Due to restrictions within the U.S. labor market, African Americans have long been excluded from opportunities for upward mobility, stuck instead in low-wage occupations that do not offer the protections of labor laws, such as those focused on collective bargaining, overtime, and the minimum wage.1 Unsurprisingly, this history of structural racism has created gaps in labor market outcomes between African Americans and whites.

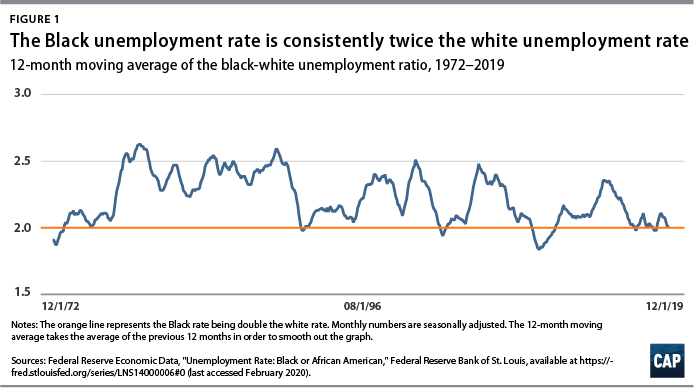

Between strides in civil rights legislation, desegregation of government, and increases in educational attainment, employment gaps should have narrowed by now, if not completely closed.2 Yet as Figure 1 shows, this has not been the case.

Since the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics started collecting data on the African American unemployment rate in January 1972, this rate has more often than not been twice as high as the white unemployment rate.3 In fact, between January 1972 and December 2019, other than during the aftermaths of recessions, the African American unemployment rate has stayed at or above twice the white rate. The only time that the African American unemployment rate was significantly less than twice the white unemployment rate was during the Great Recession. The rate dropped after the recession’s start and lasted a few months after the technical end as the white rate increased. But even when the African American rate fell below double the white rate, it never fell very far, as African Americans experienced greater amounts of layoffs. Between January 1972 and December 2019, it never reached as low as 1 1/2 times the white rate.

A recent study by the Brookings Institution found that the unemployment rate is even worse in many majority-African American metro areas.4 For example, in Washington, D.C., the African American unemployment rate is six times higher than the white rate. And a 2019 Center for American Progress issue brief highlighted the fact that unemployment gaps between African Americans and whites occur across all demographic groups.5 For example, African Americans have higher unemployment rates across all educational attainment levels and age cohorts than whites, and African Americans who are veterans have a higher unemployment rate than white veterans—though this gap is smaller.

However, focusing on unemployment rates as a measure of economic progress has its pitfalls. For instance, the unemployment rate does not measure the strength of the labor market; strength is better illustrated through the share of workers employed in the population, or the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP). This issue brief’s analysis shows that the racial gap in EPOP is narrowing, which means that the labor market is tightening and, therefore, that the racial gap in unemployment should narrow as well, since there will be a larger pool of African American workers available for existing job openings. Yet given that the racial gap in unemployment has not narrowed—but rather persists—an alternative framework is needed to explain why.

This brief provides a framework in the form of solutions to narrow unemployment gaps between African Americans and whites. These solutions do not place the burden on individuals, but rather focus on the systems preventing African Americans from fully participating in the labor market. For example, one solution is to reduce racial disparities in the criminal justice system and provide opportunities for formerly incarcerated individuals. Another is to instill workforce development programs with equity initiatives in order to address structural barriers in the labor market. Finally, policymakers need to allocate more resources toward enforcing and strengthening existing civil rights laws. The unemployment gap between African Americans and whites has persisted for nearly 50 years; policymakers need to address it before the economy can ever truly be at full employment.

Measuring the labor market gaps between African Americans and whites

When talking about unemployment rates, it is important to consider different labor market variables, as the standard unemployment rate—known as U-3—does not provide the full picture. While this standard unemployment rate reports the number of people who are actively looking for work and do not have a job, it ignores individuals who are not actively looking for work. This population of “disconnected” individuals is important to monitor, as their lack of attachment to the labor market provides important information about the economy.

In comparison, the employment-to-population ratio measures the share of the population that is employed, avoiding the issue of who is counted in the labor force since it does not exclude individuals who are not actively looking for a job. Rather, it accounts for whether people are searching for jobs and can therefore be thought of as a measure of how well people can find jobs. Another helpful labor market measure is the labor force participation rate (LFPR), which calculates the share of the total population that is in the labor force. The LFPR illustrates the extent to which people are attached to the labor market or whether they have dropped out.

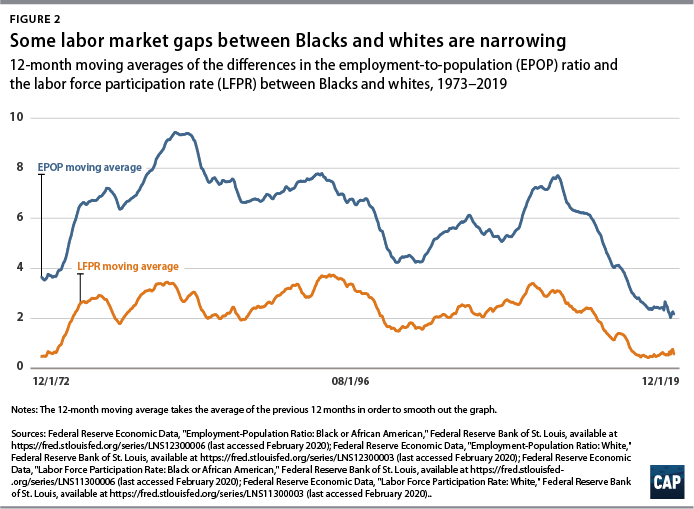

Figure 2 shows the 12-month moving averages of the differences in EPOP and LFPR between African Americans and whites, with increases indicating a widening racial gap.

The gaps in EPOP and LFPR have been falling following a post-recession peak in July 2011. While the racial gap in LFPR has nearly closed, over the past year the gap in EPOP has bottomed out at 2 percent. Given these decreases, especially with EPOP falling, it does not make sense for the unemployment rate for African Americans to continue to double the unemployment rate for whites.

One aspect that might be at issue is that EPOP and LFPR for the overall population have not fully recovered since the Great Recession. This means that not all of the individuals who dropped out of the labor force during the recession have returned. A working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research focused on the evidence for labor demand and labor supply effects, finding that imports from China and automation can explain some of the decline in EPOP on the labor demand side, while assistance programs such as Social Security Disability Insurance and Veteran Affairs Disability Compensation have had an effect, albeit smaller, on the labor supply side.6 While some have argued that the lower costs of leisure pursuits such as video games have played a part in depressing male labor force participation,7 the evidence does not support this theory—as those who exit the labor force do not have significantly stronger preferences for playing video games.8

Factors to consider to fully understand the gap

In a recent journal article, economists Ariel J. Binder and John Bound argue that in addition to automation, imports from China, and assistance programs, young men’s desire for employment has diminished due to falling marriage rates, while incarceration harms the feasibility of employment.9 These arguments are problematic, however, as they stem from a neoclassical framework that puts the onus of achieving positive outcomes on the individual and ignores structural factors—such as discrimination increasing one’s likelihood of being incarcerated—that limit the potential of individual achievement. This is particularly true for African Americans and other people of color.

A recent Federal Reserve working paper found that much of the gap in unemployment rates between African Americans and whites cannot be explained by common labor market factors such as age, education, geography, and marital status.10 The authors, however, caution against assuming that discrimination is the primary reason for the portion of the gap that is unexplained—not because it is not a factor, but rather because discrimination in many markets is likely at play in some variables already measured, including education and even marital status. For men, the Black-white unemployment gap is mostly due to high labor force exit rates for African Americans.

Mass incarceration plays a significant role in the lower labor force participation rate for African American men.11 African Americans are more likely to be incarcerated following an arrest than are white Americans, and formerly incarcerated individuals of all races experience difficulties in gaining employment.12 In spite of years of widespread agreement among researchers that incarceration is a profound factor in employment outcomes, employment statistics still do not gather data on incarceration, erasing a key structural factor.13

As discussed above, the LFPR and EPOP gaps are narrowing between African Americans and whites. Therefore, the fact that the unemployment gap persists speaks to structural barriers in the labor market that prevent African Americans from gaining employment at a rate similar to whites. Hiring discrimination is one of the primary structural barriers, as many employers exhibit and act upon biases against African Americans or other demographic groups. An extensive literature using field experiments to examine such bias finds evidence of hiring discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities.14 In addition, the mass incarceration of African Americans offers yet another example of structural barriers in the labor market.

Labor market policies need to focus on closing the unemployment gaps between whites and African Americans, rather than simply lowering unemployment. To accomplish this, solutions must focus on breaking down structural barriers.

Policy solutions

Discussions on closing unemployment gaps currently focus on the need for tight labor markets. Economists argue that as labor markets tighten, the number of people looking for jobs starts to decrease as more people become employed and, as a result, employers are forced to discriminate less to fill job openings.15 However, tightening labor markets is not a sustainable form of policy because it does not account for when the inevitable recession occurs. During a downturn, groups that have historically been excluded from labor markets tend to be the first people let go—and unemployment gaps continue to increase.16

Policymakers can take the following steps to truly address these unemployment gaps.

Institute equity initiatives as part of a workforce development strategy

More appropriate solutions focus on structural barriers rather than individual pathologies as a means to close unemployment gaps. An example of an individual pathology is the so-called skills gap, which posits that any gap in employment outcomes is due to an individual’s lack of job skills and, therefore, getting an education or completing an apprenticeship or job training program is all that is needed for employment. A recent CAP report on redesigning workforce development, however, argues that any workforce strategy that does not include equity initiatives will fail to close employment gaps.17 This is because such strategies do not account for systemic issues in the labor market that trap members of certain demographic groups in low-earning occupations or with employers who use discriminatory hiring practices.

The CAP report calls for the establishment of a national trust fund resourced through a small levy on large corporations. This fund would facilitate job training programs that are connected to high-quality jobs.18 Furthermore, an equity initiative such as a fair-chance hiring policy that includes record clearing would provide a pathway to employment for formerly incarcerated individuals.19

Reverse trends in mass incarceration

Another solution to close the gap between African Americans and whites in labor market outcomes would be to reverse the trends in mass incarceration—and to contend with the employer bias that makes it difficult for formerly incarcerated individuals to gain employment.

One such policy that would work toward this end is “ban the box,” which forbids employers from asking applicants about past involvement in the criminal justice system since employers could—and often do—use this information to discriminate against potential applicants. Thirty-five states, the District of Columbia, and more than 150 cities have implemented this policy.20 A recent Urban Institute study of early literature on ban the box found that evidence of its effectiveness is mixed but nonetheless called for policy reform beyond ban the box to tackle racial discrimination in hiring.21 The authors’ proposed reforms included expunging criminal record history, requiring “blind applications” that do not include any identifying information, and improving background check data to avoid mislabeling applicants as criminals.

Moreover, in a 2016 policy proposal for the Hamilton Project, economist Jennifer Doleac found that ban the box still leads to lower rates of hire for African Americans. Solutions outlined in her proposal included informing employers of the positive attributes of formerly incarcerated individuals and giving formerly incarcerated people the chance to acquire new skills.22

Yet while Doleac’s solutions may be helpful, they can only go so far, as they place the burden on the formerly incarcerated instead of addressing discrimination in the labor market. Policies that go further to address this structural racism—such as those outlined below—would be more effective.

Enforce employment anti-discrimination laws

Policymakers can also tackle structural racism by enforcing employment anti-discrimination laws. Vigorous enforcement of these laws was successful in closing labor market gaps during the 1970s,23 but since the 1980s, policymakers at the federal level have made a concerted effort to drain resources from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), diminishing its effectiveness. The EEOC has seen significant cuts in staff and resources since 1980.24 Increasing its budget and staff can address the commission’s large backlogs and reduce the time it takes for it to address claims.

State enforcement of anti-discrimination laws has also been lax. Many states have minimum employee thresholds that disproportionately affect African American workers; in these states, employers with fewer than 15 employees, for example, are not subject to civil rights laws and are therefore allowed to discriminate against certain groups of workers—namely, African Americans.

Other issues

This issue brief highlights important issues in racial unemployment gaps, but there are other issues that must be considered as well. Although this piece does not address gender, it is an important part of the debate. As policy experts Jocelyn Frye and Danyelle Solomon have previously written, African American women have a higher labor force participation rate than white women but are more likely to be in occupations with lower earnings.25 In addition, African American women are more likely to be breadwinners but face a higher financial burden than any other demographic group.26 Discussions of racial unemployment gaps must therefore include the gender differences within and across races to comprehensively address the issue.

Over the past four decades, women have become a larger part of the labor force yet still do not make up a significant share of higher-earning occupations.27 This leads to a second issue that future reforms must address: the earnings gap. The recovery since the Great Recession has mostly been in female-dominated occupations such as the education and health services sectors, but these occupations are generally lower paid than those dominated by men.28 However, African American men and women see the largest earnings gaps, as their earnings fall well behind those of their white counterparts and they are less likely to be in occupations with good benefits.29 In addition to unemployment gaps, policymakers must also address these earnings gaps.

Conclusion

Since the Great Recession, the U.S. economy has experienced the longest recovery on record. The primary measure of this recovery is the unemployment rate, which for African Americans has fallen from a high of 19.3 percent in March 2010 to a low of 5.1 percent in November 2019. While it is significant that unemployment for African Americans has fallen by so much, it is nonetheless concerning that the African American unemployment rate has remained twice as high as the white unemployment rate. Over the past 50 years, this has held true, showing that there are structural issues in the labor market that need to be addressed.

This brief offers two key takeaways. First, policymakers need to focus on racial gaps in the unemployment rate, rather than the unemployment level. Second, to close these gaps, policies need to focus on combating the structural barriers in the labor market. Enforcing civil rights laws, instituting equity initiatives as part of workforce development efforts, and pursuing criminal justice reform can help policymakers tackle these issues.

Policymakers should not be satisfied with a low African American unemployment rate if it continues to be twice as high as the white unemployment rate. These gaps signify structural issues in the labor market as well as lost potential output from productive workers. The solutions to close these gaps should not place the burden on these workers; instead, they need to target structural barriers preventing these workers from finding success in the labor market.

Olugbenga Ajilore is a senior economist at the Center for American Progress.