When state and local governments build large transportation infrastructure projects, they often face significant completion delays and cost overruns. One potential remedy for these issues is to use alternative forms of procurement to improve project delivery outcomes.

The most common form of infrastructure procurement is a contractual process known as design-bid-build (DBB). Under this approach, the state or local government acting as a project sponsor is responsible for planning and financing the facility as well as completing environmental review and permitting. Once financing and permits have been secured, the government typically contracts with one private firm for design and a separate private firm for construction.

Importantly, the state retains all project delivery risk under DBB, including construction delays and cost overruns stemming from unforeseen engineering setbacks, legal challenges, rising commodity prices, and inclement weather, among other factors. A central criticism of the DBB process is that private firms have no contractual or financial incentive to control costs and minimize completion delays.

A public-private partnership (P3) is an alternative form of infrastructure procurement that attempts to remedy the deficiencies of the DBB process by shifting certain risks and responsibilities from the government to the private sector concessionaire. Supporters of P3s often present risk transference as a straightforward process of negotiation between the public project sponsor and the private firm that results in a binding final contract. In exchange for taking on various types of project risk, the private firm demands a higher price—a risk premium. In theory, paying a risk premium up front is cost-effective for the public project sponsor, because it results in a fixed-price contract.

Unfortunately, this simplified and idealized version of P3s often gives way to the harsh reality of contentious litigation once large projects run into difficulties. Seemingly clear-cut contract terms become the basis for the private concessionaire’s legal claims against the state for financial compensation.

The trouble begins with contractual ambiguity. No matter how well the state negotiates its P3 deal, there will always be a basis for the private firm to claim that delays and cost overruns are the state’s fault or financial responsibility. Private claims for additional compensation often hinge on differing interpretations of individual words or phrases in the contract. Risk transference to the private sector is further undermined, since the public holds elected officials accountable at the ballot box. Public officials cannot transfer this political accountability. Moreover, mega-P3 projects are simply too big to fail, making it difficult for the government to walk away from a problematic concessionaire. These factors provide private firms with leverage when sparring with the government over delays and additional compensation.

In the end, the state may pay an initial risk premium as well as legal bills and additional compensation, which are typically agreed to as part of a negotiated settlement to avoid the uncertainty of a protracted civil trial. A deal that initially promises seamless risk transference and good value for money can become a financial albatross. The reconstruction and expansion of Interstate 4 (I-4) in Orlando, Florida—known as the I-4 Ultimate project—is a perfect example.

I-4 Ultimate project in Orlando, Florida

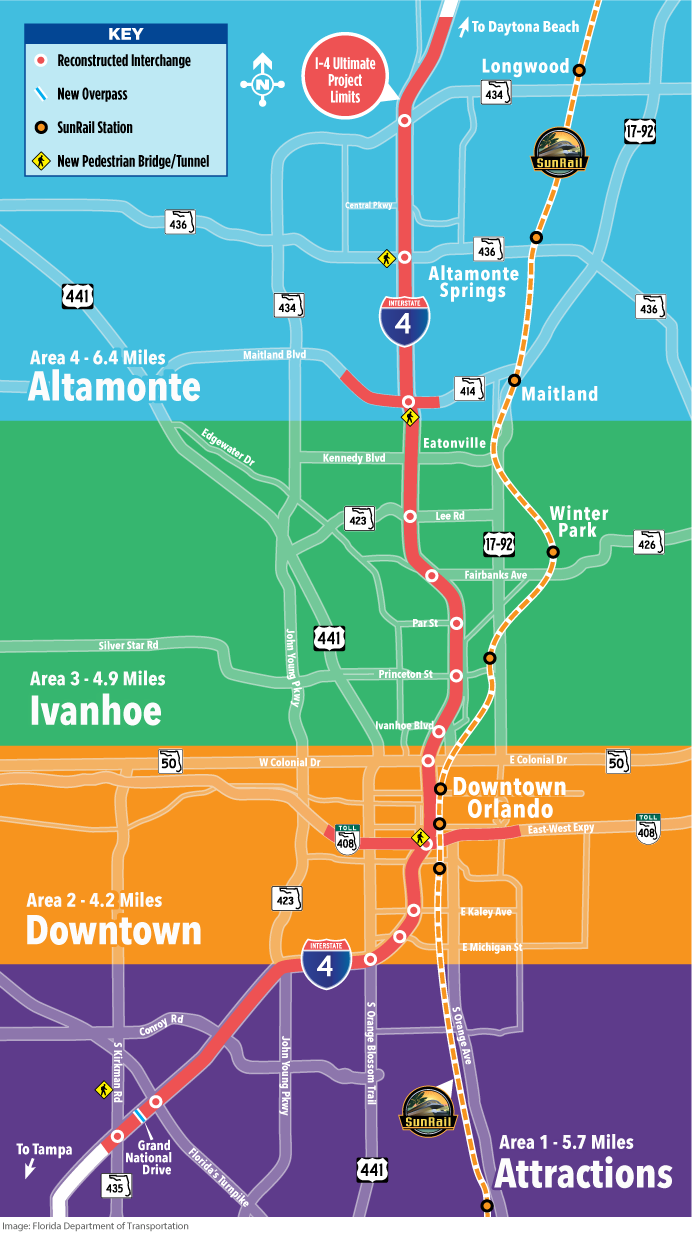

The deal requires I-4 Mobility Partners (I4MP)—the private concessionaire—to reconstruct 21 miles of I-4 through the heart of Orlando as well as add two variably priced toll lanes in each direction.1 The $2.3 billion project includes the reconstruction of 140 bridges and the reconfiguration of 15 major interchanges.2

P3s exist along a spectrum defined by the degree to which the private firm takes responsibility for and control over the project’s design, construction, financing, operations, and maintenance. The I-4 Ultimate project is a design, build, finance, operate, and maintain concession, meaning that I4MP is responsible for each of these project elements during the 40-year contract term.3 In exchange for taking on these responsibilities, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) will provide milestone payments to I4MP during the construction phase as well as ongoing payments over the remainder of the contract term. The state will retain all toll revenues from the new variably priced toll lanes.

Unfortunately, the I-4 Ultimate project is currently 245 days behind schedule, and I4MP has filed a claim against FDOT for more than $100 million to cover cost overruns.4 The justification for this claim is based on alleged delays caused by lane closure issues and construction failures.

When proponents tout the ability of P3s to transfer risk, they often leave the impression that the public project sponsor has handed off to the private partner all of its obligations and exposure to cost overruns. In reality, the government continues to hold significant liability. For instance, the I-4 concession agreement lists 24 “relief events” that could trigger a time extension or financial compensation for I4MP. Overall, the concession agreement includes the phrase “relief event” 287 times. In and of itself, this total is not meaningful, but it does highlight that the contract is replete with language detailing the numerous conditions under which the private concessionaire is entitled to time extensions and financial compensation.

The list of relief events is extensive, including everything from “Force Majeure Event,” defined as an unforeseeable and uncontrollable circumstance such as a hurricane that prevents a party from completing its contractual obligations,5 to “Discovery at, near or on the Project Right of Way of archeological, paleontological or cultural resources”6

The list also includes “FDOT-Caused Delays” and “FDOT’s failure to perform or observe any of its material covenants or obligations under the Agreement or other Contract Documents.”7 These two are particularly important, because they form the basis for part of I4MP’s claim for a completion extension and financial compensation. The concession agreement includes detailed provisions defining permissible and nonpermissible lane closures based on cause, duration, and extent. Furthermore, the agreement sets out procedures for I4MP to use when requesting lane closures as well as FDOT’s processing of those requests.

I4MP’s claim for financial compensation rests, in part, on the argument that FDOT violated the terms of the concession agreement by not approving certain lane closures that are necessary to facilitate completion of the project in a timely manner. I4MP argues that FDOT has “denied and refused to approve I4MP’s requests for necessary and critical lane closures”8 and that FDOT’s failure to “perform or observe material covenants and obligations under the Concession Agreement” has resulted in “changes to the work, and associated delays, disruption, inefficiencies, and loss of productivity.”9

In response to these claims, FDOT argues that I4MP’s closure applications often contained “unresolved Request for Information (RFI), Request for Modification (RFM) or submittals that materially affected the Released for Construction (RFC) Temporary Traffic Control Plans (TTCP) associated with the Work.” In other words, the state contends that I4MP’s lane closure submissions were frequently incomplete and either were not approved or faced delays in approval until all necessary submission materials could be reviewed.

Given I4MP’s claim that FDOT-caused delays substantially and negatively affected its ability to complete the project, it would be easy to assume that lane closures occurred infrequently. In fact, FDOT notes in its April 2017 correspondence with I4MP that the state had already approved “over 3,200 lane closure requests to date.”10 It is likely that many more closures have been approved since that time.

The potential for disputes over contract language does not end with lane closures. The I-4 concession agreement includes the phrase “commercially reasonable efforts” nine times and the word “reasonable” another 111 times.11 The word “appropriate” appears 30 times. The potential ambiguity about what constitutes reasonable effort or appropriate actions is large enough to run a highway through.

The purpose of detailing these phrases and the lane closure dispute between I4MP and FDOT is not to make claims about questions of fact or to establish liability. As of this writing, I4MP’s claim against FDOT is unresolved. Rather, the point of these details is to demonstrate that even the most comprehensive civil contract—the I-4 Ultimate contract and related technical attachments stretch well past 1,000 pages—will provide innumerable opportunities for a private concessionaire to seek financial remedy from taxpayers when problems arise and project costs escalate.

Perhaps this point is unremarkable. After all, every civil lawsuit, whether frivolous or not, must find some reason for being filed. Simply filing a suit is not a guarantee that the plaintiff will prevail. Yet, this line of argument misses that the political context around megaproject P3s tends to favor the private concessionaire.

Political accountability and value for money

Before deciding to use a P3 model to procure a transportation facility, state and local governments often undertake a value-for-money (VfM) analysis. According to the Federal Highway Administration, a VfM is used to “compare the aggregate benefits and the aggregate costs of a P3 procurement against those of the conventional public alternative.”12

P3 deals often come with a higher contract price than a traditional procurement due to the presence of private equity capital and the premium that the concessionaire charges for taking on various categories of risk. The Federal Highway Administration states, “At the core of a P3 agreement is the allocation of project risks between the public and private partners in order to minimize the overall costs of risk by improving the management of risk.” In short, the higher price tag for a P3 is justified principally by risk transference.13

But what if a P3 agreement doesn’t really transfer much risk?

In addition to the shortcomings of civil contracts, risk transference is undermined by the political accountability of elections. Government always remains the ultimate guarantor for the completion of infrastructure projects, because the ballot box holds politicians—not contractors—accountable. When officials announce a major transportation project, the public expects the government to deliver what it has promised; the method of procurement is irrelevant. The political calculation that elected officials often make is that they are better off covering a dubious cost overrun charge than facing the fallout from project failure or extended completion delay.

Once again, the I-4 Ultimate project serves as an example. Under the terms of the agreement, FDOT is able to terminate the deal if I4MP fails to carry out its obligations. Appendix 5 of the agreement sets out a system of noncompliance points that correspond to specific breaches or failures by I4MP. According to an investor outlook statement from Moody’s, FDOT assessed I4MP a total of 147 noncompliance points in May 2018.14 This total was “above the threshold for Increased Oversight per the Concession Agreement” and close to the “default threshold of 175 noncompliance points within a one year period.”15

Contract noncompliance is not the only challenge facing I4MP. According to reporting by the Orlando Sentinel, five construction workers have died on the job already, which constitutes “a grim outlier compared to other very large, contemporary road projects done by leading contractors in Florida.”16

I4MP also suffered a serious “drilled shaft failure and second drilled shaft failure in Area 2” when constructing a portion of a bridge foundation.17 Again, I4MP sought to shift the fault to FDOT, stating that the shaft failures occurred because the state “prohibited [I4MP] from using alternative foundation methods, such as driven piles, which would not have resulted in the same problem.”18

In response to these extensive safety and construction issues, I4MP argues that it is entitled to more than $100 million in additional compensation. For each line item of the claim, I4MP references a section of the concession agreement that it interprets as supporting its argument for additional compensation. Specifically, I4MP argues that it is entitled to “additional compensation for Extra Work and Delays, including without limitation, additional labor and indirect costs and expenses” as well as compensation for delayed construction payments and a delay in the final acceptance payment due upon substantial completion of the project.19

A high worker fatality rate and major delays due to construction failures are exactly the types of problems that should theoretically trigger contract termination. Yet, FDOT has not attempted to terminate its agreement with I4MP. This raises two related questions. First, what would it take for FDOT to terminate the concession agreement? Clearly, terminating the concession agreement would cause political upheaval, further completion delays, and major litigation, among other unpleasant outcomes. Moreover, finding a replacement firm for I4MP could prove problematic, as potential competitors might stay away from a project facing such intense challenges and uncertainty.

This leads to the second question: Is the I-4 Ultimate project simply too big to fail? In the world of finance, a bank or other financial institution is considered to be too big to fail—or systemically important—when its collapse would trigger a larger financial and economic crisis.20 I-4 in Orlando represents the infrastructure corollary to this finance concept, making it difficult to envision how FDOT could terminate the deal without risking a deepening of the challenges facing a systemically important highway project. This political context buttresses I4MP’s ability to push its claim for compensation and undermines FDOT’s ability to truly transfer risk via the P3 contract.

Conclusion

The central purpose of a P3 contract is to transfer construction risk from the state to the concessionaire. However, the political pressure to complete major transportation projects combined with the inherent weaknesses of civil contracts means that the state is able to transfer only a modest amount of project risk. As a result, public project sponsors should adjust their VfM analyses to reduce the threshold value at which a P3 project is considered cost-ineffective. In short, public project sponsors should not accept a substantial risk premium, since less risk is actually transferred than is commonly assumed in both the public discourse around P3s and in project-specific VfM analyses.

Kevin DeGood is the director of Infrastructure Policy at the Center for American Progress.