Just one year after several high-profile teacher walkouts began across the United States, teachers in multiple cities and states are once again protesting and going on strike to demand better working conditions and fairer pay.

States have not funded schools at the levels needed to support a high-quality education. Teachers are protesting this chronic disinvestment in education—and they are seeing results. Education funding was a top issue in the 2018 elections, with pro-education candidates winning gubernatorial elections in historically underfunded states such as Wisconsin, Kansas, and Michigan. Elsewhere on the ballot, voters across the country approved 11 out of 15 education funding ballot measures to bring new revenue to schools.

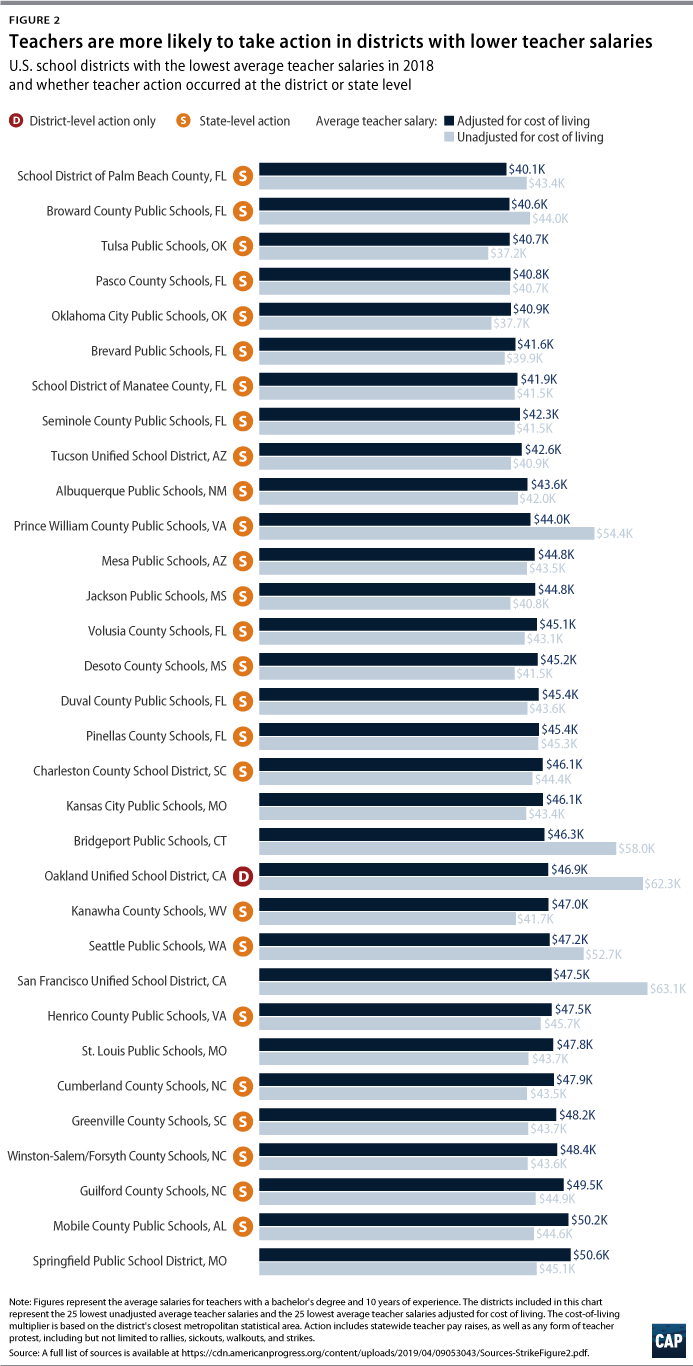

Now, a new Center for American Progress analysis shows that of the 10 states with the lowest average teacher salaries in 2018, adjusted for cost of living, seven have seen recent statewide teacher action in the form of strikes, walkouts, and rallies. In the other three, legislation addressing teacher salaries has been introduced or passed within the past two years. A similar trend exists at the district level: 13 of the 25 lowest-paying school districts in the United States, adjusted for cost of living, have seen teachers take direct action, and another nine districts are in states where teacher or legislative action has occurred. (see figures 1 and 2)

Disinvestment in education is the underlying cause of the 2018 and 2019 teacher strikes

The current wave of local strikes—occurring across Los Angeles, Oakland, and Sacramento in California, as well as in Denver—are different than last year’s statewide walkouts in Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. The 2018 strikes mainly grew from organic teacher actions explicitly protesting low pay and state disinvestment. In contrast, the 2019 strikes have been organized by local unions that are concerned about issues beyond pay and state funding, including rising health care costs, lack of guidance counselors and social workers in schools, and large class sizes.

But despite these differences, the teachers who walked out in 2018 and 2019 do share one underlying concern: their states’ disinvestment in education. When the Great Recession hit, property values plummeted, and local school districts struggled to raise revenue. At the same time, state revenues, which pay for roughly half of K-12 education programs in most states, also dropped, and educational services faced severe cuts as a result. This led to severe cuts in education funding in many states, with most only just recovering more than a decade later.

Some state actions have worsened education funding shortfalls

The recession’s effects on education funding have been magnified in states that have enacted legislation or ballot measures to further restrict educational spending. Similarly, some governors made the policy choice to enact tax cuts for wealthy residents and corporations when state revenue finally recovered, allowing disinvestment in schools to continue far beyond the immediate impact of the recession.

State disinvestment underlies districts’ difficulty meeting the union demands that are prompting this year’s teacher actions. California, where teachers recently went on strike in Los Angeles and Oakland and have authorized a strike in Sacramento, has a history of defunding education. In 1978, Proposition 13 decreased property tax rates and restricted future property tax increases, decreasing the amount of money available for public education.

The state passed a new funding formula in 2013, but by that point, California’s education funding had already fallen to 35th in the nation in per-pupil spending. As of 2018, California’s per-pupil education funding remains below the national average. In some areas of the state where living costs are very high, such as Oakland, disinvestment in education has led to high teacher turnover and has put housing out of reach for local teachers. California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) this year proposed significant increases to the state’s K-12 education budget, but they were not targeted toward teacher salaries. It remains to be seen whether they will make it through the state’s Legislature and into law.

Colorado, where Denver teachers walked out last month, spends less per student than most states with similar levels of wealth and economic activity. A 1992 state law, the Taxpayer Bill of Rights amendment, is partly to blame; the legislation reduced the total possible revenue for schools. And due to a 15.6 percent decrease in education spending from 2009 to 2017, the state made the second-largest cuts in the nation during that time period.

Disinvestment has consequences for teachers, students, and schools

Defunding education has had serious consequences around the nation—and these consequences are only growing. In many states, teachers with 10 years of experience have annual salaries of less than $50,000, often making them eligible for federal benefit programs such as the Children’s Health Insurance Program or requiring them to work additional jobs during nights and weekends. In Colorado, according to the authors’ analysis of Schools and Staffing Survey data, more than one-fifth of teachers reported working a second job in 2012—the 13th-highest rate for teachers in the nation.

But salaries are not the only piece of the puzzle; states’ failure to invest in their public education systems triggers additional consequences. Teachers are expected to pay out of pocket for even basic classroom supplies and materials, and due to a lack of enough staff to ensure reasonable class sizes, they are sometimes forced to teach in classrooms with more than 40 students. Moreover, instead of working in buildings that are up to modern standards, many teachers must work in poor conditions, including uncomfortable temperatures and substandard air quality and lighting.

These conditions are affecting teachers in states that are experiencing teacher protests and strikes, such as California, where teachers reported spending an average of $585 annually on classroom supplies without reimbursement—the highest amount in any state. According to 2015 data, California also had the largest pupil-to-teacher ratio of any state, with 23.9 pupils per teacher. Low salaries only exacerbate these burdens.

When states persistently underinvest in education, schools lack sufficient funds to ensure that students’ classrooms are conducive to learning; not only do teachers’ working conditions suffer, but students are harmed as well. In particular, black and Latino students, who make up large proportions of school districts such as Los Angeles and Oakland, are more likely to attend schools where most of their classmates are low-income. Schools such as these tend to rely more heavily on state funding, making state disinvestment doubly problematic in these locales.

Conclusion

The movement for better working conditions and higher pay for teachers is transforming the way policymakers think about teacher pay and education funding more broadly. In the 2018 elections, governors across the country touted their plans on teacher pay and education, and investments in education feature prominently in many states’ budget proposals. The most recent teacher strikes should put an end to any remaining excuses for underpaying teachers. While leaders in many states have made a good faith effort to increase education funding after the Great Recession, in others, current funding levels are still too low to support quality education for U.S. children. State policymakers who haven’t already should reinvest in education programs—because teachers deserve fair pay, schools deserve more resources, and students deserve a better chance at success.

Lisette Partelow is the senior director of K-12 Strategic Initiatives at the Center for American Progress. Abby Quirk is a research associate for K-12 Education at the Center.