As the #MeToo movement shines a bright light on the too-common occurrence of nonconsensual sexual advances and assaults,1 many are looking to sex education as part of a comprehensive solution. Students who are educated about what constitutes consent and a healthy relationship will be better equipped to handle themselves appropriately as young adults and employees. Lauren Atkins, a high school student from Norman, Oklahoma, discussed her sexual assault in a Babe.net article in November 2017 and then helped state lawmakers write legislation that she believes would have prevented it.2 Atkins articulated what she considers to be the promise of better sex education in an interview with Rolling Stone: “I really don’t think he did this to be a terrible human being … He didn’t know that this wasn’t allowed.”3

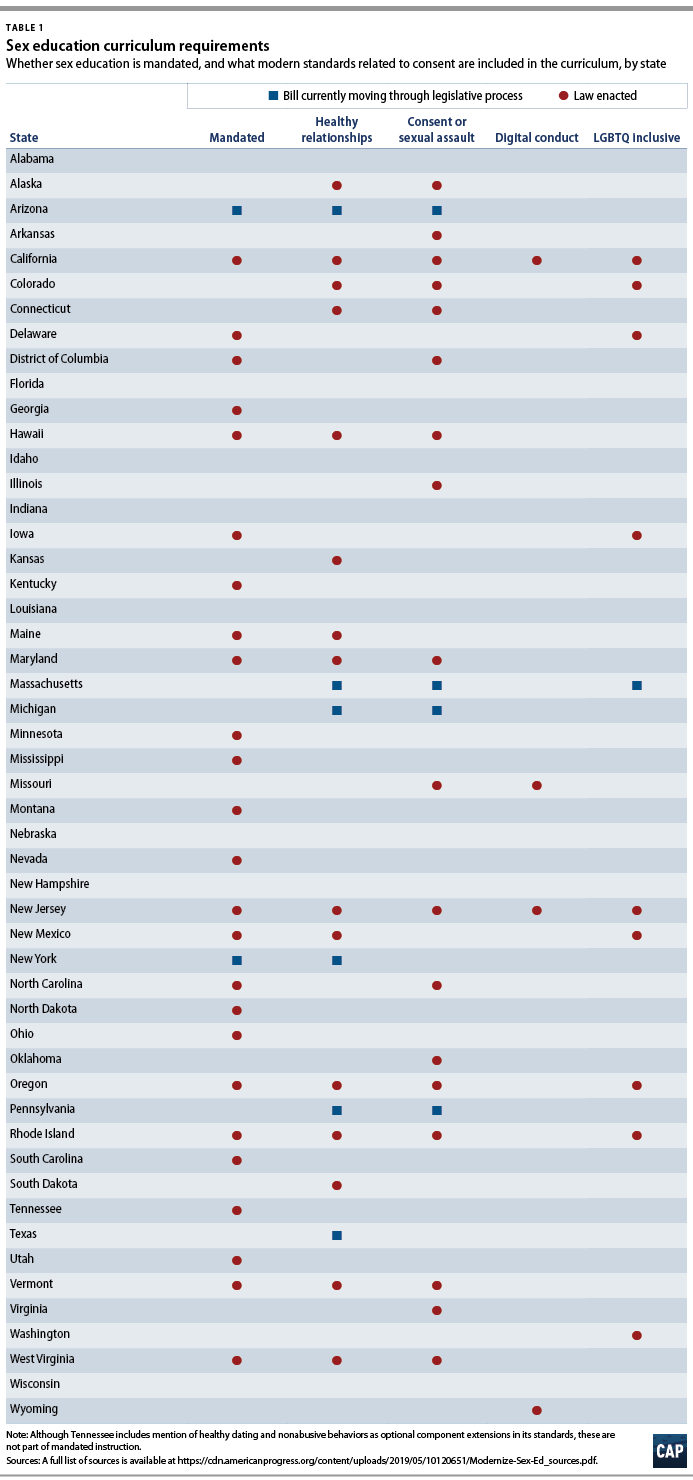

Far too often, young people don’t receive honest and clear information about how to ask for and receive consent and how to promote healthy intimate relationships. Last May, the Center for American Progress published an issue brief highlighting that, of the 24 states that mandate sex education, only 11 states and Washington, D.C., included references to healthy relationships, consent, or sexual assault in their sex education standards.4

Since then, momentum has grown to modernize sex education standards. Although CAP’s previous brief explored only the 24 states with mandated sex education, important progress has occurred in additional states, so this brief considers all of the United States. Last year, for example, six states—Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island—added language about consent or healthy relationships to their standards. Other states are taking additional steps to modernize their standards by making instruction LGBTQ-inclusive or adding information about the consequences of sharing explicit images online or through text message. This issue brief first outlines the shifting landscape of sex education in the United States and then highlights how students and newly elected female lawmakers are leading the way on this issue.

An overview of state sex education standards

All told, 21 states and Washington, D.C. now include references to consent or healthy relationships in their sex education standards.5 And state policymakers are continuing to introduce legislation: In six states, legislation has been introduced to add references to consent and healthy relationships.

There are many ways to teach this information, and states vary in how detailed they are in defining standards for discussing consent and healthy relationships. In this analysis, the authors consider that states include references to consent or healthy relationships when the terms “consent” or “healthy relationships”—or related phrases such as “sexual assault” or “dating violence”—appear in their state standards for sex education instruction.

Since CAP published its previous brief on this issue, eight states have updated their sex education standards. Maryland6 and Rhode Island7 now require that discussion of consent is included in sex education standards. While Colorado,8 Illinois,9 Missouri,10 and Oklahoma11 do not mandate sex education in all of their schools, they have added language about including consent or healthy relationships in their state standards for any schools that do teach sex education. New Jersey12 and California,13 both of which previously mandated instruction on consent and healthy relationships, passed bills to mandate sex education instruction on the consequences of online distribution of sexually explicit images. The Missouri bill also adds instruction on “inappropriate text messaging” to its standards.

In seven more states, bills to modernize sex education standards are currently advancing through the legislative process:

- Massachusetts14 introduced a bill that would make sex education curricula LGBTQ-inclusive, and both Alabama15 and Arizona16 introduced bills that would remove restrictions on the discussion of LGBTQ identities and relationships—restrictions that require negative discussion of LGBTQ identities and relationships in Alabama and prohibit their positive discussion in Arizona.

- Arizona17 and New York18 introduced legislation to mandate sex education in all school districts.

- New York19 and Texas20 introduced legislation that would require that sex education help pupils develop healthy relationships.

- Arizona,21 Massachusetts,22 Michigan,23 and Pennsylvania,24 introduced bills that contain language about both consent and healthy relationships.

Lawmakers in Florida,25 Georgia,26 Kentucky,27 Mississippi,28 and Washington state29 also introduced legislation to incorporate instruction on consent, dating violence, and healthy relationships into their sex education standards, but the bills did not pass before the end of the state legislative sessions.

Table 1 illustrates which U.S. states, as of May 2019, have enacted or are considering laws to modernize their sex education standards.

Emerging areas

In addition to adding explicit language about consent and healthy relationships, some states are further modernizing their standards by requiring discussion of these topics through the lenses of online conduct and LGBTQ inclusivity.

Digital conduct

As mentioned above, California, Missouri, and New Jersey enacted legislation last year to include discussion of the legal and emotional consequences of sharing explicit material through digital media. Wyoming also already includes standards for “digital citizenship,” noting that “technologies present new risks to their [students’] health and safety, including the dangers of online sexual solicitation” and stating that instruction should be provided on effective electronic communication techniques to reduce risks.30

Educating students about the risks of distributing explicit material online is crucial as teens are sexting, or sending sexually suggestive or explicit messages by phone, at increasing rates. In 2009, approximately 4 percent of 12- to 17-year-olds in the United States had sent a sexually explicit message.31 In 2018, that number had more than tripled.32 And young people aren’t always complicit in the distribution of their own explicit content. In the same study, more than 12 percent of participants admitted to forwarding a sext or otherwise sending an explicit text to others without the permission of the original sender33—something that is illegal in 33 states.34 With more states—such as Kentucky,35 New York,36 and Massachusetts37—introducing legislation specifically targeting the legal consequences of sexting, sex education standards need to catch up to ensure that young people understand the law.

Yet, teaching students how to participate in safe and healthy online discourse is not only legally wise; it is a public health concern as well. Social pressure to engage in these activities can have devastating consequences. In the past decade, at least two teen suicides have been attributed directly to sexting;38 notably, both victims were girls. Compared with boys, girls report feeling more pressure to send explicit content, while also worrying that they will be judged if they do so.39 Such social pressures mean that today, no sex education class focused on consent and healthy relationships is complete without discussing online consent and coercion.

LGBTQ inclusivity

As sex education adapts to reflect modern technology, it also needs to reflect students in the classroom. Only nine states currently have LGBTQ-inclusive sex education,40 and Massachusetts is working to pass legislation on this issue. At least two other states—Alabama and Arizona—are making progress by proposing to remove language from standards that restrict mention of nonheterosexual relationships, which in Alabama require that such mentions be negative and in Arizona prohibit that they be positive. But much more needs to be done to create truly inclusive standards. For example, California recently updated its sex education guidance to help teachers discuss gender identity as early as kindergarten and to give LGBTQ-specific advice about healthy relationships and safe sex.41

The consequences of denying LGBTQ young people the information and tools they need to stay healthy are devastating. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and youth who have had sex with people of the same sex or both sexes are less likely to have used a condom than their heterosexual counterparts.42 The same survey also found that transgender youth were more likely than their cisgender counterparts to report their first sexual intercourse before age 13 and to report not using a condom during their most recent sexual intercourse.43

LGBTQ inclusivity in sex education also has important implications for instruction in consent and healthy relationships. Transgender youth face higher risks of sexual violence than their cisgender counterparts, with 24 percent of transgender youth reporting being forced to have sexual intercourse, compared with 4 percent of cisgender male students and 11 percent of cisgender female students. Twenty-six percent of transgender youth also report experiencing physical dating violence, compared with 6 percent of cisgender male students and 9 percent of cisgender female students.44 LGBTQ youth also face unique forms of coercion such as the threat of being outed, which teachers should include in discussions of consent and relationship abuse.45

Students and female legislators are leading the way

One factor behind the growing momentum for changes to sex education standards may be student activism, as young people have bolstered most of the recent bills that have been proposed and enacted. Students have spoken out about their personal experiences and the difference that better sex education could have made in their lives. Students in both progressive- and conservative-leaning states are working on this issue, demonstrating that progress is possible across the country.

Maryland middle schooler Maeve Sanford-Kelly, for example, channeled her feeling of powerlessness after the 2016 presidential election into action to improve sex education for all Maryland teens.46 “Before we are taught about pregnancy prevention and STDs [sexually transmitted diseases], we have to be taught about consent,” Sanford-Kelly was quoted as saying by NBC News.47 In Utah, high school students Simon Tucker and Mia Chamberlain have been advocating for comprehensive sex education through writing and activism.48 They argue that information about contraception should be the norm in Utah sex education and that students who have a religious objection should have the option to opt out.

In Colorado, high school freshman Clark Wilson testified in favor of a bill that would promote healthy relationships that are free from violence,49 while Caitlyn Steiner, another high school student, started a petition in support of the same bill and has spoken out in its favor.50 In Pennsylvania, meanwhile, high school senior Abby McElroy testified before her local school board in 2018 to speak out against the medically inaccurate sex education lesson she and her classmates received; she is now working with the Pennsylvania General Assembly to develop comprehensive sex education standards.51

In Yakima, Washington, high school student Anna Ergeson has advocated in favor of legislation that would require all students to receive comprehensive sex education that “encourages healthy relationships” and “teaches how to identify and respond to … sexual violence.”52 Ergeson told the Yakima Herald that, “This bill is more important here than it is in any other parts of the state … I know that this is a conservative town, and I don’t think they understand the importance (of comprehensive sex ed)—and the risk of not having it.”53

Finally, in Idaho, many students recently testified against a bill that would have required parents to opt in to sex education for their children.54 Due in part to this activism, the bill died in the state Senate in March 2019.55

Female legislators have also had an outsize impact on this issue. Of the 7 bills updating sex education standards enacted within the past year, women introduced all but 2; women also introduced more than half of the bills to modernize sex education standards that state legislatures are currently considering. More than half of all of the bills’ total co-sponsors are female lawmakers, and freshman women are particularly represented: One-third of all bills currently moving through the legislative process were introduced by women who began their tenures in 2019.56

Female lawmakers have been particularly active in states that have enacted changes to their laws and standards. All four co-sponsors of the bill that passed in Oklahoma were women, and two were newly elected women, despite only 22 percent of the legislature being female.57 Women represented more than half of the co-sponsors of the bills passed in Illinois and Maryland, compared with only 36 percent58 and 32 percent59 of their respective state legislatures last year. Today, women constitute less than 30 percent of state legislatures;60 these numbers make it clear that they have significant interest in and engagement with this topic.

Conclusion

The #MeToo movement, along with the advocacy efforts of students and female lawmakers, has created momentum around including discussions of consent and healthy relationships in sex education standards. Yet, although momentum is positive and states are taking important steps to enact legislation, there is still more work to do in order to truly modernize sex education in every state. Topics of consent must reflect the ways in which today’s young people interact, and discussions about healthy relationships are incomplete if they do not represent a diverse array of relationships.

Additionally, while the analysis in this issue brief focused on the modernization of one area—consent and healthy relationships—it does not purport to make any claims about the many other areas in which many states still have regressive policies such as not requiring information in sex education classes to be medically accurate or requiring that parents opt in to sex education for their children. State and local policymakers must continue to update and modernize sex education standards so that young people of all sexualities and gender identities are equipped with the knowledge they need to make safe, healthy choices when navigating intimate relationships in all contexts.

Catherine Brown is a nonresident senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. Abby Quirk is a research associate for K-12 Education at the Center.