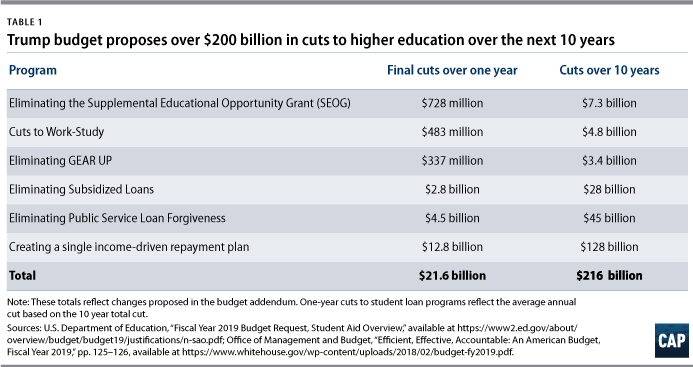

In December, Congress passed one of President Donald Trump’s key priorities: tax cuts. These cuts primarily benefit the wealthy to the tune of $1.5 trillion in deficit spending over 10 years. To pay for it, the budget released this week proposes cutting over $200 billion in student aid funding over the next decade by eliminating some types of federal student loans; changing the loan repayment safety net; and ending forgiveness for borrowers who work in public service. And it would cut over $1.4 billion in annual grant aid and student support to low-income students.

Last week, a congressional budget deal raised caps in spending, amounting to an additional $2 billion for higher education in both 2018 and 2019. To account for new spending levels, Trump’s original budget proposal came with an addendum that walked back some of the cuts in light of the new funds available.

Even with those tweaks, this raid on higher education programs is big enough to pay twice over for a decade of Trump’s estate tax cut, a giveaway for the children of multimillionaires.

Cuts to student aid would push many students into more debt. It would do nothing to help the thousands of students experiencing food insecurity or struggling to balance full-time work and child care while seeking a college degree. Some deserving Americans may give up on the idea of attending college at all.

To be fair, the budget does contain a handful of small, good ideas. This includes automatically enrolling delinquent borrowers into a program that would make their loans more manageable and requiring that colleges face some accountability if they cannot produce graduates who are able to get decent jobs and repay their loans. However, the budget does nothing to meaningfully address affordability or equity for students from all backgrounds.

Here’s a look at what students have to lose if the budget were enacted:

Significant cuts for student loan borrowers

The most significant cuts in Trump’s budget come from a major overhaul of the federal student loan program. Just like the administration’s 2018 budget, the proposal seeks to eliminate both subsidized loans as well as Public Service Loan Forgiveness and redesigns income-driven repayment, the program that allows borrowers to cap the size of their loan payments if they have a limited income. On the positive side, it also proposes some long overdue changes to help borrowers stay out of default and to hold institutions accountable if their students cannot repay their loans.

Eliminates Direct Subsidized Loans

The Trump budget deals a major blow to student loan borrowers by proposing to eliminate Subsidized Stafford Loans, which allow undergraduates with financial need to avoid interest accruing on their loans while they are in school or if they experience periods of unemployment or financial hardship. The program is mostly used by students from low- and middle-income families: More than half of subsidized loan recipients’ families make less than $60,000 per year. About 70 percent of students who receive subsidized loans also qualify for a Pell Grant, which targets low-income students.

The cut would shift approximately $2.8 billion in costs each year from the government onto nearly 6 million students. For example, if a student borrowed their Subsidized Stafford Loan maximum, $23,000, they would be on the hook for more than $5,000 in interest by the time they left school. Under a standard 10-year repayment plan, this would increase students’ monthly payments by almost 20 percent.

Ends Public Service Loan Forgiveness

The Trump budget continues the trend of congressional leaders and this administration calling for the end of the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). The program allows nonprofit workers and government employees—including teachers, public defenders, police officers, and firefighters—to receive loan forgiveness after 10 years of payments. Borrowers only qualify for PSLF if they also use an income-driven repayment plan at some point.

Ending PSLF would put public servants on the hook for $45 billion in debt payments over 10 years.

Reforms income-driven repayment

As with its 2018 budget proposal, the Trump administration would like new borrowers to have only one income-driven repayment plan option. Under this plan, all borrowers would make loan payments equal to 12.5 percent of their discretionary income each month. For undergraduate borrowers, they would do so until they paid off their loan balance, or for 15 years, at which point any remaining balance is forgiven. By contrast, students with any graduate loans would be expected to pay for 30 years before reaching forgiveness.

This differs from the two most recent income-driven repayment options in that the amount of discretionary income devoted to a payment is higher (12.5 percent as opposed to 10 percent on the other plans). Undergraduate borrowers would have a lower maximum time they could spend in repayment (15 years versus 20 years). But graduate students on the current plans do not receive forgiveness for 20 or 25 years, so the 30-year window in the budget would require more years in repayment.

For many undergraduate borrowers, the combination of paying more per month and shortening the forgiveness term means those borrowers may pay less over the life of their loan compared to current borrowers on income-driven repayment. For all but a few graduate student borrowers, however, increasing the amount of income going to loan payments and extending the number of years until forgiveness will result in these borrowers paying substantially more.

Payment terms aside, there is some decidedly good news in the administration’s plans for income-driven repayment. First, the administration proposed allowing borrowers to let the Department of Education pull their income data from the IRS for several years so that borrowers do not need to verify their income each year, a bit of bureaucracy that trips up many borrowers. The Center for American Progress proposed a plan along these lines in August 2016.

Second, the proposal seeks to automatically enroll severely delinquent borrowers in an income-driven repayment plan. This welcome change would ensure that those borrowers are on a plan that keeps their debts affordable, including the ability to pay nothing if their income is low enough.

Supports repayment-based accountability

The administration also proposes making institutions accountable for their students’ loan repayment outcomes. Though the plan is short on details, the budget says “a better system would require postsecondary institutions accepting taxpayer funds to share a portion of the financial risk associated with student loans.” The budget’s suggestion that schools should be accountable “in consideration of the actual loan repayment rate” seems to signal an interest in new metrics for loan repayment that capture other bad outcomes beyond default, which is the sole loan outcome on which colleges are currently judged.

There is potential for a loan repayment measure to improve on our current, very limited system of accountability for colleges. But Congress must get the details right. CAP commissioned a series of risk-sharing proposals that lay out the intricacies of such a policy.

Freezes the maximum Pell Grant

The Trump budget allows the Pell Grant to erode in value against inflation while expanding eligibility to untested short-term programs.

The budget proposes no increase to the maximum Pell Grant award for the next decade. This all but guarantees that the percentage of college expenses covered by the award will continue to decline from its current level. The Pell Grant, which is the federal government’s bedrock program to make college affordable for low-income students, covered about 80 percent of the cost of attending a four-year college in 1975. Today, it covers just 30 percent.

Instead of holding the line on the value of the Pell Grant, the budget proposes allowing students to use these funds to attend short-term training programs. While some short-term programs may provide sufficient value to merit receiving a Pell Grant, there’s no evidence to justify a widespread expansion. The call for expanding the Pell Grant program at this time is particularly odd because the Department of Education has yet to publish an evaluation of an experiment that tested a version of this idea.

The original version of the budget also proposed a cut to the program’s accumulated surplus of $1.6 billion. This comes after Congress cut $1.3 billion from the surplus in the 2017 appropriations process. The budget projects that a further surplus reduction could leave the Pell Grant program with a shortfall as early as 2022 or 2023, which would likely lead Congress to reduce federal student aid benefits. However, a budget addendum that reflects a recent agreement to increase spending caps suggests using those additional funds to undo the surplus cut.

Estimates of the impact of a Pell Grant freeze on college affordability by state are available here.

Eliminates other grant aid and guts the Federal Work-Study program

While the budget proposes to weaken the Pell Grant program, it eliminates other grant aid for low-income students entirely. The Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (SEOG), which provides $732 million in grant aid to 1.6 million students, is slated for elimination. While this program is less well-targeted to the neediest students than the Pell Grant, approximately 80 percent of SEOG aid goes either to students whose families earn less than $30,000 or to independent students, who are more likely to be low-income. Another 17 percent of aid goes to families making between $30,000 and $60,000 a year.

The budget also proposes slashing the Federal Work-Study program to a fraction of its current size, while “reforming” it to support “workforce and career training opportunities.” The administration originally sought to cut $783 million dollars, or 80 percent, of the total Work-Study budget. The budget addendum would restore $300 million in spending, leaving a total cut of $483 million.

Work-Study subsidizes employment for students, including jobs on and off campus. The administration justifies the massive cut by noting that most of the aid goes toward higher income undergraduate and graduate students. It also proposes reforming the institutional allocation formula to prioritize institutions based, in part, on Pell Grant recipient enrollment.

The Work-Study program is indeed less well-targeted to the students who would most benefit from it, and the allocation formula is in need of reform. But cutting 80 percent of the funding is a laughable way to fix a program that helps thousands of students with financial need and could help even more if it were genuinely redesigned. This proposal would mean that significantly fewer students would receive any aid at all.

In 2016-17, roughly 630,000 students received Work-Study awards. The original budget proposal would have left just 133,000 students with an award, a figure that rises to 330,000 with the funding restored in the addendum.

Estimates of the number of students and the amount of subsidized loans, Work-Study funds, and SEOG grant aid received in each congressional district and by state can be found here.

TRIO and GEAR UP under threat

The proposal fundamentally alters the structure of the federal TRIO programs from a competitive federal grant program to a state block grant formula program. TRIO programs provide support to low-income and first-generation students ranging from tutoring and mentoring to research opportunities. The proposed change would portion out money to states, which would then decide which programs get funding and how much. Block grant programs are particularly vulnerable to funding cuts over time, as a study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows. That is because states often divert the money to fill other purposes.

The original budget proposal sought to cut $393.5 million from the TRIO programs and reform how funds are allocated. This is a 40 percent cut in funding to the programs. The budget addendum, however, proposes no cut to TRIO programs and funds them at the level previously awarded.

The administration would also eliminate entirely Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs (GEAR UP). GEAR UP provided $337 million toward college prep opportunities for low-income elementary, middle, and high school students.

Uncertainty for HBCUs and Minority Serving Institutions

Many of the institutional capacity-building programs for minority-serving institutions, which are authorized under Title III and V of the Higher Education Act, see significant changes in the Trump budget. First, the budget eliminates the $86 million Strengthening Institutions program, which provides funding to improve academic quality and institutional capacity.

The budget then forces certain types of minority-serving institutions into an awkward trade-off by guaranteeing access—meaning that more institutions would get grants, but the grants could be far smaller. The budget does that by converting competitive funds for five types of schools into a $147 million formula grant. Those schools include Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian-Serving Institutions; Predominantly Black Institutions; Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions; Native American-Serving Nontribal Institutions; and Hispanic-Serving Institutions. This fund would allocate dollars based on factors such as the number of Pell Grant recipients enrolled; the number of graduates; and the number of graduates who are attending graduate or professional school.

This change could dramatically shrink the size of awards colleges receive. For example, the $116 million program for Hispanic-Serving Institutions provides awards for just 199 of the 472 institutions in this category. Giving all Hispanic-Serving Institutions an award may spread the pool of funds so thin that the money cannot meaningfully help schools.

The budget also flat funds Tribal Colleges and Universities; Hispanic-Serving Institution stem programs; and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) at the fiscal year 2017 level.

Conclusion

It may be tempting to dismiss Trump’s budget request as inconsequential, since Congress could, and has in the past, ignored wide swaths of it. But supporters of a quality higher education system open to students from all walks of life should be aware that there is a new conservative vision coalescing around the idea of severely curtailing public support for an affordable college education.

In December, the House education committee sent to the full House of Representatives a bill to rewrite the Higher Education Act. The Promoting Real Opportunity, Success, and Prosperity through Education Reform (PROSPER) Act includes many of the same cuts originally proposed by the Trump administration and also seeks to eliminate safeguards that prevent students from being taken advantage of by unscrupulous colleges.

Given the rising cost of college, the declining value of the Pell Grant, and the crisis of defaults among far too many borrowers, the United States needs to invest more in its higher education system rather than pursue an ideological agenda that limits opportunity for millions of Americans.

Marcella Bombardieri is a senior policy analyst on the Postsecondary Education team at Center for American Progress. Colleen Campbell is the associate director on the Postsecondary Education team at the Center. Antoinette Flores is a senior policy analyst on the Postsecondary Education Policy team at the Center. Sara Garcia is a policy analyst on the Postsecondary Education team at the Center. CJ Libassi is a policy analyst on the Postsecondary Education team at the Center. Ben Miller is the senior director of the Postsecondary Education Policy team at the Center.