Introduction and summary

The current economic crisis in the United States requires a renewed commitment to investing in rural communities in order to ensure that they have a prominent place in this country’s future. Given the changing nature of the rural economy, the lack of upward mobility in many rural communities, and the persistent gap in unemployment and poverty rates between metro and nonmetro counties, the United States needs to overhaul its current approach to rural development and create a new framework that builds resilient rural communities. This new framework must call for a complete change in mindset about what constitutes rural America, the assets within these diverse communities, and the struggles they face. Rethinking rural development policy will also require investing in these communities from the bottom up instead of the top down, empowering them to identify and leverage their existing assets and knowledge and to promote homegrown economic opportunities.

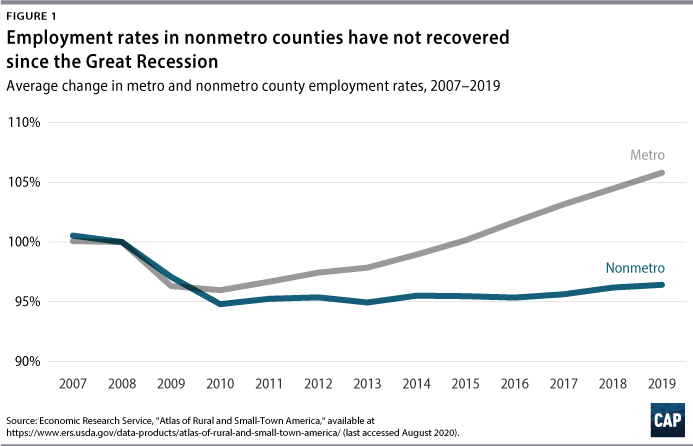

As news outlets heralded record sustained economic growth in the United States following the Great Recession, many Americans still struggled to see evidence of this recovery in their own communities. In fact, though metropolitan areas rebounded, nonmetropolitan counties had yet to achieve pre-2008 levels of employment when the COVID-19 crisis hit the world economy. While some of the gap in employment is related to shrinking and aging rural populations, the gap in unemployment rates has continued to widen over recent years.1

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting economic crisis further exposed the vulnerability of rural communities. COVID-19 hit rural America hard for a variety of reasons—including the closure of rural hospitals in recent years; deep poverty; and the failure to protect vulnerable food-chain workers from infection, to name just a few examples.2 Moreover, rural communities often struggle with accessing federal resources. This phenomenon was evident in the coronavirus pandemic response, which gave states discretion for how they would aid their rural communities while metro areas received direct aid.3 Meanwhile, rural businesses have encountered difficulties accessing Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, in part because of the failure of the Small Business Administration to provide guidance requiring banks to prioritize businesses in underserved and rural areas as the PPP proscribes in its text.4

While rural areas may lag the nation in population growth and productivity, these metrics do not capture the full picture.5 Decades of measuring economic value through gross domestic product (GDP) and conflating growth with the stock market have encouraged the corporate extraction of wealth out of rural areas.6 This mindset has hollowed out rural communities and institutions while enriching shareholders.

Draining rural areas of their resources and wealth, however, has made the overall economy less resilient. In mid-August, the rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases in rural counties exceeded that of metropolitan counties, particularly in areas key to food supply, such as meatpacking plants in Iowa and Missouri as well as other Midwestern states. These outbreaks have disrupted supply chains across the country and overburdened rural hospitals.7 As the pandemic has shown, this country’s economy cannot withstand external shocks until it ensures that all communities have access to the same services and opportunities.

Throughout history, lawmakers have struggled to keep up with rural areas’ evolving economic realities and achievements. Previous attempts to invest in rural America—such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act, passed in 1933—have often conflated farming with the broader rural economy while simultaneously excluding and exploiting rural people of color. This history is reflected in modern rural development policy, which focuses disproportionately on agriculture while underinvesting in the full range of diverse rural American communities.

For example, the lead agency in charge of rural development is housed in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), even though only about 1 in 5 nonmetro counties are dependent on agriculture.8 Currently, rural development projects span 16 agencies but lack any central strategy or structure.9 A real federal commitment to rural America requires founding a new, well-funded Rural Opportunity Administration solely devoted to rural economic development that can unify these programs and implement them in a cohesive manner. This bold change would signify a meaningful commitment to modern rural America.

Although agriculture, manufacturing, and mining have been the mainstays of the rural economy, due to increasing concentration of industries creating firms with extreme market power, this is no longer the case. In fact, the largest sector in rural communities in terms of employment is the service sector, specifically in health, education, and social services.10 Therefore, an economic agenda for rural America must include a plan to safeguard key services and ensure that any jobs created are high quality. The contributions of rural America’s manufacturing and agricultural production are invaluable to the economy, but they must be reimagined in order to circulate wealth through these communities and to promote vibrant, sustainable local economies, instead of extracting profits that merely benefit distant shareholders. Policymakers must ensure that rural communities hit hard by changing economic and environmental trends have the resources and support they need to chart a new future and create high-quality, sustainable jobs.

This report proposes that federal lawmakers take the following actions:

- Create a specialized and well-resourced Rural Opportunity Administration whose mission would be to foster economic growth and vitality.

- Shift the rural development paradigm from a top-down approach to a bottom-up strategy by directly funding rural communities and facilitating an asset-based approach to rural development.11

- Strengthen rural labor markets through federal laws to raise wages, expand benefits, promote collective bargaining, and strengthen enforcement of worker protections.

Geographic inequality and economic mobility

Geographic inequality has emerged as a central economic and political problem in recent decades. Since the 1980s, the regional convergence of per-capita income sustained since 1930 has halted completely.12 By some measures, geographic inequality could even be increasing. From 1980 to 2013, the share of the U.S. population living in metropolitan areas that lie on either extreme on the income distribution rose from 12 percent to 30 percent.13 Geographic inequality is driven by a number of factors, including growing income inequality, the movement of wealthy and high-earning Americans to urban centers, increased monopoly power, and the loss of manufacturing jobs due to globalization and trade agreements that have failed to protect workers.14 Moreover, the erosion of banking regulations—such as the Glass-Steagall Act—has driven banking consolidation, reducing investment and credit access in some rural areas.15

Geographic inequality, also referred to as regional divergence, raises grave economic and political concerns. It is unhealthy for the country to have nearly three-quarters of its employment growth concentrated in major metropolitan cities—and to have many small towns that have yet to reach pre-recession employment levels.16 Regional divergence is also a social injustice, as the hyperconcentration of growing sectors in large cities limits opportunities for economic mobility among communities of color in both rural and urban areas.17 This not only depresses national economic growth but also sends a message to rural Americans that if they want to pursue economic opportunity, they have to abandon their communities and move to major cities.18

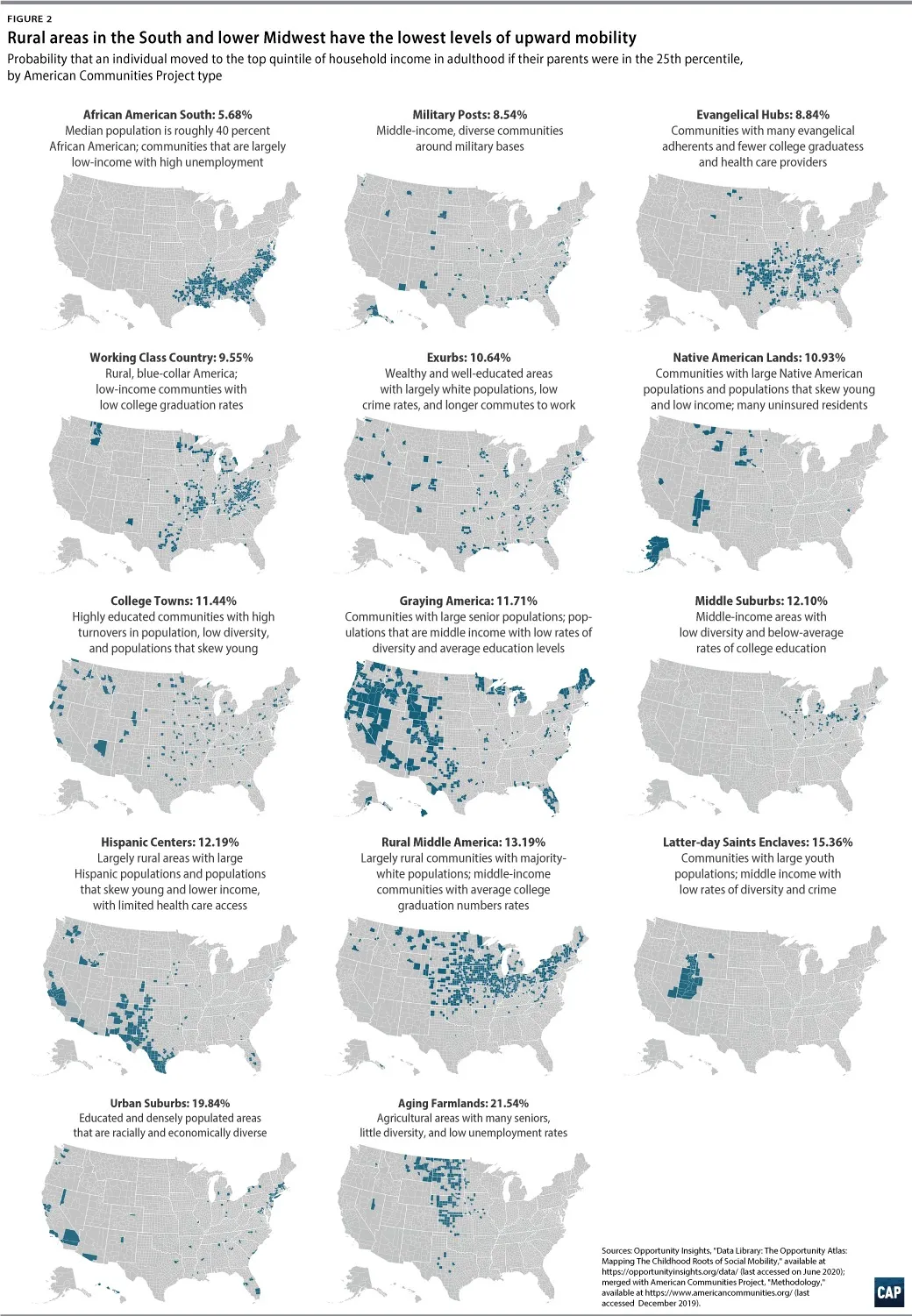

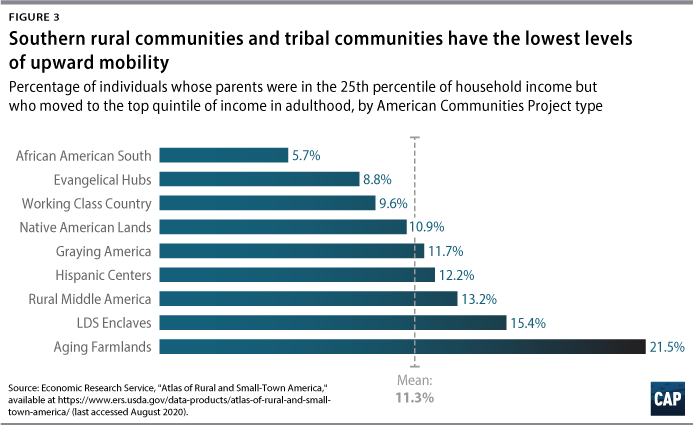

Upward economic mobility—defined as the probability that a child in the bottom 25th percentile of income reaches the top 20th percentile of income as an adult—varies widely across regions and county types.19 Using the classification system from the American Communities Project, which groups counties by common economic, geographic, and demographic characteristics, the authors compare economic opportunity across distinct types of rural communities.20 The results, shown in the figures below, highlight deep disparities in economic mobility between different kinds of rural communities.

The geographic patterns of upward mobility reflect the geographic nature of some systemic inequality—the intentional disenfranchisement of particular groups, usually based on race. Racial wealth gaps caused by systemic inequality have persisted throughout American history.21 However, until recently, policy researchers have not fully examined the issue of systemic inequality in the context of rural communities. Yet rural communities bear the mark of structural discrimination as clearly as any city.22

Native American communities, for example, face enormous hardship resulting from the brutal colonization of their lands by European settlers. Those who were not murdered through systematic genocide were forced to relocate to undesirable territory and cede large portions of their land.23 The General Allotment Act dispossessed tribes of two-thirds of the 138,000,000 acres they held in 1887, breaking up landholding among households and individuals and putting the remainder up for sale to white homesteaders.24 Some of the land allotted to Native Americans through this law is still held in individual trusts that manage the use of the land on behalf of the native owner and beneficiary.25 Through this system, trustees lease the land for grazing, logging, mineral extraction, and more—receiving payment and then disbursing funds through an Individual Indian Monies (IIM) account.26 This system, paternalistic and extractive at its core, has been chronically mismanaged, resulting in a class-action lawsuit brought by IIM beneficiaries demanding restitution for funds that were improperly withheld from their accounts; the plaintiffs eventually won a settlement of $1.4 billion in 2012.27 The case of IIM accounts and allotments perfectly illustrates how a history of racism has established an enduring extractive relationship between rural Americans of color and the rest of the country.

Rural Latinx communities in the United States, whose population grew by almost 50 percent from 2000 to 2010, also face serious structural barriers.28 Latinx workers are much more likely than non-Hispanic workers to work in the restaurant industry or the agricultural sector—where jobs often pay less than the minimum wage.29 About half of all farmworkers in this country are Hispanic, according to the USDA.30 This occupation poses many hazards yet lacks many of the federal protections afforded to other workers, such as the right to form a union and collectively bargain.31 The insufficient federal protection of this intrinsically rural occupation, in which Latinx people are overrepresented, is just one example of how federal laws neglect key rural communities.

Lower levels of upward mobility, while not limited to one particular geographic area or classification, are concentrated in the South, where decades of anti-worker policies such as “right-to-work” laws—which seek to limit the formation of unions and restrict economic opportunities for African Americans—have created a low-wage labor market that harms all residents in the rural South.32 In addition, Black farmers have been driven off their land by systemic discrimination at the USDA that continues to this day.33

Given the regional divergence that has been occurring since the Great Recession, rural communities rightly feel left behind. Policymakers have long celebrated the virtues of rural life and, consequently, have endeavored to maintain vibrant rural communities. Unfortunately, the very institutions erected to help foster a prosperous rural America often exclude large swaths of rural residents. For example, the USDA, sometimes known as the “Last Plantation,” has a long record of proven discrimination against Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people.34

The history of rural development policy

U.S. history shows that federal rural development and rural anti-poverty policies have generally been unfocused and intermittent, consisting of temporary influxes of investment and short-lived programs. Generally, these efforts have favored agricultural communities over nonfarm rural communities and have failed to evolve alongside the changing rural economy.

Though the USDA dates as far back as the Lincoln administration, modern rural development policy was born during the Great Depression, which hit farm communities earlier and harder than the rest of the country due to the Dust Bowl and low commodity prices after the end of the First World War.35 In addition to farm supports instituted under the Agricultural Adjustment Act to prop up farm income, the New Deal included several programs aimed at stimulating economic growth through public works programs that benefited rural Americans on and off the farm. The Tennessee Valley Authority, established by Congress in 1933 at the request of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the Rural Electrification Act of 1936 struck brand new ground in rural development policy by investing directly in public utilities as a job creation strategy.36

Aside from the public works programs of the New Deal, federal rural poverty programs were primarily aimed at the agriculture sector and farmers in particular due to the largely agricultural nature of rural America at the time.37 For example, the main anti-poverty agency of the New Deal USDA was the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA), which, as the name implies, was established to finance and insure farm households.38 This program was not expanded to include nonfarm households until 1961. Moreover, farm payments largely went to white landowners instead of sharecroppers of tenant farms, resulting in the mass displacement and dispossession of African American farmers in the South.39

Though rural programs tended to focus primarily on farmers, the New Deal’s larger economic vision—encapsulated in the Second Bill of Rights, which included the right to housing, education, and a quality job—laid important groundwork for preparing rural America for the coming shift away from agriculture.40 The New Deal’s landmark federal labor laws expanded worker protections to countless rural Americans. However, many New Deal labor policies, including the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established the first federal minimum wage, excluded people of color by leaving out farmworkers and domestic labor.41 To this day, farmworkers are not covered by the National Labor Relations Act, the landmark New Deal law that bestowed most workers the right to form unions and collectively bargain.42 The exclusion of farmworkers and farmers of color meant that rural Americans of color were largely discounted by the New Deal.

During the Great Depression, the federal government’s emphasis on farm policy was understandable: According to the U.S. Census of Agriculture, about 80 percent of the country’s rural population lived on farms in 1920.43 However, the economics and demographics of rural America changed rapidly in the following decades, and federal policy was slow to catch up. By 1940, only about one-half of the rural population lived on farms.44

Despite changing economic realities in rural America, however, anti-poverty programs focused primarily on aiding low-income farmers during the Eisenhower administration.45 In a 1967 report titled “The People Left Behind,” the National Advisory Commission on Rural Poverty noted the dissonance between federal policy and rural reality, writing: “Some of our rural programs, especially farm and vocational agriculture programs, are relics from an earlier era. They were developed in a period during which the welfare of farm families was equated with the well-being of rural communities and of all rural people. This no longer is so.”46

At the beginning of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” more than half of all Americans living in poverty resided in rural areas.47 Due to the heavy focus on rural communities during the president’s trip through several states to raise awareness of American poverty, as well as the leadership of Agriculture Secretary Orville Freeman, most of the Economic Opportunity Act’s (EOA) programs addressed rural challenges.48 Title III of the act created a program to loan money to rural residents for the purchase of land, capital investments in a farming operation, and the incorporation of cooperatives and businesses.49 Significantly, the EOA also expanded funding opportunities to tribes by allowing agencies other than the Bureau of Indian Affairs to disburse funds to tribes.50

The act’s more general provisions also made large investments in rural areas, directly and indirectly. A sizable portion of Job Corps projects involved conservation and construction projects on and around public lands, enhancing a crucial asset to rural communities.51 Meanwhile, Title II granted states money according to their need in order to fund local projects through Community Action Programs; it also stipulated that such programs should receive equal funding regardless of whether they were rural or urban.52

The War on Poverty’s emphasis on rural areas was a departure from the previous approach, which viewed the rural economy and the agriculture sector as one and the same. Since then, rural policy has expanded into countless programs across several agencies.

Despite the sprawling nature of federal rural policy, however, it remained housed in the USDA. In 1973, rural development was formally incorporated into the farm bill—a practice that has continued to this day.53 Since then, rural development and farm policy have remained inextricably linked, with the Rural Development Policy Act of 1980 designating the USDA as the lead agency for coordinating rural development.54

Today, the farm economy makes up about 10 percent of overall rural employment overall, as discussed in CAP’s “Redefining Rural America” report, and rural economies are generally more reliant on the service sector.55 Unfortunately, federal rural policy still puts disproportionate focus on agriculture because of the path-dependent nature of policymaking—the manner in which investments in certain agencies and programs tend to reinforce that focus.56 A 2016 Congressional Research Service report notes that agriculture’s role in the rural economy has been shrinking for decades, but in many ways, rural development remains synonymous with agriculture. In fact, “[a]lthough over 90% of total farm household income now comes from off-farm sources, farming, and agriculture more generally, remain the major legislative focus for much of congressional debate on rural policy.”57

The current state of rural development policy

U.S. rural policy does not have a stated goal or a unifying framework. There are 88 programs that target rural economic development, and these programs are administered through 16 federal agencies.58 While the USDA is formally designated as the lead agency, the scope of rural development reaches far beyond its capacity.

This report presents the major federal players in rural economic policy, illustrating both the size of the task at hand and the necessity for a more unified approach. While the Agriculture Department’s role in rural development was natural during the first half of the 20th century, the shift in rural employment away from agriculture—and manufacturing to a lesser extent—calls for a rethinking of the country’s approach to investing in rural America.

USDA Rural Development

The Rural Development office at the USDA leads the federal effort to promote rural well-being by disbursing guaranteed and direct loans as well as grants to rural organizations, businesses, and individuals. By the end of fiscal year 2019, the office had more than 51,000 loans in its portfolio,59 and its total outlays for 2019, excluding payroll, totaled $2.7 billion.60 Including direct and guaranteed loans, which make up the vast majority of Rural Development programs, the total programmatic level weighs in at about $37.7 billion.61

Rural Development is divided into three main programs: the Rural Utilities Service (RUS), Rural Housing Service (RHS), and Rural Business-Cooperative Service.

The RUS, established in 1936, was created to electrify rural communities during the Great Depression.62 Today, it carries on that legacy by supporting projects, in partnership with businesses and/or local governments, to expand and improve the delivery of water, electricity, waste management, and other key infrastructure and services.

Established in the Housing Act of 1949, the RHS is the successor to the FmHA; it supports affordable rural housing by lending to individual homebuyers, providing direct rental subsidies, and lending to developers building housing in rural areas. The program makes up the lion’s share of the guaranteed and direct loans sponsored by Rural Development and houses the Community Facilities Program, which provides grants and loans to build or maintain essential facilities such as health clinics. Yet despite its lead role in rural policy, the RHS is one of the many programs that falls outside of the farm bill, illustrating the scattered nature of rural programs.63

The Rural Business-Cooperative Service offers small loans to small and medium-sized enterprises and would-be entrepreneurs to finance their expansion with the goal of job creation and innovation. It also provides loans and grants to private and public programs that supply technical assistance, training, and mentorship to small-business owners. Additionally, the Rural Business-Cooperative Service houses a program that provides grants and loans to businesses and farms to install energy-efficient or environmentally friendly technology.64 This program provides crucial support to local businesses, which are increasingly crowded out of rural communities by chain discount and “big-box” stores.

Selected rural programs and services housed within the U.S. Department of Agriculture

Rural Utilities Service

- Electric and Telecommunications Direct Loans

- Water and Environmental Loan Guarantees

- Rural Broadband Direct Loans

Rural Housing Service

- Single-Family Housing Direct Loans

- Single-Family Housing Repair Loans

- Rural Rental Housing Loan Guarantees

- Community Facilities Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees

Rural Business-Cooperative Service

- Business and Industry Loan Guarantees

- Intermediary Relending Program

- Rural Economic Development Loans

- Rural Microentrepreneur Assistance Program65

Rural Development programs provide vital services to communities, but they alone cannot address the systemic problems facing rural America. These loans and grants are awarded on a competitive basis and are frequently oversubscribed, pitting rural communities against one another to pay for basic necessities such as affordable housing.66 The longer-term commitments to partners under these programs run about five years and address one discrete problem without addressing the larger context and intersection of problems and structural issues. Rural communities deserve a more comprehensive and prolonged commitment to and investment in their future.

Federal regional commissions

Regional commissions are another key player in rural economic development, taking a more strategic and wholistic approach to stimulating rural economies. Economic development agencies are partnerships between federal, state, and local governments, whose objective is to tackle economic distress by formulating strategic development plans. Funds are overseen by appointees from each level of government and are allocated to projects by multicounty local development districts according to these plans. Administrative costs are shared by the states and the federal government, but the programs themselves are federally funded. The largest projects undertaken by these organizations are typically related to infrastructure, such as water, sewer, or transportation.

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is the country’s oldest regional commission, established in 1965 as a direct response to the rural poverty highlighted by the Johnson administration. Within ARC, there are 73 local development districts—multicounty organizations that serve as the local eyes and ears of the ARC and as a conduit of ARC funds. ARC has designated counties at varying levels of economic distress and funding priority according to unemployment rates, per-capita income, and poverty rates. From 2008 to 2019, federal funding for ARC increased 126 percent, in part because of growing efforts to help coal communities.67

ARC proved to be a popular model, inspiring the creation of several subsequent commissions. For example, the Southeast Crescent Regional Commission, created by the 2008 Farm Bill to address economic challenges in the Black Belt, covers 384 counties across seven states. Other notable regional commissions include the Denali Commission, which serves rural Alaska, and the Southwest Border Regional Commission.68 Meanwhile, the Delta Regional Authority (DRA) was established in 2000 to promote economic development in Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. But while 234 of the DRA’s 252 counties are considered distressed, the commission only receives about a sixth of the funding that ARC receives.69

The strength of these commissions comes from the regional strategy and the involvement of all levels of government. For example, the Northern Great Plains Regional Authority—covering North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, and Minnesota—conducted a comprehensive study of the economic challenges and assets in the region.70 And in 1997, the commission published a detailed development plan consisting of 75 recommendations addressing business development, international trade, value-added agriculture, telecommunications, health care, civic and social capacity, and transportation and infrastructure.71 This strategy took a wholistic view of rural development, providing valuable lessons for the future of rural policy.

Economic Development Administration

Another key vehicle of place-based investment is the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA), an agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce whose mission is to spur locally relevant innovation and entrepreneurship in order to help communities compete in a global economy.72 Conceived in 1965, the EDA was established to assist both rural and urban communities that lagged the nation in economic growth. Today, the EDA has regional offices in six major metropolitan cities; these offices enjoy relative autonomy in the disbursement of grants.

Over the past several decades, the EDA’s initial focus on infrastructure and public facilities shifted to investment in research and development and innovation.73 In 2010, it created the Office of Innovation and Entrepreneurship to support what it termed “high growth” entrepreneurship. Part of this model focused on directing funds to research universities, which are usually deemed innovation hubs. Unfortunately, given the emphasis on high growth and the competitive nature of grantmaking, this left some rural places out of the running. For example, the focus on tech innovation as a key strategy for economic growth has left out economies that lack high-speed internet. While the EDA does prioritize geographic diversity in its awards for programs such as Build to Scale, rural communities still struggle to compete for funding. Certain criteria, such as matching fund requirements, exclude rural communities from programs, even though such requirements are facially neutral.74

Policymakers must broaden their idea of what constitutes innovation. For example, innovation should include incubators for cooperative businesses that provide services such as feasibility analysis and business plan development.75 Economic development should include programs such as partnerships with community colleges to increase educational attainment and strengthen vocational training.76 As long as it is understood that innovation is not synonymous with technology or only limited to tech companies, rural communities can thrive.

Recommendations

Rural America deserves a comprehensive and sustained commitment from the federal government that promotes economic growth by building out the middle class and giving communities the resources and autonomy to chart their own futures. The changing realities of rural America demand an economic framework that is not constrained by stereotypes, but rather embraces the diversity of rural communities and economies.

This report outlines three policy recommendations that aim to revitalize rural communities by elevating rural policy in an administration, growing wealth from the bottom up, leveraging rural areas’ assets, and directly investing in existing residents.

1. Raise the profile of rural investment

As outlined in previous reports,77 rural America encompasses a wide swath of people, industries, and histories. Any successful policy framework must reflect that. In addition, the effects of federal policy should account for how it would play out in rural communities—an analysis that is often missing. A few years after the Great Recession, policymakers engaged in austerity measures,78 cutting government spending before the economy had reached full employment, which did not allow for rural areas to fully recover.79 Therefore, the United States needs a structure that elevates rural issues to ensure that they are at the forefront of policy debates and that the full diversity of rural America is considered.

Creating a new Rural Opportunity Administration

Administering economic development programs is just one small part of the USDA’s numerous responsibilities. The department is charged with regulating, supporting, and monitoring a $133 billion sector, collecting extensive data, and conducting economic analysis and scientific field research.80 Of the eight undersecretaries at the USDA, seven are dedicated to food and agriculture-related areas and just one is dedicated to rural economic development.81 As discussed in this report, the relationship between the USDA, the farm bill, and rural development has resulted in a rural policy framed within the limited context of agricultural communities that has generally deprioritized rural investment in favor of programs geared toward the agricultural sector.

This proposal recommends reconstituting Rural Development as an elevated and prominent administration: the Rural Opportunity Administration (ROA). While the new administration would remain formally within the USDA, its Senate-confirmed commissioner would be given new eminence and added independence to recognize the expansion and heightened importance of the agency’s mission. Much like the Food and Drug Administration within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Internal Revenue Service within the U.S. Treasury Department, elevating the status of Rural Development to that of an administration would support its ability to have a prominent voice on policy and drive the necessary changes to rural investment across the federal government.82 Importantly, it would also signify a significant and lasting commitment to closing the gap between rural and urban quality of life.

The mission of this new ROA would be to advance rural health, education, and opportunity; promote economic vitality; and fight poverty in rural communities. Among other priorities, the ROA would have the goal of cutting the rural poverty rate by 90 percent by 2040—carrying out this mission by facilitating local investment, supplying key services, and tackling structural racism. The administration would be armed with a significantly increased budget commensurate with its enhanced responsibilities and the scope of the challenges rural America faces.

In part through its leadership role on a reconstituted White House Rural Council,83 the ROA would be tasked with coordinating rural development programs from across all federal agencies and providing a steady stream of significant funding and strategic and technical support for rural communities—beyond piecemeal, ephemeral, competitive grants. In doing this, the ROA commissioner would be charged with coordinating with other agencies, such as the EDA, as well as relevant regional authorities. The ROA would also provide administrative recommendations for other agencies to remove barriers preventing rural communities from accessing those agencies’ programs.

To provide much-needed technical assistance for grant-seeking entities and help craft strategic development plans that cut across county lines in coordination, existing regional commissions—such as the DRA—would retain relative autonomy but be formally subsumed within the ROA structure with the goal of providing more consistent funding to those communities while also tapping an existing structure to connect local stakeholders with federal officials. The ROA would take an asset-based, wealth-building approach to community development by investing in local people, institutions, and firms—and by building on the wisdom of homegrown development hubs and community institutions such as broadband cooperatives.84 The administration must connect with local governments, nonprofits, and businesses because they can speak to local concerns given their intimate knowledge of communities, bridge gaps across silos, and encourage collaboration, among other useful strategies.85

In addition to administering rural development programs, the ROA would be tasked with developing a data infrastructure that would collect rural-specific data and conduct and fund research and analysis in service to rural communities. Working closely with the Economic Research Service at the USDA, the ROA would contain a policy and research unit that would conduct and fund research focused on the myriad topics beyond agriculture that are essential to rural prosperity, with an emphasis on economic mobility in rural areas. Its duties would include collecting comprehensive data about rural areas, including metrics beyond economic indicators such as quality of life.

This office would also evaluate the effectiveness of different programs and policies in improving outcomes and advancing prosperity in rural America. Currently, not enough data on rural America are collected to fully inform policy decisions.86 Similar to policy and evaluation units at other agencies, such as HHS, the policy and evaluation office would be an internal think tank that plays a vital role in enabling the commissioner to develop and make recommendations for how to improve rural policy, with a focus on racial equity and low-income communities. Data are also important for combating systemic inequality, as analysts cannot highlight racial disparities in outcomes if data disaggregated by race and geography do not exist.87

In order to ensure the agency’s commitment to racial justice and move the rural policy framework toward one that addresses structural racism and other barriers to opportunity, the ROA would have a directive to be proactively inclusive of marginalized, historically underserved, and persistently left behind rural communities. Moreover, it would be empowered to affect this directive using the most cutting-edge analytics and tools and be mandated to engage in regular public reporting and accountability. The ROA would also work closely with the policy and research unit as well as the local community outreach offices to monitor and conduct outreach to areas of persistent poverty and declining economic outcomes. Key indicators for those areas would be mapped against distribution of program participation and funding—all broken down by race and other key demographic variables. It will be critical to ensure that adequate resources and attention are given to tribal communities; and in order to support the nation-to-nation relationship, the administration will need to closely coordinate with the Bureau of Indian Affairs at the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Reinstating the White House Rural Council with a focus on economic opportunity

To uphold the commitment of the federal government to rural communities, the president must reestablish the White House Rural Council. This council, formed during the Obama administration, was made up of the heads of most of the major agencies and led by the secretary of agriculture.88 It promoted collaboration across agencies and helped prioritize rural communities in programs outside the USDA. Yet the Trump administration dissolved the White House Rural Council, replacing it with the Task Force on Agriculture and Rural Prosperity.89 Unlike the White House Rural Council, however, this task force does not include any representatives or officers from the White House, demoting its significance and undermining its impact across the administration.90

Rural communities must have a seat at the table within the White House. That is why reinstating the White House Rural Council, with a focus on economic opportunity, is crucial to elevating rural issues and forming an ongoing presidential commitment to rural economic development.

The reconstituted White House Rural Council should be structured similarly to the original but with a new subcommittee focused on economic development and chaired by the head of the Rural Opportunity Administration. In addition, the U.S. Domestic Policy Council staff member coordinating the council should be dual-hatted with the National Economic Council. This structure would be modeled on the dual hat worn by the White House lead on international economic policy, ensuring the prominence of economic issues in the council’s work and bringing rural issues back to the priorities of national economic policy development.

With key White House staff, the council would be charged with ensuring that all agencies consider the impacts of policy and programs on rural people, places, and firms, while also driving innovative presidential priorities to improve the state of rural America. The president should issue an executive order that requires relevant federal economic development agencies to conduct analyses to ensure that their programs do not unfairly exclude distressed rural areas or reinforce racial or regional disparities. The findings of these analyses should form the basis of an initial report and inform future coordination efforts between agencies. Additionally, within a year of its creation, the president should direct the council to prepare a comprehensive report laying out a six-year vision for rural investment, with recommendations and an action plan for how rural development can help reach national goals of reducing poverty, improving health outcomes, greening the economy, and more.

2. Build resilient communities by supporting grassroots investment

A major overhaul of federal investment in rural America is long overdue. The current landscape of grants and federal aid to rural communities primarily takes a top-down strategy toward economic development. It largely consists of debt-based projects and piecemeal, one-off, competitive grants. Distressed nonmetro counties in particular are less likely to benefit from guaranteed loan programs.91 The applications for these programs require technical expertise unavailable to some communities and, in some cases, take years to actually yield a check. Moreover, the use of the money is, at times, overly prescriptive, denying communities the chance to engage in creative problem-solving. By restructuring these competitive grants and supplementing them with reliable and flexible funding streams, the ROA can better equip communities to invest in their existing assets and solve their unique problems.

The ROA would streamline the application process for competitive grants and loans by requiring just one application for similar programs previously under Rural Development. For example, if a town were looking for affordable housing assistance, it would only submit one application to be eligible to receive from the Rural Housing Service the whole suite of ROA grants and loans that could address affordable housing in the area. Moreover, the ROA should seek to harmonize the application process for its competitive grants with those at other agencies, including by seeking to bundle together grants across agencies into larger rural-specific funding opportunities with a single application. In some cases, it may make sense to transfer rural-specific grants at other agencies to the ROA for administration. This would greatly reduce the burden on nonprofits or local governments looking to tap into federal resources.

Another major barrier that must be removed is matching fund requirements. For distressed communities, coming up with funds to match federal investment is nearly impossible and, in many cases, should not be required. These steps, in combination with technical support for application writing, would remove many of the barriers that rural communities face when applying for federal aid. This reorganization must be accompanied by a significant increase in appropriations to these programs in order to ensure that streamlining programs does not come at the cost of the communities they serve.

Congress must mitigate the barriers to grant and loan programs and augment them with dedicated funding to rural communities that has the flexibility to empower them to invest in the services they know they need. The ROA would provide streams of guaranteed funding to communities that need support in order to bring their ideas to life or to provide basic services. In creating these programs and trusting localities with flexible, dependable funding, the ROA would move away from a top-down approach to rural development and toward one focused on local decision-making.

Creating a participatory grant program

One specific way the ROA could promote an asset-based approach to community development is by creating a program for participatory grantmaking—based loosely on the practice of participatory budgeting. Participatory budgeting is a process whereby community members get to provide input on how to use a portion of a city or county’s budget through a public forum or even a vote. For example, the city of Durham, North Carolina, committed a total of $2.4 million to projects developed by community members and vetted by experts, and these projects were then voted on by the public.92

A participatory grant program would provide communities with a lump sum of money that would be spent in accordance with public input. This process empowers people to use their direct knowledge to leverage their existing community assets to invest in their communities. Participatory grantmaking would help to ensure that resources are allocated in a more democratic and transparent way when compared with decisions made by local officials who may be less accountable to their constituents—be it due to socioeconomic powers or a history of voter suppression that continues today.

Rural communities across the country have already taken their destinies into their own hands to develop innovative programs; they simply lack the resources to build capacity. The ROA should invest in these communities by providing each nonmetro county with a guaranteed—noncompetitive—annual grant. The size of these grants should be determined through a universal formula that is based on a number of factors, including poverty rates and educational attainment, but not unduly constricted by population.

The ROA would create a local board for each county made up of a mix of elected community members and one state, one local, and one federal ROA official. This board, through a public process that includes public hearings and debates, would develop a plan for how it would spend the funds—whether on new or existing programs and services. To the greatest extent possible, these local development boards should have a predictable stream of federal funding that is adjusted for the cost of inflation in order to ensure that the community can build sustainable, dependable programs.

In order to ensure that the grants are serving public needs, the ROA should supply a list of qualifying investments and programs.

The menu of possible services and programs may include:

- Clean energy transformation

- Workers’ centers

- Child care centers

- Legal clinics

- Health clinics

- Small-business incubators

- Continuing education and language programs

The grants should include living wage and other high-road employment requirements for all jobs created or supported through the participatory grant spending. They should also be evaluated by the ROA research arm to analyze the effectiveness of different program designs and to verify that they result in equitable outcomes.

A participatory grant program can be particularly powerful when used to invest in cooperatives, which have long been a useful tool for rural communities forced to supply critical resources for themselves. Broadband internet access is and continues to be problematic for rural communities,93 but cooperatives have proven to be a useful method for investing in broadband infrastructure.94 Federal resources to support local cooperatives can help close the broadband gaps as well as gaps in other essential services throughout rural America.

Providing designated funding streams for crucial public services

In addition to a participatory grant program aimed at promoting local policy and program innovation, rural America is in desperate need of designated funding streams that provide county governments, municipalities, school districts, and other public districts with funding for crucial public services. This is critical for rural communities where local government makes up a large portion of employment, as they have seen drastic cuts to government jobs in recent years.95 Rural counties are in desperate need of financial assistance as they face an unprecedented economic downturn after years of tight budgets.96

Rural counties are frequently overlooked or excluded in the distribution of federal and state aid. While 214 metropolitan counties are guaranteed funding from the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program, an annual grant program from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to support community development initiatives, rural counties must rely on states to allocate the remaining 30 percent of CDBG funds to them.97 To make matters worse, CDBG funding has declined dramatically since 2005.98

Instead of relying on states to prioritize rural communities, the ROA should have its own CDBG equivalent that dispenses funds directly to distressed rural counties. By directing federal dollars to counties struggling to keep their services running, the ROA would fill an important gap in local budgets and rural services. Counties that contain tribal lands should be required, at a minimum, to spend the proportion of their grant equal to the native population on tribal lands and communities. These grants should be allocated based on need but would have no minimum population thresholds or matching fund requirements of any kind.99

Supporting private sector investment in rural opportunity

Private sector capital can also play a vital role in rebuilding rural economic opportunity, but markets may need more incentives to do so. Fortunately, there is a ready model for doing so in the community banks, credit unions, and loan funds that receive a special Treasury Department designation as Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) due to their demonstrated mission and commitment to serving challenged communities, including in rural America.100 CDFIs are key sources of investment in local projects and small-business creation, and by expanding the CDFI Fund, Congress can increase the capacity of these organizations to invest in small-scale programs that promote homegrown wealth creation.101 This is even more important to rural areas, which are in desperate need of capital as they attempt to transition to a greener economy. As it now stands, capital is scarce in rural America, constraining the ability of residents to make scalable local investments, ranging from clean energy transformation to affordable housing to Main Street small businesses.

To support and target additional financial investment in rural America, Congress should establish a dedicated funding stream through ROA that invests in certified CDFIs that primarily serve rural America. Such a fund would provide much-needed capital, enabling CDFI community banks, credit unions, and loan funds to accept the added risk and costs of serving hard-to-reach communities. In particular, this special rural investment fund could enable high-priority investments that would help rural communities achieve climate and environmental justice goals, including by funding community solar and updating power transmission lines.102 Funds could even potentially be available to other financial institutions, such as mission-driven credit unions, that commit to leveraging them in support of those targeted goals.

3. Strengthen rural labor markets through investment and worker protections

Much like in the case of New Deal worker protections, both urban and rural America stand to benefit from a comprehensive national labor agenda aimed at raising wages and fighting poverty. This must include a $15 an hour minimum wage, robust collective bargaining laws, strict workplace safety standards, and strong federal enforcement of labor law. Improving working conditions for rural Americans would help build local wealth and prosperity from the ground up. More than half of rural Americans live in states with a minimum wage at the federal level of $7.25 an hour.103 Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour would immediately raise the wages of 32 percent of nonmetro workers.104

But beyond raising wages, rural workers need more robust labor protections—particularly around collective bargaining, which is key to promoting economic mobility. Many rural Americans live in states with right-to-work laws that weaken the ability of workers to organize unions that can improve their working conditions. Right-to-work laws must be banned at the federal level, and Congress must pass the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would expand protections for workers organizing unions and remove barriers to formal recognition.105 In addition to problematic right-to-work laws, states often lack laws protecting the rights of public sector workers to bargain. This is crucial in the many rural counties in which the government is the largest employer. Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-HI) and Rep. Matt Cartwright (D-PA) recently introduced legislation to extend collective bargaining to public sector workers across the country.106 Moreover, agricultural workers, who largely reside in rural America, must be granted collective bargaining rights. Though New York state has recently passed legislation guaranteeing farmworkers the right to form a union, this represents only a sliver of the U.S. agricultural workforce.107

Congress can further support collective bargaining by establishing wage boards—councils of worker representatives, community organizations, and government officials that negotiate to set minimum wage and worker protection standards for a region, often on a sector-by-sector basis. For example, New York established a wage board to negotiate higher wages for fast-food workers in the state. The same can be done in any state, to the benefit of all workers. Collective bargaining in any form is key to promoting economic growth and mobility from the bottom up.108

Unfortunately, the worker protections that do exist are often underenforced; rural communities are no exception. The lack of federal enforcement particularly harms workers in states—primarily Southern states—with ineffective or nonexistent labor departments. Wage theft is prevalent and costs U.S. workers billions of dollars each year.109 Underenforcement can be especially harmful to rural workers in highly concentrated labor markets—or “modern company towns”—where a dominant employer has enhanced bargaining power over workers with few alternative employers nearby.110 This was evident during the pandemic as meatpacking plants drove the outbreak of cases in rural areas.111 Despite dangerous working conditions, workers continued to clock in at meatpacking plants in order to keep earning their paychecks and feed their families. To that end, ROA field offices should be staffed with detailees from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division and Occupational Safety and Health Administration to enhance enforcement of federal labor law in rural areas. Additional funding should be provided to these enforcement agencies given that their budgets and personnel are already stretched thin.112

Conclusion

Rural America is a frequent topic of discussion, especially during election years; but the conversation has rarely substantively addressed the problems in these communities. As previous CAP analyses have shown, rural America is a lot more diverse, vibrant, and vast than it is often portrayed.113 The three bold solutions outlined in this report would tackle the systemic issues with rural development and lead to significant structural change that can allow rural communities to thrive. Instead of taking a top-down approach, these solutions leverage the rural communities’ assets so they can thrive and prosper.

Many dismiss rural communities as a lost cause, ignoring those that are already building vibrant futures for themselves and others that are brimming with potential. Rural America was indeed left behind during the country’s recovery from the Great Recession and is now being overlooked during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, with meaningful federal partnerships and investment, the rural economy can forge a new future in which children born in wide-open spaces have the same opportunities as those raised in the suburbs—and in which people can build a life for themselves in their hometowns or in adopted tight-knit communities.

About the authors

Olugbenga Ajilore is a senior economist at the Center for American Progress.

Caius Z. Willingham is a research associate for Economic Policy at the Center.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Katharine Ferguson, David Lipsetz, Karla Thieman, Alvin Warren, Douglas O’Brien, Tony Pipa, Nathan Ohle, Shoshanah Inwood, Ashley Zuelke, and Laura Landes for their contributions to this report.

This report was made possible by Malkie Wall, Divya Vijay, Jarvis Holliday, Steve Bonitatibus, and Chester Hawkins.

Willingham previously published under the name Zoe Willingham.