having students renew a FAFSA due to changes in income.

On the low end of the spectrum, a $4,000 change seems rather small, particularly for a lower-income family. It would be more reasonable to draw an income change threshold somewhere between the $7,000 and $10,000 mark, with the understanding that students who are receiving a Pell Grant have low incomes. Any income increases below $7,000 are most likely needed to pay for a student’s or family’s basic needs rather than their educational costs. Families should not be nickeled-and-dimed for the so-called accuracy of the EFC.

The role of assets

Assets were not a factor for most students, let alone those with the lowest incomes. Of those who had a change in EFC but no change in family circumstances, only 17 percent of dependents, 8 percent of independents without dependents, and 6 percent of independents with dependents had assets that totaled more than $5,000. As assets are highly correlated with income, many researchers have proposed removing asset questions from the FAFSA, positing that they place unnecessary complexity into the application for students who would in all likelihood not receive need-based aid.

Policy recommendations

The analyses in this report show that a one-time FAFSA is indeed feasible. Half of all students’ EFCs vary by less than $500; for Pell Grant-eligible students, that number increases to 70 percent. Independent students and those with $0 EFCs are even less likely to experience a change in their EFC from year to year. A one-time FAFSA would be most valuable for these groups, which have the most at stake in the reapplication process.

This section describes options for policymakers to consider as they approach FAFSA simplification that targets frequency of completion, as well as reducing the number of questions on the form. It considers several ways to implement a one-time FAFSA. These include applying the one-time FAFSA to all aid applicants or to more targeted groups. Each option below considers the pros and cons of the approach, balancing the goals of simplicity for students and aid administrators, as well as the accuracy of the policy in reflecting families’ circumstances. Overall, a one-time FAFSA for all students would prove the strongest approach toward simplification, reducing burden and making aid awarding more straightforward for the federal government, colleges, and students.

What about gaming?

One of the biggest concerns with a one-time FAFSA involves applicants misrepresenting or intentionally altering income data in order to receive a lower EFC and, as a result, receive a Pell Grant while enrolled in college. However, the federal government already has protections built into the application process to prevent this. Specifically, because the government uses two-year-old income tax data, those looking to game the system must plan well in advance of their enrollment in college. The Department of Education could further protect against the system being gamed by averaging students’ financial information over several years so that a student’s long-term eligibility would not be based on one year of data.

Option 1: All students complete the FAFSA just once, upon college entry

This path provides the benefit of simplicity. Every entity that advises students on applying to college, including the federal government, college counselors, financial aid administrators, and others who counsel students would have a single message: All students seeking federal aid need only complete the FAFSA one time.

With this approach, all students would have stability in terms of the amount of federal aid they receive while enrolled. This could be especially powerful for students at colleges that have adopted tuition freeze policies. These schools commit to charging students the same amount in tuition for the duration of their enrollment, rather than increasing tuition every year.39 A tuition freeze, plus a guarantee of the same minimum amount of year-to-year federal aid, would give students significantly more stable financing, providing a clearer picture of the true cost of college.

This approach would also free up a significant amount of time in financial aid offices. Without having to process, correct, and verify thousands of reapplications, financial aid administrators could focus more of their time, attention, and resources on counseling students.

The federal government would also benefit. The Department of Education would save on the cost of administering the FAFSA, which incorporates everything from paying for technology to staffing call centers. The policy could also help with budgeting, particularly for the Pell Grant program, as grant awards would be more stable from year to year.

While this is the most straightforward option, a universal one-time FASFA could also yield challenges. The findings of this report show that half of students have rather stable EFCs while they are enrolled in college—including 70 percent of Pell Grant-eligible students—but millions of students still experience larger swings. For these students, an opt-in renewal FAFSA could be implemented to allow students to note changes in income or family circumstances to have their EFC recalculated.

Under an opt-in system, students who believe their family circumstances or incomes have changed enough to warrant an amended FAFSA could submit the form; otherwise, financial aid offices could just award students based on their old FAFSA.

Modifying the initial FAFSA and building in additional automation could help improve outreach for FAFSA renewal. For example, the FAFSA could ask additional questions about the date of expected college enrollment of family members and remind students to refile the FAFSA when that date comes. The federal government could also flag students whose incomes or family sizes have changed significantly. This would require the IRS to push data, or at least a notification of a change for a FAFSA filer, to the Department of Education, which would be difficult but not impossible.

Alternatively, existing processes could handle situations such as significant drops in family income that make students eligible for larger grant awards. Financial aid administrators already have the ability to exercise their “professional judgment” if they feel a student’s FAFSA does not reflect their current financial circumstances.40 This authority could be continued under a one-time FAFSA; it might even run more smoothly thanks to time freed up from processing fewer annual FAFSAs.

The expiration period of a FAFSA would also need to be defined. Some students, particularly those who enroll part time, take time off from school, or transfer, remain in college far longer than the traditional four years. In those cases, it would be inappropriate to determine a student’s EFC based on income data that are nearly a decade old. The federal government would need to define how frequently students must complete the FAFSA in order to gather updated data: perhaps every five years—the average time to complete a bachelor’s degree—or every time a student transfers or suspends their enrollment for more than one year. The federal government could automatically notify students who must reapply using a combination of its own data and data from other federal agencies, such as the IRS.

While a universal one-time FAFSA holds many benefits, it is important to consider how the policy could be targeted to certain groups of students should policymakers raise concerns about gaming and improper payments. The next three options explore how targeting a one-time FAFSA could improve the aid application process for certain groups of students.

Option 2: Pell Grant-eligible students file the FAFSA just once, but all other students complete the form annually

This option would allow students who are eligible for a Pell Grant in their first year to maintain that EFC for several years of their enrollment, with non-Pell students having to refile the form each year. This would help guarantee stability for students who qualify in their first year and remove the obstacle of completing the FAFSA in order to receive the grant. This approach would go a long way in helping lower-income students budget for college costs.

This fix would also lessen the burden of FAFSA processing on financial aid offices. In particular, it could help prevent excessive time spent verifying income data for the Department of Education, a process that is conducted for about half of Pell Grant recipients every year.41 With about 1 in 5 students failing to complete verification, removing this barrier for Pell students may be as important an outcome as eliminating reapplication.

Of course, as a one-time FAFSA becomes more targeted, communication about exactly who must reapply becomes a challenge. Because the financial aid system is so complex, many students do not know whether or not they received a Pell Grant. Though the Department of Education and colleges could reach out to students to inform them of who needs to reapply and who does not, the effort of differentiating communication and clarifying requirements for students could take up some of the time savings of a one-time FAFSA.

Policymakers would also have to determine if other situations related to Pell Grant eligibility exempt students from needing to refile the FAFSA. For instance, would a student who qualified for a Pell Grant upon refiling the FAFSA need to fill it out again the following year? While exempting these students would provide more stability for them, it would make the program more expensive, as the number of Pell Grant-eligible students would only increase over time for every cohort of students. The data in Table 6 also show that students who are initially Pell Grant-eligible do experience increases in their EFCs. Thus, it may be necessary for the policy to flag some Pell students for renewal due to changes in circumstances. Ideally, this would be based on changes to income or family circumstances that are flagged from the initial FAFSA or the IRS, rather than a random process similar to the current verification system.

Finally, institutions and states would have to decide how to move forward with different information for different populations. More institutions, particularly those that award a significant amount of their own need-based grants, may begin to require annual institutional aid applications from Pell Grant-eligible students. States that provide significant need-based grant aid may also respond with stand-alone applications. While it is possible that institutions and states would follow the lead of the federal government and opt to keep aid stable for low-income students, thus creating a powerful wave of consistency in year-to-year aid, some students would likely face more complicated situations. Thus, any one-time FAFSA policy would have to limit the extent to which schools and states could burden students—particularly Pell students—with requests for annual information.

Option 3: $0 EFC students complete the FAFSA once, but all others file it annually

This option would provide similar benefits and costs as Option 2, but only students who first enrolled with a $0 EFC—meaning they are eligible for the maximum Pell Grant—would complete the FAFSA once. These students make up about 60 percent of all Pell Grant recipients and are those with the most need.

The data in this report also show that these students have the most year-to-year stability in their EFCs. Eighty-one percent of students who began with a $0 EFC sustained it through their enrollment. Applying a one-time FAFSA policy to only students who have a $0 EFC would remove an unnecessary barrier and guarantee aid stability from year to year.

However, tying a one-time FAFSA to a specific EFC also has drawbacks, as it creates different experiences for students who may have very similar circumstances. For example, in the data in this report, the lowest nonzero EFC is $5. Does that student really have very different circumstances from one with a $0 EFC? To prevent this from happening, the Department of Education could award the same amount of aid to students with EFCs under a certain threshold, such as $250 or $500, as it does to students with $0 EFCs.

Finally, this option would present an even greater communication barrier than applying the policy to all Pell Grant recipients: When it comes time to reapply for aid, students would need to know their EFC, not just if they received a Pell Grant.

Option 4: Independent students file the FAFSA once, but dependent students file it annually

There are several benefits to reducing burden and increasing aid stability for independent students. They make up 45 percent of aided undergraduates42 and have low median incomes compared with the family incomes of their dependent peers—$27,700 versus $66,400.43 They are also more likely to be working and enrolled part time, and they have disproportionately low rates of completion when compared with traditionally aged college students.44 Thus, removing any barriers to completion for this population would be a step in the right direction.

The data in this report also show that independent students have rather stable EFCs. This is particularly true for independent students with dependents of their own, whose EFCs tend not to vary much even when they have changes in family circumstances or income. The stability of these students’ EFCs is largely due to the fact that most students had $0 EFCs when they first enrolled, and that population tends to experience little change in EFC over time.

This option has the benefit of being a bit easier to communicate to students, since there are clearer delineations for independent students than there are for Pell Grant recipients. Still, financial aid offices and the Department of Education would be required to do more complex messaging around this policy than they would for a one-time FAFSA that applies to all students.

The major drawback to this policy is that independent students may be more likely to have a significant change in their incomes post-enrollment—such as reducing their working hours—which would make them eligible to receive larger amounts of aid. Although these data show that many independent students enter college with low incomes to begin with, financial aid administrators would have to communicate to students who stop or reduce their paid workloads that they should refile the FAFSA to determine if they are eligible for additional aid.

A stop-gap solution

A one-time FAFSA could only be implemented with a change to the Higher Education Act, a prospect that could take years.45 But the Department of Education could implement a stop-gap measure to simplify FAFSA reapplication and smooth the path toward a one-time FAFSA.

When students reapply for the FAFSA now, much of their demographic information is imported from their previous application, which makes completing the form simpler and faster. But perhaps completing a new, full form is unnecessary. Instead, students refiling the FAFSA could complete a brief questionnaire that only checks on changes that would affect their EFCs by a significant margin.

This form could feasibly be less than 10 questions, and most students would likely not need to input any tax information, especially if the form is connected to the IRS DRT and students provide multiyear consent to access those tax data. Students could answer straightforward questions about changes to the number in family, number in college, or the student’s marital status or number of dependents.

This policy would be simple to communicate, because there is no process change from the status quo. It would also simplify the process for low-income students while capturing necessary information for those whose EFCs are more likely to change.

Conclusion and next steps

Moving to a one-time FAFSA would represent a big step forward for the financial aid system. It would reduce burden and costs for the federal government, institutions, and students. Just as importantly, it could make the amount families pay for college more predictable over time. Of course, such a move would represent a major shake-up of the financial aid system, which would require adjustments from all parties involved as they adopt a new status quo. That said, proposals such as a one-time FAFSA are important to consider at this time, when they can be given due consideration in advance of the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, which the House of Representatives has considered within the last year.46

Although a one-time FAFSA may seem fraught with challenges, implementing the policy for the entire undergraduate population is feasible for the federal government and would improve the lives of students. This approach would allow for clear communication about who needs to complete and file a form and would remove a significant amount of burden placed on low-income and independent students who have stable EFCs and are most likely to receive federal grant aid.

Ultimately, a one-time FAFSA highlights how much the federal government relies on overly exacting students’ EFCs and the associated need analysis process in order to award need-based aid. Combining a one-time FAFSA with other simplification policies, such as removing infrequently answered questions from the form, would give students a new, more straightforward system—resulting in real benefits in terms of college access and affordability.

About the author

Colleen Campbell is an associate director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress. She was formerly a senior policy analyst at the Association of Community College Trustees and a research analyst at the Institute for Higher Education Policy. Prior to working in higher education policy, Campbell served as the assistant director of financial aid at the Juilliard School. Her work focuses on providing accessible, affordable postsecondary financing for underrepresented communities and adult learners. Campbell holds a master’s degree in public policy and Master of Arts in higher education from the University of Michigan.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Association of Community College Trustees and the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators for their collaboration in gathering data for this report. The author also appreciates the efforts of the colleges that generously provided data for this report. Without their work, none of this would be able to happen.

Appendix: Additional information on data collection and methodology

The data in this report were obtained directly from 27 colleges: 11 community colleges, nine public four-year colleges, and seven private nonprofit four-year colleges. These colleges are located across the country and vary in size. In the data used in this study, the largest college reported at least two years of FAFSA data for almost 32,000 students, whereas the smallest reported data for slightly less than 100.

Colleges reported starting cohort data for three award years—2010-11, 2011-12, and 2012-13—and reported FAFSA data for each subsequent FAFSA filed. Because the author received data directly from colleges, it was not possible to know if the student had completed a FAFSA previously. Therefore, when the terms “initial EFC” or “first-year EFC” are used, they refer to the student’s first EFC at that specific college, not necessarily a student’s first EFC overall.

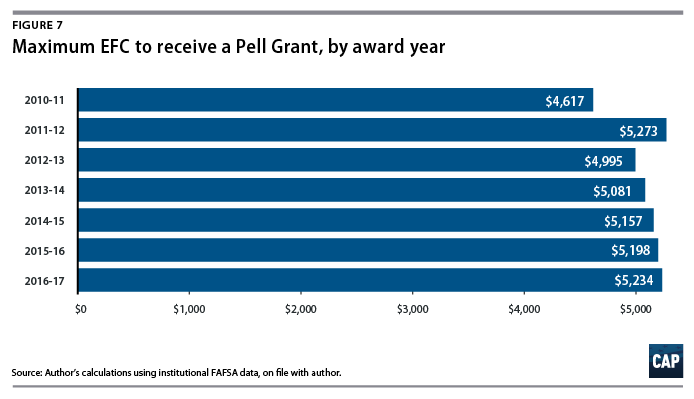

Figure 7 identifies the maximum Pell Grant-eligible EFC for each award year with at least one FAFSA included in this report. These EFCs, however, are based on full-time enrollment; the maximum Pell Grant-eligible EFC threshold for students who enroll less than full time is typically lower.47 As the colleges did not submit information on enrollment intensity, it is not possible to know if all students with a Pell Grant-eligible EFC received a Pell Grant in a given year. Therefore, the share of students who are identified as Pell Grant-eligible in this study may be slightly overestimated.

Limitations

This report provides descriptive statistics for a group of colleges. These data are not representative of the entire population of students who apply for aid each year. More research is needed to determine if the results of this study hold for all students.