The U.S. Department of Education recently released new data on student loan default rates and is touting a success story: The national default rate is 10.8 percent, down from 11.3 percent last year. But this decline doesn’t mean that students are no longer struggling to repay their loans or suffering the consequences of default.

Though data on federal loans is notably poor, over the past three years, researchers have identified certain groups of students who face particularly high risks of default on their federal student loans. The Center for American Progress and others have found that African American borrowers, students who are parents, and low-income students have higher-than-average default rates, in some cases topping 50 percent. Research has also repeatedly demonstrated that students who do not complete college are more likely to default than those who have.

These groups are relatively large and can therefore be studied in depth using the Education Department’s sample survey data, which follow students from when they entered college in 2003 through 2015. However, there are other groups of students with similarly high default rates who often go unstudied because they comprise a relatively small portion of the overall population. These students are an important part of the American postsecondary education system, yet they are too often underserved by it.

This column highlights five groups of students that debt disproportionately burdens and typical analyses neglect: veterans, first-generation college students, students without a high school diploma, students with disabilities, and underrepresented minorities.

Veterans

Veterans can receive substantial education benefits, which may help them avoid borrowing. For example, the Post-9/11 GI Bill provides veterans with funds to cover their tuition and fees while also offering monthly housing allowances and stipends for books and supplies. Veterans may also be eligible to receive additional financial aid through the Yellow Ribbon Program.

While these funds can cover a significant share of college costs, they may not be sufficient for all veterans and students may not understand how to access them. Furthermore, veterans who served prior to the eligibility period of these benefits may not have access to the same level of assistance, leaving them more reliant on loans.

The data show that veterans who do take on debt have a default rate of 46 percent, compared with 29 percent for students who did not serve in the military. Unfortunately, because veterans comprise a small portion of the overall U.S. population, the data cannot be disaggregated for other characteristics, such as types of college attended, race or ethnicity, and degree completion.

First-generation college students

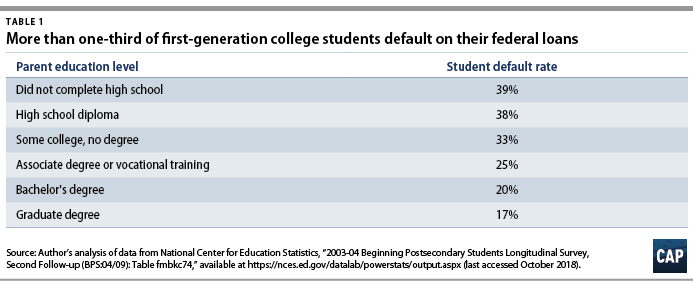

Prior research has demonstrated that first-generation college students complete their degrees at half the rate of their peers who have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree. These disparate results extend to loan repayment outcomes. Slightly more than one-third of first-generation students default on their loans, compared with 20 percent of students who have a parent with a bachelor’s degree and 17 percent of students who have a parent with a graduate degree.

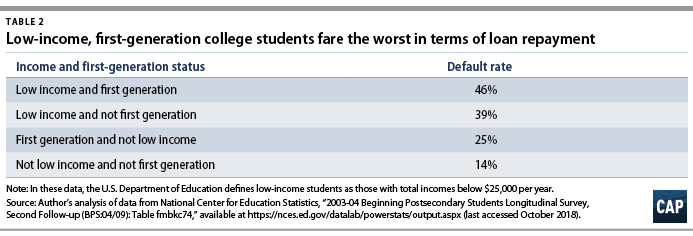

The results are even more troubling for first-generation students from low-income families, among whom nearly half default. Table 2 shows that low-income students tend to experience poor repayment outcomes, and these poor outcomes are exacerbated when low-income students are also first-generation college-goers. In fact, low-income, first-generation college students’ default rate is 20 percentage points higher than that of students who are first-generation but not low-income.

Students without a high school diploma

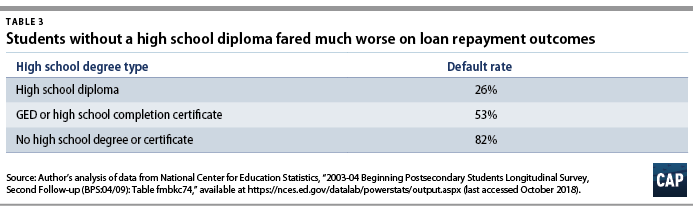

Students without a traditional high school diploma enroll in college at about half the rate of their peers with a diploma. When they do enroll, they have lower college completion rates than diploma-earners. Unfortunately, these students also struggle to repay their loans; GED diploma- earners have a default rate that is more than twice that of those with a regular high school diploma.

Students who do not earn any high school degree before enrolling in college experience the highest default rates, with 4 in 5 defaulting. Many of these students were likely enrolled in college through Ability to Benefit (ATB) programs, which allow students to pass a proficiency test in order to gain access to federal aid for postsecondary education. ATB programs have since added a requirement that students must also complete six credits of coursework, which could mean that the default rates observed in these data are not as high as they were in the past. However, it is important to understand the loan repayment outcomes among these students, as ATB is an important path to a college education for adults interested in improving their career prospects.

Students with disabilities

Students with disabilities face significant obstacles in the American education system. They are less likely to complete high school, enroll in college, and complete a credential when they do enroll. These results are due in part to the presence of various obstacles that inhibit disabled students’ ability to learn—such as barriers to accessing facilities, receiving accommodations, and interacting with faculty.

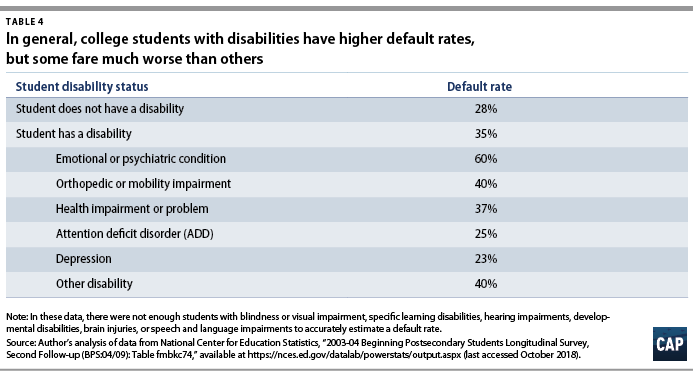

When it comes to loan repayment, students with disabilities have a default rate that is 6 percentage points higher than that of students without disabilities. Depending on the students’ disability, however, there is significant variation in default rates within this group. For example, students with mental health conditions fare the worst, with more than 60 percent defaulting within 12 years of entering repayment. Those with mobility, visual, and other impairments also face higher default rates than students without disabilities.

Even if they finish a credential, students with disabilities may encounter repayment difficulties due to lower wages and high unemployment rates. On average, disabled people who hold bachelor’s degrees earn $12,700 less a year than other bachelor’s degree-holders. This gap widens to $20,800 when comparing individuals with graduate degrees. People with disabilities also struggle to find a job; the unemployment rate for individuals with disabilities was 9.2 percent in 2017—more than twice the rate of those without disabilities.

Underrepresented minorities

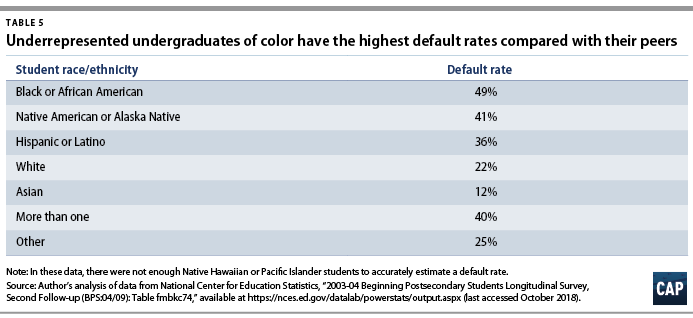

Students from underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups have higher overall default rates than white and Asian students. For example, recent research has demonstrated that African American borrowers face exceedingly poor repayment outcomes, even if they earn bachelor’s degrees.

Students who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native particularly struggle with loan repayment, with 2 in 5 defaulting on their loans. These students overwhelmingly come from low-income communities: 40 percent of the poorest counties in the United States are located on reservations, and Native Americans have the lowest share of adults with bachelor’s degrees among all racial and ethnic groups.

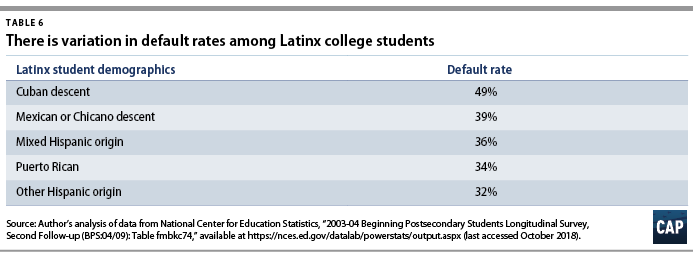

Hispanic or Latino students also face a higher default rate than the national average—36 percent compared with 29 percent, respectively. Within the Latino community, students of Cuban descent have the highest default rates. These data suggest that there could be variation in loan repayment outcomes within ethnicities of other races, such as students of Asian descent. Unfortunately, the Department of Education’s survey does not collect this information.

Conclusion: Promoting equity in postsecondary education

Although loans can provide financing for students who would otherwise not be able to afford college, these findings cast doubt on how well the federal student loan program promotes equity. Federal programs exist to provide additional funding and support to students who belong to the groups identified in this analysis. Yet, it is clear that student loans are still preventing these communities from fully realizing the opportunities that postsecondary education provides.

While the American higher education system is not solely to blame for this failure to consistently and effectively serve these groups of students, there are steps that can be taken to improve the situation. First, the Department of Education must make additional information available so that researchers and policymakers can better understand the outcomes of vulnerable students and appropriately target reform efforts.

Policymakers should also follow the recommendations outlined in CAP’s “Beyond Tuition” report, thus ensuring that institutions are held accountable for closing equity gaps; states provide equitable funding for postsecondary institutions; and students can access programs that reduce the burden of high monthly student loan payments.

Federal student loan default can have devastating effects on students. It can prevent them from receiving federal student aid, reduce their credit scores by up to 100 points, and lead to the denial of a professional license. Borrowers may also have their paychecks, tax refunds, and Social Security benefits docked to pay down their debt after they default—a consequence that can hit low-income and disabled borrowers the hardest. Although the data suggest that many students are able to exit default, the paths out are confusing and costly. The findings in this column emphasize that it is time for policymakers to provide relief to student loan borrowers and ensure that students have access to straightforward, fair options to pay down their debt.

Colleen Campbell is an associate director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.