Richie Brown, a North Carolina educator who was a candidate for teacher of the year, is the type of teacher that every principal should want. He was teaching in a high-demand subject area in a low-income school just outside of Wilmington, North Carolina. However, Brown decided to leave the profession last year after six years of teaching, and the reason was simple: He did not earn enough money to support his family.

“I was about to be a seventh-year teacher, and I would be paid the same as I was as a second-year teacher,” Brown told a reporter with television station WWAY, which produced a segment on his departure. Brown and his wife, who is also a teacher, determined that they simply could not support another child with their current salaries.

“I will definitely miss being able to teach those kids,” continued Brown. “But one thing I’m looking forward to is being compensated fairly for one and having a chance to move up in the world.”

Low teacher pay is not news. Over the years, all sorts of observers have argued that skimpy teacher salaries keep highly qualified individuals out of the profession. One recent study found that a major difference between the education system in the United States and those in other nations with high-performing students is that the United States offers much lower pay to educators.

But for the most part, the conversation around teacher pay has examined entry-level teachers. The goal of this issue brief was to learn more about the salaries of mid- and late-career teachers and see if wages were high enough to attract and keep the nation’s most talented individuals. This research relied on a variety of databases, the results of which are deeply troubling. Our findings include:

- Mid- and late-career teacher base salaries are painfully low in many states. In Colorado, teachers with a graduate degree and 10 years of experience make less than a trucker in the state. In Oklahoma, teachers with 15 years of experience and a master’s degree make less than sheet metal workers. And teachers in Georgia with 10 years of experience and a graduate degree make less than a flight attendant in the state. (See Appendix for state-by-state data on teacher salaries. We relied on “base teacher” salaries for our data, which typically does not include summer jobs or other forms of additional income.)

- Teachers with 10 years of experience who are family breadwinners often qualify for a number of federally funded benefit programs designed for families needing financial support. We found that mid-career teachers who head families of four or more in multiple states such as Arizona and North Dakota qualify for several benefit programs, including the Children’s Health Insurance Program and the School Breakfast and Lunch Program. What’s more, teachers have fewer opportunities to grow their salaries compared to other professions.

- To supplement their minimal salaries, large percentages of teachers work second jobs. We found that in 11 states, more than 20 percent of teachers rely on the financial support of a second job, and in some states such Maine, that number is as high as 25 percent. In these 11 states, the average base salary for a teacher with 10 years of experience and a bachelor’s degree is merely $39,673—less than a carpenter’s national average salary. (Note that teachers typically have summers off, and the data on teachers who work second jobs do not include any income that a teacher may have earned over the summer.)

The bottom line is that mid- and late-career teachers are not earning what they deserve, nor are they able to gain the salaries that support a middle-class existence. Think of it this way: Unless the nation’s mid- and late-career teacher-pay issue that teachers grapple with is properly addressed, we are going to have many more Richie Browns.

The issue of low salaries goes well beyond education. As David Madland, Managing Director for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress, has argued, middle-class wages are in a downward spiral in many professions. American families are now taking on more debt than ever before, and our nation’s middle class has become fragile and faces mounting uncertainty. More than that, it seems that for a family to enter the middle class today—and once in, stay there—a household needs at least two sources of income.

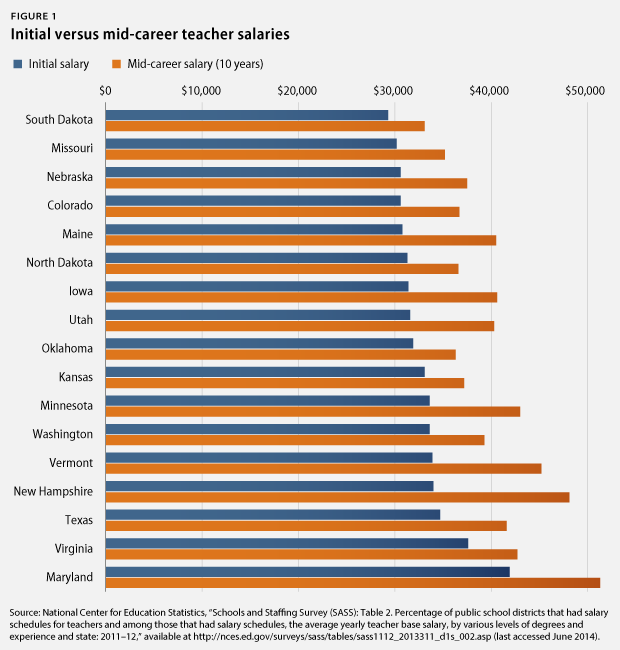

This problem has become particularly acute in education, though, and we found that low mid- and late-career base teacher salaries are an issue in almost every state. In some states, the salaries of teachers seem nothing but paltry; for example, the average salary for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree and 10 years of experience in South Dakota is $33,100 per year. That is well below the state’s median household income of $49,091, and approximately what a printing press operator earns in the state. This also means that a mid-career teacher in South Dakota supporting a family of four can potentially take advantage of seven government assistance programs, according to our research.

Even mid- and late-career teachers in states with some of the highest salaries are grappling with the cost of living. Take California, for example. The average salary for a teacher with 10 years of experience and a bachelor’s degree is $51,400, which is significantly higher than the majority of mid-career teachers’ salaries in other states. Yet this salary is unsustainable in California’s major metropolitan cities. California teachers, including those at the highest step of the pay scale, have low purchasing power when it comes to feasibly affording a home in urban areas. Not only are these mid-career teachers facing limited housing options, but the cost of groceries, transportation, and health care in these areas is also above the national average and taking a toll on teachers’ paychecks.

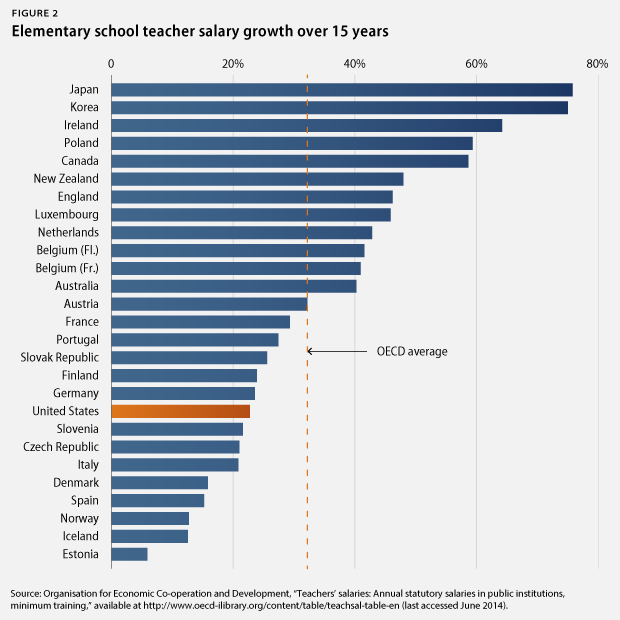

When it comes to teacher pay, mid- and late-career teachers also have much less room to grow their salaries. The median salary for a mid-career sales manager is $101,640, with a median entry-level salary of $51,760. In other words, a sales manager’s salary almost doubles from the time that he or she enters the profession to when he or she reaches the middle of his or her career. On the other hand, teacher salaries only increase by around 25 percent during that same time period. The average starting salary for an elementary school teacher in the United States is $37,595. But a mid-career elementary school teacher earns only slightly more than a new teacher, taking home an average yearly salary of just $46,130.

It does not have to be—and should not be—this way. Many Western democracies take a very different approach to teacher compensation. New elementary school teacher salaries in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, countries increase on average by 32 percent over the first 15 years of teaching, which is almost 10 percentage points higher than in the United States.

Or consider Canada, where a primary teacher’s average initial salary is $35,534. That is slightly less than the average U.S. starting salary of $37,595. But while teachers in the United States have a higher starting salary, Canadian teachers quickly surpass their American peers, with the average mid-career teacher in Canada earning $56,349 per year—almost 60 percentage points higher than their starting salary. By contrast, a U.S. teacher’s salary grows much less during this same time period, which results in a mid-career U.S. teacher earning approximately $10,000 less than his or her Canadian counterpart.

The good news is that some places—including the District of Columbia; Portland, Maine; and Baltimore, Maryland—have begun to address the issue of low mid- and late-career salaries by implementing innovative compensation systems that keep talented teachers in the profession. For example, the District of Columbia’s IMPACTplus teacher-evaluation system provides monetary rewards based on performance and enables teachers in low-income schools to be eligible for the largest bonuses. Shira Fishman, a former TNTP Teaching Fellow, was able to earn a six-figure salary from teaching in a high-need school and receiving a “highly effective” rating two years in a row. And while there are a variety of factors that go into the evaluation of teachers in the District, the end result is that highly effective mid- and late-career teachers such as Fishman can earn top-tier salaries.

Portland takes a slightly different approach than Washington, D.C., with its Professional Learning Based Salary Schedule, or PLBSS, which provides teachers with the opportunity to earn higher salaries by taking classes. The goal of Portland’s salary system is to reward teachers who continuously update their skills. Teachers who take such classes have the potential to increase their salaries by as much as $33,654.

This approach has shown results. For one, the next-generation salary schedule has effectively increased staff interest in professional learning. Other survey data suggest that the new salary structure has improved classroom teaching, with more than 75 percent of Portland teachers saying that the system has contributed greatly or somewhat to improvements in their classroom teaching.

In Baltimore, teachers are part of a career pathway incentive-based pay system whereby they accumulate “achievement units” for demonstrating professional effectiveness. Teachers gain these units through professional development, strong evaluations, and gains in learning outcomes, among other measures. What’s more, teachers in Baltimore can earn substantial incomes, and some educators are eligible to earn more than $100,000 per year.

Increasing compensation alone will not solve the issue of retaining effective mid- and late-career teachers, and to be sure, there are all sorts of reasons why mid- and late-career teachers are frustrated with the profession. Many are upset with working conditions, while others bemoan the lack of meaningful career development. However, as a nation, we need to do far more to attract—and keep—mid- and late-career teachers. In the end, if we truly want to retain top talent in our classrooms, we need to offer top-talent salaries.

Ulrich Boser is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Chelsea Straus is a Research Assistant for the K-12 Education Policy team at the Center.

Appendix