Last week, the U.S. Department of Education announced that it will hold a May meeting to help decide whether the problematic accrediting agency Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS) should again be allowed to grant access to federal financial aid. In late 2016, the agency lost its ability to act as a gatekeeper to federal student aid—shortly after a Center for American Progress analysis showed that, for years, it had been little more than a rubber stamp for failing colleges.

Making the announcement more troubling is the fact that a new data review shows that if ACICS makes a comeback, it will be serving schools that seem to have drawn little interest from other accreditors. This suggests two things: First, contrary to attention-grabbing reports, most of the affected schools—and the students they enroll—appear to have already moved on or at least have a clear path to being considered by another accreditor. Second, the Education Department’s announcement raises questions about whether there is value in bringing back an accreditor that only approves schools that did not find acceptance from peer agencies.

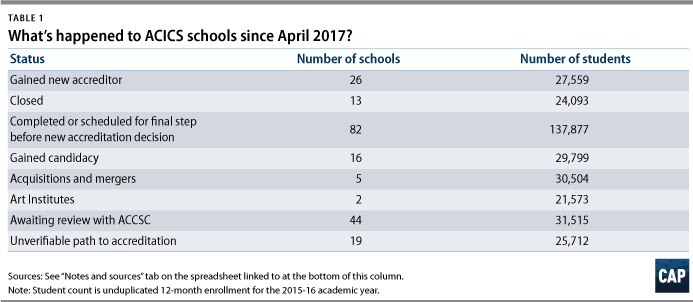

ACICS’ loss of gatekeeper recognition in 2016 kicked off a process that gave the schools it oversaw 18 months—until June 12, 2018—to find a new agency. Based on CAP analysis of public documents from accreditation agencies as well as institutional websites, it appears that the vast majority of ACICS institutions now fall into one of the following categories:

- They have already obtained new accreditation elsewhere.

- They recently reached the final review step at a new accreditor or are scheduled to reach that step before June 2018.

- They have closed or announced plans to close.

Out of the 269 institutions that had accreditation through ACICS when it lost approval, there are only 19 whose progress toward receiving accreditation was unable to be verified through public records.

This matters because efforts are ramping up to pressure Congress to extend the June 12 deadline for institutions. In early January 2018, the trade association that represents private for-profit colleges sent a letter to Congress claiming that supposedly more than 155 schools and at least 235,000 students could lose access to federal aid if legislators did not act. CAP’s analysis, however, shows that the overwhelming majority of colleges are on path to get new accreditation by the deadline. The handful of colleges that do remain appear to have either been rejected by other accreditors, or CAP was able to verify their progress toward receiving approval from another agency. In other words, additional time would simply provide a longer operating window for a set of schools that already appear unlikely to get accreditation elsewhere.

Below are estimates of the status of ACICS colleges by number of institutions and 12-month unduplicated student enrollment, which refers to the total number of students enrolled for credit at any point during a year.

State of play

According to federal data, when ACICS lost its gatekeeper role, it oversaw 269 institutions that enrolled a combined 527,000 students. This figure substantially overstates the actual situation in several ways. First, it represents the unduplicated number of students enrolled in a 12-month period. Second, the figure includes a number of institutions, such as ITT Technical Institute, that had already closed or announced plans to close. Third, the enrollment total is based upon older data. The rest of this column uses 12-month enrollment data for 2015-16, which captures more recent declines.

By April 2017, the number of institutions seeking an accreditor had fallen. Closures as well as a few schools obtaining a new accreditor and others being labeled ineligible by the Education Department resulted in there being 207 ACICS colleges—enrolling 328,632 students—seeking a new accreditor last spring. By far the single biggest change in the student count was a result of the removal of the roughly 100,000 students who were enrolled at ITT Technical Institute.

Using updated student enrollment data, this column determines what has happened to those 200 institutions since April.

1. Gained new accreditor or closed

A review of public documents listing accreditor actions and institutional websites shows that 26 institutions, which enrolled a combined 27,559 students, obtained accreditation at some point between April 2017 and January 2018.

Over that same time period, 13 institutions, enrolling a combined 24,093 students, closed. While that number seems high, about half of the schools and 22,887 of the students were from former branches of Corinthian Colleges Inc., which was shut down by its new owner. Following the collapse of Corinthian Colleges, Zenith Education Group took control of 56 of the former campuses. In November 2017, Zenith announced it was closing all but three campuses because of lagging enrollment and other problems that made it unsustainable. Taking out institutions that either gained new accreditation or closed leaves 168 institutions—enrolling 276,980 students—still seeking a new accreditor.

2. Went before an accreditor commission or are scheduled to do so

Many ACICS institutions do not yet have accreditation but are close to receiving approval elsewhere. According to public accreditor data and institutional websites, there are 82 ACICS schools, with 137,877 students, that either went before an accreditation commission or are scheduled to sometime in late 2017 or early spring of this year—prior to the June 12, 2018, deadline. These institutions have reached the final stage of the accreditation process and are waiting for the agency’s commissioners to decide if they merit approval. In a few cases, this process includes institutions that have already been before a commission and were deferred for future consideration. A favorable decision would result in schools quickly becoming eligible for federal student aid if they sought it.

To be fair, these schools are not guaranteed to be approved. However, by reaching this stage, they all receive a chance to have their cases for accreditation heard by the commission to which they applied.

3. Candidate for accreditation

There are another 16 institutions, with a combined 29,799 students, that have not been granted accreditation yet but have achieved candidacy status with an accreditor. For some institutions that earned this status at a regional accreditation agency, this should mean that they are able to receive federal financial aid.

4. Anticipated acquisitions or mergers

Another five institutions, enrolling 30,504 students, are in the process of being acquired as branches of other already-accredited institutions. The majority of campuses in this category are owned by Delta Career Education Corporation. These colleges serve 30,080 students and operate under the brands of Berks Technical Institute, McCann School of Business and Technology, and Miller-Motte Technical College. The fifth school, Tribeca Flashpoint, which enrolled 424 students, will likely be acquired by Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC)-accredited Columbia College Hollywood.

The Delta Career Education acquisition is an interesting development. According to Department of Education data, it had initially applied to the Accrediting Council for Continuing Education and Training (ACCET). However, public records show that in October 2017, ACCET rejected the applications because some programs fell below the agency’s completion and job placement benchmarks. With no path to accreditation, Miller-Motte and McCann began closing some of their campuses. However, it now appears that 19 campuses under all three brands will be purchased by Ancora Education as branches of Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC)-accredited Platt College. As branches, the campuses will have to comply with ACCSC performance benchmarks and other standards. Both McCann and Berks Technical are reporting ACCSC accreditation on their websites.

5. Remaining institutions

After removing the schools that have gone before a commission, will go before a commission, gained candidacy, or were acquired, there are 66 institutions, with just over 79,000 students, seeking accreditation. A closer look at these schools, however, reveals a few key stories worth mentioning.

The Art Institutes: 2 institutions and 21,573 students

Nearly 30 percent of student enrollment at institutions that do not yet have a clear path to accreditation is at two branches of the Art Institutes. These campuses are trying to become branches of Art Institute locations that currently have accreditation from the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools. However, the potential move is caught up in a larger decision regarding a change of ownership. The Art Institutes’ parent company, the Education Management Corporation (EDMC), is awaiting approval from Middle States on the sale of campuses to the Dream Center Foundation. It is unclear when Middle States will render a decision. On December 22, 2017, the accreditor requested more information that may affect the Art Institutes’ accreditation. Whether Middle States will address these two campuses in its broader review of the Art Institutes is unclear. Both the accreditor and the school declined requests for further comment.

ACCSC: 44 institutions and 31,515 students

The largest remaining set of institutions with unclear status are those that applied to the ACCSC. They comprise more than two-thirds of the outstanding institutions though a smaller share of the students. This is not surprising; ACCSC had the most ACICS institutions apply and received nearly double the number of applications of the next closest accreditor. Moreover, some or all of these institutions could receive accreditation before June. Unlike some other accreditors, ACCSC does not tend to publish its commission schedule months in advance. However, in 2017, from January to June, the commission met or made decisions each month. This means that in the next several months, an unknown number of institutions will still go before the commission. An agency representative confirmed via phone that dozens of colleges would be up for consideration by the commission over the next few months.

The rest: 19 institutions and 25,712 students

Details for the remaining institutions are mostly unclear. Of these, one was denied by its new accreditor, while another will likely go before a commission in late spring or early summer of this year. Notably, one of these institutions just reached a $600,000 settlement with the Department of Justice over allegations that the school received financial aid for ineligible students. The school denied any wrongdoing in the settlement.

The remaining 16 institutions include four schools that the Education Department identified as not being compliant with requirements to have an in-process application with another accreditor. According to their websites, two of the remaining institutions still seem to offer federal financial aid. Six others are listed as applying to a regional accreditation agency; however, it is not clear from the agency websites when or if the institutions will be considered. All except one of these schools had functioning websites, which suggest that they are still open.

June implications

Looking at the current status of ACICS institutions reveals a situation very different from that which the panicked January letter suggested. Only 19 institutions have an unknown path to accreditation that CAP’s analysis could not verify through public documents. For another 46 institutions, the issue boils down to the actions of two agencies: Middle States and ACCSC.

Again, these findings do not guarantee that all of the ACICS institutions will find a new accreditor. After all, the agency had been a lax gatekeeper; it would not be shocking if other accreditors looked at some schools and decided they could not meet their standards. However, what these findings do mean is that the vast majority of ACICS institutions will have an opportunity to present their cases before another accreditation agency. This matters because if these institutions get an extension on the June deadline, the biggest beneficiaries will be institutions that cannot make the cut with another accreditor, which alludes to a far different narrative than colleges not getting a fair shake because the timeline for accreditors to decide is too short. Rather than extending the timeline or reviving ACICS, policymakers should ensure proper oversight of colleges that seem to be at risk of not becoming accredited since, in the meantime, at least some are still enrolling students.

Ben Miller is the senior director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress. Antoinette Flores is a senior policy analyst for Postsecondary Education at the Center.

For a spreadsheet detailing the authors’ analysis of the status of ACICS schools, please click here.